James Taylor: “All music is reiteration... We just pick stuff up and use it again. I mean, there are just 12 notes”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Mention James Taylor and most people will instinctively think of his songwriting and singing. His compositions, including Fire and Rain, Carolina in My Mind, Sweet Baby James and Your Smiling Face, and interpretations (You’ve Got a Friend, How Sweet It Is) are imbued deep into the American culture, some of the most-played and best-loved songs of the past 50 years.

But underpinning all of them is Taylor’s fingerpicked guitar playing, which is deceptively complex and completely unique – anything but basic strumming.

Taylor’s self-titled debut album was released in 1968 on the Beatles’ Apple Records; he was the first outside artist signed to the label. To get that deal, he auditioned alone with his guitar for George Harrison and Paul McCartney, both of whom played on the record, which was recorded in the same studio where the Beatles were cutting the White Album.

It’s almost impossible to imagine what all that must have been like for an unknown 20-year-old American.

When that album didn’t become a hit, Taylor returned to the US and started working on his second album. That was 1970’s Sweet Baby James, recorded in less than two weeks for less than $10,000, with Taylor and his band, which included Carole King and guitarist Danny Kortchmar, recording songs as fast as he could write them.

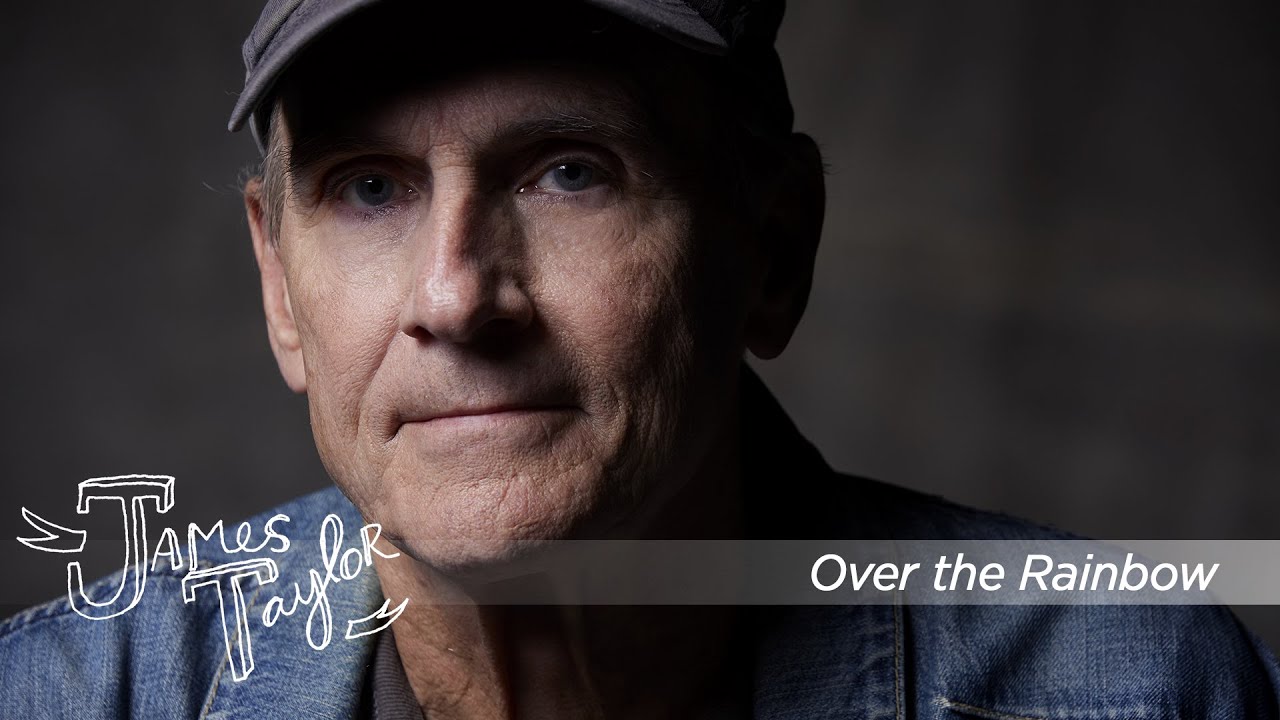

On his most recent releases, 2020’s American Standard and the three-song EP follow-up Over the Rainbow, Taylor focused on songs he learned in his childhood, including Moon River, Somewhere Over the Rainbow and Surrey with a Fringe on Top, mostly performed as guitar duets between Taylor and the jazz great John Pizzarelli.

