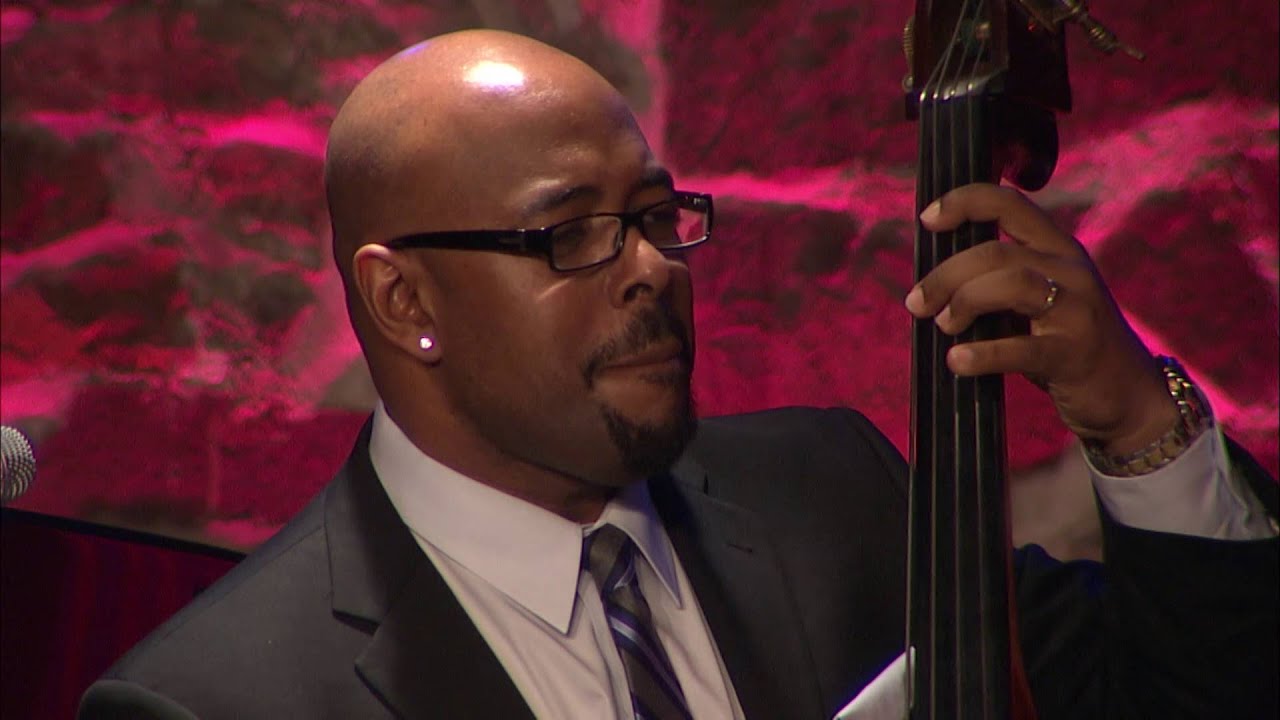

Christian McBride: “I was doing things on the double bass that I wasn’t supposed to. It helps to be a rebel sometimes“

The jazz and session maestro looks back at his career in bass

The great Christian McBride is equally at home with a stand-up bass – playing jazz with legends like Chick Corea, Diana Krall and McCoy Tyner – and the electric instrument, in connection with soul titans James Brown and Aretha Franklin as well as rock stars such as Paul McCartney and Sting.

A prolific solo artist, he has a sizeable discography of his own behind him as well as countless sessions; his latest album, The Movement Revisited: A Musical Portrait Of Four Icons, is out now.

Christian, does your double bass playing inform your electric technique?

“Actually it’s the other way around, because I started on the bass guitar. When I moved to the double bass, I just carried on doing a lot of the things I had been doing on the electric, not knowing that I was not supposed to be doing those things at all!

“I think it helps to be a rebel sometimes. Naivety can work for you sometimes – because if you don’t know the rules, you don’t know you’re breaking them, which for musicians, is often a useful thing to happen.“

Given that your father Lee Smith was also a double bass player, why didn’t you start with that instrument yourself?

“Simply because there wasn’t one available to me. When I joined my middle school in Philadelphia, which was a really good school, I was enrolled in the orchestra, and of course I had to play an orchestral instrument.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“Double bass was not my first choice – I actually chose the trombone – but I was really bad at it, so the brass instruments teacher recommended that I switch to double bass as he knew I already played electric bass.“

I joined the senior school jazz band when I was 12, and I played electric bass and double bass. That was when I really started to have some fun!

Was there a transition period while you got to grips with the differences between the two instruments?

“There wasn’t, and again, it was another instance of naivety being a positive influence on me as a musician. I looked upon the double bass as a bigger, heavier, stand-up version of the electric, and that’s how I approached my playing when I was learning.

“While I was in the school orchestra, I was playing to a chart, because there is no room for improvisation in an orchestral setting. My bass teacher recommended that I join the senior school jazz band.

