Danny Elfman: “I’m not a shredder. My guitar on this album was the feedback and the messiness!”

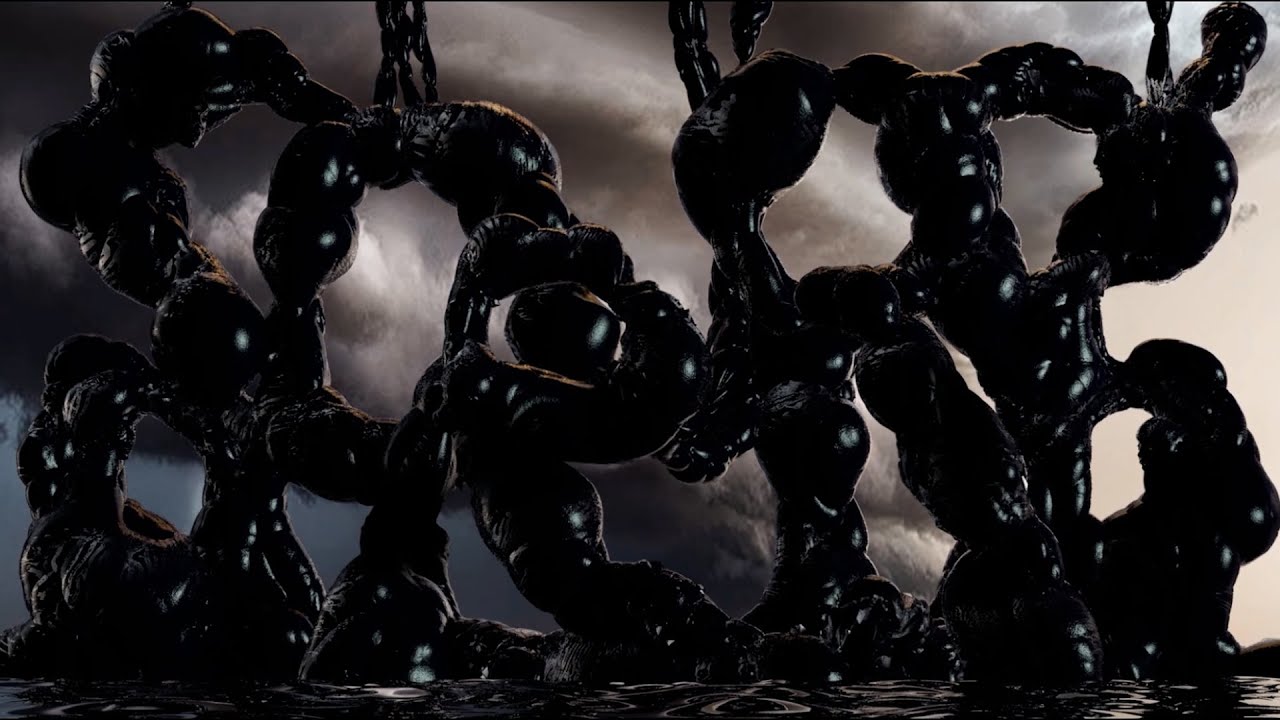

For his first solo album in decades, Big Mess, the composer grabs an electric guitar and takes a deep dive into his mid-pandemic psyche for a challenging ‘chamber punk’ metal sound

Besides learning that a microbe invisible to the naked eye could bring 21st-century civilization to its knees in a matter of weeks, the past year-and-a-half has taught us what we would do if only we were given the time.

As the social calendar emptied, people did all kinds of things. Some baked sourdough bread. Those of a literary persuasion set out to write the Great American Novel, or rather procrastinated until things opened up again. Maybe next time.

But many picked up the electric guitar and either learned to play it or finally found a use for it. Danny Elfman, the Grammy- and Emmy Award-winning Hollywood composer, was in the latter camp.

As he and his family were sheltering in place out of town, he had a guitar, a laptop, a Fractal Axe-Fx modeling unit and a whole bunch of ideas, that – not unlike a sourdough starter – began to take form once chemistry did its thing.

