“When companies have success, or they have iconic models, we can tend to get lazy... Consumers and artists deserve better – they need to feel like we’re working hard”: How Martin made its groundbreaking Inception acoustic

Martin's vice president of product management Fred Greene gives us the skinny on how the brand's latest acoustic presents players with some seriously innovative features

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Maple acoustic guitars have long occupied a respectable, if marginal, place in the world of guitar design. As a tonewood, maple is beautiful and abundant and, in fact, it has greater potential as a sustainable material than traditional tonewoods from the tropics.

And yet, over the years, guitar designers have struggled to open up maple’s voice and grant it attractive richness to complement its natural clarity. Now, however, Martin’s design team think they have found a way to unlock the full potential of maple using deft and innovative design that allows it to reproduce a broad palette of sounds.

The resulting guitar has been named the Inception. We join Fred Greene, the company’s vice president of product management, to find out how the Inception is spearheading Martin’s push to intelligently innovate rather than simply service its revered historic models.

How did the new Inception project first take shape?

“For a long time, we’ve had this discussion around our concerns about exotic hardwoods – the viability going forward, how much longer are we going to be able to get the mahoganies and the Guatemalan rosewoods, and so on, in any numbers going forward?

“Then, at some point, we understood that we’re going to need to build more instruments – or at least create a path for building instruments – out of more sustainable hardwoods, stuff that maybe is sourced in the United States or Europe or places like that.”

“We actually tried it before. We’ve made maple guitars before, and some are pretty good. We’ve made walnut guitars, and lots of different domestic hardwood guitars. But in the end, the consumers vote with their dollars and they just did not really embrace the products the way we’d hoped they would. They still just wanted a rosewood guitar; they just wanted a mahogany guitar. And that’s what we’re good at.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“So as we were having the conversation about maybe building another maple guitar, or trying to build another sustainable model, I said to the R&D team: ‘I think we just need to take a completely different approach. I feel like we’re trying to force this wood into a design or a body shape or a recipe that it wasn’t originally designed to be a part of.’

“We started to have the conversation that, you know, Martin being an older company, most of our designs evolved around rosewood and mahogany. We were trying to create specific sounds or just trying to make the guitars be a certain way based upon the wood.”

“But when you change a key component of that recipe – in this case the back and the sides – it would seem logical that you might want to change something else within that recipe. I keep using this analogy: everybody loves apple pie, but what if all of a sudden you decide to change the key ingredient, apple?

“You might say, ‘I want to use a different kind of fruit – how about a tomato?’ Well, that would require you to change more things in the recipe than just that one key component – you wouldn’t continue with the same recipe, just simply substituting tomatoes for apples.

“So that was our thinking: let’s go see if we can make maple sound a little more the way we want it to sound, as opposed to how it sounds in a recipe that it wasn’t designed to be part of. I said, ‘Let’s try to rethink some things. Let’s find out some construction techniques… maybe some concepts that other people have experimented with and see if we can put those to work for us.’

