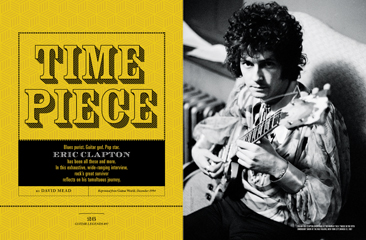

Eric Clapton: Time Pieces

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Blues purist. Guitar god. Pop star. Eric Clapton has been all these and more. In this exhaustive, wide- ranging interview, rock’s great survivor reflects on his tumultuous journey.

In 1994, after 30 years in the business as a blues-influenced rock and roll electric guitarist, Eric Clapton finally got down to the business of recording a blues album of his own. From the Cradle was a far cry from the fast-and-loose style of blues tribute tossed off by less-reverent players; it was a collection of authentic blues songs played on instruments from the period and constructed with the loving care of a man who has a reputation for nitpicking perfection in everything he does. Ironically, the album was recorded in the very studio where, as a member of the British group the Yardbirds, Clapton had cut the band’s first single, “I Wish You Would.” Located in London, England, Olympic Studios has been the site of numerous recordings he has made throughout his long career. The studio made the perfect setting for Clapton to reflect upon his past and discuss the guitarists whose work is at the heart of his own.

ERIC CLAPTON I’m recording this album as much as I can with everybody on the floor at the same time—horns and everything. We’re trying not to overdub anything at all, so mistakes and everything go in.

GUITAR WORLD A bit like the old Chicago days?

CLAPTON Yes, I suppose so—although I think even they overdubbed sometimes. But for the purpose of getting it the way I want it to feel, I want everything live.

GW In a way, this studio is your old stomping ground, isn’t it?

CLAPTON This is where a lot of the early stuff was done. This is my idea of a recording studio; I came here more than anywhere else, and it’s between where I was born and where I used to hang out. It’s in the middle of all of my stomping grounds, and I think I must have recorded here with just about every outfit I ever played with—although I don’t think John Mayall came here.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

GW Can you remember what it was that turned you on to music in the beginning?

CLAPTON Well, the first thing that rang in my head was black music—all black records that were R&B or blues oriented. I remember hearing Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee, Big Bill Broonzy, Chuck Berry and Bo Diddley, and not really knowing anything about the geography or culture of the music. But for some reason it did something to me—it resonated. Then I found out later that they were black; they were from the deep South and they were American black men. That started my education.

In fact, the only education I ever really had was finding out about the blues. I took a kind of elementary, fundamental education in art, but it didn’t rivet my attention in the same way as blues did. I mean, I wanted to know everything.

I spent all of my mid-to-late teens and early twenties studying the music; studying the geography of it, the chronology of it. The roots, the different regional influences and how everybody interrelated and how long people lived and how quickly they learned things and how many songs they had of their own and what songs were shared around. I mean, I was just into it, you know? I was learning to play it, as well, and trying to figure out how to apply it to my life. I don’t think I took it that seriously as a potential profession, because when you’re young, you don’t; it was only when other people showed an interest that I realized that I could make a living out of it.

GW What about your choice of instrument? When did you first hear the guitar and think, That’s what I want to play?

CLAPTON I think that when I heard early Elvis records and Buddy Holly—when it became clear to me that I was hearing an electric guitar— then I think I wanted to get near it. I was interested in the white rock and rollers until I heard Freddie King; then I was over the moon! I knew that was where I belonged, finally. That was serious, proper guitar playing, and I haven’t changed my mind ever since. I still listen to his music in my car, when I’m at home, and I get the same boost from it that I did then.

GW The first guitar of yours was a Hoyer, wasn’t it?

CLAPTON Yeah, it was a Hoyer acoustic.

GW Did it have nylon strings or metal?

CLAPTON Funnily enough, it looked like a gut-stringed guitar, but it was steel-stringed. An odd combination.

GW But it wasn’t too long before you got your first electric?

CLAPTON I got a Kay doublecutaway. I got one because Alexis Korner had one.

GW That can’t have lasted too long either, because by the time you were in the Yardbirds, you were using Telecasters and Gretsches.

