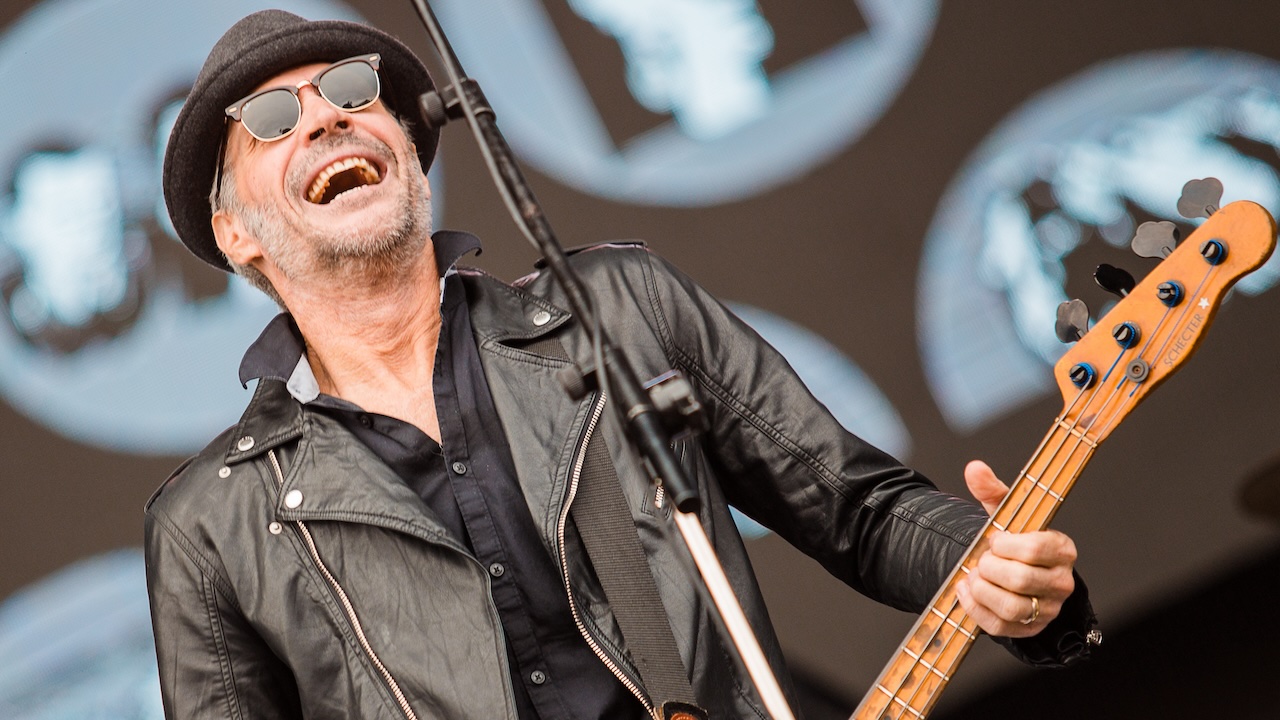

“When I was a kid, I thought bass playing was about throwing up and cutting yourself – I blame Gene Simmons and Sid Vicious”: Bad Religion’s Jay Bentley on his bass-playing influences and the “best-sounding P-Bass he’s ever heard”

Vomit and blood may be punk rock, but it’s not what you might expect from longtime Bad Religion bassist Jay Bentley

