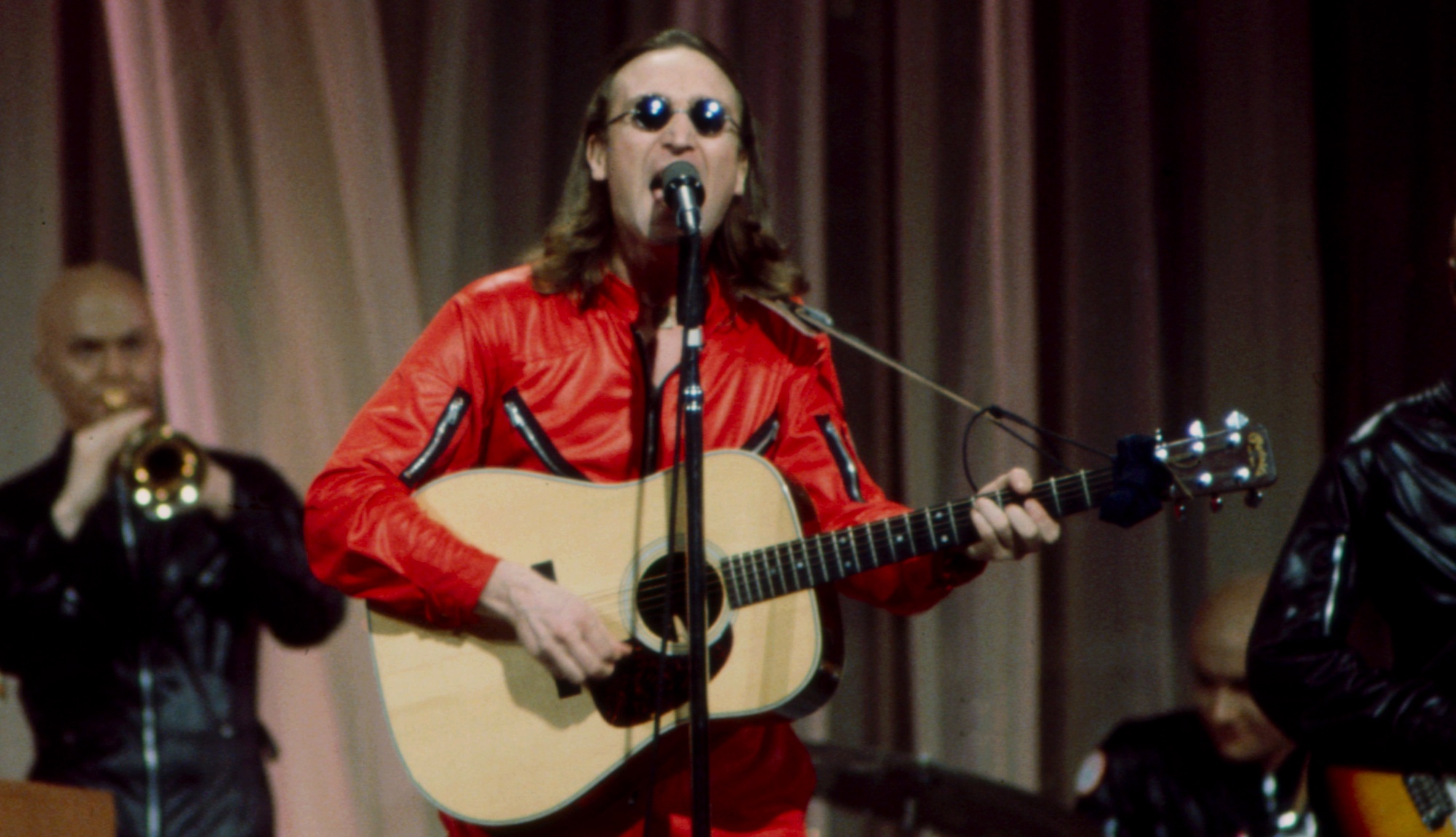

Venom Inc.'s Mantas Discusses 'Avé' and the Toxicity Surrounding the Venom Name

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

There’s a reason why guitarist Jeff “Mantas” Dunn and drummer Anthony “Abaddon” Bray—two-thirds of the members that created Venom’s classic lineup—can’t call themselves Venom anymore, while bassist and vocalist Conrad “Cronos” Lant continues to perform under the band’s original moniker.

And it’s not because the three musicians came to any sort of friendly, mutual arrangement regarding how to best share the legacy of the legendary British proto–black metal band.