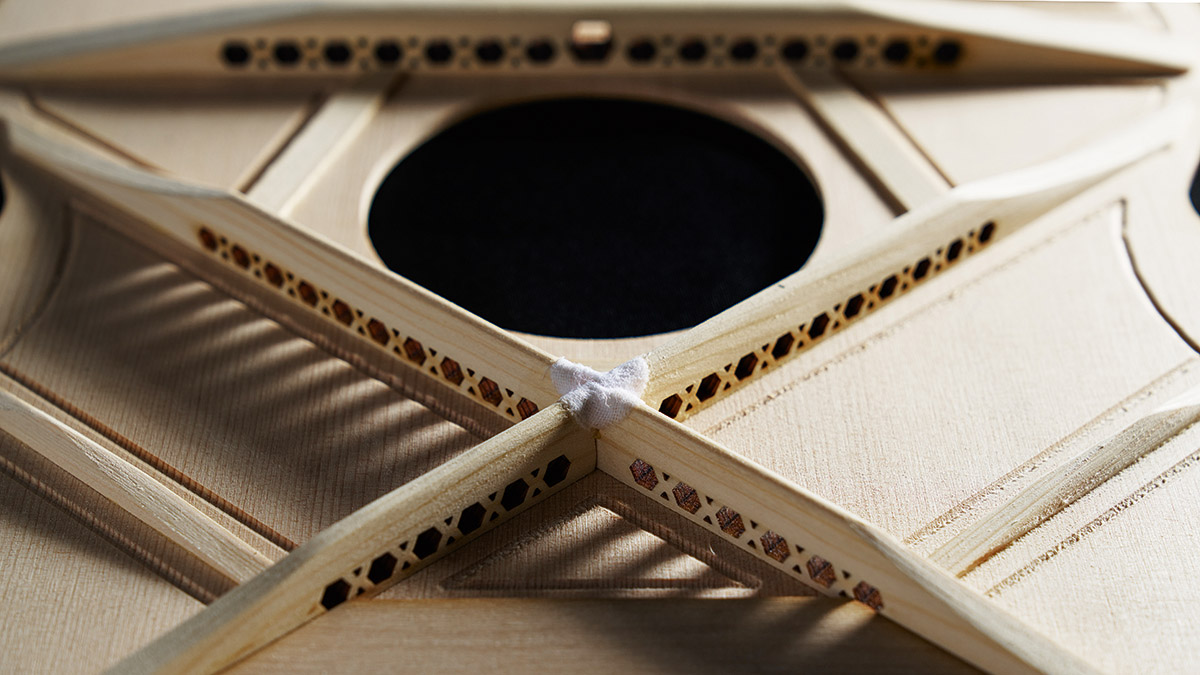

“For example, we aren’t the first people to put holes in braces. [Southern Californian luthier] Kevin Ryan’s done it and I know other small builders, who’ve done it… But we wanted to put our unique take on it and see if we can lighten up that top, make it be a little bit more responsive, make the maple have a little bit more overtones to it that we didn’t feel like we’re getting out of our current recipe. That was the thinking.”

The Inception’s bracing incorporates an interesting lattice of hollow, hexagonal-section reinforcements. Are these designed to retain strength while removing mass from the bracing?

“Yes – a honeycomb shape is a really strong shape and it was something we could do. We also wanted to make it look visually striking. I mean, part of this is the psychology of making guitars. If you’re going to do something different – and it’s kind of happening underneath the hood, so to speak, underneath the bonnet of the car – you’ve got to give the consumer some visual cues that this is going to be different from what they should be expecting.

One reason we didn’t make this using a dreadnought because if I made this guitar as a dreadnought all people would say is, ‘That’s interesting. What would it sound like with rosewood?’

“That’s one reason we didn’t make this using a dreadnought [as the body shape] because if I made this guitar as a dreadnought all people would say is, ‘That’s interesting. What would it sound like with rosewood?’ And then I’m right back in the same boat all over again.

“So I wanted to use a non-traditional body shape for this series, our Grand Performance shape. I wanted to use the non-traditional bracing pattern and some other stuff to let people know it’s not trying to be a dreadnought, it’s not trying to be a 000. It’s very much its own thing with its own voice.”

It’s interesting as it seems that the guitar designer’s job touches on human psychology almost as much as it does pure lutherie and engineering.

“Correct, 100 per cent. We’re not running a university where we’re just doing experiments and then publishing papers afterwards, explaining to the world what we tried and whether it worked or it didn’t work.

Lots of times guitar players think every guitar you come out with is aimed at them. That’s not the case at all. Some guitars are aimed at different consumers

“I mean, in the end, it is a commercial business and we’re trying to sell guitars. But the guitars do need to perform and they need to deliver something unique to the consumer so that they’re willing to part with their hard-earned money in order to experience it.

“We understand that when people buy guitars, they don’t buy just with their ears. We know that they buy with their eyes also, so they want to see something. And we know there’s certain consumers out there who are traditionalists, and there are other consumers who are early adopters.

“I think lots of times guitar players think every guitar you come out with is aimed at them. That’s not the case at all. Some guitars are aimed at different consumers – and it’s possible this may not be the guitar for you if you’re playing folk music or bluegrass music or something like that…. If you’re buying a Porsche 911 it’s not really aimed at the guy who’s working construction at a job site; that person may want a truck. It’s just a little bit different.”

There are interesting narrow channels carved in the underside of the top of the Inception model. What are those intended to do?

“Yeah, the tone channels that we’ve cut into the instrument just allow the top to move a little bit more around the braces, to sort of vibrate – the top acts almost like an air pump. So the strings are the actuator and then the top vibrates up and down. All we wanted to do was to free the top up a little bit more.

