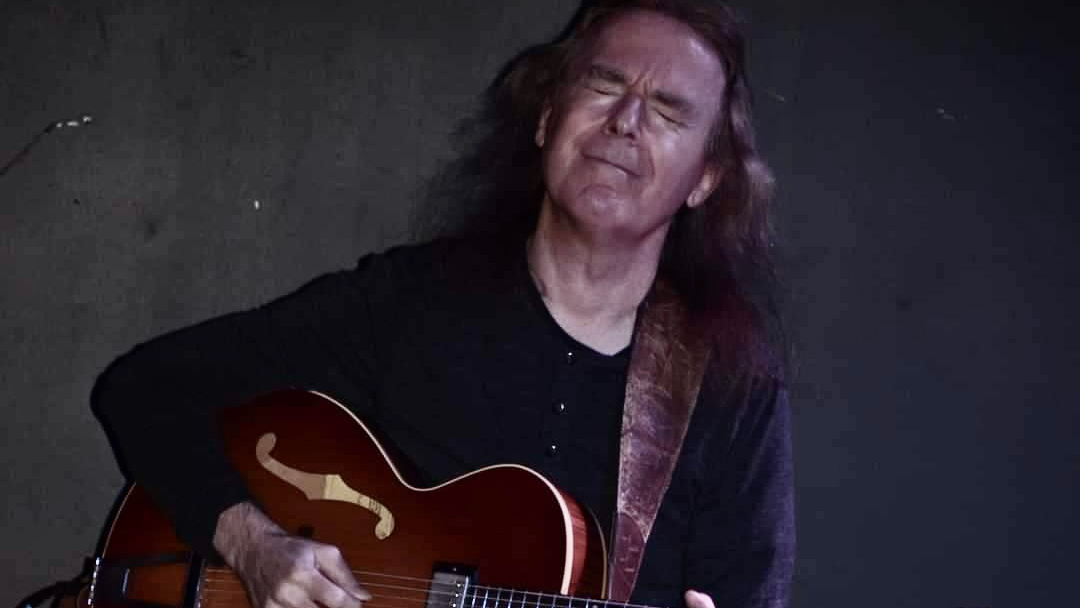

“When people say ‘jazz’, they get locked into ‘It's not this; it's this.’ I never looked at music that way”: Grammy-nominated virtuoso David Becker is nurturing the future of jazz guitar – and he’s encouraging them to break the rules

With two signature guitars to his name and multiple Grammy and Emmy nominations, Becker has notched up some serious accolades over four decades in the biz. He shares the secret to a long career – and explains how social media is (and isn’t) shaping the future of jazz guitar

Recognized as a world-class jazz guitarist, but well versed in every genre, Grammy- and Emmy-nominated David Becker has recorded 20 albums. Included in that catalog is 2005’s acclaimed The Color of Sound, a duo project with beloved instructor and friend, the late Joe Diorio, whom he met while studying at GIT.

Becker’s Heritage signature guitar was introduced at the 2015 Winter NAMM Show. Known as the “Million Miler” because of its travel history, it remains his touring and onstage companion. In 2020, Homestead Guitars debuted his signature acoustic. Last year, Sheptone announced the David Becker Signature Strings Set.

His latest release is Planets, released last year. He has also performed on countless sessions, authored instructional books, recorded educational DVDs, and held masterclasses and workshops. He spends much of his time on tour in the U.S. and abroad with his band, the David Becker Tribune.

You are coming up on 40 years as a professional musician. To what do you credit your longevity?

“It’s hard to believe it’s 40 years. I think it’s about staying relevant and always trying to grow, because as a musician, you want to constantly get better. I'm fortunate to have a big catalog of music and that I can keep touring. The thing I try to do is challenge myself, see where there are places I haven't played, and investigate opportunities. Other things come into play as well, things you didn't anticipate, and somehow things move forward.”

When you hold workshops, in addition to technique tips, what do attendees want to know? What is your key piece of advice?

“When young musicians ask, 'How do I build a career?' the main thing I say is, 'You have to have a goal of what you want to do.' If you don't know what you want, it's very difficult to work towards something. What I tell people in workshops is, get a clear picture in your mind, as best you can, of where you see yourself. Every day, when you get up, meditate and imagine yourself doing it and what it feels like.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“The other thing I tell them is, don't define success as the number of records you sell, or the number of concerts you do, or how much money you make. Success is completing something. If you start a project, complete it. If your goal is to write a song, learn a solo, do a gig, make a record, release the record, whatever it is, do it. That way, there are always things you can look at and say, 'I achieved that.'

“The next step is to do something else and keep going towards whatever you want to achieve. Everything else is out of our hands. But if you continue completing things, that will manifest itself into what we call success.”

It's so easy to beat ourselves up and say, “That didn't happen. I failed,” whereas you look at incremental goals as individual successes. How did you develop that mindset?

“To start with, a lot of people are not afraid of failure. They're afraid of success. Meaning, when they get the opportunity to do something, they shoot themselves in the foot because they're afraid of having to deliver the goods. It's like they get a chance to do this and they run away from it.