CLAPTON It didn’t stand up too well. I think the neck bowed, and it didn’t seem to me that you could do much about it. It had a truss rod, but it wasn’t that effective, and the action ended up being incredibly high. I remember at some point I didn’t want it to look like it looked any more, and so I covered it in black Fablon [vinyl adhesive shelf paper]! Can you imagine what it sounded like after that? Let alone what it looked like?

I ended up with the ES - 335TD C and then I got into Fenders. I had a Telecaster and a Jazzmaster.

GW What was it like for you when you started playing in the clubs?

CLAPTON Well, anybody that had any idea of how to play any instrument could just about hold their own, because there was no competition—there was no one around. There was only a handful of bands, and anyone that could play Sam and Dave, Stax and Motown was a master. I came from the blues, and so I had a grasp of that kind of thing; to my reckoning, R&B came from the blues, so I felt I was in some kind of inner sanctum, mentally or spiritually or whatever. If you could play anything in a halfway convincing fashion, you were the boss. If you were pretty good, you could work all the time and you’d get fairly well paid and be successful. It was easy to be successful if you had what was necessary, which was the right musical taste.

GW It’s a historical fact that, in the early part of the Sixties, it was practically impossible to get the electric guitar sounds heard on blues records using Britishmade amps. How did you overcome that?

CLAPTON Just by turning them flat out! I though the obvious solution was to get an amp and play it as loud as it would go, until it was just about to burst. When I was doing that album with John Mayall, it was obvious that if you miked the amp too close, it would sound awful. So you had to put the mic a long way away and get the room sound of that amp breaking up.

GW That was when you discovered Marshalls, wasn’t it?

CLAPTON Yes.

GW What were you using prior to joining the Bluesbreakers?

CLAPTON I was using Vox AC30s and things like that, but they didn’t do it for me. They were too “toppy”; they didn’t have any midrange at all.

GW Did you use anything to drive the front end, or did you just crank them right up?

CLAPTON Cranked them right up and still they didn’t distort, as far as I can remember. They may have distorted, but I can’t remember that they did so in an attractive way. It didn’t really get thick; it just got edgy.

GW Did you harbor any romantic feelings for that period at all? I think it was Mark Knopfler who said that in some ways he misses the old days, where you could show up at a club with an amp and a guitar and just do a gig.

CLAPTON Well, yeah, that’s true. Although I don’t picture myself doing that these days. It’s funny for me now to think of walking into a club and seeing another band play. I do it every now and then and it all comes back to me, and I feel like this is where I belong. I mean, I grew up playing in clubs; that is my spiritual stomping ground. And every time I walk into a club, I feel like I’m going to be asked to play, but I don’t get asked to play.

Back in the Sixties, if you did go into a club to see someone play, you already knew those people; there was no intimidation, no inhibitions at all. It was just that you hung out with these people and you played with them all the time, so in that respect I miss that camaraderie. There was competition, but it was friendly; now I think it’s much more aggressive. I went through that [being a] “dinosaur” thing 10 years ago, so God knows what it’s like for me to show up somewhere now! I don’t know what they think of me now if I walk into a club. What do I represent to young players? I have no idea. I don’t know where they’ve gone in their heads now, what they think, what their influences are. It probably has nothing to do with what my contribution was. I have no idea.

GW Let’s talk about the whole “Clapton is God” thing. Were you uncomfortable with it?

CLAPTON I thought it was quite justified, to be honest with you! [laughs] I suppose I felt that I deserved it for the amount of seriousness that I’d put into it. I was so deadly serious about what I was doing. I thought everyone else was either in it just to be on Top of the Pops or to score girls or for some dodgy reason. I was in it to save the fucking world! I wanted to tell the world about blues and to get it right. Even then I thought that I was on some kind of mission, so in a way I thought, Yes, I am God; quite right. My head was huge! I was unbearably arrogant and not a fun person to be around most of the time, because I was just so superior and very judgmental. I didn’t have any time for anything that didn’t fit into my pattern or scheme of things.

GW Before that time, you’d actually played with Muddy Waters. How did that come about?