“I was actually a year too young to join, but she said they would probably make an exception for me, as she thought I was musically proficient enough to fit in. I joined that band when I was 12, and I played electric bass and double bass. That was when I really started to have some fun!“

Do you prefer one instrument over the other?

“I’m not at all sure that there are differences you can measure as good or bad. I’ve certainly never thought about the two instruments in that way, and I’ve never compared them as being better or worse from each other. I think of the double bass as Mother Earth, and the electric bass as The Restless Child.

“The double bass has the fuller sound, but not as much volume; the electric bass has the edge in the volume, but it doesn’t have that full sound. I think at the end of the day, the music you’re playing is always going to dictate which of the two is the suitable choice.“

Playing bass guitar is not about you, it’s about your role in the band, and if you remember that, you’ll get work and be a player people want to have around

What do you think makes a successful bass player?

“Well, I think that a lot of bass players are impressed by players who can play fast, because they think that’s what good bass playing is about. The truth is, the bass players who are getting a lot of work, who are doing a lot of sessions, or working a lot with different live bands, understand what the role of the bass guitar player is—and that role is to accompany.

“You’re there as a support to the other instruments in the band you’re playing with, and if that’s what you’re doing, then playing fast really shouldn’t be crossing your radar. The exception to that rule is, if you’re hearing music that gives you ideas about playing faster to act as that support, then that’s okay – but that’s not the same as playing fast simply because you want to, or because you can.

“That is not fulfilling your role properly as a bass player. You are a traffic cop, or a navigator; you’re there to underpin things, and to make people dance. Playing bass guitar is not about you, it’s about your role in the band, and if you remember that, you’ll get work and be a player people want to have around. When people don’t notice you, that means you’re doing your job right.“

What was your first electric bass?

“It was a model called a Kingston, and it came from a pawn shop in west Philadelphia. It had a short-scale neck. I had never seen another Kingston bass before the one I got, and I’ve never seen one since.

“I played that bass from when I was nine to when I was 13, and I had the same experience that a lot of musicians starting out have – you get your first bass and it’s actually not a good instrument on a lot of levels, but you don’t know any better, so for you, that is how bass guitars feel, and how they play.

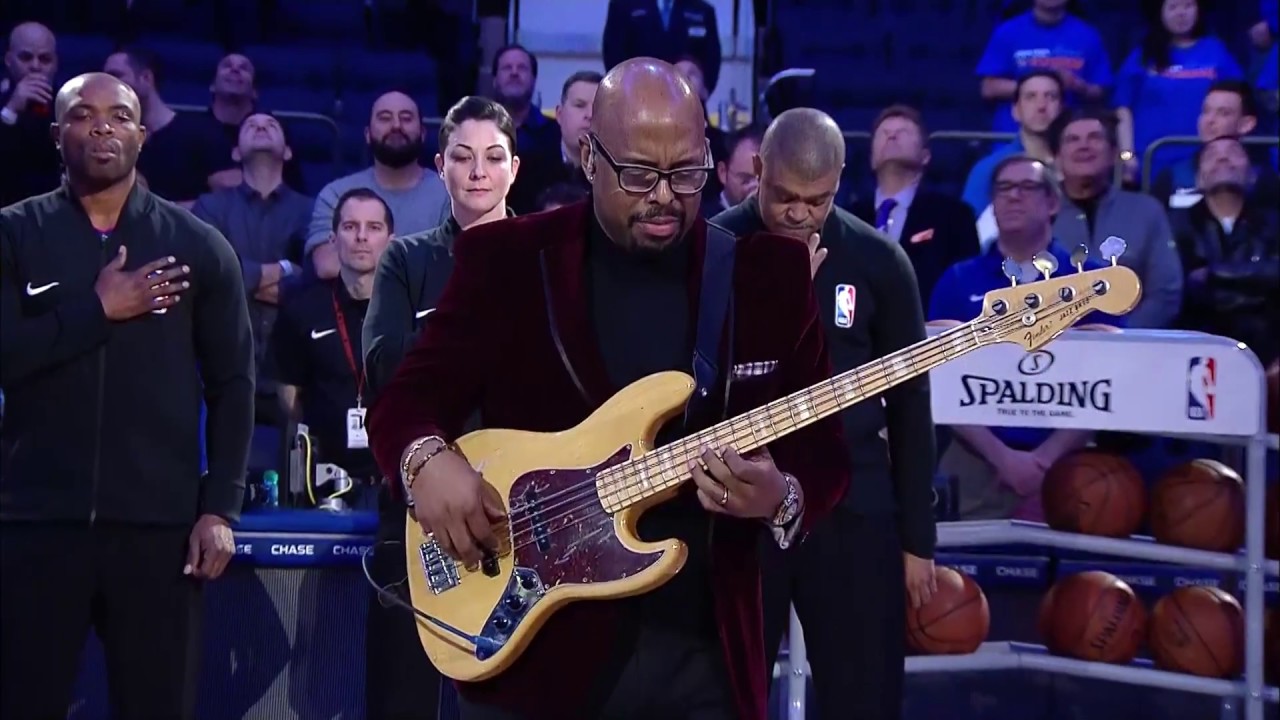

“Then, when I was at the end of my freshman year, I was 13, and I got my first Fender Jazz bass, and I was like, wow—this is how a bass guitar actually feels and plays! It’s like you learn to drive on a beat-up old Datsun or something, and then someone gives you a Ferrari to drive. They both have an engine and four wheels, but that’s about where the similarities end.“

I don’t want a student coming over to my house and seeing 20 or 30 basses there, and getting the idea that you need a huge number of bass guitars, because you don’t

What is your current electric bass of choice?

