Glenn Hughes: “People talk about my vocals, but I’ve never, ever felt this good about playing bass“

The ‘Voice Of Rock’ and Deep Purple icon speaks candidly about his bass playing over the decades, why he should have never left Trapeze, and how the Dead Daisies reignited his four-string fire

The British-born, California-resident singer, songwriter and bassist Glenn Hughes must have a streak of immortality somewhere within him. Now 69 years old, he appears on Holy Ground, the new album from the Dead Daisies – an American, Australian and British supergroup – and sounds all of 25 years old.

Hughes has been nicknamed the ‘Voice Of Rock’ for decades with good reason, although that phrase undermines the soulful, funky nature of his vocals, and also takes the focus off his amazingly adept bass guitar playing, the reason why we’re interviewing him today.

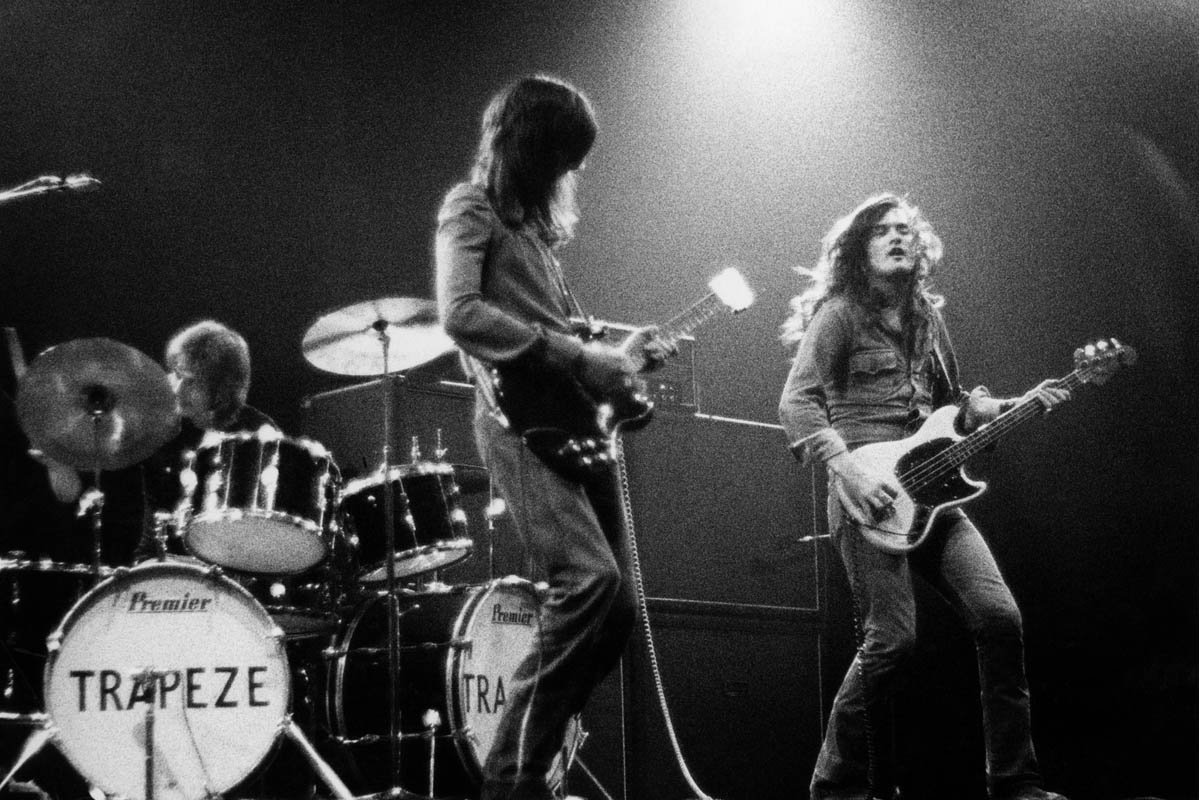

For those not in the know, Hughes was born in Cannock in the British Midlands in 1951, honed his chops in the underrated funk-rock band Trapeze as a teenager and then sprang into the limelight in 1973 when he was recruited into Deep Purple, then one of the biggest bands ever formed.

Recording and touring with Purple for the next three years, Hughes was enveloped by a blizzard of drugs and alcohol from which he only fully emerged in 1997, by which time he was a solo artist, having worked with a range of musicians and bands such as Gary Moore, Pat Thrall and Black Sabbath.