The resulting album, Big Mess, is his first solo effort since 1984’s So-Lo, and it recontextualizes the guitar within Elfman’s nine-to-five wheelhouse of synths and VST instrumentation, bringing onboard Nili Brosh and Robin Finck for a daring, sprawling release that, while being very much a record of our present moment, nonetheless feels juiced by the freewheeling spirit of '90s alternative and industrial rock, and augmented by orchestration.

Big Mess is quite the trip. It’s like 2020, the album, populated with anxious vignettes of discontent. How it fits in with Elfman’s oeuvre of film scoring is up for debate.

“I think it’s all mushed together in the overall cosmic sense of things, but I can’t say I have any sense of order of what it means,” admits Elfman. “You are probably better qualified to speak to that than I am.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

It’s not Jack Skellington playing Maynard James Keenan but it feels like there is some crossover. The macabre sensibility that has made his working relationship with Tim Burton so productive is writ large.

Those looking for a cinematic cultural reference point might find it plays a little like a Charlie Kaufman remake of Naked Lunch, or the Wachowskis directing Persona. But if there’s a visual it looks to plant in your head, or if there’s a story it’s telling, it’s one taken from within Elfman’s mind.

We are in an era when people go to Spotify and grab two songs and they don’t make it to the end of an album – I am kind of sorry for a generation who listens that way

Big Mess is also a change of pace. As Elfman notes here, he can play the guitar but he is not a guitar player. He arrives at it from a different perspective. Elfman used a custom-built thinline T-style from Reuben Cox’s Old Style Guitar Shop, in Silver Lake – one of three that was acquired from Cox.

With its fully hollow build, the Old Style thinline is super-lightweight, and is fitted with a Lollar Regal neck humbucker with a vintage '80s Seymour Duncan Hot Rails at the bridge. Elfman’s Fractal was his only outboard option. But then, what else do you need, besides time and space?

Here, Elfman talks about many things. How the fractious temperament of present-day America played an authorial role, keeping the vibe on edge. Why his long-standing relationship with Tim Burton works. The two similarly see the world from Dutch angles, seeing the morbid in the everyday. But Big Mess is very much the story of Elfman reconnecting with guitar.

Way back when, he really was a guitar player, playing new wave with Oingo Boingo, before he got his break in Hollywood and the phone kept ringing. There’s an element of isolation in scoring films, but Elfman in recent years has made performance a priority and taken great pleasure in doing so.

He was meant to play a ‘chamber punk’ set at Coachella 2020, culling works from his IMDb page to play with old Oingo Boingo tracks and have some fun in the process.

Then, well, that takes us back to the start, doesn’t it. Coachella 2020 got canceled. Fun got canceled. It was time to do something else. That’s where Elfman picks up the story...

Big Mess is provocative and challenging. Was it a conscious effort to resist this era of ambient content? Because it makes you sit in and listen.

“Yeah, I knew it was going to be very much out of sync with the times, because music in general is so ambient, and if it is challenging, it is a challenging lyric but still easy to listen to. There was a conversation about whether it was ridiculous to release this as a double album as opposed to holding one back, because there is so much.

“As I was writing the songs, they were coming out in pairs. I had a constant battle going on. [Laughs] They were coming out heavy, and they were coming out fast and crazy, and then heavy and serious, and then fast and ridiculous.

“That’s just the way I roll. By the time I had six songs I thought, ‘Okay, this is a Side A/Side B thing.’ I didn’t expect to end up with 18 songs. My manager said, ‘Why don’t we hold one disc back?’

“I said, ‘Because in a year or two, I’m not going to want to do any of this anymore.’ I know myself too well. Just risk it. If it catches on, it catches on. I know we are in an era when people go to Spotify and grab two songs, a playlist, and they don’t make it to the end, and I am kind of sorry for a generation who listens that way.

“When I grew up on albums, you took an album home, you put it on and it was a whole experience. You're going to get into that world and experience the journey. We are not wired that way any more.”

It feels like politics is getting more dangerous and art is getting safer.

“Yeah, definitely. I was just filled with so much venom that once I opened Pandora’s box there was just no stopping it. It surprised me but I felt like I had to get this shit out.

