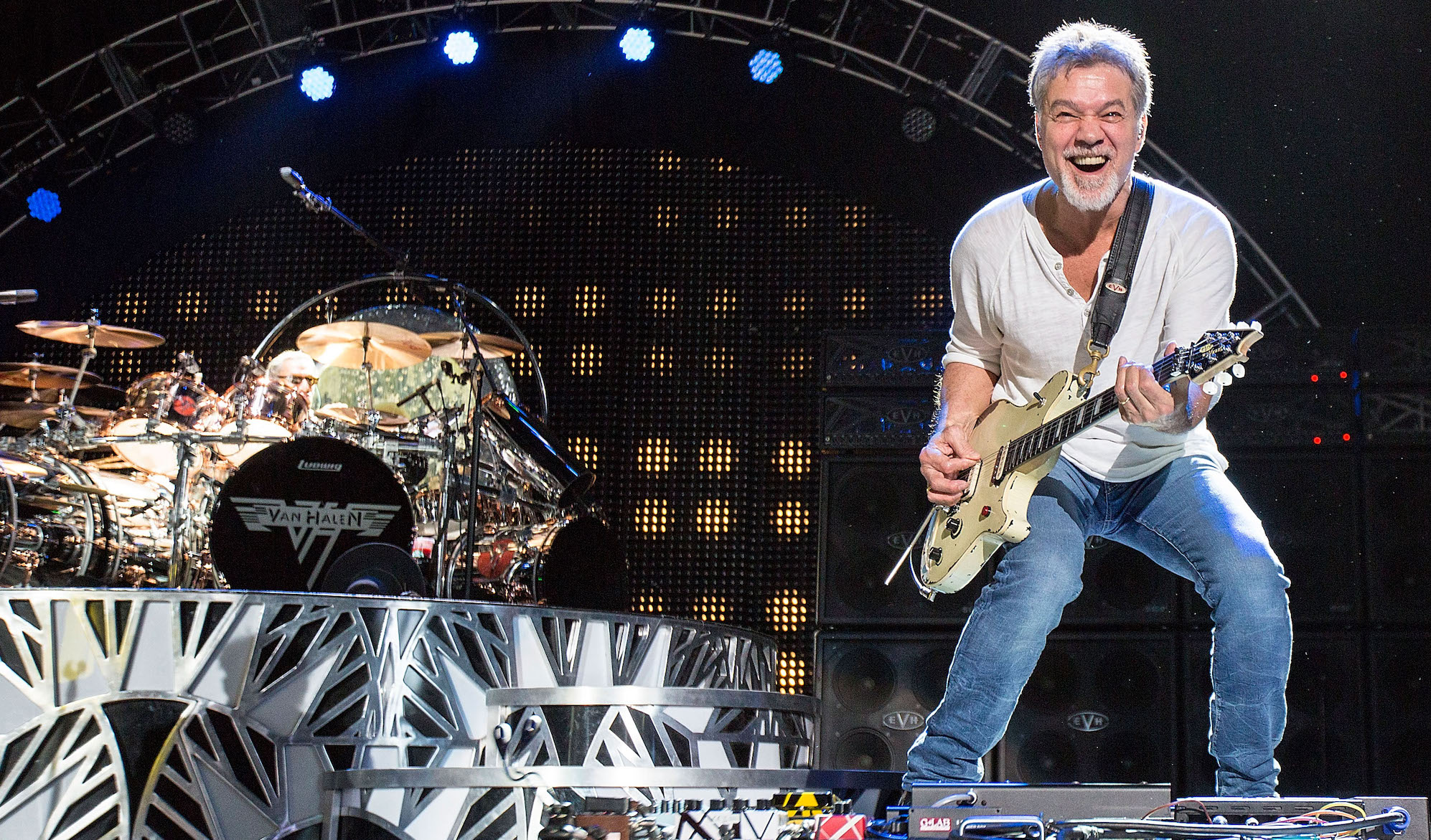

Eddie Van Halen revisits Van Halen's landmark '1984' album

EVH tells GW how Van Halen's Diamond-certified blockbuster came to be

This story originally appeared in the February 2014 issue of Guitar World.

When rock music fans first heard Eddie Van Halen’s radical, innovative tapping technique at the end of Eruption, many mistakenly thought that they were hearing a synthesizer.