You can read about all this crazy stuff in Hughes’s 2011 autobiography – full disclosure; I was his co-writer – but today we’re here to look back at his last decade or so, when he’s recorded as a solo musician, alongside guitarist Joe Bonamassa in Black Country Communion, and now with the Dead Daisies.

Of the current band, he muses: “When the Dead Daisies asked me to come in – and this is 18 months ago, before COVID – I’d done the Glenn Hughes Sings Deep Purple tour for two-and-a half years, and I wanted to do something more. When this came up, I thought ‘Let’s give it a go.’ They brought me in for the songwriting, bass, and vocals, so I got to do what I normally do – and it worked out well.”

I went to NAMM and Cliff Cooper asked me if I wanted to check out an amp. So I went into their booth and there was a P-Bass on the wall and I plugged it – with no effects – and I’m going, ‘Oh my God, there’s that sound!’

One song on the new album is called Like No Other (Bassline) and starts with a monstrous slab of overdriven bass – and is the obvious place to start, in our case.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“On that song, we went in to cut it live,” recalls Hughes. “I was singing and playing bass, and there was a mic set up. We do that with Black Country Communion as well, because sometimes we use the live vocal. I kept singing ‘Can you feel my bassline? You’re like no other’ and I’m thinking ‘This could be a hook here, you know.’ The rest of the band loved it, and now it’s my favorite song on the album.”

Where did that huge bass tone come from? “Orange!” he says. “Back in the '70s, I knew about Orange amps, of course, but it was only about 10 years ago that I went to NAMM and Cliff Cooper [Orange founder] asked me if I wanted to check out an amp. So I went into their booth and there was a P-Bass on the wall and I plugged it – with no effects – and I’m going, ‘Oh my God, there’s that sound!’

“It was the Trapeze sound, and I basically switched to Orange overnight. They’ve been incredible to me. The bass sound you’re hearing now, on BCC’s last album, on my last solo album Resonate (2018) and on the new Dead Daisies album, is the real signature sound of mine.”

As for bass guitars, he explains “I’ve got a lot of classic Sixties basses, and I always fear losing one on the road – like I did with my Deep Purple P-Bass in 1977 – so they stay at home because I don’t want that to happen again.

“I was in a music store in Australia about 10 years ago, and I was playing basses that I thought were vintage models – and they were new Bill Nash instruments. So when I joined BCC I called Bill up. I have four or five of his P-Basses and the same number of Jazz basses.

“Every one is brilliant: Bill doesn’t make bad basses. I’m playing a Nash J-Bass at the moment and it’s incredible. I use them with D’Addario strings, and I want to mention my Jerry Harvey Ultimate Ears too, which really work for me. I’ve got a Black Cat Octave Fuzz pedal which gives me an amazing sound – oh my God, it’s unbelievable.”

I’m very free, and you can actually hear that. I’m really in the moment when it comes to bass – it really means the world to me

After all these years, has bass changed its role for Hughes? “You know,” he ponders, “I’m at a point now where I’m saying to myself, ‘Glenn, you’re doing pretty well on the bass, aren’t you?’ People talk about my vocals, but I’m really enjoying bass nowadays, more than ever before. I’ve never, ever felt this good about playing bass.

“I write more than I used to write; I’ll sit upstairs in my studio, playing all the instruments, and when I get to play bass on the songs that I’ve written, I realize that I’m really enjoying it. I’m very free, and you can actually hear that. I’m really in the moment when it comes to bass – it really means the world to me.”

Does he ever listen back to his early recordings and assess his youthful bass playing, I wonder? He pauses before replying. “When [early group] Finders Keepers split and we formed Trapeze, that’s when bass started to get funky for me. I’ve heard some Trapeze bonus tracks recently that I hadn’t heard before, and the bass was really something – and I was only 17 or 18. I was shaking my head as I heard it, thinking ‘Was I playing like that at that age?’ You can clearly hear that I was really into it.”

And Deep Purple? “Well, the Gettin’ Tighter midsection is good when I slap on the bass – I never did very much of that. I’m not a slapper, generally. With no disrespect at all meant towards Deep Purple, there’s not much swagger going on in that band. It wasn’t a great role for me as far as the bass player that I am goes. Songs like Burn are very straight and strict, you know.”

He adds: “I realize how lucky I was to have found myself as a bass player in 1967, when the bass player from Finders Keepers left the band. I had 24 hours’ notice to switch from playing guitar to playing bass on cover songs like Fire Brigade by the Move.