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

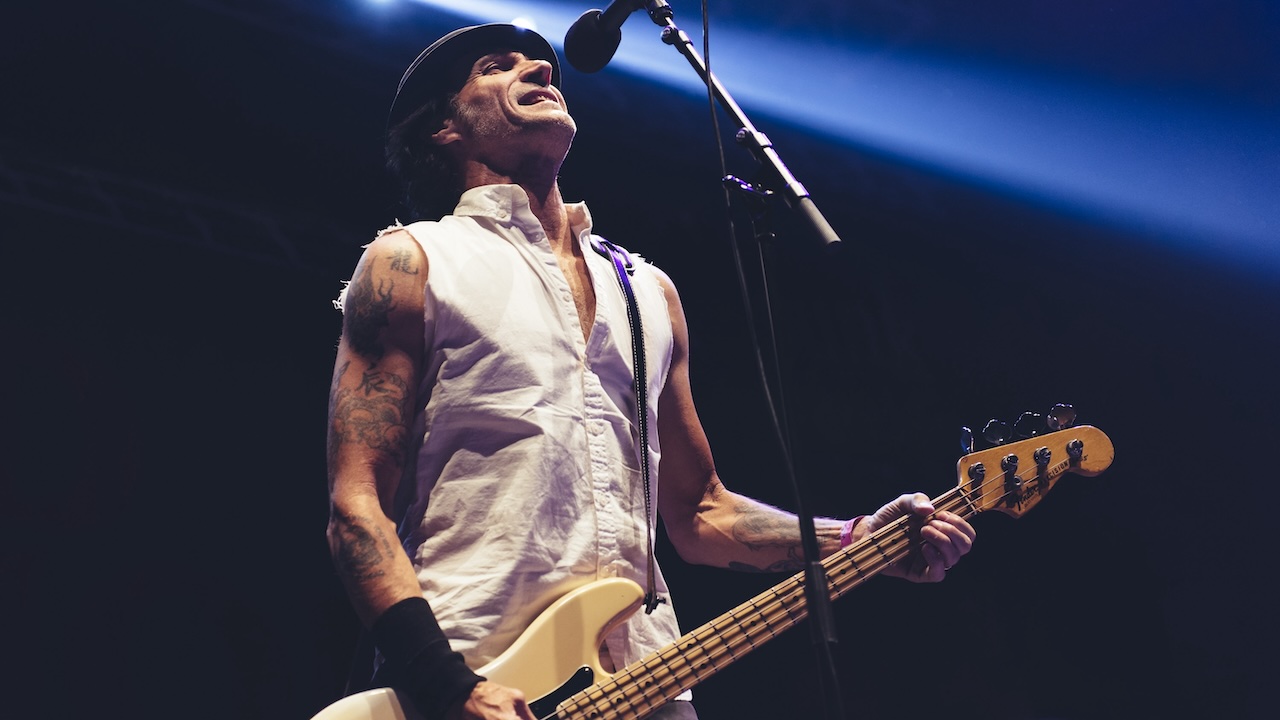

“I used to think bass playing was about throwing up and cutting yourself with razor blades,” Jay Bentley told Bass Player back in 2004. Vomit and blood may be punk-rock, but it's not what you'd expect from the longtime bassist of Bad Religion, one of the genre's most celebrated and serious bands.

“When I was a kid, I thought bass players were the devil; they spit blood and breathe fire. I blame Gene Simmons and Sid Vicious! I thought, damn, playing bass guitar is one hard job! Thank god for the Clash – Paul Simonon was cool, without the razor blades.”

Like Bentley, Bad Religion evolved from early- 80s hardcore punk innovators into a mature, politically charged group of notable musical sophistication. Most of the band’s righteously vicious songs still charge along at blistering tempos, but Bentley sees his role as having evolved away from a drum-locked low-end gallop into a counter-melodic voice that complements the guitars and vocals.

Bad Religion has also gracefully weathered shifting lineups, the surreal ride of a major-label hit album (1994's Stranger Than Fiction), and a subsequent conservative shift in public taste.

The following interview from the Bass Player archives took place in July 2004.

Describe your role in Bad Religion.

“I want to figure out how I can complement the song without stepping on anybody's toes. I'm most concerned with Greg Graffin’s harmonies and vocal patterns. He's quick with words, so if I start getting complicated, they get slurred-and suddenly you're not getting the meaning of the song.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

How did you develop the melodic lines on The Empire Strikes First?

“In the studio I just wanted to get a good basic track down first, so everybody could layer on top of it. Then, once the vocals were done, I'd come in later and redo everything. That gave me a chance to take the finished guitar parts into account, since many songs weren't complete when we were tracking.”

On Overture, there's a super-deep bass part that sounds like a synth.

“That was actually stuff that Brett Guerewitz and his cohort Atticus Ross, from Trent Reznor's band, came up with. It came from this goofy thing we started playing in rehearsal, which evolved into a cool and ominous intro. The band laid down a basic track and gave it to Atticus to program. We got it back, and it was way different from what we played. Then I had to figure out how to do it live!”

How do you cope with touring?

“It's all about finding something to do with the 12 hours a day you spend waiting to play. I've been to every museum, library, art gallery, park, and national monument there is! Also, if it's an outdoor tour, keep your stuff clean! The amount of damage that dirt will do to your gear is crazy.”

Who are your bass playing influences?

“Paul Simonon was the first guy I really embraced as a bass player. After emerging from my Kiss phase, I got into bands like the Jam, Devo, and the Clash.”

On Atheist Peace are you using an envelope filter during the outro section?

“I wouldn't know! That was more post-production stuff. Digital editing has changed everything. It's 10 times what the Beatles ever had! We were just flying through parts and putting raw material down on tape. Then everybody but the producers pretty much left. It was like, ‘Good luck – see you later.’”

What gear did you use in the studio?

“I used the same '78 Fender Precision Bass that I've used since 1988 for every record we've made. I don't know why this bass sounds so different from every other, but I've played it for producers and they say it's the best sounding P-Bass they've ever heard. Now I lock it in a case and only bring it out to do records!

“I used an Ampeg SVT, an old Orange guitar head, and I blend the amp sound with a direct signal. When you combine a bass amp with a guitar amp, it gets a piano-like quality that improves clarity. Since Bad Religion has these crazy distorted guitars, clarity is crucial. I mean, sometimes you can't tell what chord somebody is playing; that's how thick the distortion is.”

How about live?

“I just use an SVT and play exclusively with a pick and an old Schecter Tele-style bass. You'll see me play with my fingers only if I drop the pick. I never liked playing fingerstyle with Bad Religion. Attack is the most important thing: When you're ham-fisting it, going a hundred miles per hour, pick is the way to go.”

How has being in Bad Religion for so long affected your playing?

“I know what's best for Bad Religion. I always feel uncomfortable in other situations. The biggest change in my talent level is that I used to hear what I wanted to play, but I couldn't do it. Now, I hear it in my head and I just automatically play it.”

What advice do you have for a young punk-rock bass player?

“Learn everything and then forget it all. That way you've got this wealth of knowledge inside you, but you're not tied down by rules of what you're supposed to do. Knowing what you can do physically is much more intriguing than some rule that says, ‘No, you're not supposed to play that there.’ Leave the professional side to the other people. You're just a bass player!”