Jeff Beck – the ultimate interview: one of the electric guitar's most prolific innovators reflects on his sprawling career

In this classic 2009 Guitar World interview, the guitar legend waxed lyrical on his formative years with The Yardbirds, how his radical technique inspired a new era of instrumental guitar, and his musical relationships with Jimmy Page, Jimi Hendrix and Eric Clapton

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

As we process the news of Jeff Beck's untimely passing on January 11, 2023, we've been digging through the archives to remember some of his best and most thought-provoking conversations with Guitar World. This interview was originally published in the June 2009 issue.

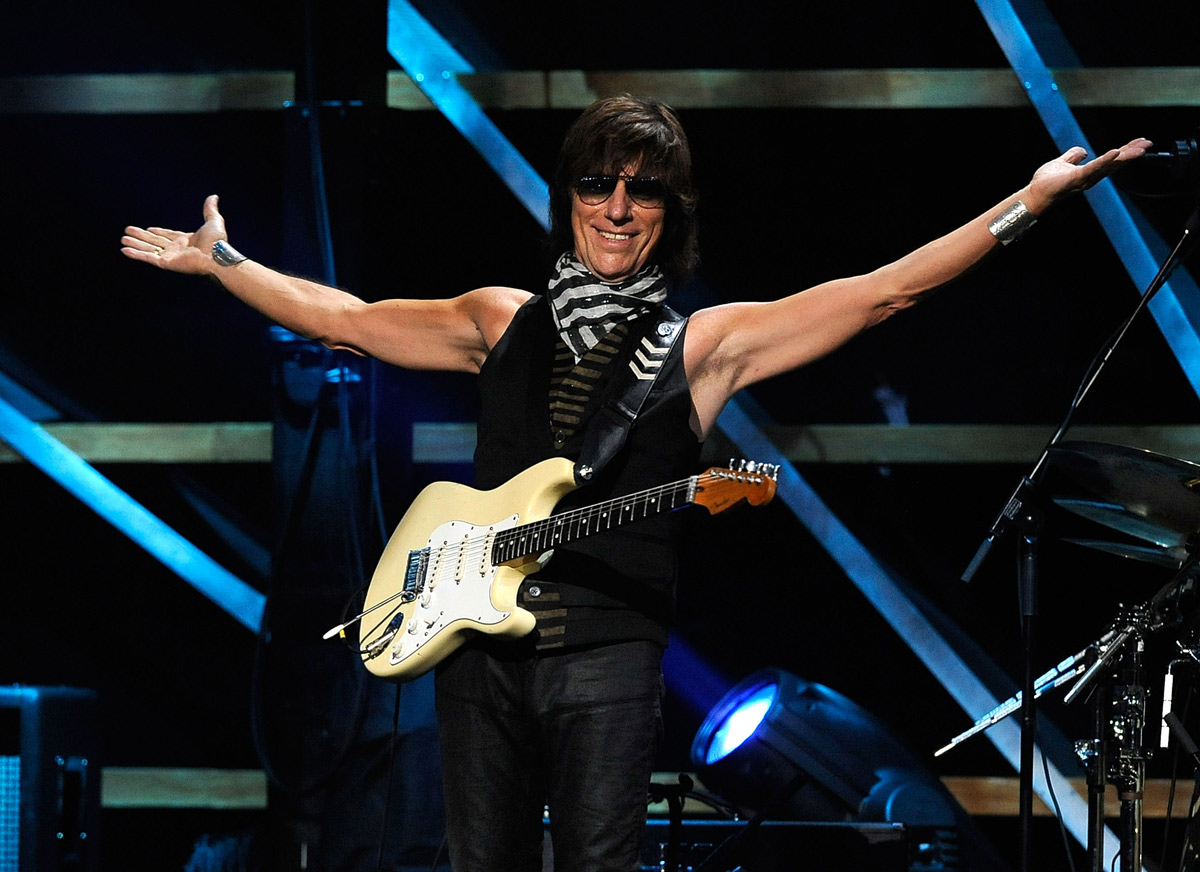

Since starting out with the Yardbirds nearly 60 years ago, Jeff Beck defined guitar virtuosity. On the eve of his 2009 induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, he talked about his storied past, then-recent shows with Eric Clapton and his plans for what would become his 10th album, Emotion & Commotion.

“Largely, I disapprove of overblown ceremony,” Jeff Beck pronounced, referring to his induction into the Rock Hall, “but it’s difficult to say no to something like this.”

It’s an honor more than deserved by the man that many regard as the greatest rock guitarist of all time, bar none. He said, “After 40 odd years, it’s nice to be recognized. It’s nice to know there’s someone ringing the bell for me.”

Back in 1992, Beck had been inducted to the hall as a member of the Yardbirds, the groundbreaking '60s rock band that first brought him to fame and also launched the careers of Eric Clapton and Jimmy Page. But the Yardbirds were just the first chapter in a legend that is as large and bold as rock itself.

Beck was a towering figure in every rock era, deftly moving with the times, yet never pandering to trends. He embraced '70s fusion as gamely as he delved into '90s techno, making each new genre an ideal setting for his dazzling six-string artistry.

