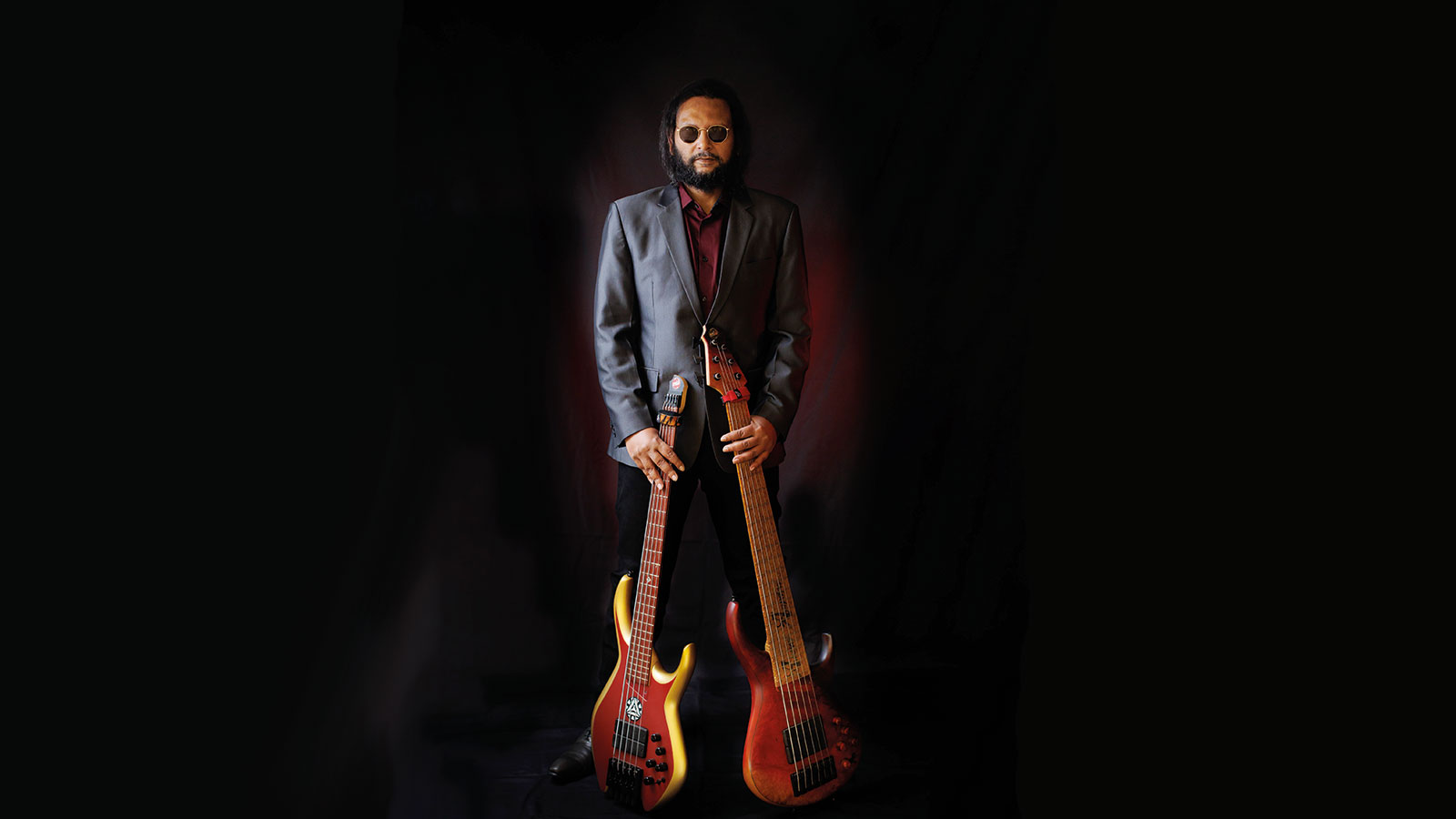

Bassbaba Sumon on overcoming relentless setbacks, studying Stu Hamm and bringing Bengali scales to rock bass

The Bangladeshi bass icon has survived multiple bouts of cancer, a near-fatal road accident and a stroke, but is still performing at the top of his domestic music industry

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Saidus Salehin Khaled, known as Bassbaba (‘Bass Father’) Sumon or just as BB, is a bassist, singer, songwriter, solo artist, and bandleader from Dhaka, Bangladesh.