“2020 was a brutal year. On top of the pandemic, we were looking at a society just teetering on the edge of becoming a dystopian non-democracy, something that people had written about in stories for years but I never thought it was going to happen.

I wanted to be in a different band every two years, and every time I did anything, I wanted to do something in the opposite direction

“It was like the unimaginable is happening here, and a populist, crazy man becoming an idol – an idolized, almost worshipped figure! It’s incredible. Democracies are fragile things and people will hand it over. It was just a frightening time, but on the other hand, every time I would open up and vent, the other side of me is still sarcastic and ridiculous and it would elbow the other writer out of the way and let the song in.

“Y’know, this same sort of schizophrenia used to torture me when I was in a band, because I wanted to be in a different band every two years, and every time I did anything, I wanted to do something in the opposite direction. It was very frustrating because you just can’t do that easily in a band.”

Did that become easier when you became a composer?

“When I became a film composer, I found that very thing worked to my advantage, going from really heavy ping-pong extremes. You’d go from heavy action to a small, tiny, personal film then to a romantic film, then to sick and dark, then to ridiculous. You are able to zing from one extreme to another and that works well for me.

“What was interesting was starting to write songs, and I realized, yeah, that part – if anything – has grown even more extreme. [Laughs] There was no reconciliation at all. It was an interesting process. Again, I wasn’t expecting it.

“I was sitting down, literally to work on a commission for the National Youth Orchestra for Great Britain, for the Proms, which was meant to be last August [2020]. Then I realized that the Proms were never going to happen. And it just took the drive out of me.

“I am so deadline-driven with fucking everything! I said, ‘Well, I’ve got this one song…’ And I was already wired in my head for Coachella because I had spent three months on the show, and I had this new song I was going to premiere called Sorry.

“That was in my head; I was wired for guitars, and this concept of what I was calling at the time ‘chamber punk’ – the idea of a rock band and an orchestra playing together. Because of the Coachella thing, it got me in that frame of mind that it would be guitar-based rather than synth-based.”

The guitar has sometimes had a difficult relationship with synthetic instrumentation, perhaps simply because you’ve got something quite primitive pitched against something that can sound so futuristic. Where do you see the guitar fitting into all of this, with virtual instruments, synths, and so on?

“Yeah, it was difficult for me. The whole thing started with the song Sorry. I had written that the year before as an instrumental piece, and it was a concept piece that I was hoping to bring to a festival in Tasmania called Dark Mofo.

“That’s where I had this idea for guitar, percussion and orchestra, then that song – or that piece of music – was like a 10-minute instrumental, became a song for the album. But I still had that idea in my head of it still being centered around the guitar.

“It was hard for me because that’s what I was hearing. Guitars and strings, guitars and strings… When I sat down to do the album, I had my sample libraries, so I had my bass and drums, my strings, all in my computer, but I only had one microphone and one guitar. I wasn’t at my studio. And it was fine! ‘I’ll write an album. All I need is one hand-held mic and a guitar.’

“I didn’t need anything else except my computer to record into and then I’ll temporarily lay down my strings and drums which will get replaced by real strings and drums.

“I always heard it as centered around the guitar. Guitar and strings were driving me. That was the sound I had in my head. Usually when we arrangers use strings in songs, it’s more to add color and texture, but I was hearing the strings as part of the motor, as part of the rhythm section. That was the concept behind what became Big Mess.

“The last two songs I wrote for the album were by far the most mellow and probably the craziest, We Belong and Devil Take Away. Devil Take Away was a good example of just working around the guitar. I had a riff in my head and I decided, ‘I'm going to turn this riff into a rhythmic thing, as an improv, lay the vocal down and not go back and fix it.’

“It was really just like this being the first pass, laying it down and then not doing anything to it. That was the discipline for me. Don’t go back. Don’t fix it up… Don’t make it easier to play! [Laughs]

I did realize that without a deadline I was hopeless. I started in April, and then around July I said, ‘We’ve got to make some kind of deadline’

“Let it be ridiculous and over the top and don’t try to fix up the lyrics. They’re fine. That was combined with the song We Belong, which is the only orchestral ballad on the album. Once I did those two I thought, ‘That’s it, I’m done.’ [Laughs]”

Did you not feel as I did, mid-pandemic, that whatever you were doing you had to finish ASAP for fear you would die halfway through?