Six years later when Van Halen released their 1984 album, there was absolutely no doubt that a synthesizer was generating the majestic and mysterious sounds that they heard this time around. In fact, the first note of Eddie’s guitar wasn’t heard until two minutes and 10 seconds into the album’s first two songs.

With the album’s initial single Jump, Ed proved that he could play keyboards every bit as well as he could play guitar, but even more importantly he also showed the world that he could craft a pop song that was as good as, if not better than, anything else out there at the time.

Van Halen’s use of a synth on Jump ushered in a new era of appreciation for the instrument, which previously was associated mostly with new wave bands and electro pioneers like Kraftwerk, Gary Numan and Tangerine Dream.

Almost overnight, sales of synthesizers increased exponentially, similar to the revolutionary boost in guitar sales that Van Halen influenced after the first Van Halen album made its debut, and fortuitously coinciding with the introduction of the first affordably priced polyphonic synths.

Music store keyboard departments were soon filled with the sounds of aspiring musicians playing ham-fisted versions of Jump, much the same way that guitar departments were subjected to novices attempting to play Stairway to Heaven.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

But there is much more to 1984 than Jump, which incidentally was Van Halen’s first and only song to reach the Number One spot on the Billboard Hot 100 singles chart. While three of the album’s nine songs are dominated by synths, the entire album features some of Eddie Van Halen’s hottest and most impressive guitar playing ever.

The pumping groove of Panama and the heavy-hitting House of Pain rocked as hard as anything the band had offered on its five previous albums, while Top Jimmy and Drop Dead Legs introduced entirely new territory that paved the way for the band’s next chapter.

Ed’s dazzling guitar solos even elevated the keyboard-dominated songs Jump and I’ll Wait. The showstoppers from a guitar perspective are Hot for Teacher, with its hot-rodded blues boogie shuffle, and Girl Gone Bad, featuring Van Halen’s signature harmonics, a dynamic progressive rock structure and a blazing solo filled with Allan Holdsworth–style legato runs.

The fact that every song on the album was as strong as anything else in Van Halen’s catalog up to that point in time is also impressive. In total, the album delivered four singles – Jump, I’ll Wait, Panama and Hot for Teacher – which all remain staples of classic-rock radio today.

1984 went on to become one of Van Halen’s all-time best-selling albums, matched only by their debut album, which also sold more than 10 million copies in the U.S. alone.

1984 is further notable for being one of the best-selling hard rock albums of all time, sharing lofty heights with company like AC/DC, Def Leppard, Guns N’ Roses, Led Zeppelin and Metallica.

But perhaps the most noteworthy attribute of 1984 is that it is likely the only Diamond-certified (sales of 10 million or more) album that was recorded entirely in a home studio. [Boston’s debut album is a close contender, but one of its songs was recorded in a pro studio.]

Of course, the facility now known as 5150 Studios is not the ordinary home studio. From the very beginning, 5150 was a fully professional facility, starting off as a 16-track studio equipped with classic gear that, while it seemed outdated during its time of installation in 5150, was more than up to the task of capturing Ed’s ideas in a polished, finished state that was suitable for release.

1984 was the first album to come from 5150 Studios, and the studio has remained Van Halen’s home base for all of the albums the band has recorded since then. The studio was built during a particularly fertile period of creativity for Ed that was also marked by his desire to protect his creative vision and oversight of how Van Halen’s records should be made.

Fortunately, engineer Donn Landee, who had recorded all of Van Halen’s previous five albums, saw eye to eye with Ed’s thinking and played an instrumental role both in building 5150 Studios and recording the 1984 album.

Landee even came up with the studio’s name, adopting 5150 from the California Welfare and Institutions Code for involuntary confinement of a mentally instable person deemed to be a danger to themselves and/or others.

Donn overheard the code number one night while listening to police broadcasts on a scanner, and Ed and Donn jokingly called themselves “5150s” after many around them said that they were crazy to build their own studio. Both agreed that 5150 was the perfect name for their new “asylum.”

Although Ed has never recorded a solo album and apparently never plans to, 1984 may very well be the closest thing to a Van Halen solo album that the world will ever get, as the record is overflowing with his creative input and inspiration.

