'Imagine' This: How John Lennon and George Harrison Teamed Up to Record a Classic Album in 1971

“I think my greatest pleasure is writing a song — words and lyrics — that will last longer than a couple of years.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

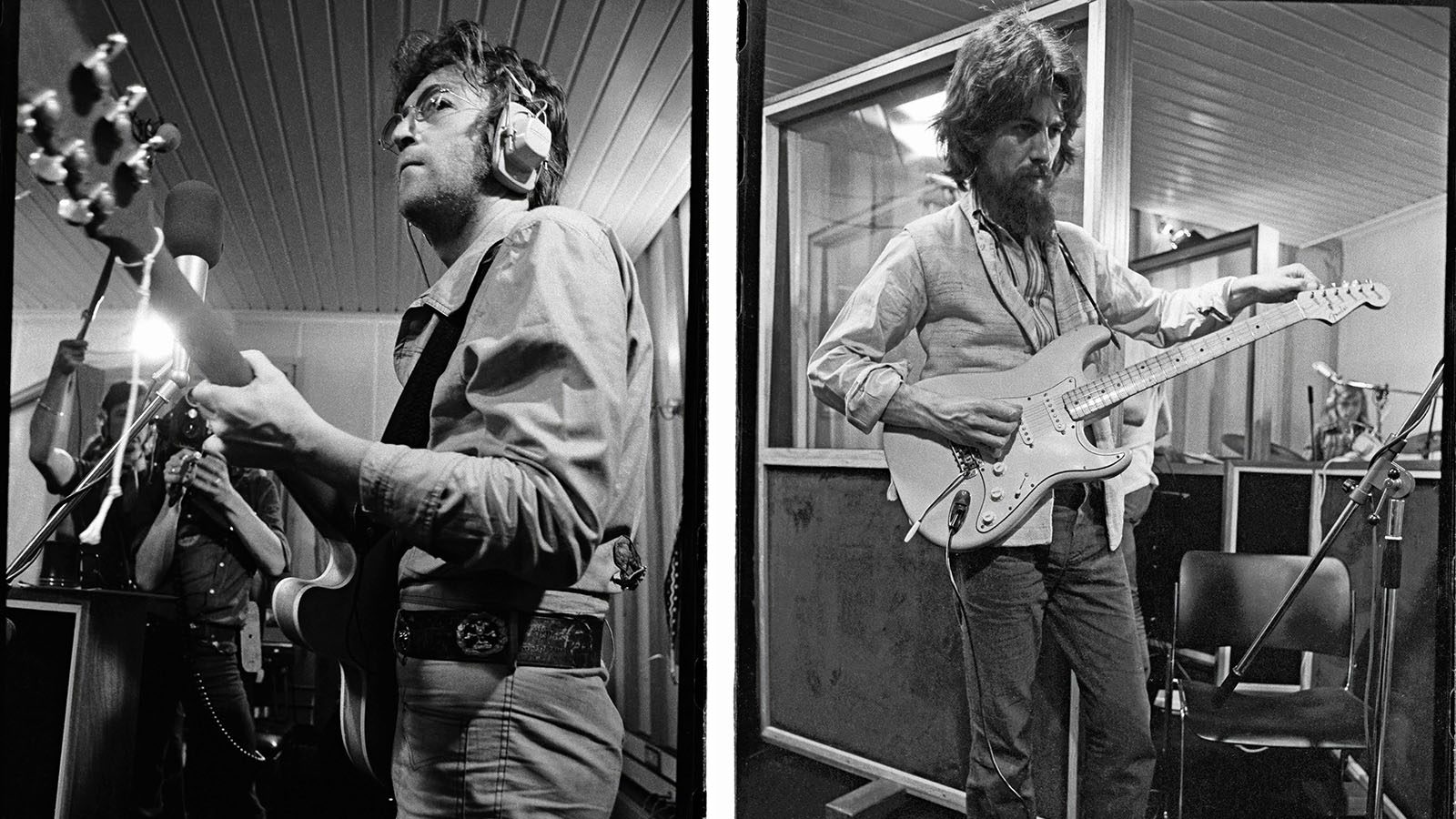

In the wintry early months of 1971, John Lennon embarked on a recording project that would prove to be momentous in its influence on rock music and the world at large. The album’s title track is still sung today at protest marches, sporting events, pop concerts, prayer vigils and anywhere else people gather in unity. It will most likely still be sung and treasured for many years to come.