CLAPTON I think Mike Vernon [the producer of Blues Breakers with Eric Clapton] put the whole thing together. He got Muddy in the studio, and all I can remember is just being incredibly scared, clumsy and overwhelmed, you know? Completely overwhelmed. At that time, the blues thing was going through some funny changes; if you played electric guitar, you’d sold out. Josh White had done a lot of touring in Europe, and Big Bill Broonzy had, too. Josh would go on and do “Down by the Riverside” and “Scarlet Ribbons” and things; it was very middle-of-the-road blues and folk, and it was all acoustic.

Then Brownie McGhee and Sonny Terry would tour and they made it palatable; they kind of acquainted everyone with the blues via the acoustic guitar, and so I think when Muddy came over the first time, he brought an electric guitar and it wasn’t very well received. So he wasn’t everybody’s cup of tea. It was only the purists who knew about Chicago blues.

GW It must have been an overwhelming thing for you to play with him, since you were only about 20 at the time.

CLAPTON Yeah, if that. I couldn’t take it all in. I felt really stupid because I was a little boy trying to play a man’s music, and these were the men. They were actually just past their prime, so they’d done it; they’d done what I’m still trying to do. I felt really clumsy. I thought I didn’t really belong, but I felt very grateful for the opportunity.

GW Everybody assumes you were with the Yardbirds a long time or that you were with the Bluesbreakers a long time, but in actual fact it was a matter of months in both cases.

CLAPTON Yes, I went through all those things very quickly. I mean, Cream was like a year and a half or something, and even with John Mayall, I was only half there. I was so unreliable, so irresponsible. I would sometimes just not show up at gigs, and that’s how Peter Green would be asked to play—because I was not there. I went to see John last year to actually make amends. I’d been looking back and realized how badly I’d behaved.

GW How does Cream fit into your perspective now? It must have been a very intense 19 months.

CLAPTON It was very intense; it actually seems like we were together for three or four years, but in fact it was very short. I think my overall feeling about it now is that it was a glorious mistake. I had a completely different idea of what it would be before I started it, and it ended up being a wonderful thing, but nothing like it was meant to be.

GW It was meant to be your band, wasn’t it?

CLAPTON It was meant to be a blues trio. I just didn’t have the assertiveness to take control. Jack [Bruce] and Ginger [Baker] were the powerful, dominant personalities in the band; they sort of ran the show and I just played. I just went with the flow in the end and I enjoyed it greatly, but it wasn’t anything like I expected it to be at all.

GW In the Cream period, you virtually ran the gamut of Gibsons. You played a Firebird, a 335, Les Pauls, the very famous psychedelic SG. Were there any particular favorites? Apparently, you’ve still got your 335.

CLAPTON Still got that 335, and I love it. I still get it out every now and then. The 335 was a big favorite, and that particular Firebird— I had some great times on that. The single pickup was a fantastic sound. I think that SG went through the Cream thing just about the longest. It was really a very, very powerful and comfortable instrument because of its lightness and the width and the flatness of the neck. It had a lot going for it—it had the humbuckers; it had everything I wanted at that point.

GW You’ve played as a guest on many different albums, but the most unusual must be your contribution to Frank Zappa’s We’re Only in It for the Money.

CLAPTON Yeah, we were pals. It started when I went to New York with the Cream and the Who to do the Murray the K show [Murray the K was a famous New York City disc jockey during the Sixties]. We used to go down to the Village to find out what was going on; there were the Fugs and the Mothers [of Invention, Zappa’s band], and you’d be able to go into the Café Au Go Go and see B.B. King play and just everything. New York was unbelieveable. The Mothers were at the Garrick Theater, and there would be nobody in the audience—nobody! They were experimenting every night; they’d have odd people, bag ladies and marines, on the stage, and Frank would come off and sit in the audience and talk to someone while the band played. It was madness! He took me home one night to his house and he made me play into a Revox [tape recorder] and told me to play all the licks I knew. I thought it was really sweet, and I didn’t mind doing it. I was just really flattered that he was interested, because it was clear this was a musical intellectual I was meeting.

He was very manipulative and knew how to appeal to my ego and my vanity, and I put everything on this tape. I think he just had files and files of tapes of people, and I was in there somewhere. When I went back I called him up and he invited me to the studio. He’d already had someone inside a piano talking—he’d climbed inside the piano—and he said, “I want you to pretend to be Eric Burdon [the Animals’ lead singer] on acid.” And that’s what I did. I was just saying, “I can see God,” and all this stuff, and it was funny to be involved with these people. I felt like I was being incredibly hip and fashionable… God, I had some funny times with Frank.

