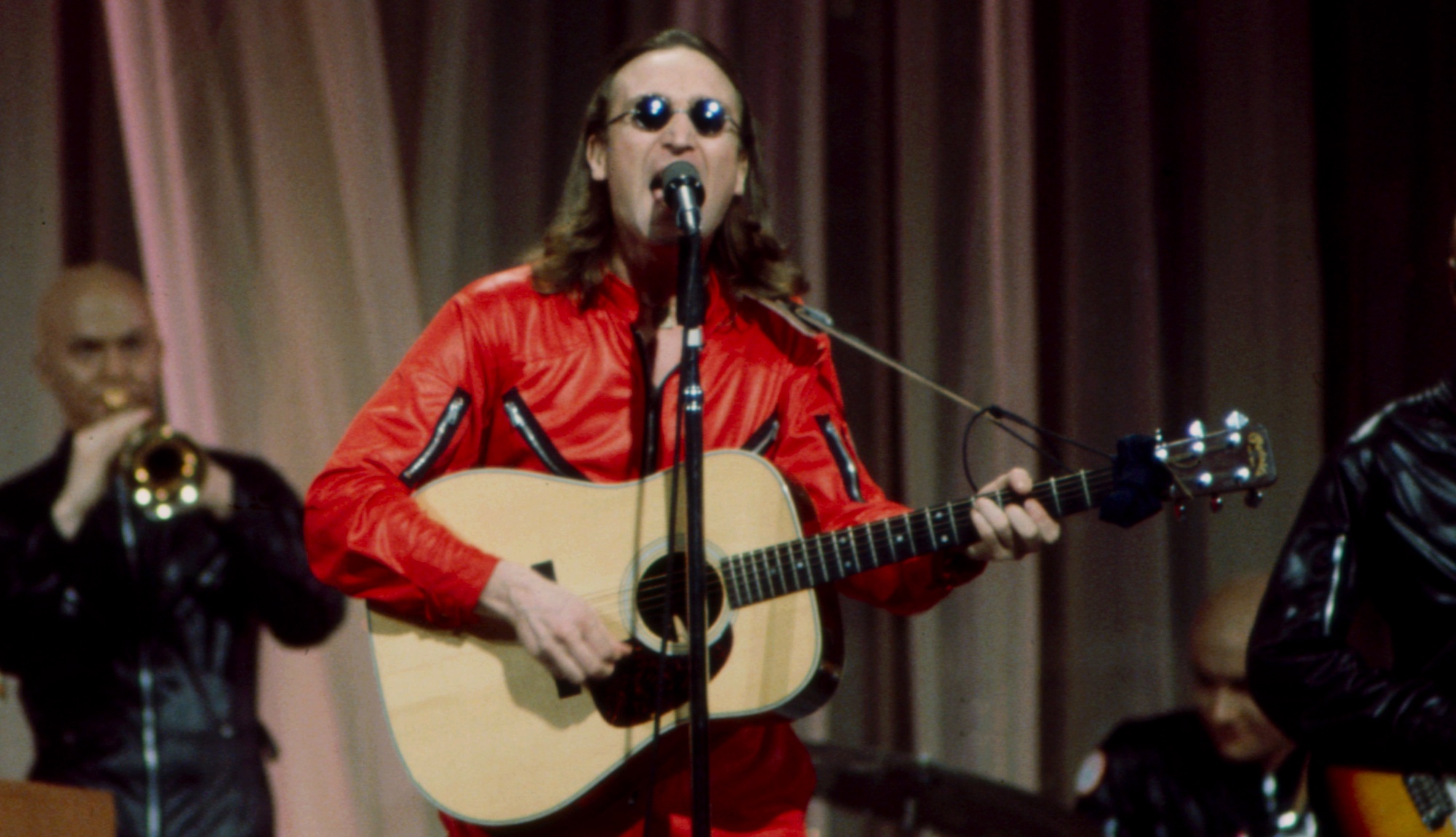

Interview: Black Light Burns Frontman Wes Borland Talks New Album, Gear and Experimentation

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Black Light Burns, the Los Angeles-based quartet fronted by Limp Bizkit guitarist Wes Borland, released their sophomore album, The Moment You Realize You’re Going to Fall, August 13 via Rocket Science/THC Records.

Amid preparation for a fall tour with Psychostick and The Witch Was Right, Borland sat down to discuss the new album, gear, sonic experimentation and a lot more.

GUITAR WORLD: Given your history in visual arts, does music travel similarly through your mind? When writing and producing, what do you see? Math and numbers? Colors and movement?

First, I’m sort of thinking about a lot of different things that have happened in my life as well as different cinematic landscapes or ideas. I’ll think about a lot of things I’ve seen recently, because I am a painter too. I’m always looking at other artists and trying to get inspired by different things. I just collect images from clippings from magazines or whatever.

I’ll sort of think about all of these things and start writing, and I think a lot of these visuals inspire me to think about what those images would sound like. Like, I know how it looks, but how does it sound? And I do that a lot as far as trying to paint things that I hear and make music that I see, I guess.