The Imagine album ranks high among Lennon’s towering musical achievements, both as a solo artist and with the Beatles. At turns brutally honest and achingly intimate, the record opened up new vistas of expressiveness for songwriters and creative artists in every medium.

But Imagine isn’t usually regarded as much of a guitar album. Because the disc’s piano-driven title track has become a timeless international peace anthem, it tends to loom larger in the public consciousness than the rest of the disc. Which is a bit of a shame, as “Imagine” is only one of several album tracks that find Lennon at the top of his game as a songwriter. From “Jealous Guy” to “How Do You Sleep?,” the disc reflects Lennon at his most vulnerable and his most vicious. It also contains some iconic guitar moments that team Lennon with his Beatles co-guitarist George Harrison. With deep shared roots but very disparate, distinctive styles, the two rock guitar icons mesh magically on tracks that encompass influences ranging from folk and blues to all-out rock.

“George Harrison’s guitar playing was more classically beautiful,” Yoko Ono told me in 1998. “But John’s was restless — beautiful, restless stuff.”

The late-2018 release of Sony Music’s six-disc box set, John Lennon — Imagine: The Ultimate Collection, sheds fresh light on this landmark album, with a wealth of outtakes, isolated tracks, raw mixes and multi-format remixes that reveal new layers of sonic subtlety. Also newly reissued, on restored, remastered DVDs from Eagle Vision, are two seminal films associated with the Imagine album. Gimme Some Truth is a “making of” documentary that takes us inside the studio with Lennon as he records the album. And Imagine is the innovative 1972 film that John and Yoko made based on the songs from Imagine and several from Ono’s 1971 album, Fly. This film was the first “album for the eyes” and an important music video precursor. Taken all together, these reissues provide an intimate look at one of the world’s most influential musical artists during one of his most fertile and creative periods.

Imagine was an album made for rapidly changing times by a man whose own life was going through a similarly turbulent personal transition. The Sixties were over. The Beatles were over. Lennon’s first marriage was over, and he’d embarked on a romantic, spiritual and creative partnership with multi-media artist Yoko Ono. For the first time since his teens, Lennon was outside the Beatle bubble, and it was a bit scary for him.

He’d boldly confronted several of his deepest-seated psychological issues on his raw-boned, 1970 debut solo album, John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band. That disc had been the outcome of the Primal Scream therapy that John and Yoko underwent in 1970 with American psychologist Arthur Janov. During that period in which he was vividly reliving some of the most traumatic moments in his life, Lennon, according to Ono, “was always holding onto the guitar as a security blanket.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Having exorcised a few personal demons and established a powerful voice as a solo artist with the Plastic Ono Band disc, Lennon had a more expansive, multifaceted sound in mind for Imagine. Comparing the songs on Imagine with those on the Plastic Ono Band album, Lennon said, “There are a lot of delicate things happening inside them musically that didn’t happen so much in the last one.”