“My mother had a serious stroke in 2005, which she later died from, and Cronos caught me at a really bad time,” explains Mantas from his new home in the outskirts of Portugal. “All I was thinking about was my mother. I didn’t give a shit about music or band names or anything. Cronos said he called to talk about the return of a product license and then he asked me if he could use the name Venom. I said, ‘Yeah, just go fuckin’ do it.’ I gave him verbal permission. I wish I hadn’t, but there you go.”

After he got the go-ahead from Mantas, Cronos quickly assembled a new Venom lineup that included his younger brother Antton on drums and recorded two predictable records—Metal Black (2006) and Hell (2008)—before Mantas returned to making music. The guitarist’s new band, M-Pire of Evil, featured his friend, bassist and vocalist Tony “Demolition Man” Dolan (Atomkraft) and, strangely enough, Antton, who played with the group for a couple years, then joined his brother in Venom.

While Cronos gave interviews to promote his first two post-2000 Venom albums, it was 2015’s From the Very Depths of Hell (named after the band’s old stage intro, “From the very depths of hell we bring you Venom!”) that really brought the beast out of the frontman.

“Suddenly, he tried to change the whole fucking history of the band, saying he formed it, and erasing the contributions of Abaddon and myself,” says Mantas in an even-keeled Newcastle accent that belies his onstage ferocity. “If you look at the history of the band, we started as a five-piece and Abaddon and I were the founding members. We wrote ‘Buried Alive’ before Cronos even joined the band. We brought Cronos in as a rhythm guitarist when one of the original guys left. My girlfriend at the time had a friend, and Cronos was her new boyfriend. So he came into the band and after a while, he moved to bass and then bass and vocals and we became a three-piece.”

Mantas and Abaddon now operate under the name Venom Inc., and they’re only allowed to do that because Abaddon invented and trademarked the Venom logo decades. ago. “It’s kind of annoying, but I really don’t care,” Mantas says. “People know who we are. They’re coming to our shows. And we’re making new music.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

The first Venom Inc. album, Avé, is a fine start. Realizing they’ll never be the most extreme or offensive players in the game, Mantas has opted for a NWOBHM and thrash-driven approach, with songs like the anthemic “Metal We Bleed” and the faster, more frenetic “The Evil Dead.” Both should sound good placed in a nest of viperous Venom classics.

Sure, the existence of two bands named Venom playing many of the same songs in concert is kinda confusing, but stability has never been a characteristic of Venom. From the moment they formed in 1979 in Newcastle Upon Tyne out of the ashes of three bands, Guillotine, Oberon and Dwarf Star, Venom has been a revolving door, especially for Mantas, who entered and exited three times before forming Venom, Inc.

The band’s powerhouse lineup—Cronos, Mantas and Abaddon—approached their blasphemous music with crosses blazing, crafting some of the most influential early Motörhead-inspired thrash and planting the fetid seeds of black metal with their blatantly Satanic lyrics. Back then, the members of Venom shared a common goal to be the loudest, most abrasive and evil band in metal without forsaking memorable verses and choruses.

“If you took Judas Priest, Motörhead and Kiss and put them all in a blender and let it all spill out, that would be Venom,” Mantas says. “But I’m old school. I love choruses, and I’ve always written with the audience in mind. I think, When can they join in when we play live?—and a good chorus is a great time for that.”

Hooky refrains notwithstanding, it took a certain level of perversity in the early Eighties to stand behind lyrics like ‘We drink the vomit of the priest, make love to the dying whore/We suck the blood of the beast and hold the key to death’s door” (“Possessed”). Unlike others that followed in their lyrical wake, including Morbid Angel and Mayhem, Venom’s songs were pure theater, with no affiliations to any religion, godly or demonic.

“Black Sabbath did the same kind of thing, but they didn’t push it far enough,” Mantas explains. “So we thought, Right, we’ll stuff it in your face and if you love it, great. If you run away screaming, even better. Fuck off. I mean, how much more blatant can you get than calling your first album Welcome to Hell and having a pentagram on the cover? There’s no hidden message there.”

Was there always friction between you and Cronos?

In the early days, I would say the closest relationship in the band was probably myself and Conrad, but we were all very volatile. It always seemed to be two against one—either myself and the drummer or it was myself and Conrad or it was Conrad and the drummer. We were never a band of brothers. But when we started out, we thought that we were going to be together forever. [laughs]

Venom seemingly came out of nowhere in 1981 with the single “In League with Satan”/“Live Like an Angel.”