Known for his membership of the bands Feelings and Aurthohin, as well as many collaborations and solo releases, BB is renowned in his home country but less known in the West, where Bangladeshi rock music is seldom heard.

A bass player since the age of 13, when he was inspired to pick up the instrument by Steve Harris of Iron Maiden, BB began writing and recording in his mid-teens and was a solo and session performer by the age of 17.

His first solo album was released when he was 20, and by the 2000s he was a member of the arena-rock band Aurthohin, which he continues to lead today. He was the first ever domestically-based Bangladeshi musician to receive a gear endorsement, in his case by MTD, and he’s also on the roster at Boss, Roland, Temple Audio Design, Gruv Gear, Gallien-Krueger, Bartolini, and La Bella.

However, in the last decade BB’s career has been seriously obstructed by a relentless sequence of health issues, which he discusses with us below. He’s come through them all, as creative a bassist and performer as ever: There’s a lesson there for all of us.

If you’re comfortable with it, BB, please talk to us about the health problems you’ve had.

“Sure. I was diagnosed with cancer back in 2012. First I had two tumors in my spine, but that cancer was at a very early stage, so after the surgery I got better. Eighteen months later, I was diagnosed with stomach cancer, and this was really serious because it was at stage three and almost stage four. The doctors had to remove 85 percent of my stomach.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“After that, I had a brain tumor and they had to remove that, and after that, I got skin cancer: I had several tumors on my skin, so they had to remove those. Believe it or not, after that the stomach cancer came back, and they had to remove my whole stomach – so I’ve been fighting cancer for a long time. Now I have no cancer issues.”

What happened then?

“I got into a car accident, and my spine was totally fucked up – sorry for my language. The doctors put 14 screws in my spine, but those surgeries, which took place in Thailand and in Singapore, weren’t successful.

“The first doctor put six screws in, then the second doctor put in another four screws, and then another two screws and so on: I was in very bad shape. But then I went to Germany, which is really good for this kind of surgery, and when the doctors over there saw my spine, they removed all the screws and put six more screws in again.”

How did that affect you?

“I could walk, and I could stand for a short time, but I couldn’t sit, so I couldn’t play bass for long. I couldn’t record. I couldn’t do anything, so I was totally in bed for three and a half years. I couldn’t play a bass while I was lying down, so I was totally off the grid for those years. I’m the singer, the songwriter and the composer of my band Aurthohin – which means ‘meaningless’ in Bengali – so we totally stopped our activities.

We did a comeback gig in a stadium with 30,000 people there, and all of them were singing our songs. We thought that people forgot us, but they didn’t

“For four years, we were nowhere. I was taking painkillers, and I got hooked on them. Because I was always in bed, lying down, I had a stroke. My left hand, my left leg and my left side were paralyzed for four to five months, so I had to do a lot of physiotherapy.”

How badly was your bass-playing affected by your stroke?

“I needed very serious rehabilitation to come back from that. I’m still practicing every day. Right now I’m at 80 percent of my ability, I think, because two of my fingers are still a little stiff. But eventually I’ll get there. I know that, because a long time ago my jaw got dislocated in the middle of a concert while I was singing. In the middle of a song, I couldn’t move my jaw, and I had to stop the concert and go to the hospital.

“In Bangladesh, the medical system is not that advanced, so the next day I went to Singapore, where they told me that my jaw ligament was not torn, but it had stretched, like elastic does. The doctor gave me a brace to wear on my mouth. He told me ‘For the rest of your life, you have to put this on, and you cannot sing’.