As part of the wider palette Lennon had in mind, he recruited his former Beatles co-guitarist, George Harrison, to play on five of the album’s 10 tracks. Harrison’s heavily bearded visage was one of several familiar faces inside Lennon’s studio, Ascot Sound, at Tittenhurst Park, the stately English home he shared with Ono at the time. Bassist Klaus Voormann had known Lennon ever since the Beatles’ Hamburg days and played on most of Lennon’s solo recordings up to that point. Drummers Jim Keltner and Alan White had also worked with Lennon before. Keltner has been called “the leading session drummer in America.” White would subsequently join Yes. The third drummer on the album, Jim Gordon, was an L.A. session ace, also noted for his work with Leon Russell and Eric Clapton’s Derek and the Dominos. Another key contributor to Imagine was the legendary rock pianist Nicky Hopkins, revered for his playing with the Rolling Stones, the Who, the Kinks and many others. He had previously pounded electric piano keys on the Beatles’ “Revolution.”

New to working with Lennon was a phalanx of acoustic guitarists, recruited to anchor several of Imagine’s tracks. Among these were Wishbone Ash guitarist Ted Turner, who was brought into the project by another acoustic player on the sessions, Rod Lynton from the band Rupert’s People. Turner recalls being summoned to Lennon’s studio at around 11 p.m., just as a Wishbone Ash session was finishing up at the Beatles’ Apple recording facility. A limo was sent to collect him.

“I quickly jumped into a white Rolls Royce with Nicky Hopkins,” Turner recalls. “We got to chat and meet each other as we were being driven out to Tittenhurst, the white mansion. That’s really how it started for me.”

Even seasoned musical vet Jim Keltner felt overwhelmed by the scene at John and Yoko’s spacious Georgian mansion and its 20-odd acres of landscaped parkland. “Just driving down the driveway one foggy night,” Keltner recalled, “I remember thinking, ‘God, this really is a dream.’”

Lennon did a few initial sessions for the album at Abbey Road but quickly moved the project to his own studio, which was equipped with an eight-track tape machine and 16-channel board — state-of-the-art equipment at the time. He and Ono built Ascot Sound Studio into their home so they could enjoy complete creative freedom, away from the prying eyes of record company people and liberated from scheduling constraints at Abbey Road. The basic Imagine tracks were cut live-in-the-studio at Ascot and went down to tape fairly quickly. Lennon then decamped for the Record Plant in New York, where overdubs and mixing took place.

“I did 80 percent in the studio here [at Ascot],” Lennon later said. “It took seven days. Then I spent two days putting the violins on in New York.” In another account, however — for the pioneering underground rock mag Crawdaddy — Lennon wrote that the sessions took place over a total of nine days, six days at Ascot and three in New York. To the eternal frustration of rock historians, Lennon was notoriously slapdash about the finer details of his craft. The aforementioned Rod Lynton quickly discovered this when he entered the studio and spied Lennon’s legendary Epiphone Casino six-string electric hanging on the wall.

“John was a really great rhythm guitar player,” Lynton narrates, “but he wasn’t actually bothered about the state of his guitars — their condition. When I got in the studio it was just me, John and maybe a few technicians twiddling around. I said to John, ‘Do you mind if I have a look at some of the your guitars on the wall?’ he said, ‘Go ahead.’ I took down the [Epiphone] and the strings were crusty. At least they weren’t rusty, but definitely crusty. Later on, John took it off the wall and played it. He didn’t clean the strings or anything, and it sounded great. This was a guy who was brought up on guitar in the Fifties. ‘It’s a piece of wood with strings on it. You just play it, OK?’ I find that really kind of charming. He didn’t have guitar techs around or anything. He did it himself. George, on the other hand, was a perfectionist. He was far more on the ball in that way.”

Lennon and Harrison had both purchased Epiphone Casinos in 1966, partly to keep pace with Paul McCartney, who’d bought his own back in ’64. And in 1968, Lennon had his Casino’s original sunburst finished stripped down to bare wood, after the psychedelic folk-pop star Donovan told him it would improve the instrument’s sound. Lennon’s Casino is heard on many iconic Beatles tracks and became his go-to axe when he embarked on his solo career. Judging from photographic evidence, it seems to have been his chief, if not his sole, electric guitar for the Imagine sessions.