“If you look at the albums, I think they pretty much show us the high points,” Beck said of his career. “It’s all the waiting around in between albums that’s never so great!”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

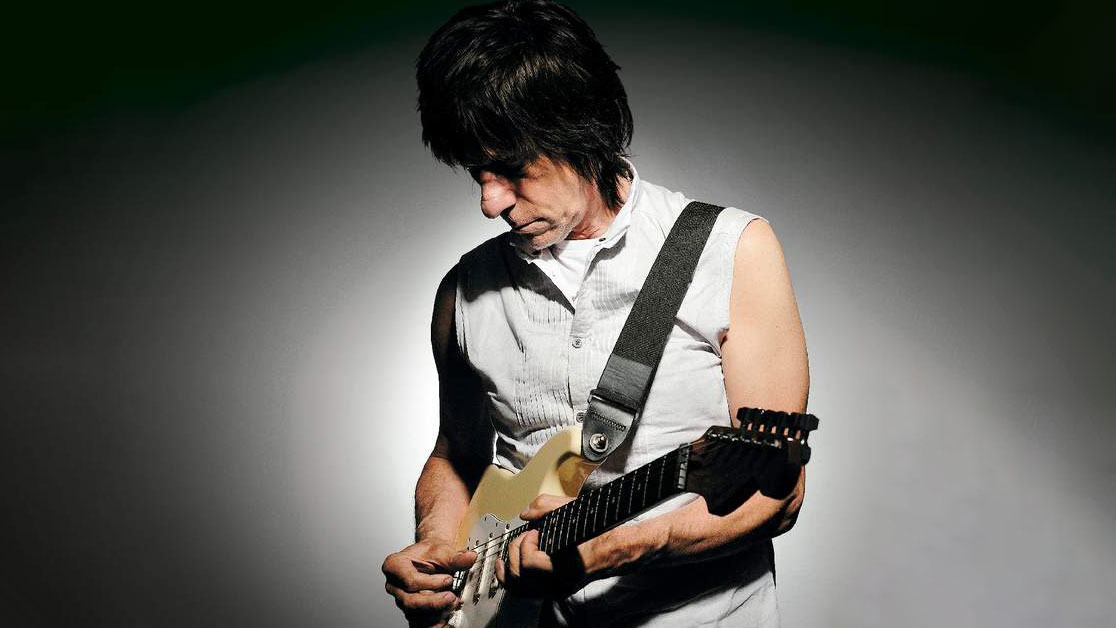

Jeff Beck is entirely in a class by himself as a guitarist. His phrasing is utterly unique – restless, puckish, unpredictable and always a few leaps ahead of even the most adroit listener. Yet he can also touch your heart with some of the most lyrical, graceful and stunningly beautiful passages ever wrested from an electric guitar and amplifier.

Part of Beck’s magic originates in his masterful and mystifying technique. He’s one one of the few rock guitarists that didn't use a pick. All the fingers of his right hand come into play, not only to pluck the strings but also to manipulate the vibrato arm and volume control of his preferred axe, the Fender Stratocaster.

Beck’s uncanny combination of vibrato-arm technique and left-hand string bends have made him a master of legato phrasing and microtonality, the pitches “between the notes” of a tempered Western scale. This renders him better able to evoke the sounds of Indian, Bulgarian and other world music than most other rock guitarists, and adds a mysteriously unique quality to this straight-up rock playing.

Beck’s sense of pitch is more complex and subtle than the average person’s. By not using a pick, the fingers of his right hand are free to roam up the fretboard to execute tapping maneuvers that have all the grace of ballet steps.

It’s a delight to watch how Beck put all these expressive techniques together, and his 2008 DVD/Blu-ray disc Jeff Beck Performing This Week... Live at Ronnie Scott’s provides an ample opportunity to do just that.

Filmed during his week-long residency at London’s legendary jazz club, the disc offers a ringside view of Beck and his band (drummer Vinnie Colaiuta, bassist Tal Wilkenfeld and keyboardist Jason Rebello) performing a set that spans Beck’s solo career. The camera lingers long and lovingly on Beck’s hands as he tears through classics like Beck’s Bolero, Led Boots, Goodbye Pork Pie Hat and Blast from the East. This is guitar porn of the highest order.

“It was nerve wracking, I have to tell you,” Beck says, “because of the low ceilings and smallness of the club. It’s not what we’re used to. We’re used to playing bigger venues. But it was nice to bring some special guests into the performance. We had Imogen Heap, Joss Stone and Eric Clapton, to most people’s delight. It’s nice to have a guest suddenly appear that nobody is expecting to see.”

Those big places, they’re no different to any of the other places once you get stuck into the playing. Except your cash register’s a lot louder

Live at Ronnie Scott’s might never have happened had Beck and his wife not paused for a coffee at a cafe opposite the club one sunny afternoon. They were approached by the club’s artistic director at the time, Leo Green, who said, “Hey, why don’t you play Ronnie’s?” To which Beck promptly replied, “Hey, why don’t you fuck off?” But he eventually relented, cajoled into performing at the club by his wife and also a BBC film crew that was putting together a documentary on Beck and needed some recent footage. He explains, “So we tried to get both things going at once – a bit of intimacy and a bit of footage.”