Another time I went to L.A., and I knew he was having a party, so I went ’round to his house and someone opened the door and put a guitar in my hands. It was already plugged in, like they’d been tipped off that I was coming, and I walked straight into this trap. Another time, I went to see him in concert, and he invited me to play. When I went out to do my solo, he did that famous thing of doing hand signals to the band, and they went through about 10 different time signatures and fucked me up completely! I couldn’t make head or tail of it.

GW Looking back now, are you able to put your history into context objectively? Are you able to look back at the player you were then and actually think, Yeah, that was okay, or, That was a bit shaky?

CLAPTON Yes, fairly. I think all of it was okay until drugs and drink got involved. I don’t think my facility as a player has really gotten much better or worse. I mean, I just finished doing a blues in there, a Freddie King song, and it doesn’t sound that much stiffer or that much faster than when I was with John Mayall or Cream— a bit more fluent, a bit more confident maybe. But what’s clear to me is that then I was much more in touch with the actual making of music, as I am again now. There was this long bit in between where I was more inclined to just get out of it. At some point toward the end of the Sixties and all the way through the Seventies, I was out, you know? I was on holiday, and being a musician was my way of making the money to be on holiday.

GW That whole thing started with Jimi Hendrix’s death, in a way. The dates are almost coincidental, aren’t they?

CLAPTON Yeah. It was funny how that all picked up. The Sixties were great and we were all doing drugs recreationally. We were all under the impression that we could take it or leave it. It was more like weekend binging: you’d do whatever you were doing, and then you’d get stoned one night or you’d take acid, and then you wouldn’t do it again for a while. Then it got to the point where those of us who were addicts by nature just carried on doing it, and we’d do it all the time.

I think we lost the thread then, but—and I suppose this may be a bit presumptuous—it kind of opened the door for punk, because there was no continuity from the musical pattern that evolved in the Sixties. It kind of got scrambled and lost with all the drugs and opened the door for all the anarchy, bitterness and anger. The musicians of the Seventies didn’t really have a very clear legacy. The legacy got very fucked and very self-indulgent. I think that the whole thing about the Sex Pistols was that there were really pissed off at our indulgence—the indulgence and that self-righteous stance of the Sixties.

GW Jimi actually jammed with Cream, didn’t he?

CLAPTON Yes. First time I ever met him, we were playing at the Central London Polytechnic, and Jimi came along with [his manager] Chas Chandler. I don’t know how long he’d been in England, maybe a couple of days, but he got up and played. He was doing Howlin’ Wolf songs, and I couldn’t believe this guy. I couldn’t believe it. Part of me wanted to run away and say, “Oh, now this is what I want to be—I can’t handle this.” And part of me just fell in love. It was a really difficult thing for me to deal with, but I just had to surrender and say, “This is fantastic.”

GW You became good friends, didn’t you?

CLAPTON Oh yeah, instantly, instantly.

GW I don’t think people realize how much of a blues player Hendrix was. In a lot of ways it’s obvious now, but in those days it didn’t seem to come into it.

CLAPTON No, I know. I think a lot of people thought, Oh yeah, the Band of Gypsys thing was the best. Or they look at different eras of his music making in terms of his “peak” or his “most prolific” or his “most creative” periods. But the core of all his playing was blues, and what really used to upset him the most was that he got this fixation about selling out. He got very down on himself and very cynical about his acceptance. He thought he was going commercial all the time, and yet he couldn’t stop himself, in a way.

GW You’ve recorded Jimi’s “Stone Free” and “Little Wing” in the past. Why haven’t you recorded more of his songs, seeing as you were so close?

CLAPTON I got very jealous of Jimi. I was very possessive about him when he was alive, and when he died I was very angry and got even more possessive. If people talked to me about Hendrix, I would just turn away; I wasn’t interested in their perception of Hendrix because I felt like they were talking about an ex-girlfriend or a brother who had died. I just thought, I’m not talking to you about it; I knew him and he was very dear to me, and it’s very painful to hear you talk about him as if you knew him—you fucking didn’t!