Your guitar playing is fascinating. It’s very complex, and very different from anything, with elements of Blind Blake and Reverend Gary Davis as well as an almost classical sense of structure and some jazz voicings. How did you come up with your style? What did you pattern it after?

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“Early on, I was very influenced by what my friend Waddy Wachtel calls the great folk scare of the early '60s. It was a great time to be a guitarist and a developing musician; it was so accessible and there were clubs with open-mics and a community of people that played and shared things and were largely self-taught.

Church hymns are really sort of 101 for Western music, and it's a great foundation

“Reverend Gary Davis was huge for me, as well as Joseph Spence, music of the Bahamas. And Ry Cooder, who's still sort of my favorite guitar player. I've emulated him as much as I can.”

There is also a classical sense to your playing, but you never studied classical guitar, did you?

“No, I really never studied guitar formally. The 'classical' thing you’re hearing is actually church music: the Church of England hymnal. Those hymns that I was exposed to in boarding school. We weren't a church-going family, but when I went away to school, I got a big dose of that stuff, and I would transpose them and try to play them.

“Learning to play the guitar by playing those songs was really like a doorway into the roots of Western music. Those hymns are really sort of 101 for Western music, and it's a great foundation.”

Your playing and singing are very aligned and share a powerful rhythmic drive, which is so important for playing solo. Is that something that you worked on intentionally?

“It's something that just sort of develops unconsciously. There comes a point with the guitar when the stuff that's coming back at you is compelling enough that you just want to do it more. At that point, it's like you've started a fire and you don't have to work at it anymore.

“There are periods of time in the songwriting process where you really have to sit down and work, but even that is more of discovery – like channeling something – and it's fun. I have found that as life gets more distracting with family and career and recovery – those are the three things for me – you have no time to write.

“But these sort of seminal or initial sparks of songs, the little pile of dry tinder from which you build a fire, those things still happen on the run. Now I just use my phone and pull over or stop for a second and record a little idea. That process does have a work to it, and as time goes by I’ve realized I have to defend that, to make room for it and make sure that nothing intrudes.”

Your last two releases were collections of standards. Do you have a long history with those songs?

“These are songs that I played in the process of learning the guitar. There are a couple of keyboard overdubs, but it’s basically just me and John Pizzarelli playing my arrangements of these songs. He is a master player, but he was also an excellent editor. Often you want to do a variation of how you support melody in the second verse, for instance, and choose different chords.

“And it was great to bounce those ideas off of John and his help arranging the various iterations of these songs that I've been sort of working with for such a long time.”

Your first album came out on Apple Records. What was the experience like as a young singer-songwriter to sit and audition for George and Paul?

“It was just otherworldly, because I was a huge Beatles fan. And they were at the very height of their powers. They just kept going, kept growing. So, to be in London, the first person signed to their label in 1968, was really like catching the big wave. It was unbelievable.

“I had been in the Flying Machine, a New York band with Danny Kortchmar, and when that crashed and burned, I just decided to go to London. I arrived with my guitar and some songs and no plan at all, beyond trying to get some work in clubs and travel around Europe and see what I could see. I'd met some friends who were very encouraging about my music and got me into a little demo studio I found in the phone book.

“Danny knew Peter Asher, who had a new gig signing acts to Apple and I asked if he thought Peter might be interested in my stuff. And it turned out that it was just the right time.