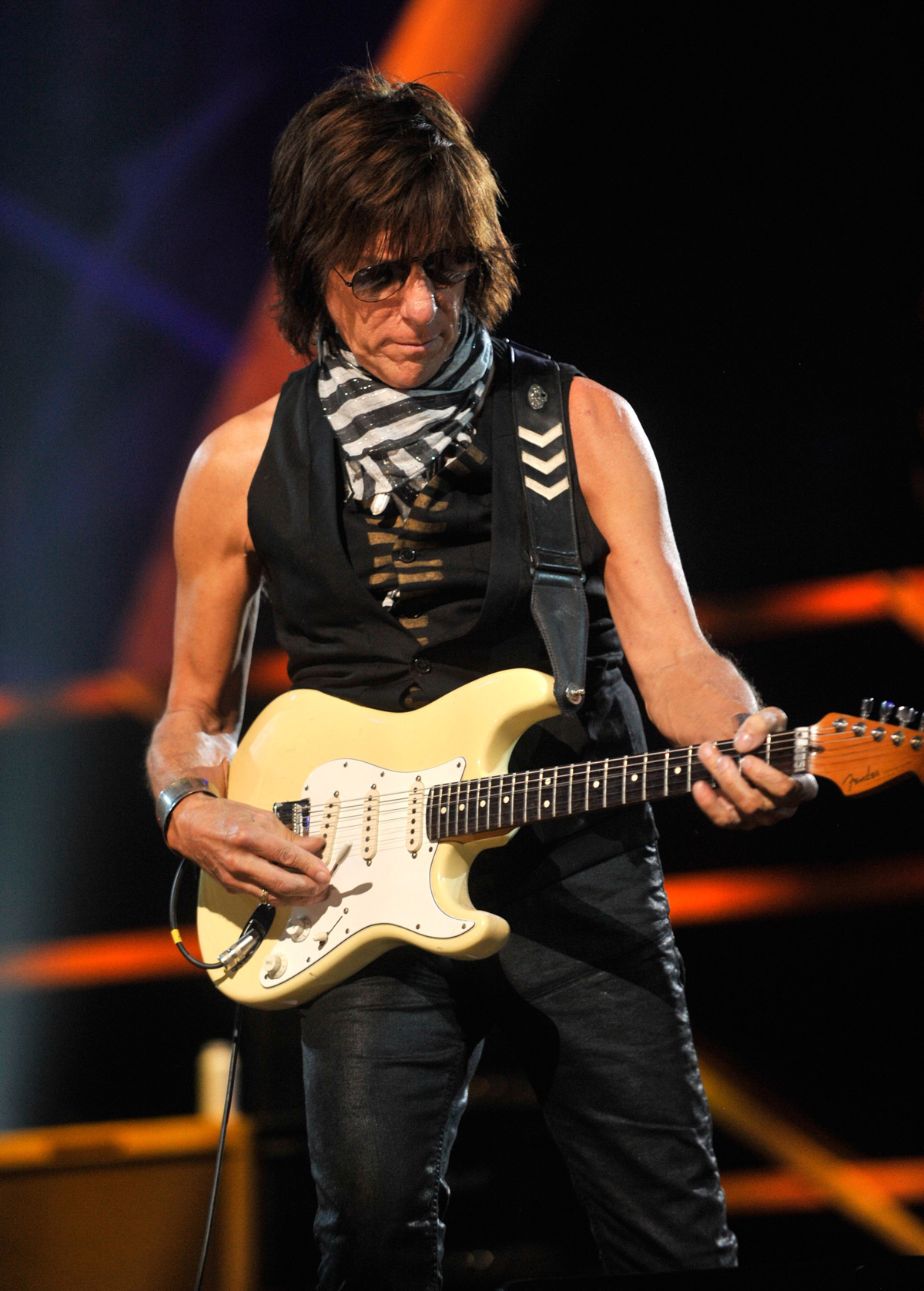

Shortly after sharing Ronnie Scott’s small stage with Clapton, Beck took off for Japan, where he and Clapton performed two history-making live shows together at Japan’s massive Saitama Super Arena on February 21 and 22.

Says Beck, “The Ronnie Scott’s thing was just two songs together with Eric, five or six minutes. But this was a fairly polished 40-minute set, and in front of 16,000 to 18,000 people per night.

“That was an experience – a much bigger place than I’m used to. My usual capacity is 6,000 to 7,000 tops. But those big places, they’re no different to any of the other places once you get stuck into the playing. Except your cash register’s a lot louder.”

The two guitar titans put considerable thought into the setlist. “We had to work pretty hard to get seven or eight tunes that were neutral to both of us,” Beck explains.

“Not too much leaning to one side or the other. Eric suggested a couple of [jazz tenor saxophonist] Eddie Harris songs, which I thought sounded really great. Compared to What was one of them. We also did a couple of Muddy Waters songs. And we ended up with Sly Stone’s I Wanna Take You Higher, which I thought was really great. That was my idea. Eric was most accommodating and very nice to work with.”

So nice, in fact, that Beck says that there are “whispers” of the two guitar heroes reconvening for one or more shows at Madison Square Garden at some point down the road [the pair would go on two play two shows at the New York City venue in 2010].

Meanwhile, Beck has also started work on a new studio album. The guitarist is notorious for changing his mind, but right now what he’splanning is a power trio disc with Colaiuta and Wilkenfeld as his rhythm section.

“I’d like to get back to that Jimi Hendrix Experience type of approach,” he says. “The way that Jimi played, you didn’t miss the keyboards. It was all heavy and powerful. It just suggested power through the drummer, which I like. I love the sound of a big three-piece.”

At this point, Beck’s done it all, as this fascinating career retrospective interview below makes clear. But at age 64, he continues to be a restless musical seeker, never satisfied to rest on his laurels, always eagerly pursuing his next musical incarnation.

No historical account of the guitarist’s highly eventful career can fully sum up the Beck mystique, nor can any technical analysis completely explain his brilliant playing; the magic he works with a guitar transcends both these things. Somewhere beneath that laddish, car-loving, Brit exterior lurks the soul of a poet.