While 1984 is still a band record, distinguished particularly by Alex Van Halen’s powerful drumming and David Lee Roth’s street-poet lyrics and inimitable vocals, it also offers one of the most pure visions of Ed’s musical talents and breadth that he’s ever produced.

1984 may have been released 30 years ago, but Ed Van Halen still fondly remembers many fine details of the album’s creation. The fact that Ed was able to complete this achievement during a tumultuous period that ultimately led to the band’s initial lineup breaking apart is somewhat miraculous, eclipsed only by the album’s phenomenal success.

What inspired you to build your own studio at your home?

I used to have a back room in my house where I set up a little studio with a Tascam four-track recorder to demo songs. I really wanted to record demos that sounded more professional than what I was doing.

I used to spend so much time getting sounds and writing. I have a tape of me playing in the living room at five A.M., and you can hear Valerie [Bertinelli, Ed’s ex-wife] come in and yell that she’s heard enough of that song. That was another reason why I built the studio.

The bottom line is that I wanted more control. I was always butting heads with [producer] Ted Templeman about what makes a good record. My philosophy has always been that I would rather bomb with my own music than make it with other people’s music. Ted felt that if you re-do a proven hit, you’re already halfway there.

I didn’t want to be halfway there with someone else’s stuff. Diver Down was a turning point for me, because half of it was cover tunes. I was working on a great song with this Minimoog riff that ended up being used on Dancing in the Street.

It was going to be a completely different song. I envisioned it being more like a Peter Gabriel song instead of what it turned out to be, but when Ted heard it he decided it would be great for Dancing in the Street.

Fair Warning’s lack of commercial success prompted Diver Down. To me, Fair Warning is more true to what I am and what I believe Van Halen is. We’re a hard rock band, and we were an album band. We were lucky to enter the charts anywhere.

Ted and Warner Bros. wanted singles, but there were no singles on Fair Warning. The album wasn’t a commercial flop, but it wasn’t exactly a commercial success either, although for many guitarists and Van Halen fans, Fair Warning is a hot second between either Van Halen or 1984.

The album was full of things that I wanted, from Unchained to silly things like Sunday Afternoon in the Park. I like odd things. I was not a pop guy, even though I have a good sense of how to write a pop song.

How did 5150 go from being just a demo studio to a fully equipped pro facility?

When we started work on 1984, I wanted to show Ted that we could make a great record without any cover tunes and do it our way. Donn and I proceeded to figure out how to build a recording studio. I did not initially set out to build a full-blown studio. I just wanted a better place to put my music together so I could show it to the guys. I never imagined that it would turn into what it did until we started building it.

Back then, zoning laws disallowed building a home studio on your property. I suggested that we submit plans for a racquetball court. When the city inspector came up here, he was looking at things and going, “Let’s see here. Two-foot-thick cinder blocks, concrete-filled, rebar-reinforced… Why so over the top for a racquetball court?” I told him, “Well, when we play, we play hard. We want to keep it quiet and not piss off the neighbors.” We got it approved.

Donn was involved with the design. I certainly didn’t know how to build a studio. It was all Donn’s magic. We built a main room and a separate control room. When we needed to find a console, Donn said that United Western Studios had a Bill Putnam–designed Universal Audio console that we could buy that he was familiar with.

We went to take a look at it, and it was this old, dilapidated piece of shit that looked like it was ready to go into the trash. Donn said, “Let’s buy it,” and I was going, “What the hell are you thinking?”

He said that he could make it work, so we paid $6,000 for it and lugged it up here. He rewired the whole console himself using a punch-down tool. Donn used to work for the phone company, so he was an expert at wiring things.

We also needed a tape machine, so we bought a 3M 16-track. Slowly, the studio turned into a lot more than I originally envisioned. Everybody else was even more surprised than I was, especially Ted. Everybody thought I was just building a little demo room. Then Donn said, “No man! We’re going to make records up here!” When Ted and everybody else heard that, they weren’t happy.

It sounds like Donn wanted as much creative freedom as you did.

Oh, definitely. We had grown really close and had a common vision. Everybody was afraid that Donn and I were taking control. Well…yes! That’s exactly what we did, and the results proved that we weren’t idiots.

When you’re making a record, you never know if the public is going to accept it, but we lucked out and succeeded at exactly what my goal was. I just didn’t want to do things the way Ted wanted us to do them. I’m not knocking Diver Down. It’s a good record, but it wasn’t the record I wanted to do at the time. 1984 was me showing Ted how you really make a Van Halen record.

