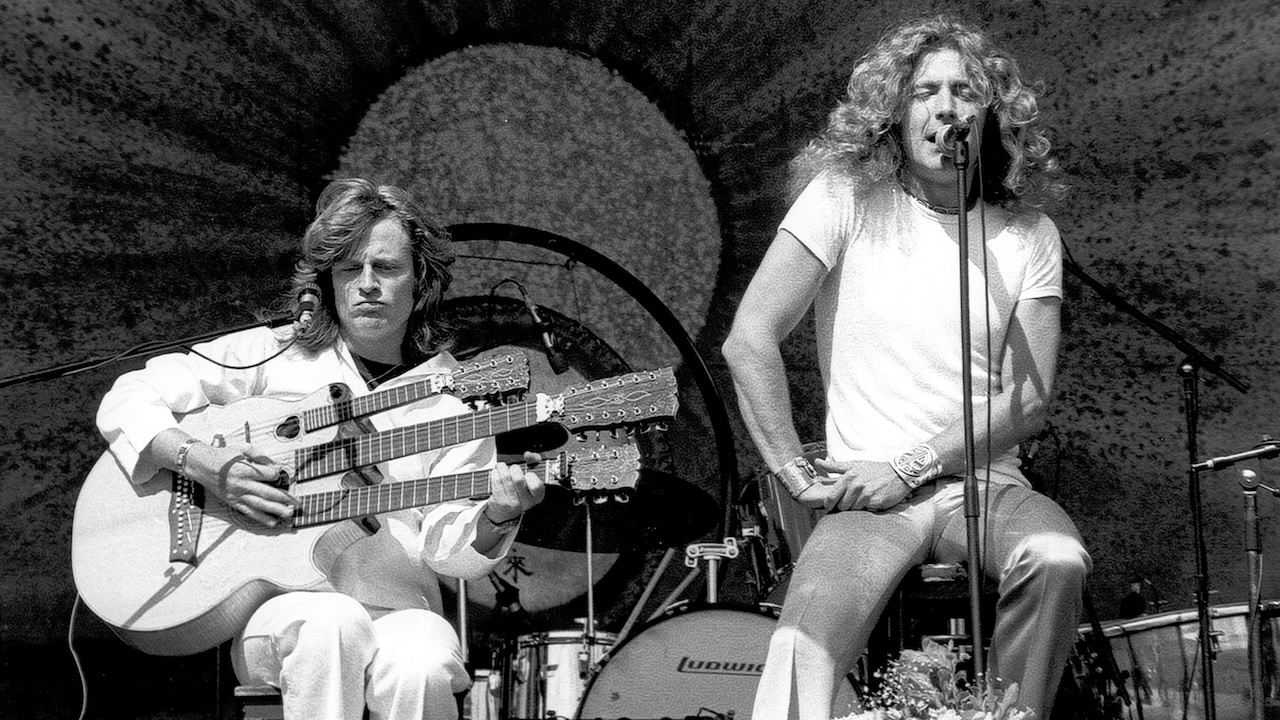

“I’d be there with bass pedals, a triple-neck guitar and keyboards, and Robert Plant would ask, ‘Can you sing, as well?’” How John Paul Jones became Led Zeppelin’s ultimate wingman

Armed with years of experience as a session bassist and arranger – having worked with the Yardbirds, Jeff Beck and the Rolling Stones – John Paul Jones could do it all

It's hard to think of another band that has had as monumental an impact on the heavier end of the rock spectrum as Led Zeppelin. One major component of their success was the solid, funky and bluesy rhythm section of John Paul Jones and the late drummer John Bonham.

Though his onstage persona was perhaps less flamboyant than his bandmates, Jones was never a bass player to sit in the shadows. From his tight riffing on tracks such as Black Dog to the funky grooves of Trampled Under Foot, Jones doled out high-quality basslines on every cut.