“There is also that.”

That is the ultimate deadline.

“That is the ultimate deadline. I wasn’t thinking about that. The thing that was weird for me was I was not thinking about a deadline and I had to make an arbitrary one. I wasn’t thinking so much about dying because I am always thinking about dying. [Laughs] I mean, it’s part of me!

“It’s like I have been feeling the grim reaper slashing his fucking thing over my head for the last 50 years, easily, and so that part of it wasn’t what I was concerned with. Also, I was holed away. I was really dug in.

“But I did realize that without a deadline I was hopeless. I started in April, and then around July I said, ‘We’ve got to make some kind of deadline.’ So by July/August, I said, ‘Let’s start playing it around.’”

This is a more personal work, more so perhaps than a film score because it’s coming out of nothing but your head.

“It’s very, very personal. And the other surprise for me when writing was that I was writing more first-person/personal than I used to. In the past, I used to do everything pretty sarcastically, and usually from a third-person perspective – from the standpoint of a character and not myself. That’s definitely one way to do it, but it is also protective.

“This may have been about the quarantine and isolation, but everything was really raw, and I found I was writing much more personal than I was used to, and it was kinda scary in a way but once I got used to getting it off my chest I thought, ‘What the fuck do I care?’ If they’re not into it, they’re not into it. And if they disagree, they disagree. I’m not going to worry about it.”

Because of your association with Tim Burton, it would feel like that's more in your natural register, but are some of your film scores more personal than others, and where do you see Big Mess in the context of that work?

“I don’t know. That’s something I don’t have a bead on. It’s something that I might have an opinion on a couple of years from now, y’know? This is all so, so new for me. I still don’t really know what it is I have done. It was pretty fast and my sense of what it is in terms of my own past is hard to say.

“Clearly, Tim Burton and I, the reason why we get along, is because we both have very dark sensibilities and a love of the macabre. But I am not sure if that plays into this so much. Y’know, when I first started scoring, the first big decision I made was not to let my songwriting influence my scoring. They are coming from two different places.”

What was your guitar setup like?

“It was really simple. It's a handmade guitar. There’s a little guitar shop just blocks away from my studio called Old Style, and [Reuben Cox] has made me three guitars and I really love it. The combination of pickups and stuff, I really love it; he’s just got a really good touch. It has a really light feel, which I like.

“For a long time, the guitar I played on stage was a really heavy guitar, beautiful, this Paul Reed Smith [Custom 24], but the one I grabbed when I went north to my out-of-town house, which was where I holed up for what I thought was going to be a couple of weeks and turned out to be a year, and so I grabbed of course a nice, light favorite.

We realized during the mixes that my guitars always kept it messy, and we wanted that

“This Old Style that I’ve got is, I mean, how to describe it? It’s this hollow-bodied electric, really light, and for someone like me, the fretboard and the action is very close and light.”

Sometimes it’s nice to have the guitar work with you…

“Especially for me. I’m not a guitarist. I’m not a shredder. For me, I don’t pick up the guitars for years and then I’ll suddenly pick one up.”

You didn’t take much else with you, right?

“I was so ill-equipped to record an album up there, because it is not a studio. It’s just a little writing room, and I didn’t even have a pair of headphones that worked. [Laughs] Because, when you’re scoring, you don’t need headphones. I have them but I just never use them, and when I started recording it was like, ‘Shit, my headphones aren’t working.’

“I had this little black-and-white Old Style, and one mic, and that was it. I did everything, the demos for the songs. Out of those demos, half of the demo guitar [tracks] survived at least into the final mixes because Robin and Nili came in and they’re both great, but the thing we realized during the mixes was that my guitars always kept it messy, and we wanted that.