It is most likely the instrument heard in full cry on the first Imagine track that Lennon laid down, “It’s So Hard.” “I like singing blues rock, or whatever it is... I also like playing guitar,” Lennon wrote in his Crawdaddy piece. The 12-bar blues was one of his favorite songwriting idioms, a format he employed for “Yer Blues,” “Revolution,” “I Want You (She’s So Heavy)” and other Beatles classics. The raunchy, razor-blade burn of Lennon’s Chuck Berry-inspired soloing on “It’s So Hard” goes all the way back to something like “You Can’t Do That” from the Beatles’ earlier career, and probably originated in the murky depths of the Cavern Club. This is the sound that electrifies tracks like “Revolution” and Lennon’s 1969 solo single “Cold Turkey.” Lennon’s radically gutsy guitar work is one of the cornerstones on which the entire edifice of rock music rests.

“One of the greatest ever,” is how Jim Keltner rated Lennon as a rhythm player. “He had impeccable time. Most of the really great artists that I’ve worked with have been like that. And that’s where John’s confidence lay.”

Electric guitar was also Lennon’s instrument of choice for his notoriously nasty anti-Paul McCartney diatribe, “How Do You Sleep?” Lennon had taken offense at some lines from McCartney’s 1971 song “Too Many People.” He saw lyrics like, “Too many people going underground,” and “You took your lucky break and broke it in two” as digs aimed straight at him.

So he decided to retaliate. And in a pissing match, who’s gonna bet against John Lennon? The lyric for “How Do You Sleep?” is scathing. In three lethally crafted verses, Lennon dismisses the post-Beatles McCartney as an unimaginative “straight” who’d done nothing of note since the Beatles’ 1965 hit “Yesterday.” Ouch. But the coup de grace for Lennon was enlisting Harrison to join him on the track.

“There was no comment from George,” Ono recalled in ’98. “He was very careful. John was saying, ‘Ah, it’s a bit of a nasty one, isn’t it?’ Just kind of being very happy about it. George went along with it, but it wasn’t like ‘Yeah, let’s do it!’ It wasn’t like that.”

Harrison’s slinky, sinuous slide guitar solo and verse embellishments for the track perfectly echo the sardonic mood of Lennon’s lyric and vocal. Writing in Crawdaddy, Lennon rated it “George Harrison’s best guitar solo to date — as good as I’ve heard from anyone, anywhere.”

In an outtake included in the Ultimate Collection set — take two of the 11 that produced the master track — Harrison can be heard developing the solo, and also doubling the song’s chorus riff on slide. He and everyone else sound a bit lost. It was Ono who tightened up the chorus. In a famous scene from the Gimme Some Truth film, she and Lennon are seen discussing why the loose, reggae feel John had original envisioned for the chorus wasn’t working. “It’s too free,” she tells him. “It’s not funky.” Lennon’s not sure what she means at first, so she whispers to him that the musicians are “improvising too much.” Lennon barks out a command to the players — “OK, stop improvising. Keep it solid.” The result can be heard in the hard, riff-driven feel of the “how do you sleep” chorus on the master recording, with what seems an ironically “oriental” string overdub (pentatonic phrases in parallel fifths) wafting like some ill wind. It’s sort of like Ono adding an exclamation point to her husband’s caustic lyric.

Lennon co-produced the album with Ono and legendary record man Phil Spector, who was noted for his violent, confrontational and disruptive behavior in the studio. He’d shoot off guns in the control room and was known to have a problem with women, as witnessed by his conviction for the murder of Lana Clarkson.

“I’ve seen Phil crazy, but this wasn’t like that,” Klaus Voormann told me in 2010. “Not only on the Imagine LP, but on John’s first LP too [Plastic Ono Band], Phil Spector was fantastic. He was very subdued. He was cooperative. He never had a fight with Yoko or any disagreement. They got on really well with one another. He was funny. He was really listening and making a great sound.”