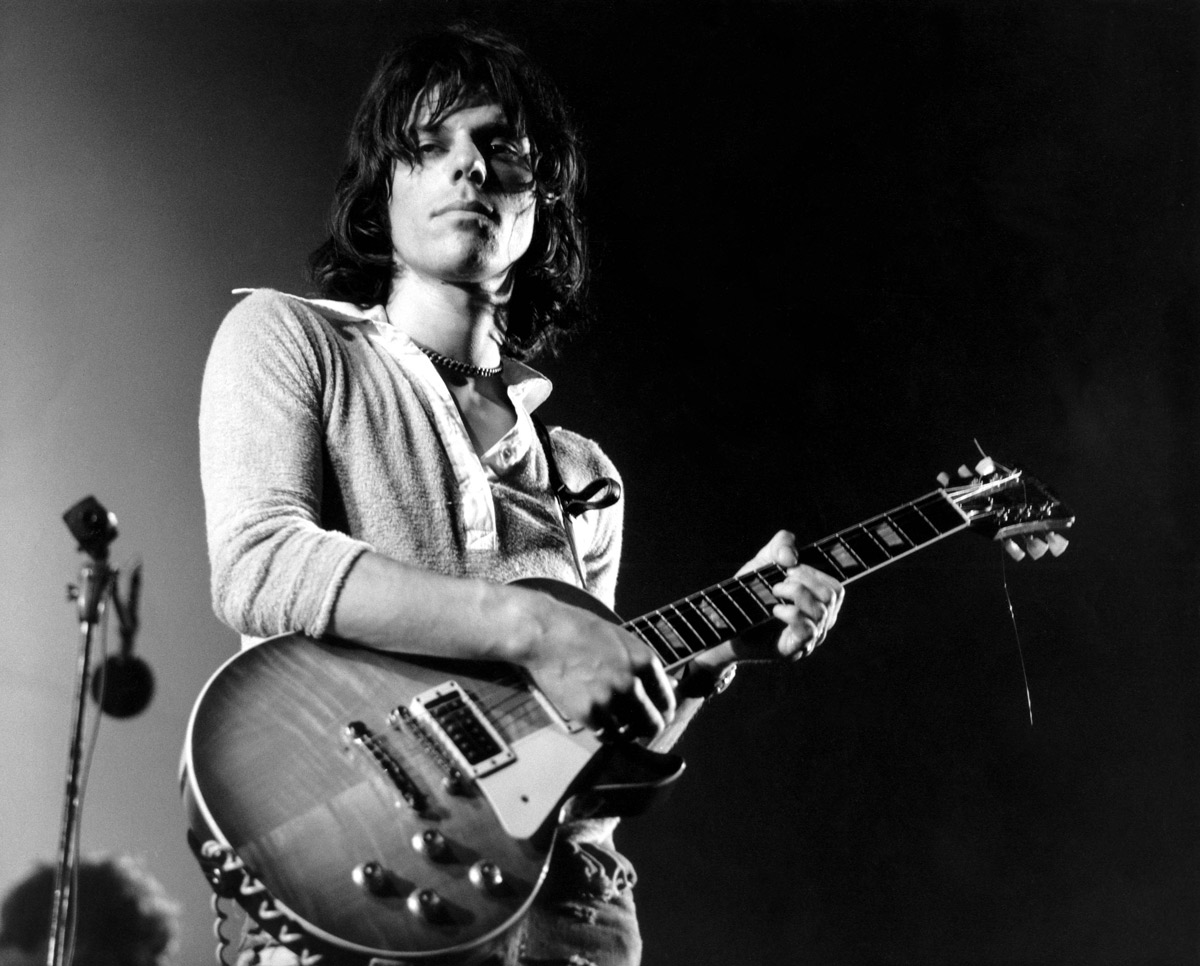

1965-'66: With the Yardbirds

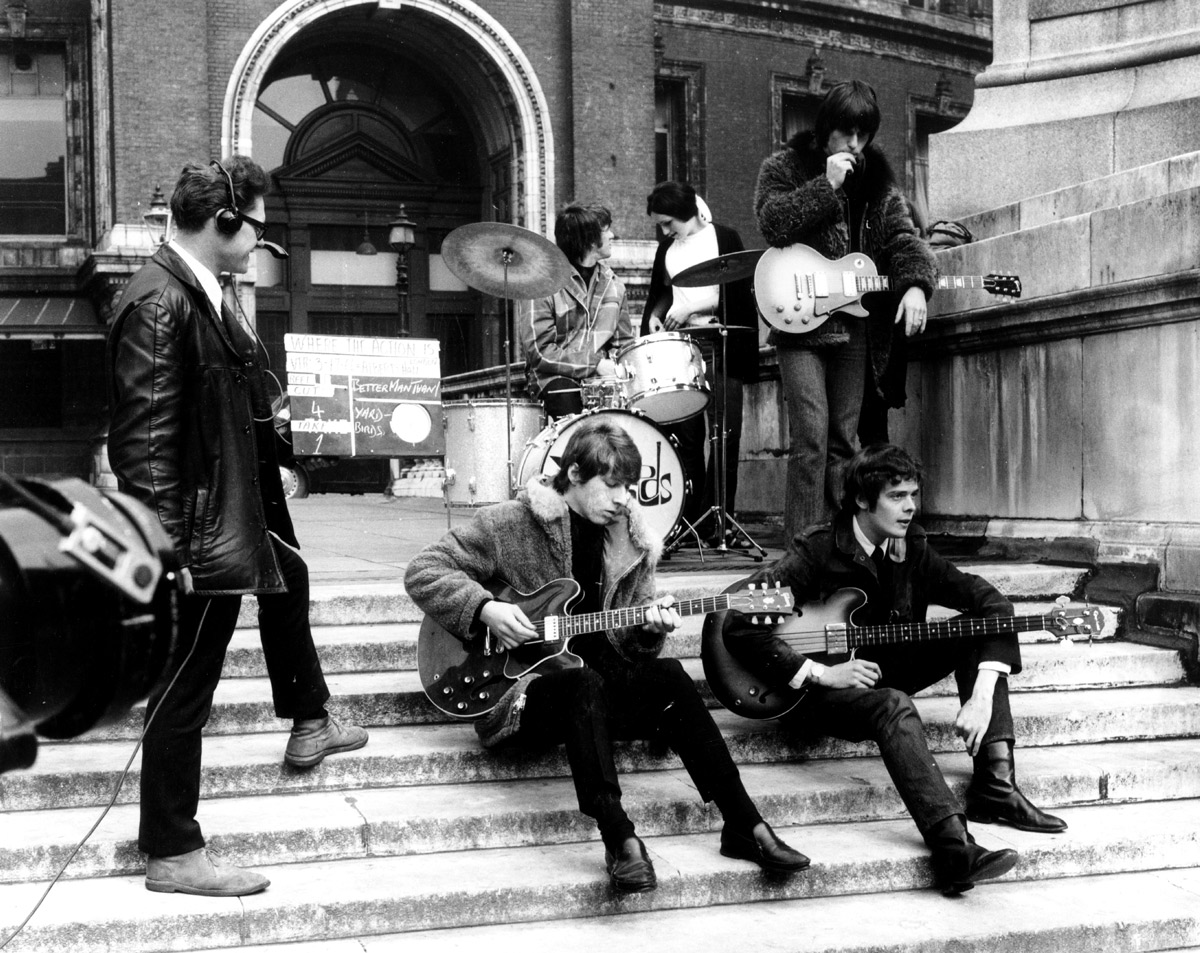

Beck became Eric Clapton's replacement in the Yardbirds just as the group’s career was starting to take off. They were under the enthusiastic, if somewhat journeyman, management of voluble Euro-beatnik Giorgio Gomelsky, who had managed the Rolling Stones early on and also given the Yardbirds the Stones’ old residency at London’s Crawdaddy Club.

Yardbirds’ singer Keith Relf, bassist Paul Samwell-Smith, rhythm guitarist Chris Dreja and drummer Jim McCarty were riding high on the success of their first hit single, the harpsichord-driven For Your Love. But the record had prompted the resignation of Clapton, who was reportedly appalled by the disc’s pop appeal and wished to stick to his blues roots.

Jeff Beck was more open to experimentation. Seasoned by gigs with the Deltones, Tridents and Screaming Lord Sutch, he brought new guitar tones and new musical influences to the rapidly evolving Yardbirds.

His 18-month tenure with them is generally acknowledged to be the band’s most fertile period. Beck’s fiercely innovative playing found the mystical link between blue notes and the plaintive drone of Indian sitar music just coming into vogue in the mid '60s.

I remember having an insulting criticism from Eric Clapton saying, ‘You gotta get rid of that folk style of country picking.’ Probably because he couldn’t do it.

What Beck did with sustain and vibrato seemed like voodoo in 1965. Brilliant Yardbirds singles like Heart Full of Soul, Evil Hearted You, Shapes of Things and Over Under Sideways Down drew up the blueprint for psychedelic guitar rock. The authoritative bite of Beck’s Fender Esquire on bluesier Yardbirds numbers like I’m a Man, and Train Kept a Rollin’ left an indelible mark on American garage rock.

Suffice it to say that the Yardbirds were the first rock band where the guitar playing mattered more than the singing. The nervous energy of Beck’s guitar lines – terse phrasing and vertiginous leaps from the top of the fretboard down to the low strings and back again – make his Yardbirds-era guitar work distinct from that of Clapton and Jimmy Page.

It was Beck who brought Page into the Yardbirds. (Ironically Page had been offered the gig after Clapton left, but declined, recommending Beck instead.) The two guitar titans played side by side for a handful of Yardbirds gigs and three recordings (Happenings Ten Years Time Ago, Psycho Daisies and Stroll On). But then Beck left the group that had brought him worldwide acclaim, his mental and physical health undermined by the Dickensian rigors of mid-'60s touring.

