Julian Lage Discusses His New Solo Guitar Album, 'World's Fair'

Julian Lage is much more than just a jazz musician.

While his musical foundation is rooted firmly in the world of bebop and swing, his playing encapsulates the full breadth of 20th-century American music.

The ghosts of Eddie Lang, Skip James, Doc Watson and Elizabeth Cotton haunt his vintage Martin 000-18, with which he creates a sound that is distinctly modern yet deeply indebted to the American folk music tradition.

Growing up in Northern California, Lage was something of a guitar prodigy. Practically before he could read, he was sitting in on jam sessions with David Grisman and Bela Fleck; and by his early teens, he was touring with legendary jazz vibraphonist Gary Burton.

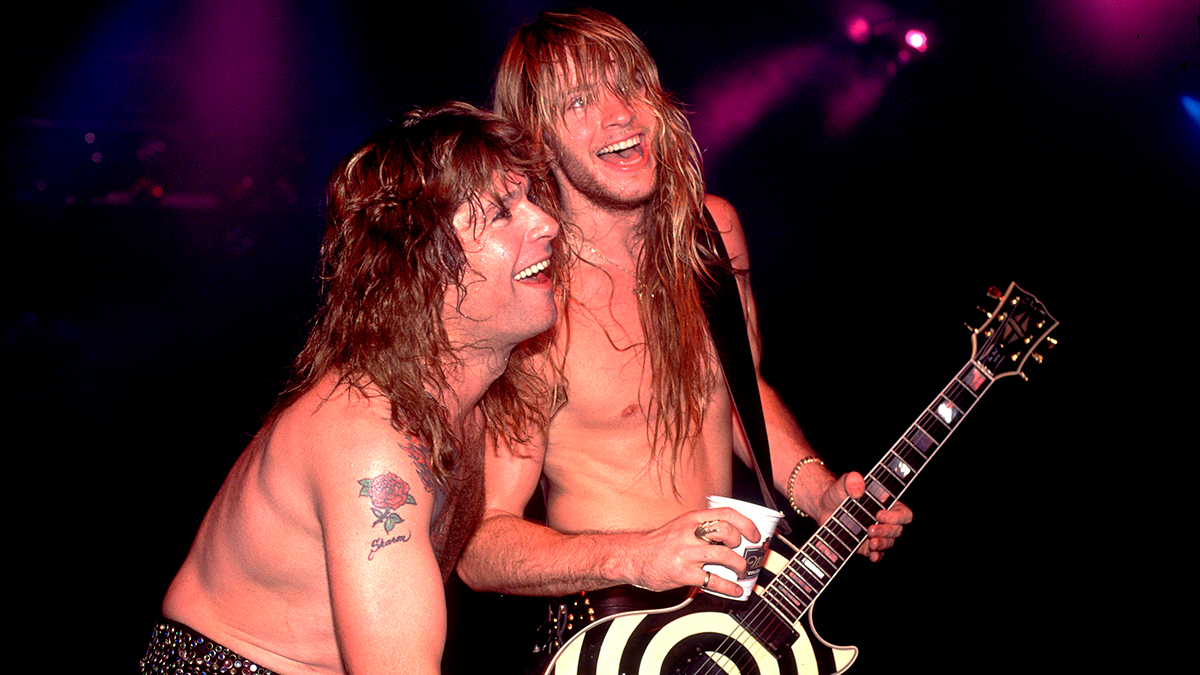

In addition to leading his own ensembles, Lage has since performed with too many stellar musicians to recount. Whether playing fiddle tunes with Punch Brother’s guitarist Chris Eldridge or free jazz explorations with experimental guitar wizard Nels Cline, his stunning virtuosity and melodic intrepidness are always on display.

Lage’s upcoming release, World’s Fair, is a solo guitar project he says was inspired by classical master Andres Segovia. Though he’s quick to describe himself as a jazz guitarist first and foremost, World’s Fair showcases a more orchestral approach to the instrument. For Lage, the guitar is its own tiny orchestra, and in his hands the musical possibilities seem endless.

While driving north to a gig in Portland, Oregon, with Cline, Julian spoke with me about his approach to improvisation, playing with dynamics and performing solo on his upcoming album.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

GUITAR WORLD: You have such a strong melodic sense to your playing. Even when you’re playing these fast, complicated lines, they always sound very musical. As a guitarist, it’s so easy to get stuck in certain patterns and shapes while playing a solo, but you seem to embrace what’s cool about the linear nature of the guitar while always retaining a high level of musicality. How do you keep this balance while improvising?

Well, thank you, first of all. I think it’s a fascination I have with the guitar as a mechanism. I love the design, the open strings, the way it’s tuned—it can be challenging, and you’re totally right, there are traps you can fall into; but it’s also one of the most lyrical instruments in the sense that you can play really simple things and they will sound kind of righteous.