“I told him, ‘You’ll see – I will sing someday’. And you know what, it took me 18 months to do it. I went back to the stage, and I was wearing that brace. Then I recorded an album wearing that thing. After three years, I threw it away. The doctor told me, ‘I don’t know how you did it. I’ve checked everything, and you’re okay’. So I have this confidence that whatever comes my way, I will overcome it.”

We did a comeback gig in a stadium with five more bands. There was something like 30,000 people there, and all of them were singing our songs

When did you become fully healthy again?

“Not for a long time. After the stroke I had a second brain tumor, but fortunately it was benign, and they removed it. The last thing was that I had a broken bone in my spine, which was in a very sensitive place. The doctors told me that they were not taking the risk of doing surgery, so they did some kind of electronic vibration therapy that moved the bone away from my spinal cord.

“Finally, I started my music career again. We did a comeback gig in a stadium with five more bands. There was something like 30,000 people there, and all of them were singing our songs – we didn’t even have to sing. It was an amazing experience. We thought that people forgot us, but they didn’t.”

What does that much suffering do to a person?

“A doctor once told me that I might only have eight to 14 months left to live, when I had stage three cancer, and I was very scared. For two weeks, I never told anyone, even my family members, that I had cancer. I isolated myself, because I didn’t know what to do, but one of my friends came to see me.

“She lived in the States, and she also had cancer: She has passed away since then. She told me, ‘Live your life. Even if you only have eight months to 14 months, just live your life’. That changed me, and I made a bucket list. One of the items on that list was a road trip in the United States. I went to the States and I drove 10,000 miles.”

How has your mental health been affected by your physical issues?

“I never actually got depressed. I was sad, and sometimes I was frustrated, but I didn’t get depressed. I thought ‘Right now I’m going through a very bad phase, but that means that the good times are coming – I just have to be patient’. That’s exactly what’s happening. My agent is receiving at least 10 to 15 calls a day for our gigs.”

Bass guitar was regarded as a backup instrument in my country. People recognized the drummer, people recognized the guitarist or the vocalist – but they never gave any recognition to the bass players

Has all this made you stronger?

“Absolutely. One thing I know is that I’m not scared of cancer any more. Trust me, I’m not bragging, I’m not telling a lie. I’m not scared of cancer any more. So many times, the cancer has come, and the cancer has gone away. Nowadays I counsel people who have cancer. I try to help them, because I know that 50 per cent of recovery is in the mind.”

Define your music for us.

“Well, I grew up listening to Iron Maiden, Black Sabbath, and Deep Purple, but I’m also a very big fan of George Michael and Yanni and Abba, so when I write songs, all of those influences are fused in my music. I have more than 200 songs published in Bangladesh, from easy listening and soft pop to thrash metal and metalcore – from old-school heavy metal to Killswitch Engage to Iron Maiden to something like John Denver. You’ll find everything there.”

What was the role of bass in Bangladeshi music when you started playing?

“Back then, bass guitar was regarded as a backup instrument in my country. People recognized the drummer, people recognized the guitarist or the vocalist or the keyboard player – but they never gave any recognition to the bass players back then.

“The keyboard and the vocals were the main things in music at the time. If someone played bass, their friends would be like, ‘What are you playing? We don’t understand these sounds’.

Whenever we used to do western music, most of the people used to say ‘What kind of music are you doing here? Why are you screaming like that?’

“If I recorded something, and showed it to my friends, they would be asking me, ‘What instrument did you play?’ because I couldn’t make them hear the sound of the bass. They couldn’t recognize the sound, because Western rock and jazz were never popular in our country.

“Whenever we used to do western music, most of the people used to say ‘What kind of music are you doing here? Why are you screaming like that? Why is there so much guitar and drums?’ It’s very different now.”

How did you become a bass player?

“I watched Iron Maiden’s Live After Death VHS in 1987, when I was 13 or 14. That changed everything. When I saw Steve Harris playing the bass, I was blown away, and I instantly made a decision that I was going to play bass guitar.