You really were overflowing with creativity during the period between Diver Down and the middle of 1984. During that time you also recorded Beat It with Michael Jackson, the Star Fleet Project with Brian May, The Seduction of Gina and The Wild Life soundtracks, and you and Donn produced a single for Dweezil Zappa.

I had a lot of music lying around, because all I did was write. I remember, we were rehearsing for the Diver Down tour at Zoetrope Studios when Frank Zappa called me and asked if I would produce a single for his son Dweezil.

I also did the Brian May Star Fleet Project then and the session with Michael Jackson. Val asked me to write some music for a TV movie she was doing. Until you mentioned it, I had forgotten that I had recorded the Wild Life soundtrack back then.

Now I remember that Donn wasn’t very happy, because he had to mix it on his own. I had to leave to go on the tour that we were doing with AC/DC in Europe that summer.

We also did the US Festival in the middle of recording the 1984 album, and before that we toured the U.S., Canada and South America and played about 120 shows. And I also had to build the studio during that period too! I don’t know how I pulled all of that off.

The US Festival proved that Van Halen were the biggest band in the world at the time.

What’s funny is that we made the Guinness Book of World Records for making $1.5 million for that one show. I remember hearing a DJ on the radio saying that we made so much money per second. What he didn’t realize is that we put every penny of that into the production. We didn’t make a fucking dime when it was all over.

You also spent about a month just preparing for that one show.

There was so much going on. We did that in the middle of making a record and I was doing all of this outside stuff. Then again, the Michael Jackson session only took 20 minutes, so it wasn’t like all of these things were taking that much time.

What is the first song you recorded at the studio?

That was Jump. Once Ted heard that song, he was full-hog in. He said, “That’s great! Let’s go to work.” When I first played Jump for the band, nobody wanted to have anything to do with it. Dave said that I was a guitar hero and I shouldn’t be playing keyboards. My response was if I want to play a tuba or Bavarian cheese whistle, I will do it.

As soon as Ted was onboard with Jump and said that it was a stone-cold hit, everyone started to like it more. But Ted really only cared about Jump. He didn’t care much about the rest of the record. He just wanted that one hit.

Alex was very supportive of everything we were doing. He wasn’t happy with his drum sound, especially on the first and second records. There was only one room at 5150 at the time, so we were very restricted. Recording drums there was a challenge. It really was a racquetball court, where one third of the space was the control room and the rest was the main room.

Because the space was so limited, Alex had to use a Simmons kit except for the snare. We all played at the same time. I had my old faithful Marshall head and bare wooden 4x12 cabinet facing off into a corner and Al was in the other corner.

We set up some baffles to have isolation between my guitar and the drums. I would sit right in front of my brother and play without headphones. All I needed to hear was his drums. There were a lot of limitations.

You wouldn’t know it though when you listen to the end product. The sounds on that record are impressive.

I have to give all of the credit to Donn. His approach to everything was genius. I used the same Marshall amp to record the first six Van Halen albums, but my guitar sound on each album is different. The drum sounds are different too. That was all Donn. He is a man-child genius on the borderline of insanity.

He would wear what looked like the same pants, shirt, socks and shoes every day of his life. Then you go to his house and see that he has a closet full of all the same type of clothes. He’s just like Einstein.

Alex and Donn got a lot closer on 1984 as well. Drop Dead Legs and I’ll Wait were more towards Al’s liking, as opposed to the first record. I remember when Al and I went to Warner Bros. to pick up the cassettes of the very first 25-song demo tape we did for them in 1977.

We popped it into the player in my van and expected to hear Led Zeppelin coming out, but we were kind of appalled by what we heard. It just didn’t sound the way we wanted it to sound. The first album sounds a little better, but it still wasn’t the way we imagined it should sound. It’s very unique sounding. I wouldn’t even know how to duplicate it, to tell you the truth.

Don’t ever venture into an amp or guitar forum. You’ll see page after page of arguments by people who still can’t figure it out either.

The overall guitar sound on the first record isn’t that difficult to duplicate, but the overall package of how the whole band sounded was not what Alex and I expected it would be. There is so much EMT plate reverb on it, which is something I never had really heard before.