“In other words, if we play, Robin and Nili are great, and when you put me in it, it messes it up. [Laughs] That was kind of the sound I wanted. My guitar was the feedback and the messiness, and that all came out of me, and all of my vocals were recorded on this little handheld mic up in this room.”

And you used those in the final recording? That’s cool.

“I kept all the vocals from the demo recording. I didn’t redo anything. I didn’t want to ‘get it right’. It was part of the approach to this album. Because I’m used to, in the old days, you do the demo and then you get into the studio in front of a really nice old mic and you’ll do 10 maybe 12 takes and you’ll pick the verse from this and the chorus from that. But I just didn’t want to do it that way.

“I actually learned this from The Nightmare Before Christmas – a quarter-century-plus ago. Tim Burton and I went into the studio to record all 10 songs as demos for the director, Henry Selick. Except Sally’s Song, on which I brought in a female singer to sing, I did all the voices, big, little, harmonies – Oogie Boogie, Jack Skellington, everybody – and they were just demos. We sent them up north and it was like, ‘Okay, these are the songs.’

“A year later, I'm back in the studio. Okay, now we've got to record these vocals for real, and Tim would be in the booth, and I'm in this record studio, thinking, ‘Yeah, this is sounding pretty good.’

“And Tim was like, ‘I know this sounds crazy, but can we listen to the demo?’ We put the demo on and he was like, ‘I hate to say it, that verse and this chorus, this part too, they sound better on the demo.’ I listened to it and was like, ‘You’re right, they do.’ Half of those demo vocals made it into the movie, and it was an important lesson for me: never underestimate your first approach to something.

Me and my tattoo artist quarantined and had a marathon for two, three days straight, and I couldn’t have down it without Tool's Fear Inoculum!

“For this, I mean, there are definitely some vocals where I did more than one pass. I tried different approaches – because I was still trying to figure out my voice. But once I laid it down, if it feels right, I'm not going to fix it. If it’s a little out of tune, I don’t care. If it’s a little funky, it is what it is.

“I know that I could spend days and days in the studio and I could get everything technically better but that won’t make it better on this album, for this kind of thing.”

It’s like you were talking about earlier, ‘chamber punk’ – you don’t want it to be safe, to be perfect. Maybe that’s why you and Tim have such a good working relationship. You can make things perfect but take the life out of it.

“Definitely. That is something that Tim and I have always been very in-sync on. He never deconstructs. When we're talking about a movie, he never deconstructs it, gets into the back story and breaks it down; he just tells me how he feels.

“He makes it how he feels, and, definitely, when it comes to my music, I don’t have to worry about not achieving perfection… Because I never achieve perfection! [Laughs] It is simply not gonna happen with me!

“I've never heard Tim saying anything more complimentary about his own work than 'I think I did okay. I think it came out okay.' And that’s kind of how I feel with my own work. I get to that point and I think it’s okay. I don’t really know. It’s okay.”

Okay is perfect. Big Mess is also kind of metal. What’s going on there?

“I think that’s just where my tastes have gone in the last three decades. More and more, I tend to like extremes. Like everything else! I either want to hear something strangely beautiful and abstract, atmospheric, or really intense, that just grabs me and holds me. I am a big fan of [Einstürzende] Neubauten, over in Berlin. Even though I can’t say their name properly I love their music.

“I love Tool. I love Nine Inch Nails. I couldn’t have gotten round to finishing a 35-year-old tattoo last year – that’s another thing I did during quarantine. Literally, I started a [tattoo] project 34 years ago and never finished it, and so me and the tattoo artist quarantined and had a marathon for two, three days straight, and I couldn’t have down it without Fear Inoculum. [Laughs]

“That Tool album in my earbuds, turned up as loud as I could bear it, was was the only thing that got me through those sessions. It was fuckin’ torture!”

- Big Mess is out now via Anti-/Epitaph.

Jonathan Horsley has been writing about guitars since 2005, playing them since 1990, and regularly contributes to publications including Guitar World, MusicRadar and Total Guitar. He uses Jazz III nylon picks, 10s during the week, 9s at the weekend, and shamefully still struggles with rhythm figure one of Van Halen’s Panama.