You’re one of the few rock guitarists who picks with his fingers instead of a flat plectrum. Is that something you got from your early interest in country-influenced rockabilly players?

“Absolutely. From Cliff Gallup [guitarist in Gene Vincent and the Blue Caps] and Chet Atkins. I was fascinated with how Chet Atkins played a bass part and the melody simultaneously. I had to learn that. It helps the brain with coordination to keep a rhythm going with claw-hammer style [picking]. It all comes from folk banjo and God knows what else.”

Is it fair to say that your rockabilly influences set you apart from many of your blues-purist contemporaries, like Clapton and the Stones?

“Yeah. I remember having an insulting criticism from Eric Clapton saying, ‘You gotta get rid of that folk style of country picking.’ Probably because he couldn’t do it. I know it used to annoy him. I’d be out in the middle of some simple groove and then out would come this claw-hammer picking. I felt like doing it, so I did.”

I did feedback way before Clapton, probably in 1960, with the Tridents, because I had a terrible amp that fed back anyway

So who was doing feedback first? You? Clapton?

“No, I did it way before Clapton, probably in 1960 [with the Tridents], because I had a terrible amp that fed back anyway. And when we started playing big ballrooms you’d turn up the volume, and [the amp would] wheeeee. And everybody would start looking at me, thinking I wanted to be dead ’cause I’d made this mistake.

“So I had to turn a horrible sound into a tune to make them think I meant it. That’s where it all came from: the inability of sound systems to cope with the needed volume. We had no real PA. The singer would use the house PA, with a terrible microphone. One of those little square things that was all bass and nothing else.

“And then, of course, the Yardbirds enabled me to continue experimentation. That’s why I really enjoyed that time. Keith Relf and Paul Samwell-Smith used to write these very skeletal kind of melodies that enabled me to do tricks that I otherwise probably wouldn’t do. All I needed was three good melodies, and away I went.”

Speaking of great guitar melodies, did the Heart Full of Soul demo arrive with that intro riff in place?