It still holds up today to a certain extent. It’s not in your face or all that heavy, but the songs are great. If you heard us live, we sounded different. We were much heavier, and that’s what Alex and I expected to hear on the record.

1984 not only sounds different than Van Halen’s previous records but each song also sounds different than each of the other songs on the album.

Someone played me his new record once, and every song on it was the same beat. Most of the songs were even in the same key. You could barely distinguish between the songs. He said, “Once you’ve got them, you don’t want to lose them.” That was so opposite of the way I think.

I like to listen to records that go through changes and take you for a ride. I like things that come out of left field and keep your interest, where each song holds up individually and together they make a well-rounded collection. I prefer to make records that you listen to from beginning to end. I’m really not into recording just singles.

And then you recorded Jump, which became the band’s biggest single ever – even bigger than any of the cover songs Van Halen ever recorded.

Jump was the only Number One single we ever had. Outside of Jump, most of the other material was already written when we started to record the album.

For the first six records and tours, we all traveled together on the same bus, which Dave called the disco sub. All I did was write. You can hear the bus generator on all of the demo tapes I recorded.

I wrote Jump on a Sequential Circuits Prophet-10 in my bedroom while the studio was being built. Everytime I got the sound that I wanted on the right-hand split section of the keyboard, it would start smoking and pop a fuse. I got another one and the same thing happened. A guy I knew said I should try an Oberheim OB-Xa, so I bought one of those and got the sound I wanted.

I always carried a microcassette recorder with me. I recorded my idea for Girl Gone Bad by humming and whistling into it in the closet of a hotel room while Valerie was sleeping. I pretty much wrote the entire song in that state, and then when I got home I put it all together.

When the guys once asked me to write something with an AC/DC beat, that ended up being Panama. It really doesn’t sound that much like AC/DC, but that was my interpretation of it.

For Top Jimmy I had a melody in my head and I tuned the guitar to that melody. Steve Ripley had sent me one of his stereo guitars that had 90 million knobs and switches on it. That was too much for me to comprehend, so I asked him for a simpler version. He sent me one with a humbucker in the bridge and two single-coils at the middle and neck positions. It was just a prototype.

For some strange reason I picked up that guitar, tuned it to Top Jimmy, and that’s what I ended up using, because it sounded interesting. That rhythm lick I play after the harmonics sounds cool ping-ponging back and forth. You can’t really hear it unless you’re wearing headphones. It just fit the track.

Drop Dead Legs is one of the most unique songs on the album.

That was inspired by AC/DC’s Back in Black. I was grooving on that beat, although I think that Drop Dead Legs is slower. Whatever I listen to somehow is filtered through me and comes out differently. Drop Dead Legs is almost a jazz version of Back in Black. The descending progression is similar, but I put a lot more notes in there.

The solos almost always go into a different place than the rest of the song. Sometimes you even change keys, like on Jump, Top Jimmy and Panama.

I view solos as a song within a song. From day one that is just the way that I write things. I always start with some intro or theme and establish a riff, then after the solo there’s some kind of breakdown section. That’s there in almost every song, or else it returns to the intro.

What inspired you to record actual engine growls from your Lamborghini on Panama?

Having the studio here gave Donn and I the luxury and freedom to do all kinds of things. They thought we were nuts to pull up my Lamborghini to the studio and mic it. We drove it around the city, and I revved the engine up to 80,000 rpm just to get the right sound.

We’ve done all kinds of silly things up here. One time a septic tank needed to be removed. Donn lowered a mic into it, and we threw an Electrolux vacuum in there. We called it Stereo Septic. I have a tape of it around here somewhere, although I’ve never used it on anything. It’s fucking hilarious.

I basically lived in the studio back then. If Valerie ever needed to find me, she just had to look in the studio, because I was always there. Even when we weren’t recording music for the band, Donn and I would be in there every day, putzing around, making noise, coming up with riffs, playing piano, or doing whatever.

It was a bummer when we stopped working together. Donn just totally left the music business. I went to his house once and asked him to reconsider. He said, “Nah. I probably wouldn’t even remember how to do it.” I said, “That’s bullshit. Everything we did we didn’t know what the fuck we were doing anyway!” We were just experimenting and having fun all the time.

It sounds like everyone was having fun on Hot for Teacher.