“We had considered making the top thinner in general. Because most of our tops right now are finished at 120 thousandths of an inch thickness, and you can take them down to about 105 and probably be okay, for the most part. The problem is when you start getting really thin like that, you start to lose some of the structural integrity of the instrument. Also, the instrument can start to lose headroom, you know; the top gets a little too flabby.

We wanted to find a way to let the top move a little bit more but not lose too much of that structural integrity and mass. I wanted it to be able to still have the headroom if you banged on the guitar pretty hard

“So we wanted to find a way to let the top move a little bit more but not lose too much of that structural integrity and mass. I wanted it to be able to still have the headroom if you banged on the guitar pretty hard. So these channels cut around the braces allowed it to move.

“We have lighter braces in there, but we tested all the braces and they’re just as strong with the holes in them as they are without the holes. We thought it was a nice elegant, interesting way to attack the problem of allowing the top to move a little bit.

“I think it’s cool, I think it’s fun – and it does change the sound. We’ve done some nodal testing on the computer where you can see that the top does vibrate differently with the braces and the sonic channels compared with a stock model without those elements. It is a different sound, for sure.”

What is it about maple that you felt necessitated a fresh approach with this project, design-wise?

“I know some people really like the sound of maple and I think it works on some guitars. I think it works in some recipes, but it didn’t necessarily work the way we wanted it to work in all of our Martin recipes. Gibson has been making maple guitars obviously forever with its J-200s.

“But our issue with maple is it can sound a bit stiff: you get a strong, quick fundamental note off of maple and then it sort of sounds a little compressed and decays quickly, and you just don’t get a lot of nuanced overtones over the top of that. Some people like that sound and that fits the way they play or what they’re trying to achieve. It actually records pretty well because of that.

Our issue with maple is it can sound a bit stiff: you get a strong, quick fundamental note off of maple and then it sort of sounds a little compressed and decays quickly,

“But we wanted to try to create something that, as a sound, was a little more sophisticated. As a tonewood, there was a lot going on with maple that we really liked, but we felt like it just needed a little bit more help. We were probably hurting it with the way we were building tops and some other elements on the instrument.

“So we added in that little bit of walnut in the back, with the wedge, to help soften up some of that tone and give it a little bit more sweetness in there because walnut is sort of in between a rosewood and a mahogany in the way it sounds.

“Then, of course, letting the top move a little bit more, so the notes didn’t decay quite as quickly. We felt like that was a good compromise to make it a little bit more sophisticated in sound. Then you add in a walnut bridge and a walnut fingerboard and a walnut neck… it all starts to work together to sweeten up that tone.”