“I removed two of the strings from my acoustic guitar because I couldn’t afford to buy a bass, and there was no such thing as an acoustic bass guitar in our country. I had a cassette of that Live After Death album, but it accidentally recorded at double speed, so that was how I learned to play bass. That gave me fast fingers.”

What was your first bass?

“At first I had no bass guitar, only that old acoustic guitar, so I used to borrow bass guitars from my friends. One of my friends loaned me a bass guitar – a very bad, Indian-made bass with no name – so I used to play that.

“When I was 17 years old I joined a band as a bass player: a very big, mainstream band in our country called Feelings. They are the most famous band in Bangladesh. Their singer James is by far the most famous rock icon of Bangladesh, ever. He’s the guy.

“I was with the band from 1990 to ’93. When I joined that band, I didn’t tell them that I didn’t have a bass. I used to borrow basses from my friends and bring a different one to every rehearsal. Finally the vocalist asked me ‘What is your bass?’ and I told him that actually I didn’t have one, so the band bought me a Yamaha BB. That was in 1991, four years after I started playing bass.”

You’re the first Bangladeshi musician to have a foreign endorsement deal, correct?

“After that Yamaha bass, I bought a Warwick, and I loved it. I was playing that for a long time. Then I went to a guitar store in Singapore and I found a Tobias bass and I loved that too. I bought the four-string version, then the five-string version. I researched them on the internet and saw that the Tobias brand was no longer on the market, but that Michael Tobias, the luthier, had opened his new company, MTD.

When I first heard Stu Hamm, he blew me away. I was like, ‘What the hell am I listening to?’

“I contacted Beaver Felton at Bass Central in Florida and said, ‘I’m from Bangladesh and I want a custom MTD. I know that you sell the most MTDs in the United States’. Beaver contacted Mike, and then Mike and I talked by email and he made me a five-string bass, which I bought through Bass Central.

“Mike knew what kind of sound I wanted, and I really loved it. I still play that bass most of the time. Later I visited Mike’s shop, and we became really close, like family. He told me, ‘If you want, I can put your name on my website as an official artist’ and I was like, ‘Oh my God, this thing has never happened in Bangladesh, ever’. It was an honor. Mike is a really, really good friend of mine. He has supported me all the way.”

You use a lot of advanced techniques in your playing. Did you take lessons?

“In Bangladesh, there was no way to take lessons from anyone, but one thing helped me a lot. When I first heard Stu Hamm, he blew me away. I was like, ‘What the hell am I listening to?’ My parents were visiting London at the time, and I asked them to buy me Stu’s VHS tape Slap, Pop And Tap For The Bass. I learned all the slap techniques from that tape. Stu and I have also become friends.

“A few years later, I learned about Victor Wooten’s playing and I went to his 23-day workshop. Before I went there, I studied his video, Super Bass Solo Technique. So my influences are Steve Harris, Stu Hamm, and Victor Wooten.”

How does the music of your own country influence your bass playing?

“I write Bengali music, so my note choices are different to those of Western bassists. I learned techniques from the Western players that I mentioned, but the scales that I use are from Bangladeshi music.

“For example, the harmonic minor falls in with Bangladeshi scales, but if we change the mode then it will become a little bit like Indian classical music. You can hear this when you listen to John McLaughlin or Shakti. What we do is something in between Western music and Indian classical music, I guess.”

Thank you, BB. There’s a lot for us to learn in what you’ve said...

“It’s been a pleasure, because music is what I believe in. I don’t do music because it’s my hobby. I don’t do music because it’s my profession. I do it because it’s my passion. The way I see it is that I’m living a bonus life. I don’t get sad – I believe that happiness is a choice, and I choose to be happy.”

- Soul Food Part I is out now.

Joel McIver was the Editor of Bass Player magazine from 2018 to 2022, having spent six years before that editing Bass Guitar magazine. A journalist with 25 years' experience in the music field, he's also the author of 35 books, a couple of bestsellers among them. He regularly appears on podcasts, radio and TV.