Pretty much. Conrad was working at Neat Records. There was a thing in England at the time called the Youth Opportunity School, which was supposed to keep young people away from unemployment. So Conrad got an internship there. I used to hang out with him there and we repeatedly bugged the owner of Neat Records, David Wood, about recording a single. Finally, he gave in and we did “In League with Satan.” I reckon they put out 1,000 copies of those fuckin’ singles just to get us to shut the fuck up. It was like, “There it is. It’s gone out. It’s shit. No one’s gonna buy it. Now fuck off!” But of course, it blew up like crazy so then they let us go right back in and do Welcome to Hell.

Did Neat ever reject any of your musical or lyrical ideas?

I don’t believe Neat Records ever listened to a fucking record we put out and I don’t think they had a fucking clue what we were doing. They just knew that the shit we did was selling. So they said, ‘You wanna put that out? Okay. What is it? At War with Satan? Right, we’ll press that up.’ ”

Extreme music attracts strange individuals and some people didn’t realize you weren’t actually Satanists.

We got our share of letters written in blood; I don’t know if it was real blood. Once someone sent a box with a dog’s head in it. But we’ve never been targeted or felt threatened.

What kind of gear did you use in the band’s early days?

It was absolute crap. For Welcome to Hell, I went into the studio with a Flying V copy. I don’t even know who made it. I also had a Les Paul copy and a Strat copy. And I had a Marshall JCM800 and a cabinet I bought second hand by some company I never heard of. And I used a horrible big blue generic fuzz pedal for everything. The feedback was horrendous. It was total Spinal Tap. Everything went to 11.

Did you have better equipment when you recorded your second album, Black Metal?

I had an Ibanez Destroyer but all my other gear was the same.

Did you start by playing dive clubs and build your way up to festivals?

We totally avoided the club scene. One weekend we were rehearsing in a church hall in the West End of Newcastle in a rough area. The following weekend we were in a sports hall in Belgium playing for about 3,000 people. As the stagehands were setting up for our show, one of them walked by and he was singing [our song] “Sons of Satan.” And I looked and thought, How the fuck does he know that? The speed of our success was incredible. It was zero to hero. The first U.K. show we did was the Hammersmith Odeon in London.

You’re well known for your explosive stage shows. At your show at the Paramount Theater in Staten Island, New York, in 1983 you overdid it a bit with the pyro.

I recall that incident very well. We had two pyro guys. There were about eight boxes along the front of the stage and there were three cast iron pyro containers in each one. One guy poured the pyro powder in each one to the measured amount, and then just before the show, the second guy went, “Oh, fuck! No one filled the pyro pots!!” So he ran over and filled them up again and the resulting explosions were so colossal the impact completely wrecked Cronos’ bass stack. At the end of the show there was a hole in the stage and one of the pots was missing. It was found in the back wall of the balcony area. We were very lucky we didn’t kill somebody. But we wanted to be over the top. We didn’t want to be a safe band.

Did that dangerous lifestyle extend to your o_ stage activities? Was there excessive partying and adventures with groupies?

I would say for the other two, yes, but not for me. I’ve never been into the rock and roll parties. I’m this sort of quiet musician who just sits in the background. I mean, my drinking days actually finished before Venom. When I was in my early teens I woke up in my own vomit one day and thought, Ehh, time to stop this.

Why did you leave Venom after the 1985 album Possessed?

The personalities in the band had become incompatible and I wasn’t loving the music we were making. I’m not a fan of [the half concept album] At War with Satan, which was just a fucking nightmare. We wanted it to be complex, so we went back and forth into the studio and put parts down, refined parts, took parts out, joined parts together, overlapped parts. There was a lot of tape splicing because we didn’t have digital technology, and that took forever. And then for Possessed, I think we rehearsed the life out of it before we recorded it. When it comes to Venom, my favorite records are Welcome to Hell, Black Metal, Prime Evil and then Resurrection.

Were you and Cronos at each other’s throats before you quit?

We weren’t getting along. I actually stayed longer than I intended to. I can’t go into details, but the thing that made me leave was an incident in 1985 which I thought was… It happened at a festival, and there was another incident back at the hotel. They had nothing to do with music. They were just disgusting. And that was it. I walked away.

What possessed you to return to Venom in 1989 to record Prime Evil with Abaddon and Demolition Man? (Cronos left the band after 1987’s awkwardly polished Calm Before the Storm).