They kind of go back and forth and cross over into each other. It’s never about math. Ever. I’ve never really been schooled in music theory. I’m a guitar player, and I attack the guitar in a certain way that it not fully unique to me, but it’s more unique that some other people. I’m not a shredder, and I’ve never aspired to be a virtuoso player. I’ve always wanted to be a songwriter and a storyteller and somebody who conveys a feeling to the listener or the viewer.

As Black Light Burns and Limp Bizkit progress, do you find it more difficult to keep stylistic differences separate?

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Not really, especially because they’re progressing further and further away from each other all the time. I feel like Limp Bizkit is going in a direction that allows me to access some wild and experimental elements of myself, but it is primarily aggressive hip-hop/rock/pop music. The feeling of it is more of a party and is, musically, how I’d spend my Saturday night [laughs].

Like if I was with a bunch of people in Manhattan that wanted to go bar-hopping, it’s something I would normally do with Limp Bizkit, but it’s more of a light-hearted good time, whereas with Black Like Burns it’s more so like opening my chest up and vomiting out all of my emotions.

I won’t say Black Light is completely a mourning experience. It’s not a funeral. Our shows are definitely fun, and we are light-hearted about having a good time as far as when we play and put 100 percent into all of our shows. It’s still born out of despair and emotion. That’s the heart of it, and our albums get more and more experimental all the time.

I don’t think it’s hard; I think the first record, Cruel Melody, overlapped a bit with Limp Bizkit, but now if I write something that’s more experimental, I’ll pitch it to Black Light. The same goes for Limp Bizkit if I write something that is a bit more poppy and commercial sounding. Now they are just getting further and further apart.

To have people react to a song and just know it is so flooring. It is such an incredible feeling. It never gets old, either. Even with really old songs with Bizkit. We could be performing some of the first songs we’ve ever written together in front of an audience and have them react, and they’re still like, “Wow.” I’m sick of the song, but they make me not sick of it, you know? It’s like watching one of your favorite movies with someone who has never seen it before.

When playing any song in front of an audience, you’re watching them experience it, and it changes. In a lot of ways, it’s almost like the music is just the background buzz to what’s happening between you and the audience in the room.

What different guitars, amps, effects and various instruments were used for the recording of The Moment You Realize You’re Going to Fall?

We used a 1964 Gibson Thunderbird bass and an Ovation Magnum II, which is one of the only good things Ovation has ever done as a company, and they stopped doing it. It’s a really weird-looking bass, but it’s got a unique sound, and I just love them for some reason. They are really weird, and I guess they were just a failure at the time. I tend to gravitate toward instruments that were failures and that they stopped making because they don’t sound like a PRS or Les Paul. It’s something so different.

For the guitars, I think it was mostly Telecasters for the neck pickup position, a Hagstrom 3, an old Teisco Japanese Jaguar sort of guitar that sounds really nuts and has a bunch of electronic problems but it's really rowdy. I really wanted to make a record that was heavy but not metal. I wanted a lot the heaviness to be in the bass and have the guitars be more of a bite-y rock sound. I think that worked out.

We used a lot of little amps, a bunch of 10-inch-speaker Epiphone and Gibson amps as well as a couple Fender amps. We were using a lot of Zvex pedals that are just kind of unruly and have a bunch of different types of fuzz. We were just experimenting a lot and chaining a bunch of stuff together. One pedal that was really cool was a green pedal called the Bag of Dicks. It actually comes in a paper bag [laughs].

I think I found it at Tour Supply in LA. That thing just generates constant noise if you’re not playing through it. It only had two knobs, gain and volume, but somehow it just had all of these different positions you could put them in that just did terrible things. It was just like, “Why is that happening?” and “I don’t know why it’s happening, but hit record!”

There was a lot of that kind of stuff going on as far as experimentation, but it was really fun. A lot of it is improvised, even to the point of sampling circuit bent toys. We were careful about experimenting. It was controlled and edited. It wasn’t like we said, “Oh, we’re gonna go fart in a buck and record it.”

Many people will argue that anyone can pick up an instrument and learn how to play. You've always incorporated visual aesthetics and unconventionality into your music. How would your differentiate an artist from a musician?

I think there are people who aren’t artists who are musicians, and I think there are people who aren’t musicians that are artists. There are people who are both, but I don’t feel like there are things that are created from musicians. There are people who are amazing violinists, but they don’t really write very much. Or when they do write it all falls into these parameters that they’ve been taught -- sequences. It’s the mathematical thing we talked about. Musicians can tend to get mathematical and just go, “Here you go. Sounds great.”

That works well for scoring film, but I think that a lot of those people don’t have a screw loose, and maybe that’s the difference. Maybe artists have something inherently wrong with their brains and musicians don’t. Artists have this handicap [laughs], and that’s what makes them somehow digest things and spit them out in a way that only makes sense to some people.

Keep up with Black Light Burns at their official website and Facebook page.