I’m a shuffle guy. I love fast shuffles. I think that stems from my dad’s big-band days. Every Van Halen record has a song like that – I’m the One, Sinner’s Swing. It was an extension of that – more of me!

I distinctly remember sitting in front of Al on a wooden stool and playing that part during my solo where it climbs. Well, I can’t count, so Al needs to follow me. I’d sit right in front of him, and then he’d look at me like, “Now!”

Al’s drums on the intro sound like a dragster warming up before a race.

When he started putzing around with that, we were going, “Holy shit!” It really does sound like a hot rod or dragster. You can only pull that off with Simmons drums because they sound so unique. Regular drums don’t sound the same.

There’s something to be said about the years that we used Simmons. The only bad part was how those drums affected Al’s wrists. When you hit those things there’s no bounce or give. It’s like pounding concrete, and thanks to the amounts of Schlitz malt liquor we drank, we hit everything twice as hard. Al would hit them with sticks that were like baseball bats.

That first drum fill on I’ll Wait right before the vocals was an accident. It’s one of my favorite parts of the song. Al hit the hi-hat instead of the cymbal. The only way we could record in that room was to have Al play just the drums and then later overdub the cymbals. He just forgot to hit the cymbal. It reminds me of Ginger Baker on White Room where Ginger does a similar thing on the first verse.

You've said that I’ll Wait got the most resistance from others.

Ted hated that song. When I played it for him, he kept humming Hold Your Head Up by Argent just to piss me off. It doesn’t sound anything like that.

House of Pain originally dates back to the demos you recorded with Gene Simmons and the Warner Bros. demos, but the version on 1984 is different. How did it finally make the cut six albums later?

The only thing that’s the same is the main riff. The intro and verses are different, I guess because nobody really liked it the way that it originally was.

You also mixed the album at 5150. Was that a challenge?

The funniest story about the whole record was near the end, when Donn and I were mixing it. Ted seemed to think that we were already done, and we had a deadline to meet.

The original plan was to release the album on New Year’s Eve of 1984, but Donn and I weren’t happy with everything on it. Donn and I would be in there mixing and the phone would ring. It would be Ted at the front gate to my house, wanting to come in.

To this day, I don’t think that Ted knows what actually went on. My whole driveway is like a big circle. So Donn would grab the master tapes, put them in his car, go out the back gate, and wait as Ted was coming through the front gate because Ted wanted the tapes. He’d ask where Donn and the tapes were, and I’d say that I had no idea.

This went on for about two weeks. Little did he know that Donn was sitting outside the back gate, waiting for him to leave. We had walkie-talkies and I would tell Donn when Ted was leaving. Then Donn would drive down the hill and come back in through the front gate, and Ted never saw him as he was going out behind him. It was a circus!

Nobody was happy with Donn and me. They thought we were crazy and out of our minds. Ted thought that Donn had lost it and was going to threaten to burn the tapes. That was all BS. We just wanted an extra week to make sure that we were happy with everything.

Ted just didn’t see eye to eye with the way I looked at things. That was my whole premise for building the studio. I wanted to make a complete record from end to end, not just one hit. As soon as “Jump” was done, he looked at the rest of the album as filler. It wasn’t that to me. It’s a good record because it was different.

It’s ironic that the only thing that kept 1984 out of the Number One spot on the Billboard 200 albums chart was Michael Jackson’s Thriller, which you also played on.

We had the Number One single, but he had the Number One album. Of course everyone blamed me. They said, “If you hadn’t played on ‘Beat It’ that album wouldn’t be Number One.” We’ll never really know who helped who more. I do know that when I played on his record, it helped expose Van Halen to a different audience.

Some of the best-selling rock albums of all time never made it to Number One on the charts, like AC/DC’s Back in Black, Led Zeppelin IV and Boston’s debut album. Peak chart positions aren’t always an indicator of success.

We were projected to go to Number One the week when Michael Jackson was filming that Pepsi commercial and burned his hair [on January 27, 1984]. Then that happened. Everyone was going, “Oh, Michael burned his hair! We’d better go buy his record.”

A similar thing happened with [Van Halen’s 2012 album] A Different Kind of Truth. It was supposed to debut at Number One, but it was released the same week as the Grammys when Adele won a bunch of awards, which suddenly spiked her album’s sales.