“I was pretty lucky because I started off with the idea of what I wanted to do. As a teenager, I played trumpet before I played guitar, and I was really good. When I started playing guitar, my teacher said to me, 'You know you're going to play music,' and I said, 'Yeah.' I wanted to be a jazz guitar player, make records, tour, and have my brother in the band. That idea manifested itself when I was 17 or 18.

As years go on, obviously there are peaks and valleys in everybody's career. You just have to maintain the attitude that 'I'm going to keep working and doing what I have to do to continue to be here'

“I knew there was a lot of work involved. I knew you always had to do things to get there. But once you got there, that wasn't the end. For instance, when I got a record deal with MCA, which I never imagined in my wildest dreams, I knew that wasn't the end-all goal. That was the next step to, 'Now I have to go out there and play and do the next thing.'

“I think it was having that experience at a young age and being around a lot of people who encouraged that attitude, like Joe Diorio. He always told me, 'David, don't go for the money. Go for the music. Go for what you believe in. Everything will work itself out if you just have that goal.'

“As years go on, obviously there are peaks and valleys in everybody's career. You just have to maintain the attitude that 'I'm going to keep working and doing what I have to do to continue to be here.' It's not about trying to achieve that ultimate success of 'There you are. Now what do you do?' If that’s it, you might as well give up. So always having a goal is a big part of it.”

You came to these realizations during a very different time. Today there is a lot of emphasis on being TikTok and Instagram famous. What are your thoughts?

“It's different, yet it's the same. Now you can instantaneously reach people around the world, whereas when I started, we had to physically go to Berlin or Munich to play, which we did. Our first tour was in 1984. I was 22, we went to Germany, and all I had was an EP from Warner Brothers.

“Today we have all these supposedly magical tools, but you still have to do the work. If all you want is to be famous on YouTube, there are things you can do, but I don’t recommend it. What’s the point? Is it instant fame you want, or do you want to maintain something? Obviously there are people who have had careers through YouTube or whatever, but you still have to deliver the goods.

I've produced a lot of demos for young musicians, and when I ask, 'What do you want to do with this?' a lot of them don't know

“I've produced a lot of demos for young musicians, and when I ask, 'What do you want to do with this?' a lot of them don't know. You have to find a way to make the most out of it. It may only be a small piece, but every piece of that puzzle is important, because if one's missing, you won’t have the full picture.

“You have to use all those tools – Instagram, Facebook, YouTube, whatever media you have available to you. Figure out the best way to use them for you, but don’t think it's instantaneously going to happen because you've got 45,000 views and now you’re going to be a star. That's not what it's about. You have to work on yourself and figure out, 'How do I do this?' because when you get all that stuff out of the picture and you stand in front of an audience, that's ultimately what's going to count. That's what’s really important.

“A lot of people on these forums don't have a specific goal other than becoming famous. If that’s all you want, you can have your five minutes of fame and then do something else. But if you really want to build a career for life, utilize those tools to the fullest, but realize there are other elements you need too. You have to work on your musicianship. You have to work on all these other things that are important.”

When we say “jazz guitar” in 2023, it can mean many things. What do you see when you look at the genre?

“It's funny, because I don't pay too much attention to the scene. I just focus on what I'm doing. But I do get little glimpses of it, and there are many really talented young guitar players out there. I see them all the time at music schools.

“But what you'll find – I had this conversation with Joe Diorio until he passed away, and I’ve talked to Pat Metheny and other guys about it – is that it’s easy to find a kid who's 22 or 21, or maybe even 18, who sounds like Jim Hall, and that’s fine. It’s good to do that and understand that. But at some point you have to say, 'Who am I and what do I do?' That takes time to develop.

I know it’s hip to play in a certain style or time period and stay true to that, which is cool. But, for me, it's like, if you were born in, let’s say, 2001, why not incorporate some of the elements you grew up with?

“Also, when people say 'jazz', they get locked into 'It's not this; it's this.' I never looked at music that way. I was lucky to grow up with parents who listened to classical music and big band, and my oldest brother bought Led Zeppelin and Jimi Hendrix records. I never put things into a style. I just liked music. There was a period, when I was studying at GIT, when I became a jazz snob and closed my view of things for a while, but I opened it back up and rediscovered a lot of great things.

“I know it’s hip to play in a certain style or time period and stay true to that, which is cool. But, for me, it's like, if you were born in, let’s say, 2001, why not incorporate some of the elements you grew up with? That's what musicians have done over the years. They live in their time, but they look back at the traditions of the instrument and the music as well as forward.

“For example, I love playing All the Things You Are and Stella by Starlight, but that's not all I want to do. I still learn a great deal from that, but I want to add my two cents to the fold, if I can.”

- For more information, head to DavidBeckerTribune.com.

Alison Richter is a seasoned journalist who interviews musicians, producers, engineers, and other industry professionals, and covers mental health issues for GuitarWorld.com. Writing credits include a wide range of publications, including GuitarWorld.com, MusicRadar.com, Bass Player, TNAG Connoisseur, Reverb, Music Industry News, Acoustic, Drummer, Guitar.com, Gearphoria, She Shreds, Guitar Girl, and Collectible Guitar.