I had some kind of competence and the arrogance of youth when auditioning for George Harrison and Paul McCartney, without which nobody would ever do anything, because you'd hedge your bets

“Peter and his wife really heard something in my music. And he took me to Apple, where I played for George and Paul. And they said to Peter, you know, if you want to record this guy, sign him to the label. It was that simple.”

How confident were you in terms of your performance and your songwriting when you sat and played for them?

“What a great question! No one ever asks that. I had some kind of competence and the arrogance of youth, without which nobody would ever do anything, because you'd hedge your bets.

“There's a stage in our development where you're allowed to do impossible things, which is why the military looks to people about that age. You can talk people into doing things that if you were asked when you were 35, you'd say, 'No thanks, I'll pass on that.'

“I also knew that it was somehow good. It worked for me, and I was a music connoisseur. I thought, ‘This stuff could go somewhere. I want somebody to hear this.’ I've had that feeling a few times, at different points in my life.”

How did you feel when you heard that George had borrowed the first line of Something in the Way She Moves for Something? Did he ask you first?

“I felt hugely flattered. I had played this song for George and Paul as my audition and I think it had just sort of stuck in his mind. But he didn't realize that. I think all music is reiteration. I think we just pick stuff up and use it again. I mean, there are just 12 notes.”

The song that made you a star was Fire and Rain, which was released as a single long after the album and even after some others had covered it. Did you think it could be a hit, or were you surprised with the reaction?

“Joel O'Brien was the drummer in the Flying Machine and a huge musical influence on me, because he introduced me to Brazilian and Latin music and so much else, but also to heroin.

“He came to London and we were getting into trouble together and I played that song for him. And he said, ‘This is the song that's gonna do it for you. It's really good, and it's accessible. Be careful how you record this one.’ Peter also heard that it was special.

“Both of them probably heard that before I did. We actually did an earlier recording of it, which I've never told anyone because technically it meant that Apple Records should have owned it and I didn't want [Beatles manager] Alan Klein to decide that Fire and Rain was his. That version exists somewhere, but I'm glad that ultimately we cut it as simply as we did.”

The whole Sweet Baby James album is pretty minimalist, which keeps the focus on the songs.

“The thing about it is that we made it for $8,000 on a 16-track recorder in two weeks. They gave us 20 grand to make the album with and on delivery they would give us another 20, which is why one of the songs on the album is called Suite for 20 G. We just amalgamated a bunch of ideas into an album track and put it out because we needed one more tune to finish the album and get our money!

“I can live with a project for a year and get so deep into it that I lose a sense of its purpose – and this was the opposite. We nailed it down so fast. I was recording songs as I was writing them. I'd play a song for Carole King in the morning and we'd go straight to the studio and play it for Danny Kortchmar, and the three of us would put it down with Russ Kunkel on drums.

“We were just living on the surface, like one of those water striders that can walk on the surface tension of a pond. It felt like we were just right on the surface of ourselves and I miss that. We're so careful now and so studious of every move.

“And that's also a good way to record; that's Steely Dan, and Paul Simon, really working the thing and focusing on getting it right. That's another kind of artistic process. But this one was really like stepping out into traffic and getting hit by a truck.”

- James Taylor's latest album American Standard and followup EP Over the Rainbow are both out now on Fantasy Records.

Alan Paul is the author of four books, including Brothers and Sisters: The Allman Brothers Band and the Inside Story of the Album That Defined '70s as well as Texas Flood: The Inside Story of Stevie Ray Vaughan and One Way Out: The Inside Story of the Allman Brothers Band – both of which were both New York Times bestsellers – and Big in China: My Unlikely Adventures Raising a Family, Playing the Blues and Becoming a Star in Beijing, a memoir about raising a family in Beijing and forming a Chinese blues band that toured the nation. He’s been associated with Guitar World for 30 years, serving as managing editor from 1991 to 1996. He plays in two bands: Big in China and Friends of the Brothers (with Guitar World’s Andy Aledort).