“People ask why I play with a pick – well, it’s because I had to switch from guitar so quickly. Andy Fraser told me that I sound like a fingerstyle player. Nobody realizes how much of an influence he was on me – he was the guy.”

Here’s a story that few people have heard. The late Fraser, famous for the band Free and his 1970 bass-heavy hit All Right Now, is doubly relevant here because he and Hughes shared the cover of Bass Guitar magazine back in January 2013. We sent the two bassists off to interview each other over lunch in Hollywood – now that’s a date we wish we hadn’t missed.

On Fraser’s death two years later, his family told us that they placed that issue of the magazine (above) at his seat at their dinner table, to give some sense of him still being there with them. It’s a poignant tale, and one that causes Hughes a pause for thought.

“You know, I’ve lost a lot of people in my life, but the man I’ve become because of it is really about letting go of expectations and resentment. I had so much attachment to things and people and places – and when you have to let go of them, it’s difficult.” Hughes then makes an unexpected admission.

“I’ll say this to you now: I really should never have left Trapeze. I should have stayed on that boat. That’s the way I feel these days – truly. Leaving Trapeze has been the torment of my life, but I had to let it go.”

I’m most proud of getting clean and sober. I’m 23 years sober now, I’m happy to tell you. If I hadn’t done that on November 23, 1997, I’d be dead

Would the cocaine and booze addictions have been avoided if he’d stayed away from Purple, I ask? This turns out to be difficult to answer. “I really hope so,” he replies. “I guess it might have caught up with me later, but I only ever drank the odd half-pint of cider when I was 18 or 19 – I never craved the devil’s dandruff. When cocaine popped up in America in 1971, I just didn’t want it. If I’d stayed in Cannock all my life, I would probably never have found it – so I don’t know the answer.”

Let’s end with a big question. What makes Hughes most proud? The answer is instant: “I’m most proud of getting clean and sober. I’m 23 years sober now, I’m happy to tell you. If I hadn’t done that on November 23, 1997, I’d be dead. That’s when the light went on.”

“But you know,” he smiles, “what a life I’ve had. All these years later, at the age of 69, I can do this – because I work the spiritual lifestyle. It’s really saved my life.”

“I was in Trapeze for four years, during which time the band switched from a quintet to a trio – which was me, Mel Galley, and drummer Dave Holland, later of Judas Priest – and we released three albums. We could have gone a long way; I think the band never got the success they deserved in the UK.

“America loved us. Get this snapshot from my early career. Trapeze played three nights at the famous Whisky A Go-Go in Los Angeles in December 1970, and we did great. We did 15 more shows in 15 days and ended up back in LA. We didn’t have enough money to get home, though, so we phoned our agency and they said, ‘Well, you can’t play in New York again, because you’ve just played there.’ So we said ‘How about somewhere in between?’ because we didn’t have any money.

“They came back to us the next day and said ‘There’s a club in Houston that really wants you to play,’ so we went to Houston and they sold out the first night, with 600 or 700 people. Then they asked for a second night. That one gig broke Trapeze in America.

“This was long before any drugs: We were drinking Cold Duck, which is a cheap, wine-type beverage. We’d opened for the Moody Blues and we’d been working hard: The strength of our show in Houston, Austin, and Dallas supporting the Moodies had made us big in Texas, which has always loved rock trios. That was the turning-point for me, when I knew that we’d achieved something big.

“The whole of 1971 for me was about touring the USA and having encounters with girls. It was an age of innocence: I remember going to our manager Tony Perry and asking him for five dollars. We’d have parties in our hotel, and people would be smoking opium and PCP and snorting coke, and I’d look at them and think ‘These people are insane’.

“We’d go to the houses of the record company executives and they’d be smoking dope and swimming naked in the pool. “It was like the film Almost Famous, but I’d be a shrinking violet in the corner, standing there with Tony Perry and Mel and Dave, saying ‘Look at those fucking drugs!’ I had a very normal life and I was very frightened of drugs. Even when I took a Tylenol or an Advil, I’d be like, ‘I don’t want to do this!’”

- Dead Daisies' new album, Holy Ground, is out now via Spv.

Joel McIver was the Editor of Bass Player magazine from 2018 to 2022, having spent six years before that editing Bass Guitar magazine. A journalist with 25 years' experience in the music field, he's also the author of 35 books, a couple of bestsellers among them. He regularly appears on podcasts, radio and TV.