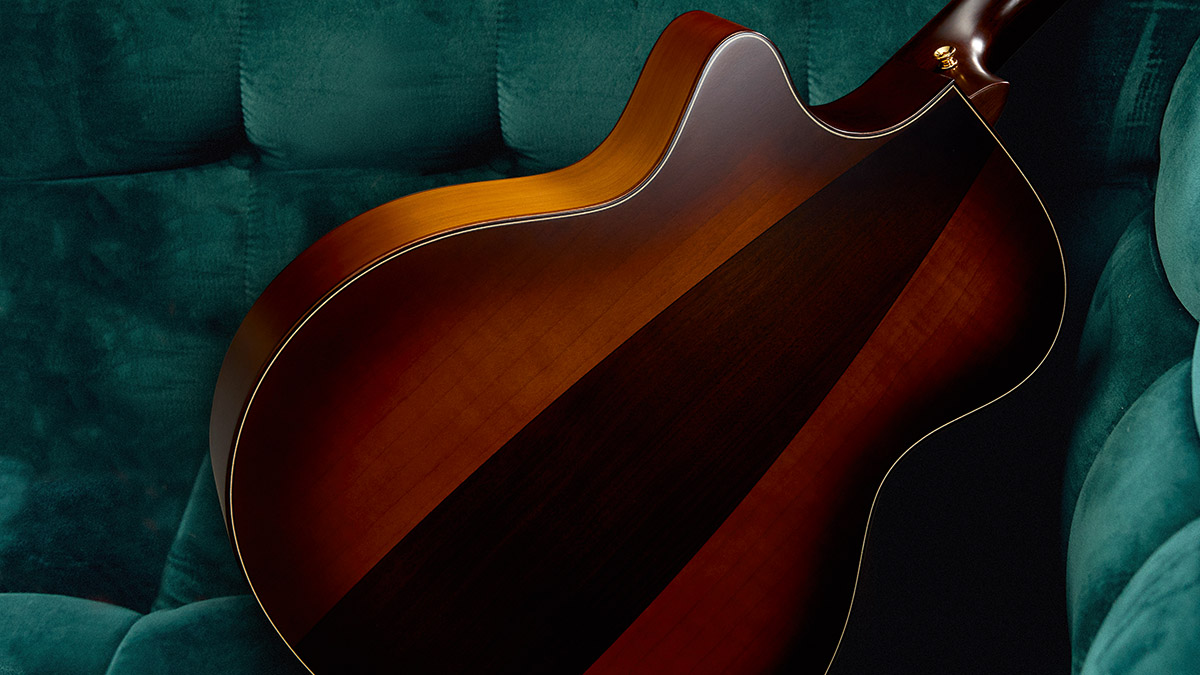

We love the curved shape of the inset walnut panel on the back of the guitar. Was that purely an aesthetic choice?

“Actually, there was a purpose to it. We thought about just going with a standard D-35 style wedge in the back. But we wanted to get the most out of that piece of walnut; we didn’t want to waste any of the wood.

“Obviously, it’s a sustainable model, so what you’ll see is that the actual widest point of the wedge in the back is directly underneath the bridge. We were trying to capture some of the sonic tone that comes off the bridge; we know that a lot of the tone that comes from the guitar is right there behind the bridge on the top.

“We tried to reflect some of that walnut – we wanted to maximise the tone we were getting out of that – so we thought it was once again a good, interesting and visual cue to the consumer that this was something a little bit different and non-traditional. But there was an actual engineering reason why we did it.”

Did the success of the SC series of acoustics, with their innovative neck joint and offset body, allow you to dream a bit bigger when it came to further innovation?

“Absolutely. I mean, we’re not going to walk away from dreadnoughts and 000s and 00s and the traditional things we do. That’s who we are. Ultimately, we know we do those things really well and we’re going to continue to do those things, going forward. However, we’re not going to allow people to box us in and say, ‘This is all you can do.’

“Martin has always been an innovative company. We’ve been lucky, fortunate, blessed to have created some really iconic models and shapes and bracing patterns and all of those things – and we’ve certainly enjoyed the success of that. But we want to continue to provide artists and players the opportunity to try new things. We think we’re uniquely positioned to provide that to people. We’re not going to leave that up to everyone else and hope they come up with a good idea. We feel like we have good ideas and things we want to try.

“The SC was sort of a shot over the bow to everyone to say, ‘Hey, we could do really innovative, interesting concepts and guitars going forward.’ And we’re going to continue to build on those. I think what you’re seeing from Inception right now, it’s just the first shot of what we’re going to do with some of these domestic hardwoods.

“We are already working on the second version, which is very different from the first version: it will utilise some of the same concepts but in a different way. Once again, if you’re going to change key ingredients in your dish, you need to start changing the recipe in general.

“So if we’re going to use a different wood, we’re going to make some other changes, we’re not going to say it’s a one-size-fits-all. In other words, we’re not going to make X-brace dreadnoughts and then just stick in every kind of wood in the world and go, ‘Hey, what do you think of this?’ I think that’s a little lazy from a design standpoint.

“I think when companies have success, or they have iconic models, we can tend to get lazy, just try to milk people with the same old thing. But I think the consumers and the artists deserve better than that. I think they need to feel like we’re working hard to provide them with new sonic possibilities. And we shouldn’t leave that up to just the digital world to do that for them.”

Jamie Dickson is Editor-in-Chief of Guitarist magazine, Britain's best-selling and longest-running monthly for guitar players. He started his career at the Daily Telegraph in London, where his first assignment was interviewing blue-eyed soul legend Robert Palmer, going on to become a full-time author on music, writing for benchmark references such as 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die and Dorling Kindersley's How To Play Guitar Step By Step. He joined Guitarist in 2011 and since then it has been his privilege to interview everyone from B.B. King to St. Vincent for Guitarist's readers, while sharing insights into scores of historic guitars, from Rory Gallagher's '61 Strat to the first Martin D-28 ever made.