Even just playing a C major triad can be so satisfying! I would say as a directive, what I envision starts with the guitar’s design. I don’t really have to avoid certain things; I just end up doing what sounds obvious to me. A big part of what gives my playing a sense of melody is that it has an intervallic architecture. I think in terms of ratios, where I will play a bunch of notes really close together chromatically and then notes that are wide apart. I’m almost playing with—not deception or illusion—but implying this breathing organism that is at times really tight and at others really open. This intervallic approach is how you get a different sense of orchestration that wouldn’t typically be applied to the guitar.

I love the way you utilize dynamics. It creates such an expressive style that is so unique to you. How conscious are you of playing with a sense of dynamics?

I think it’s as simple as that I’m a sucker for as wide a dynamic range as you can have on the guitar. I love Django Reinhardt, for example, who is the most unbelievably dynamic, fluid and dramatic player. I’m drawn to players that have a sense of drama, ones that know how to drip you and make you feel like the end of their solo coincides with the end of the world! I think you’re either drawn to that style or you have other ways of achieving drama.

I’ve always been fascinated with what the opposite of that style of playing would be, because if I know what the opposite is, I can work in the other direction. So the opposite of dramatic playing might be very monotone and lack variation within the intervallic structure. Instead, I might purposely play with dips in volume and incorporate a balance of staccato and legato lines. It’s conscious in the sense that I’m making an effort to do it, but I always feel like I could do more. I think, “Man I could have made it sound so much more like a voice if I didn’t play those five notes at the same volume.” It’s always a work in progress.

The compositions on this album incorporate a wide range of genres of essentially American music. There’s jazz, folk, bluegrass, it reminds me a lot of what David Grisman did back in the Seventies. How did you go about cultivating this style?

Grisman is totally one of my life heroes, so is Bela Fleck—these are guys I was around a lot as a young person.

People always say, “You know Grisman invented Dawg Music,” but if you listen, it was really just music. He took his favorite aspects of everything. I think rock bands do this all the time and so do pop artists to a large degree, but maybe in jazz it’s still kind of novel. People say, “Wow, you would take that and put it with that!” I still consider what I do jazz, but I totally agree with you that what I’m doing is distinctly American in a way. There are certain aesthetics on this record that you’re more likely to find in contemporary acoustic chamber music, American classical music and old-time fiddle music.

The same is true with the rhythmic propulsion on the record. I purposely stayed away from playing anything with a swing feel, because I didn’t think solo guitar was the format for me to play swing. Instead, I incorporated things like Travis-picking styles and doo-wop styles. That feel is also a big part of what gives the music a location. So it wasn’t a conscious thing, but I was around people who did that very naturally and maybe I took it for granted.

Speaking of swing feel, I’d imagine a lot of people would except this album to be more of a Joe Pass solo guitar thing, but it’s really not. You’ve said Segovia was a big influence for this album. Can you speak to that?

Yeah, good point. Segovia is my hero. He and Julian Bream are just the greatest. It’s funny; when I was younger, I thought I wasn’t smart enough to like him. I thought his playing was the ultimate in virtuosity. But then when I started listening to him, as I got older, I thought, “This is music I could just put on in my house and listen to all day.” There was no elitism; it was just such rich music. There was also a legitimacy that Segovia brought to the guitar as a concert instrument. He made it so it was no longer this weakling trying to fit in with an orchestra, but also not this bombastic thing.

What he did was on par with someone sitting down at a Steinway piano. So that was the inspiration: I wanted to make a record that I would want to listen to in the background. I also wanted to keep it consistent with having three to four minute songs I could play for anybody and not have to say, “Oh, I wish you could hear this with a bass player.”

Segovia’s probably the all-time greatest example of that. I don’t pretend to think I’m on his level, and I’m also coming at it from a very different angle, but I do think it’s worth striving for. As for the Joe Pass and Martin Taylor School of solo guitar, those guys are insane! They’re so good. I also have enough respect for them to realize I don’t do what they do; and that since it already exists at such a high level, I should do something different.

You mentioned to me earlier you’re currently driving to a gig with Nels. You’ve played in a number of intriguing duos already in your career. How would you compare solo playing to playing in a duo?

Playing in a duo is kind of the dream for me. Playing with Nels is the ultimate. Pretty much every duo I’ve been a part of is because I like the person and they happen to play music and then we happen to play together. It hasn’t been deliberate like, “The sound of two guitars is what I’m looking for.” Instead it’s just been because I love Nels or whomever else I’m playing with. We just both happen to play guitar. Solo playing is about learning how to be stronger in different ways.

A lot of my musical life has been about responding and interacting, and with solo guitar I still have to do that but with myself. I have to be very resourceful when it’s just me and enjoy even the little stuff that I play. It can’t all be explosive, fast stuff; I need more mundane, beautiful things. It’s sort of a lesson in self-compassion, because if you start to hate what you’re playing it can be a very long night. And then when I come back to a duo, it’s like I’ve come back to a big band. I feel like the sound just quintupled! That all makes it pretty fun, they go well together.

For more about Lage, visit julianlage.com.

Ethan Varian is a freelance writer and guitarist based in San Francisco. He has performed with a number of rock, blues, jazz and bluegrass groups in the Bay Area and in Colorado. Follow him on Twitter.