I knew that was going to happen. We sold close to 200,000 records, which would have made the album number one almost any other week of the year. But being number one doesn’t really mean jack fuck all. We sold twice as many records as other records that year that landed in the Number One position. 1984 and Van Halen are among a very small group of albums that have won RIAA diamond certification for selling more than 10 million copies. Neither one of those records ever went to Number One.

The 1984 tour was also one of the band’s biggest tours ever.

Our live show for the 1984 tour just could not get any bigger, but it was so over the top that we never made any money from it. We had 18 trucks hauling the stage and equipment. That was unheard of. The standard lighting rig had 500 to 700 lights, and we had over 2,000.

We could never have topped that. We had the banners with the Western Exterminator guy on them [an illustrated character with a top hat, sunglasses and a large hammer, used in the company’s marketing]. We filled the entire place with equipment and lights. Great memories.

Was the Frankenstein still your main guitar in the studio on that album?

I had actually retired the Frankenstein by then. I’m pretty sure I used the Kramer 5150 guitar the most on that album – Panama, Girl Gone Bad, House of Pain, the solos on Jump and I’ll Wait.

You used a ’58 Gibson Flying V on several songs as well, particularly Hot for Teacher and Drop Dead Legs.

You are very right. The ride out lick that I play on the last minute and a half of Drop Dead Legs came afterward. We had already finished recording the song, and then I came up with that part, which I thought would sound great at the end of the song.

I’m not sure how Donn put it together, but we recorded it separately and added it to end of the song, even though it sounds like it was recorded at the same time. That ride out solo was very much inspired by Allan Holdsworth. I was playing whatever I wanted like jazz – a bunch of wrong notes here and there – but it seemed to work.

Your solos on the entire record are some of your most innovative playing ever. You really were going outside of your comfort zone and playing new, unusual lines, especially on your solo to Girl Gone Bad.

Allan really inspired me. There weren’t any other guitarists out there who were blowing my mind at the time other than him. I don’t think anyone can copy what he does. He can do with one hand what I need two to do. How he does it is beyond me. But sometimes his playing is so out there that people don’t get it.

I got Allan a record deal with Warner Bros., and I was supposed to co-produce the album with him, but he wouldn’t wait two or three weeks for me to get back from tour in South America, so he did it himself. I really wish that he would have waited. I believe I could have helped him a lot.

He had this one riff on his demos that I heard completely different than how it ended up on his record. That lick could have been a monstrous Zeppelin-style riff, but instead it turned into a lounge song.

I feel bad for Allan because the album could have really been something good for him. I did everything I could to help him. It wasn’t his only shot, but it was a hell of a shot. If he only would have waited a few weeks, things could have turned out very different.

What is creating the chorus-like sound on the intro to Drop Dead Legs?

I really don’t remember. That was all Donn, although Donn never added any flanging or phasing to my guitar. I think I may have used a little MXR Phase 90 on that. I played through the Eventide Harmonizer all the time back then, but I used it mostly to split my guitar signal so it came out of both sides.

Back then I didn’t play in the control room – I was always out in the main room – so I never really knew what Donn was doing while I was recording tracks. I wouldn’t hear it until we were done playing, and I usually liked what I heard.

Your tone got drier on each successive album. On 1984, I really only hear reverb on House of Pain, Panama and parts of Girl Gone Bad.

That came from my dislike of that EMT plate reverb that our first album is bathed in. It had its time and place, but it strikes a bad nerve with my brother and me.

You didn’t get caught up in all of the production gimmicks that were prevalent during that period in the Eighties. As a result 1984 doesn’t sound dated like most other albums that came out back then.

I’ve never been in touch with what is going on in the world because I rarely ever listen to anything else. I think that the record did well because it was ahead of its time and it was simply different. It was even different for Van Halen, particularly because it had two keyboard songs on it. Having built 5150, it was a very special time in my life, and that shows in the music.

Chris is the co-author of Eruption - Conversations with Eddie Van Halen. He is a 40-year music industry veteran who started at Boardwalk Entertainment (Joan Jett, Night Ranger) and Roland US before becoming a guitar journalist in 1991. He has interviewed more than 600 artists, written more than 1,400 product reviews and contributed to Jeff Beck’s Beck 01: Hot Rods and Rock & Roll and Eric Clapton’s Six String Stories.