“No. I don’t think so. It was written by Graham Gouldman [later of 10cc], who also wrote For Your Love. And [The Yardbirds] got this Indian man in to play sitar. But the sitar player we got couldn’t play in 4/4 time. What he was doing was totally magical, but it just didn’t have any groove to it.

“And I showed him on guitar what I thought would be a good idea, which was that minor riff with the D string droning an octave below. And everyone said, ‘That sounds great. Let’s just leave that.’ And we sent the Indian man on his way. But the riff wasn’t there before. It wasn’t written like that. I could be wrong, but I just don’t remember that that had already been written.”

You played a Fender Esquire in the Yardbirds?

“Yeah. Except for some of the later recordings, where I used a Les Paul.”

What about amps during this era?

“Two Vox AC30s, linked in series and placed on two chairs that were commissioned from whatever sources. So they were at waist level, where I could get to the controls easier and hear the sound better.”

Were things like the incredible guitar solo in Shapes of Things rehearsed or pretty much done off the cuff?

“Off the cuff. I remember there was mass hysteria in the studio when I did it. They weren’t expecting it. It was just some weird mist coming from the East out of an amp. Giorgio Gomelsky was freaking out and dancing about like some tribal witch doctor.

Was there a groupie scene back then?

“Yeah. And some of them were pretty memorably horrible. I think they were going in for a huge arse contest or something. Badly camouflaged.”

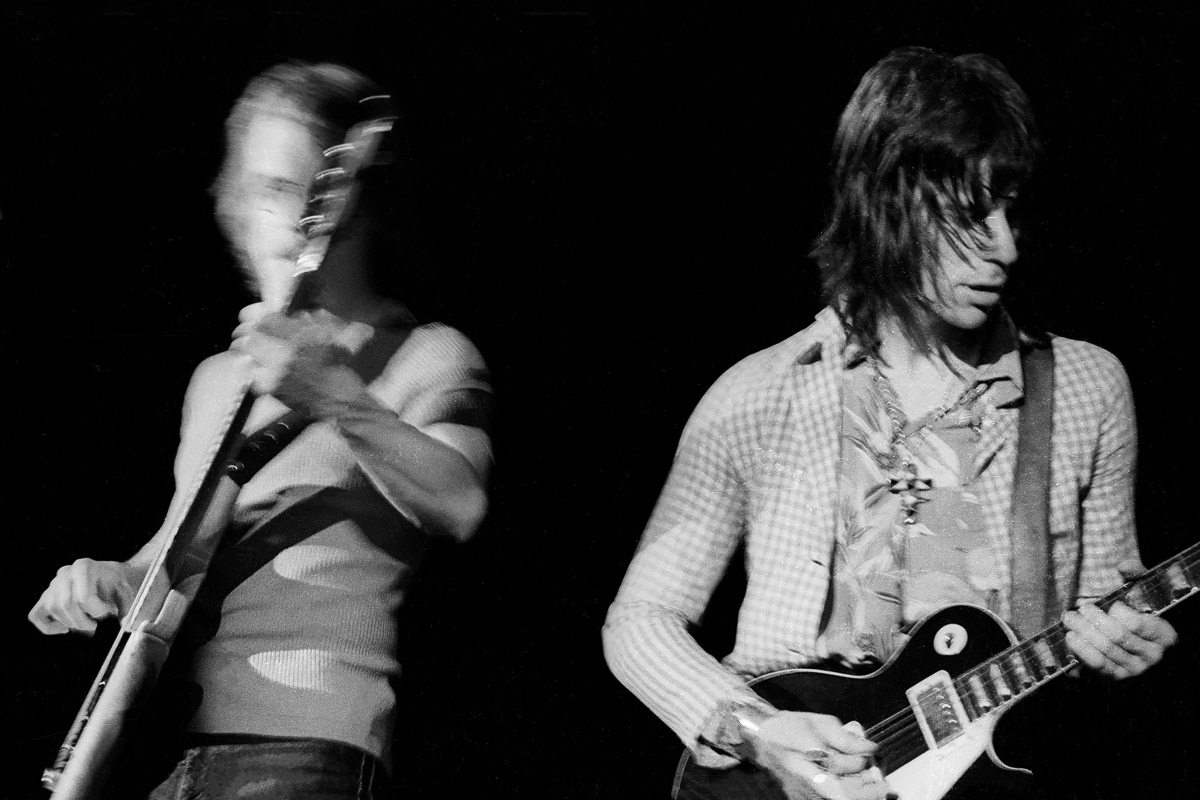

You had actually asked Jimmy Page to join the Yardbirds before Paul Samwell-Smith left, hadn’t you?

“Yeah. And then when Paul did leave it was quite a blow, because we didn’t have that huge bass sound – ’cause he pioneered those four-note bass chords. Jim [Page] was not a bass player, as we all know, but the only way I could get him involved was by insisting that it would be okay for him to take over on bass in order for us to continue. And gradually, within a week, I think, we were talking about doing dual leads. Then we switched Chris onto bass to get Jim onto guitar.”

![[L-R] Jimmy Page and Jeff Beck](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/dJWq93XninyqMrc47ZWEn6.jpg)

How long have you known Jimmy Page?

“We must have been 12 or 14. My sister gave me the introduction. She went to the same art college, or tech college, whatever it was. She came home and said, ‘There’s a guy with a goofy-looking guitar like yours at college.’ And I went, ‘Where is he? Take me to him!’ And we’ve got on well ever since.”

It’s said that Page first played guitar in the Yardbirds because you collapsed in San Francisco and he had to cover on guitar while Chris Dreja switched to bass.

“Oh, I can’t remember. I collapsed everywhere, didn’t I? Yeah, it was terrible. I also collapsed in Marseilles once with food poisoning. Obviously, the idea of having Jim and me on guitar was a great one, but it was fraught with disaster because, sooner or later, one of us would have been cramped, style-wise.