I didn’t want anything to do with it. It’s taken me all of this time to heal. I don’t know how long the grieving process is, but in my experience, it’s a fucking long time. It’s taken me this long to be able to pick up a guitar and play a Hendrix song.

GW Why did you choose to record “Stone Free” for the 1993 Hendrix tribute album, Stone Free?

CLAPTON Well, the thing with “Stone Free” is that when Jimi first played it to me, he told me that it was the one he wanted as the A-side instead of “Hey Joe.” To me, it was better than “Hey Joe.” When I heard “Stone Free,” it blew my fucking mind! And I thought, They’re going to put “Hey Joe” out because it’s commercial, but he wanted “Stone Free.” And it was the first recorded thing that I’d heard of his, and so that was the connection to our friendship.

GW Was your switching to Strats around the time of Jimi’s death a conscious tribute to him on your part?

CLAPTON Yes, I think it was. Once he wasn’t there any more, I felt like there was room to pick it up. Then I saw Steve Winwood playing one, and something about that really did it for me. I’d always worshipped Steve, and whenever he made a move, I would be right on it. I gave great weight to his decisions, because to me he was one of the few people in England who had his finger on some kind of universal musical pulse. I went to see him at the Marquee, and he was playing a white-necked Strat, and there was something about it…

GW When did you start playing slide?

CLAPTON I’ve always played slide—not electric—but I played slide when I was playing acoustic in the pubs. I tried to play like Furry Lewis and the more primitive rural blues musicians, and I also tried to be a little bit like Muddy. Then it sort of went to one side, but it’s always come and gone; I’ve never really stuck very hard at it. I do love it, but somehow or another it doesn’t have the madness. When I got into Buddy Guy, there was something about the madness of his playing that I fell in love with. It was like someone jabbing you with their forefinger. It was the staccato madness of it, which you can’t do on slide.

GW Was Duane Allman an influence on your slide playing?

CLAPTON Yes, very much so.

GW The story of your meeting has it that you just went to see him in concert.

CLAPTON Well, we’d started the Derek and the Dominos album and we hadn’t really got very far. I’d written some songs and we had played gigs—some touring in England—and we’d got a kind of persona. But in the studio, it was very one-dimensional, and it didn’t feel like we were getting anywhere. There was a bit of frustration in the air. [Producer] Tom Dowd has always been a very clever mixer of people; he’s always been a great one for being a catalyst and putting different combinations of musicians together to get an effect. I don’t know whether he saw an end result or not, but I think he just wanted me to see Duane. In fact, I’d been talking about Duane, because I’d heard him play on Wilson Pickett’s recording of “Hey Jude,” and I kept asking people who he was. So Tom took me and all the rest of the Dominos to see the Allman Brothers play in Coconut Grove and introduced us.

I said, “Let’s hang out. Come back to the studio.” I wanted Duane to hear what we’d done. We just jammed and hung out, got drunk and did a few drugs. He just came in the studio and I kept him there! I kept thinking up ways to keep him in the room: “We could do this. Do you know this one?” Of course he knew everything that I would say, and we’d just do it. A lot of those things, like “Key to the Highway” or “Nobody Knows You When You’re Down and Out” are first or second takes. Then I’d quickly think of something else to keep him there. I knew that sooner or later he was going to go back to the Allmans, but I wanted to steal him! I tried, and he actually came on a few gigs, too. But then he had to say, almost like a woman, “Well, you know, I am actually married to this band and I can’t stay with you.” I was really quite heartbroken! I’d got really used to him, and after that I felt like I had to have another guitar player. I had Neal Schon come in for a little while, having met him through Carlos Santana, but by that time we were getting really fucked up and the band was on its way out.

GW That was the beginning of your dark period, wasn’t it?

CLAPTON I don’t know whether it can be fairly placed at the door of drugs or relationships or life issues as much as I just had to get away. I had been doing so much. I’d been out there for a long time, playing and playing, with no break. I do that a lot; I work quite hard—I always have. And at that point, for some reason, a combination of things put me into a kind of retirement that I needed.

I remember at the end of that period that I was starting to fall back in love with music. I remember listening to music very hard and wanting to play very much, but I had to get off the scene to get that enthusiasm back. Because I’d lost it.