“I have a couple. There’s a luthier named Mas Hino who worked for Pensa-Suhr, who made a four-string maple neck fretless bass for me in 1997. That has been my main electric bass for a long time. In 2002 he moved to Japan and started working for Atelier-Z, where he made me a five-string maple neck fretted bass, like the sister bass of the four-string.

“Then in 2003, he made me a five-string maple neck fretless. Those basses made by Mas are my current basses, and I also have what I call a ‘Frankenstein’ Fender bass. It has an American body and a Japanese neck. The neck is from 1981; it’s maple. I just love maple necks—something about them hits the spot.

What aroused your interest in fretless bass – was it from Jaco Pastorius?

“Oh yeah, man! When I was growing up and listening to my dad practise, he was playing all these really out-there harmonics and ghost notes, and I asked him what he was doing, and he told me he was trying to learn a Jaco song. I asked him, who’s Jaco? And boy, did I ever find out.“

Have you ever considered a six-string bass?

“I’ve tried it, but that really is just too many strings. I got the lesson from when I played with the All-Star Big Band that Quincy Jones put together, on the Late Show With David Letterman – that was a great band.

“I was rehearsing with that band, playing my Pensa four-string bass, and Will Lee, who is the bass player in the Letterman band, was sitting across the studio and waving his hand and mouthing ‘Yes!’ at me, right through the rehearsal.

“When we had a break, I went over and asked him what he meant, and he said, ‘Man, every band that fetches up on here has a goddamned six-string bass, and I’m just so pleased to see a player with only four strings!’

Which other basses do you have?

“I have three acoustic basses and seven electric basses, which is not really a huge amount for a professional musician. I don’t want a student coming over to my house and seeing 20 or 30 basses there, and getting the idea that you need a huge number of bass guitars, because you don’t.“

I went through a phase... I had a custom-built pedalboard with a bass wah, a Big Muff, a delay, a phase shifter and a bass synth. I thought I was Bootsy Collins!

Do you like a pure tone, or do you enjoy effects?

“Years ago, I went through a phase that I think a lot of musicians go through. I had a custom-built pedalboard with a bass wah, a Big Muff, a delay, a phase shifter and a bass synth. It must have been about four feet wide and four feet long, and it weighed around 175 pounds. I thought I was Bootsy Collins! But that lasted for about a year, and like most guys do, I just went back to my natural tone, and about the only thing I bring along now is a synth pedal.“

Do you have instructions for sound engineers at your gigs?

“I do, yes. I’m in the fortunate position now that for my own shows with my bands, I can take my own soundman on the road with me, but when I’m working with other bands, then I like to ensure that I get the sound I want.

“I’m generally the most easy-going guy you will find, but I do believe that most sound engineers are not trained to mix sound for acoustic instruments. They’re used to hearing musical sounds that come out of an amplifier and a PA, and not the instrument itself, whether that’s a piano, or an acoustic bass, acoustic guitar or whatever.

“I think maybe they should get more training with classical players, so they would get used to how acoustic instruments sound naturally, and they can make them sound like they should. So, I have just one rule that I like to explain, which is, ‘Make my instrument sound like it sounds now’ – and that means not putting a lot onto it; no sound filtering.

“I use an amplifier, but I don’t like to use a huge amount of amplified sound, because I don’t like it loud. Keep the volume down, and let the natural sound come through as much as possible.

You played bass with Sting for two years; he’s a very accomplished bassist. Did he direct you, or let you find your own way?

“A lot of jazz musicians have a real thing about maintaining their own individual sound, and bringing their own creativity, and bringing in their own sound. I realized that I was not in Sting’s band to do that – it was not my role. My role was to play the bass-lines that Sting played on the record, and that was it.

“I had to earn his confidence, and earn his respect, and wait for him to say to me, ‘You don’t have to stick with the lines, you can stretch out a little bit, and bring your own influence in’.

“For most jazz musicians, if you ask them to do something different, they find that insulting. As a band leader I’m empathetic – I understand how to work with another band leader to get the best for the band’s sound. You don’t want this? No problem, what would you like? And that’s how to work things out. That way, I keep the gig.“

- Christian McBride's The Movement Revisited: A Musical Portrait Of Four Icons is out now via Mack Avenue.