“Even with Phil there, John was running the show,” is how Keltner summed up the situation in 1998. “You can hear Phil’s production touches on the album, for sure, but John was very much in charge.”

The personal rage of “How Do You Sleep?” is well matched by the political fury of another classic Imagine track, “Gimme Some Truth.” The song reflects the angry mood among progressive-minded people during the Vietnam era and the years leading up to the Watergate scandal and resignation of U.S. President Richard Nixon. So it’s surprising that Lennon had started writing it amid the peaceful surroundings of the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi’s ashram in India, during the Beatles’ meditation retreat there in 1968.

He was obviously feeling less serene when he later finalized the lyrics. The song’s reference to “Tricky Dicky” — a derisive term often applied to Nixon at the time — would help trigger the president’s Stalinesque paranoia and make Lennon the target of an FBI investigation that would later threaten the artist’s ability to remain in his adoptive home of New York City.

The simple structure of “Gimme Some Truth” — A and B sections with no real chorus — suggests that Lennon couldn’t quite manage, or couldn’t be bothered, to refine his rage into a more fully realized composition. But it’s effective nonetheless. The insistent grind of Lennon’s chorused, arpeggiated rhythm guitar pattern drives the track forward as Lennon heaps invective on the hypocrisy, punditry and rhetoric of oppression that characterized the era.

Harrison contributes a wonderfully liquid electric slide guitar solo that’s rife with dramatic glissandos and passages of eloquent melodicism. He played the electric slide parts for the Imagine album on a Sonic Blue Fender Stratocaster, which was probably Lennon’s. Lennon and Harrison bought ’61 Sonic Blue Strats in 1965. But Harrison painted his own in psychedelic colors in 1967, rechristening it “Rocky.” If George did borrow John’s Strat, crusty strings apparently weren’t a problem. The single-coil sheen of Harrison’s tone on the track contrasts effectively with Lennon’s grungy arpeggios.

While electric slide had been mainly used for blues playing up through the late Sixties, Harrison took it to a boldly different direction. The legato lyricism of his approach reflects his studies in Indian music. While he rarely employs the intervals of Indian ragas in his slide work, his phrasing seems steeped in the protracted, languid lines heard in sitar melodies. His exacting note choice and skillful deployment of chromaticism and diminished scales further reflect the highly disciplined approach to improvisation in Indian classical music — with maybe just a hint of cheeky, British music hall panache enlivening the proceedings.

Always a stern self-critic, Harrison apparently didn’t think too much of his solo on “Gimme Some Truth.” “He’s not too proud of it,” Lennon wrote in Crawdaddy. “But I like it.”

Harrison switched to a Dobro for his slide work on the folksy, “Crippled Inside,” a diatribe against those who hide bigotry and other dark thoughts behind a veneer of respectability and conformity. “The middle eight melody is from some old traditional song I heard a few years ago,” Lennon noted in his Crawdaddy article, with characteristic nonchalance as to details. That song is, in fact, “Black Dog Blues,” a 1957 recording by the Stoneman Family that was revived as “Black Dog” by folk blues trio Koerner, Ray and Glover on their 1964 album, Lots More Blues, Rags and Hollers. This is most likely the version Lennon heard, as the disc enjoyed a kind of counter-culture cachet during this period. Neither song, of course, is to be confused with the Led Zeppelin song “Black Dog.” Black is the color and many is the number when it comes to canines in folk tradition. Borrowings from folk music are common in Lennon’s solo work. He pinched the melody for “Happy Xmas (War Is Over)” from a 19th-century English folk song titled “Stewball,” popularized in a 1963 recording by Peter, Paul and Mary.

“Crippled Inside” is one of several songs on Imagine where a pair of acoustic guitarists were employed to add weight to the track. In this case, Rod Lynton and Ted Turner joined Lennon in strumming on acoustics. Lynton recalls playing a Gibson J-45 on the track, with Turner on an acoustic 12-string that Lynton thinks might have been a Hagstrom. Both guitars came from Lennon’s own collection of instruments.