Although Jones gets more attention for his bass playing these days, he was also Zeppelin’s go-to keyboardist, often switching between bass guitar and keys during live shows. In fact, it was a standing joke in Led Zeppelin that if there was an exotic instrument needed for a track, John Paul Jones would take care of it. Organ, mandolin, recorders? No problem.

As he told Bass Player in 2008, “I’d be there with a triple-neck guitar, bass pedals, and keyboards, and Robert would ask, ‘Can you sing, as well?’”

The following interview from the Bass Player archives took place in May 2008.

What was your contribution to Led Zeppelin's overall sound?

“I was a sort of Motown and Stax specialist when I was a studio musician, and I brought that groove into Led Zeppelin. Bonzo was also a big R&B fan, so there's a lot of it in the Zeppelin rhythm section. In addition to keyboard, mandolin, and other things like that, I just brought my musical experience.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“I've always said that Zeppelin was the space between four individual musicians, and it was bigger than the sum of its parts. We all had different musical tastes, and we didn't try to emulate any other band. Soul, jazz, country, folk, Arabic, Indian – we all had these different influences, and we weren't ashamed to whip them out at any time. The way those influences mixed became Zeppelin.”

What was the first Zeppelin rehearsal like?

“We met up in a tiny room in London and all looked at each other, working out what we were going to play. It was kind of like, ‘Well, what do you know?’ ‘I don't know, what do you know?’

“Page said, ‘Do you know The Train Kept Rolling?’ I said no, and he said, ‘Its in E, but there's a riff that starts on G.’ He showed me the riff and counted it in, and the room just exploded. We all knew we had something special.”

Bonham's drum phrasing was unusual.

“Absolutely. He was like that – a very imaginative drummer. He could pick out the interesting parts of a riff and come up with a really cool part.”

How would you go about matching up with his drums?

“Since Bonzo's kick-drum playing was so complex, it was much more effective to synchronize and play with the kick rather than just boom right across it. That was part of our style; I would leave out notes in order to let a kick or a snare come through. That's especially effective with a really good drummer – it makes the rhythm come alive when you leave holes for the drums to pop out.”

When and why would you switch from playing fingerstyle to playing pickstyle?

“My preference is fingerstyle, but l often had to play with a pick in the session days, so I got quite used to it. I can play Immigrant Song with my fingers, but it just sounds better with a pick. Same with Black Dog. It just gives you different phrasing, and a more metallic, guitar-y sound. I didn't see any reason not to swap one for another if the occasion demanded it.”

How did Zeppelin communicate onstage?

“There was eye and ear contact. Robert always used to tell me to stand up in the front. I used to play the first song up front, then I'd gradually edge my way back to my favorite position: just under the ride cymbal off the corner of the drums, where I could feel the kick.

“For improvised parts we would group around center stage with a lot of eye contact, and a lot of focus. That concentration is what made it successful. Anybody could take anything anywhere, and we'd all follow.”

What was your keyboard setup?

“It changed over time. I used to use a Mellotron, which was the only way you could get a string or flute sound in those days. But you'd never know whether it was going to be in tune, so I replaced that with a Yamaha GX1, the big green machine. In the end, I think I used a Fairlight, an early 8-bit sampler.”

What was the band's approach to recording and touring?

“To me, Led Zeppelin was a live performance band. We would make a record and that would be the blueprint. Then we'd go off and play the record live, and it would move on from there. I'm pretty used to recording studios, so it was no big thing to be in the studio. Playing live was the most fun for me; I think that was the best of Zeppelin.”

Nick Wells was the Editor of Bass Guitar magazine from 2009 to 2011, before making strides into the world of Artist Relations with Sheldon Dingwall and Dingwall Guitars. He's also the producer of bass-centric documentaries, Walking the Changes and Beneath the Bassline, as well as Production Manager and Artist Liaison for ScottsBassLessons. In his free time, you'll find him jumping around his bedroom to Kool & The Gang while hammering the life out of his P-Bass.