I didn’t want to, at first. I got the call about rejoining Venom and I literally said no and put the phone down. And then I was called again and again and again and I had a meeting with Abaddon and I still said no. And then they said, “Look, we’re going to get Tony Dolan in from Atomkraft.” Tony had been a friend of mine forever, and Tony said he would only come into Venom if I was gonna be there. So that’s how Prime Evil came around. Since we were already together and we were having a pretty good time, we did [1991’s] Temples of Ice, and [1992’s] The Waste Lands. We did a few good shows. But at the end it just wasn’t working so the band fell apart again [in 1993]. And then, obviously, the reunion with Cronos happened in ’95. We did a reunion concert with the original three members at the Wâldrock Festival in Holland and then the big concert was the Dynamo Festival in 1996.

Why did you play again with Cronos after what had happened?

The offers were good and the fans were screaming for it. And the reaction was amazing. It was like, “Venom are back, stronger than ever.” We were having a good time for a while, but it fell apart again. Old wounds started to open up and the old personalities started to come out again. We found it impossible to work together. We did Cast in Stone [in 1997] and then Abaddon and management wanted to fire Conrad. I didn’t want that because fans wanted to see all three of us. It was a mess. The record company finally stepped in and went, “Right, you have to fuckin’ get yourself to Germany now and do a fuckin’ album.” That’s when Abaddon left and Conrad’s brother came in and played drums on [2000’s] Resurrection. We only did a couple shows with that lineup; it quickly all went to hell. I found I really couldn’t work with Conrad anymore. And that was it. I made my final exit.

You and Tony Dolan formed M-pire of Evil in 2010 and recorded a pair of albums and an EP before you rejoined Abaddon in Venom Inc.

I never thought I’d work with Abaddon again. Me and Tony toured with M-pire all over the place. We played every toilet on the planet. Then, sometime last year, M-pire were invited to play the Keep It True Festival in Lauda-Königshofen, Germany. The guy who puts on the festival, Oliver Weinsheimer, asked Tony if we would do some Venom songs. He said, “Yeah,” and then Oliver went, “Well, what if Abaddon played with you?”

How did you react?

My immediate response was, “No, I’m not doing it.” And then we started talking about what Conrad was doing with Venom. I sent Abaddon a message and we both agreed to put a lid on all our differences and see how far we can take this thing. There were no rehearsals. We met in Germany, walked onstage together and played five songs. The place went absolutely crazy. We haven’t stopped touring since.

When did you decide to make another album together?

There was no intention to work together in the studio, not from my side, anyway. And then a few shows in I went, “I fancy writing some new riffs.” I’m constantly writing. I was throwing ideas down but I didn’t pass anything over to anybody. I was just recording these demos by myself. And then Jon Zazula [the former owner of Megaforce Records] said he wanted to manage us. He said, “Okay, one great record is going to change everything for you guys. I need some good songs.” So I got to work. I never envisaged that Nuclear Blast would step in, but Tony’s had a long association with Nuclear Blast Germany so before we knew it, we had a deal.

Did you enjoy writing Avé?

Not at all. It was extremely stressful. I locked myself in my studio and I just didn’t come out. My girlfriend was opening the door and throwing food in. We didn’t see each other for months. I wrote all the music, came up with a massive portion of the lyrics. Abaddon did the drums in Newcastle and sent me the files. I mixed, produced and mastered the album. The big surprise for everybody has been “Dein Fleish.” Apparently, that’s the song that sealed the deal with Nuclear Blast and the one they wanted to put out first. They said, “Whoa, that’s radically different.” I wouldn’t say it’s massively representative of the album as a whole, but nothing in Venom has ever come out the way I expect it to, so why should this be any different?

Jon is an author, journalist, and podcaster who recently wrote and hosted the first 12-episode season of the acclaimed Backstaged: The Devil in Metal, an exclusive from Diversion Podcasts/iHeart. He is also the primary author of the popular Louder Than Hell: The Definitive Oral History of Metal and the sole author of Raising Hell: Backstage Tales From the Lives of Metal Legends. In addition, he co-wrote I'm the Man: The Story of That Guy From Anthrax (with Scott Ian), Ministry: The Lost Gospels According to Al Jourgensen (with Al Jourgensen), and My Riot: Agnostic Front, Grit, Guts & Glory (with Roger Miret). Wiederhorn has worked on staff as an associate editor for Rolling Stone, Executive Editor of Guitar Magazine, and senior writer for MTV News. His work has also appeared in Spin, Entertainment Weekly, Yahoo.com, Revolver, Inked, Loudwire.com and other publications and websites.