Lynton, who played on five of Imagine’s tracks, has fond memories of being coached by Lennon on guitar parts. “John would find a time when no one was around,” Lynton recalled. “He’d come up to me in the kitchen somewhere and say, ‘Come on, Rod. Let’s have a work-over on this song I want to do next.’ I’d ask him what he wanted me to play, but he said, ‘Do what you like. Do what feels right to you.’ On the one hand, it was incredible to be asked to play by someone of that caliber. But, by the same token, there was a lot of pressure in that.”

“John was very demanding of guitar players, especially,” Jim Keltner told me in 1998. “Being a guitar player, he would lean on them more. He would work with them a lot. With the rhythm sections, as long as it felt right to him, he didn’t mind.”

“He would never tell me what to play,” Klaus Voormann affirms. “I always played what I wanted and he would have accepted it.”

Voormann really shines on “Oh My Love,” one of the most poignant ballads on the Imagine album and, indeed, Lennon’s entire body of work. The track finds George Harrison playing clean, arpeggiated chording, and shadowing Voormann’s bass line at points, on a Gibson Les Paul that might be Harrison’s legendary “Lucy,” a ’57 goldtop painted over in red. (Photographic evidence is inconclusive.) With influences from Japanese koto melodies, the song is a meditation on the Zen-like sense of clarity that can accompany a really deep experience of love. It was based on a poem by Yoko Ono, making it one of the album’s truly collaborative Lennon/Ono songs.

The other one, of course, is “Imagine,” also constructed from one of Ono’s texts. While the track is, as noted at the outset, guitar-free, Lennon and Spector did toy with the idea of adding an acoustic guitar at one point. Rod Lynton recalls sitting in a molded plastic egg chair, equipped with stereo speakers, in one of Tittenhurst’s many rooms. He was smoking a joint when he received the summons to go into the studio and try putting an acoustic guitar part on “Imagine.” He took up his own guitar, a Yamaha 180 acoustic, and answered the call. Spector and Lennon were alone in the control room. Lynton tried three different approaches — straight strumming, arpeggiated chords and some counter-melodic lines. Each time, he stopped halfway through the take and drew his finger across his throat — the “cut” signal. “This isn’t working,” he told Lennon and Spector. The two men conferred briefly in the control room. Finally Lennon came on the talkback. “You’re right,” he told Lynton. “And that’s how I did myself out of playing on one of the greatest songs of all time,” the guitarist laughs.

But, in the end, everything turned out perfectly. As the outtakes and isolated tracks on the Ultimate Collection box set demonstrate, Imagine is much greater than the sum of its parts. Its enraged cries against injustice and impassioned pleas for peace ring just as plangently in our own time as they did in the early Seventies. The same goes for the record’s eloquence on the transformative powers of love. Some truths are eternal.

“I think my greatest pleasure is writing a song — words and lyrics — that will last longer than a couple of years,” Lennon said shortly after Imagine’s release. “Songs that anybody could sing. Songs that will outlive me, probably.”

In a career that spans five decades, Alan di Perna has written for pretty much every magazine in the world with the word “guitar” in its title, as well as other prestigious outlets such as Rolling Stone, Billboard, Creem, Player, Classic Rock, Musician, Future Music, Keyboard, grammy.com and reverb.com. He is author of Guitar Masters: Intimate Portraits, Green Day: The Ultimate Unauthorized History and co-author of Play It Loud: An Epic History of the Sound Style and Revolution of the Electric Guitar. The latter became the inspiration for the Metropolitan Museum of Art/Rock and Roll Hall of Fame exhibition “Play It Loud: Instruments of Rock and Roll.” As a professional guitarist/keyboardist/multi-instrumentalist, Alan has worked with recording artists Brianna Lea Pruett, Fawn Wood, Brenda McMorrow, Sat Kartar and Shox Lumania.