Derek and the Dominos were recording in here when we broke up and I went into that dark place. I didn’t give a shit about the music anymore. We’d come in and just argue all day and have a go at one another, and then one of us would blow up and split. The music didn’t matter. I didn’t like the sound of my guitar, I didn’t like the way I played, and it took me a while to go away and come back to it. When I came back, it was with a different point of view, a fresh enthusiasm and a kind of open-mindedness to learn about new music, because that’s when I heard reggae. I was just like a kid in a sweet shop again.

GW You toured a hell of a lot throughout the Seventies.

CLAPTON Toured and recorded and got out of it! I had a great time, but it was all fairly directionless. I mean, I don’t regret any of it, to be honest; I think there was no other way for me to go, in a way. I’m just very grateful that I survived it and didn’t die, because I was often in some very seriously dangerous situations with booze and drugs. I used to do crazy things that people would bail me out of, where I was risking life and limb in cars or in different life-threatening situations. And I’m just grateful that I survived. But the music got very lost; I didn’t know where I was going and I didn’t really care. I was more into just having a good time, and I think it showed. I think I got fairly irresponsible, and there were some people that liked it and other people that got very pissed off.

And my guitar playing took a back seat. I’d gotten fed up with that thing about “The Legend”—I wanted to be something else and I wasn’t really sure what that was. I was just latching onto people and trying to be like them, to see if something else would emerge. And all that did emerge, in the long run, is what I am now. I don’t really know what that is as a definition except it’s more in tune with what I was at the beginning— which is a blues musician.

GW It has been said of those days that nobody could actually predict what any given Eric Clapton concert was going to be like.

CLAPTON It would depend very much on who I’d bumped into that day—who had managed to corner my attention— because then I’d just go off with them. I was just like a grass in the wind: I went anywhere. I was literally anybody’s, depending on what they were holding— you know, what drug or what drink they were on. Then there’d be the gig in the evening, and I’d be wherever that was, wherever I’d been taken.

GW That period ended dramatically around 1984-1985. Suddenly, there were projects like Edge of Darkness and the Roger Waters album The Pros and Cons of Hitch Hiking, which saw you playing with much more fire and power. But it was probably Live Aid that was responsible for reestablishing you in many people’s minds. Did the reaction you received surprise you?

CLAPTON Yeah! I’m not sure I was even able to take it all in. I’ve always been a very, very self-effacing or low-self-worth sort of person. When they told me where I was going to be on the bill, I didn’t get it. I thought, What? Really? And that really did a lot for me. And that reception—it was mind blowing! From that point on, I stared to give myself a bit more of a pat on the back and to be kind to myself.

GW Did the multiple Grammys for Unplugged take you by surprise?

CLAPTON Yeah, I must admit I found it all a bit overblown. I mean, I thought the album was quite rough, to say the least. I think most of the recognition and applause was wrapped up in another gesture—which is beautiful and I don’t want to put that down at all. I appreciate all of it, but I felt it was all a little bit blown out of proportion. And frightening. If I’d taken it too seriously, it could have done me in.

GW There have been lots of books written about you. What do you think of them?

CLAPTON I think they all take it far too seriously. It’s a bit like the “Clapton is God” thing; they all follow on from that. Survivor [Ray Coleman’s 1993 authorized biography] has got a hint of that. It’s all a bit reverent, isn’t it? I don’t really see myself as being that heroic. I was just lucky to be in the right place at the right time and very fortunate to have survived. So I am a survivor, but it all ought to be taken a little less seriously, I feel.

I think if it’s due to anything, it’s just the fact that I’m fairly honest about what I do. I just try to do the best and carry on working, and do it as simply and unaffectedly as possible. I’m not bullshitting people: all I really want to do is to play with dignity and self-respect. I’m making a blues album because things have come full circle. It’s been 30 years and I’m doing what I’ve always wanted to do. I’m fulfilling myself for other people too, because I’ve always been badgered about this. People are always saying, “When are you going to do this blues album that you’re always on about?” And I’m doing it! It then frees me up, opens the door for whatever’s next, and it will be interesting to see what that is going to be,

GW At the Albert Hall this year, not only were you using a Les Paul again, you were playing a great many vintage Gibsons. Are you using them on the blues album?