“I don’t know – maybe we would have worked something out. But I said, “Wait a minute. I just got my best mate in on guitar. He’s gonna see me off up the road if I’m not careful.”

Was that part of the tension that led you to quit the Yardbirds in 1966?

“No, it was really just those package tours that got me down. When we were alone it was alright, but banged up with 15 other acts it was really dreadful: onstage for 15 minutes, then you’d drive 600 miles and do another 15 minutes – I couldn’t stand it. I just got off the bus and literally went home.

“I loved being in that band, but I could see the end in sight anyway. So it was that, coupled with the rigorous touring. Being misrepresented. Being put on Dick Clark roadshows and stuff was not where I wanted to go. [The tour Beck abandoned was with teen-oriented pop acts Brian Hyland, Gary Lewis & the Playboys and Sam the Sham & the Pharaohs, hosted by American DJ and TV presenter Dick Clark.]

“But it was still traumatic leaving the Yardbirds. Because I just walked out on the one thing that gave me life, gave me recognition. It was pretty tough. I didn’t feel proud about dumping them in the shit. I got home and faced a bleak winter in England with nothing to do. So I must have been desperately unhappy to do what I did.

“I guess I thought they were going to call me up when they came back and say, ‘Sorry we upset you. Please come back.’ Instead, it was more like, ‘Sorry we upset you. Fuck off.’

“Then I got seriously ill several months afterward. That food poisoning in Marseilles took care of me big time. I couldn’t get my strength back. I think it was a lot more serious than it was diagnosed. It was more like a meningitis type of headache. Terrible. So silly was the pain, I just felt somebody must be able to hear it. It was that bad. I don’t think I was given the right medication.”

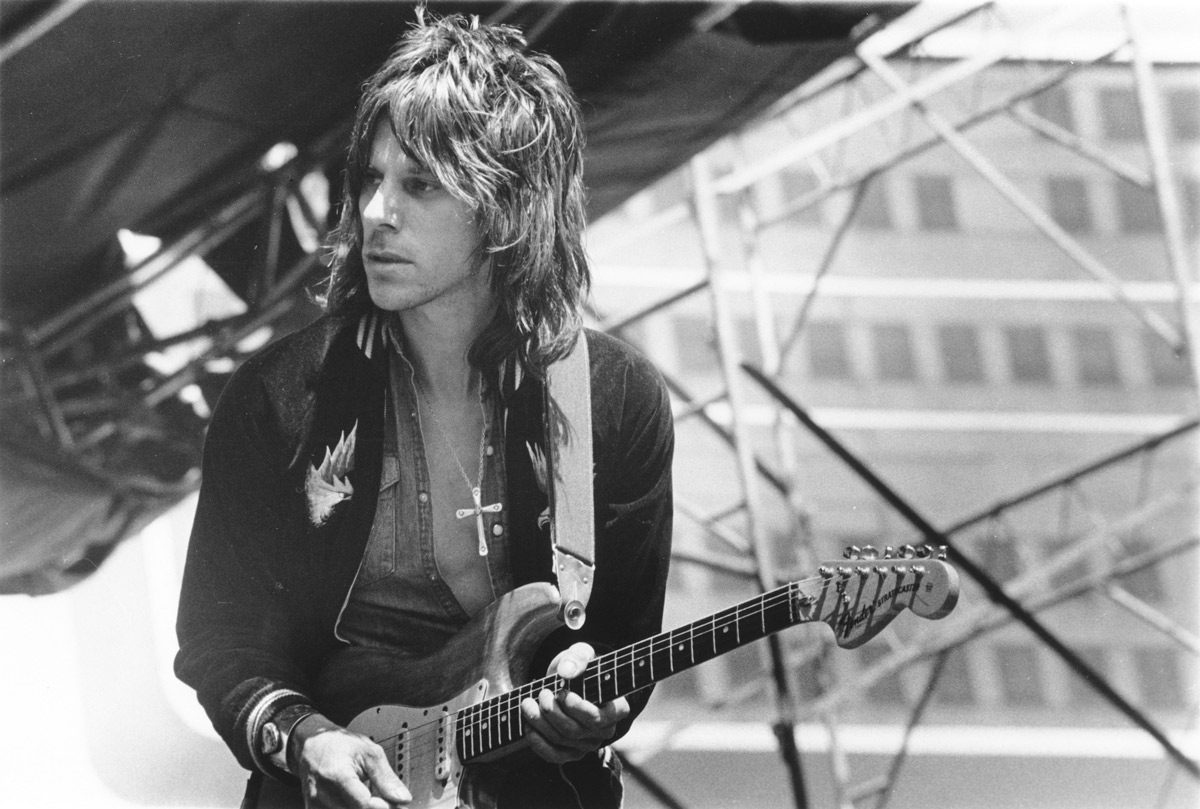

1967-'69: The Jeff Beck Group (Mark I)

Regaining his health, Beck entered the era of the power trio in grand style. The Jeff Beck Group took its place alongside Cream, the Jimi Hendrix Experience and Led Zeppelin at the vanguard of bands that were defining the late-'60s guitar rock aesthetic: a heavy sound, with plenty of room for extended, freeform improvisation.

Vocals were provided by Rod Stewart, soon to be lead singer for the Faces and, later, a superstar on his own. Ron Wood (later of the Faces and Rolling Stones) was on bass, having switched over from guitar at Beck’s prompting.

The drum throne was occupied, at various points, by Mick Waller, Tony Newman and, for the one fabulous studio cameo, the Who’s Keith Moon. Also lending a hand – two, actually – was session pianist extraordinaire Nicky Hopkins, whose nimble playing was integral to many of the best tracks by the Stones, Who and others.