CLAPTON Yeah. This album is paying respect to the records the way I heard and felt about them, as much as possible. And so, when I’m singing and playing, I’m trying to be me being Freddie King. Of course, that doesn’t happen, because it still comes out as me, but I’m doing it as much as I can: in the way we record it, for instance, all on the floor at the same time; with the instruments I play and the way I sing it—everything to try and be as true to my recollection of the experience as possible. Not that I want to copy the original record that closely, but the experience— the emotional way it felt to me.

GW Singing “Tears in Heaven” and “The Circus Left Town” must be extremely difficult for you.

CLAPTON It’s been close on occasions where I could choke and not be able to do it, but then what would happen? We’d have to stop and it would get mawkish and embarrassing. At the same time, to back off and pretend that it’s about nothing and just play it as if it was a song that had no meaning would be pointless, so there’s a thin line you have to tread, somewhere in the middle. It does require a fair amount of discipline, concentration and focus to stay in the right place and not step off the tightrope either way.

GW Are you going to record “The Circus Left Town”?

CLAPTON Yeah. I wanted to talk to the record company about recording another album alongside this one and putting it out as a double album, but at the moment it seems that they’re not in agreement. It’s not just “The Circus Left Town”; there’s another one that I wrote about my son called “My Father’s Eyes,” which was part of the Unplugged program but didn’t get in there. There are a handful of songs that are in that mold, and some other stuff, too, which is more rock and roll, so that will be on perhaps the next studio rock album, if that’s what’s going to happen. But at the moment, all I can see is this blues thing and being true to that.

GW How did you go about choosing the track for this record?

CLAPTON Well, they’re just the songs that I’ve always loved out of my record collection: blues masterpieces that have had some kind of profound effect on me, like the Jimmy Rogers song “Blues All Day Long.” There’s something about that: the balance of the instruments and the way it’s recorded. The beauty and the strength of it have always taken my breath away and always will. I don’t do it quite the same way, but what I’m trying to recreate is the emotional experience that I got when I heard it. There was something about all of those songs that took me to some beautiful place and made me feel better or gave me cold chills when I heard them, so I’d try to make that happen again by playing them.

GW Do you think there are any modern blues songs written today which do the same kind of thing?

CLAPTON Yeah, oh yeah. In fact, I would like to do a couple of Robert Cray’s songs. He’s the last of the great heroes, I think. A great singer, writer and player, too.

GW Have you got any advice for today’s guitar players?

CLAPTON Listen to the past. I’ve run into a lot of players in the past 10 or 15 years who didn’t really know where it was coming from. They thought it came from Jimmy Page or Jeff Beck, or they thought it came from Buddy Guy or B.B. King. Well, it comes from further back, and if you go back and listen to Robert Johnson and Blind Blake and Blind Boy Fuller and Blind Willie Johnson and Blind Willie McTell, there’s thousands of them that all have something that led to where it is now. The beauty of it is that you can take one of those things and make it yours. But by learning too much from the later players, you don’t have that much opportunity to make something original. I listened to [New Orleans trumpet player] King Oliver, Louis Armstrong, Jelly Roll Morton, Thelonious Monk, Charles Mingus, John Coltrane and Archie Shepp. I listened to everything I could that came from that place that they call “the blues” but in form isn’t necessarily the blues.

GW A lot of those guys are jazz players.

CLAPTON They are, but they all would acknowledge that if you can’t play the blues, you can’t play jazz anyway. So, listen, listen, listen, and go back as far as you dare. That’s what I still do today. I still listen to Leroy Carr and Scrapper Blackwell for their beauty and simplicity and to get a feeling, because that’s what it’s about. It’s not about technique, it’s not about what kind of instrument you play or how many strings it’s got or how fast you can play or how loud or quiet it is; it’s about how it feels and how it makes you feel when you play.

GW Finally, you once said you had two ambitions in life: one was to play one note in a blues solo that could bring an audience to the verge of tears, and the other was to sleep with 10,000 women. Have you…

CLAPTON No—and I haven’t slept with 10,000 women either. Still got both of them to do…if I live that long.