This was Beck’s Les Paul–through-a-Marshall phase, and signature tracks like Beck’s Bolero found the master experimenting with chunky, guitar harmonies. An unlikely alliance with producer Mickie Most, best known for his work with British Invaders like the Animals and Herman’s Hermits, yielded two all-time classic albums: Truth and Beck-Ola.

A solid fave with late-'60s groupies, the Jeff Beck Group had superstar potential. But alas, tensions between Beck and Stewart brought the band to an early demise.

How did Mickie Most end up being your producer after you left the Yardbirds?

“That was as absurdly ill-advised a career move as it was quirky – as traumatic as it was useful. Mickie was a complete bubblegum, middle-of-the-road producer, but he still loved Motown and rockabilly – he just wouldn’t have anything to do with them at the time.

“He was a forward-looking pop producer, and he had good-quality acts like Donovan, Lulu and all those, who were annoyingly good at selling records. [Beck played on Donovan’s 1968 single, Barabajagal.]

“But where Rod was concerned, Mickie told me, ‘You don’t want that poof on your record.’ And that’s where I started to hate him. I said, ‘You, in your infinite pop wisdom, can’t see that this guy’s gonna rule big-time?’

In ’67 and ’68, when I was in big trouble with my musical career and wondering what direction to take, Mickie Most explicitly said to me, ‘Oh, that Jimi Hendrix and all that twang-twanging and feedback nonsense – it’s finished.’ I said, ‘Excuse me, it’s just starting’

“He also couldn’t see a market in America for underground, sort of hooliganistic rock. In ’67 and ’68, when I was in big trouble with my musical career and wondering what direction to take, he explicitly said to me, ‘Oh, that Jimi Hendrix and all that twang-twanging and feedback nonsense – it’s finished.’ I said, ‘Excuse me, it’s just starting.’

But Mickie’s sidekick was Peter Grant [who went on to manage Led Zeppelin]. And finally Mickie said, ‘I’ll tell you what I’ll do: I’ll introduce you to my partner next time you come up. I don’t want to know from you anymore. You finish the contract, you do what I say, and we’ll all be happy. If you want to be on TV, you do the songs I want. And you sing.’

“He couldn’t see that the guitar was what I should be doing. But Peter Grant did. And it was just that thread of lifeline that got us to America with Rod. Peter Grant believed in the act.

“I damned and confounded New York when I came back with that band. All the bad reviews about me being a bad boy leaving the Yardbirds in the shit were all just washed away when we played the Fillmore East. Don’t get me wrong – we were shitting our pants. Rod wouldn’t come and sing to the audience direct; he was hiding behind some curtains. I finally had to say, halfway through the set, ‘There is a human actually making those noises in this building.’”

Why did you decide to recut the Yardbirds’ Shapes of Things with the Jeff Beck Group?

“Because Rod loved that song. He thought it would be a great idea to do another angle on it, and I just wrote that complete other riff for it. And it became the precursor to a lot of power rock and roll. That plodding sort of rhythm that we nailed. I suppose whenever I get named as a heavy metal innovator, that’s probably one of the best examples of heavy metal in embryo.”

Mick Waller’s drum work on that was incredible.

“He was great. For a long time he was flatmates with a Motown drummer, Benny Benjamin, which must have rubbed off, because he had great dexterity and fantastic Motown chops. Unfortunately, having seen Keith Moon, I just couldn’t be happy unless I had a drummer with that amount of charisma and power. Mickey was a great drummer, but he didn’t have the charisma.”

You were close to Keith Moon?

“Yeah. I couldn’t get enough of him. A day would go by in half an hour when you were with Moonie. Just complete lunacy and genuine organic humor. Your jaw would ache from laughing. How [The Who] put up with him for as long as they did, I’ll never know.”

He’d come onstage and completely overshadow and undermine what we’d done. But nobody cared; it was so great

And he’s on Beck’s Bolero.

“Yeah. We couldn’t mention him on the album for contractual reasons.”

Did Jimmy Page write that song as a vehicle for you?

“No. It was my melody over his rhythm. He came up with the bolero rhythm on the 12-string. But it’s my riff in the middle. I’d decided that the Yardbirds’ trademark was to stop in the middle of the song and come into a completely different rhythmic thing, like they did on For Your Love.

“A pop single that suddenly stopped and changed groove halfway through just broke all the rules. So with Beck’s Bolero, we used that as a kind of signature, to continue that kind of raw break.”

This is also the period when you got to know Jimi Hendrix.

“You say, ‘know Hendrix.’ It was all too brief. It was just one year – ’69 it would have been – when the Jeff Beck Group was playing [Manhattan rock club] Steve Paul’s Scene. We were there for weeks, and Jimi would come in just about encore time and everyone would freak out.

“He’d come onstage and completely overshadow and undermine what we’d done. But nobody cared; it was so great. And to have Rod singing as well, two guitars blazing away… forget it. It was just crammed to capacity every night.”

Did playing with him goad you to whip out some of your most amazing stuff?

“Yeah. I thought, if he’s not afraid to stand onstage with me, I’m not ashamed to go anywhere. There was such a contrast between the way he was onstage and the way he was offstage. He spoke in whispers. He would never raise his voice above a whisper. It was all in his expressions, in the hands. Unbelievable comedy and profound statements just by the raising of an eyebrow.

“He did burn the candle, though. I couldn’t keep up. We went out one night, from the Scene. We’d already played two hours of raving rock and roll with him coming on for the encore. Then we went to the New York Brasserie to have something to eat, and somewhere after that. At four o’clock he said, ‘Let’s go back to the hotel.’ I thought, Thank God. He’ll fall asleep and I’ll go off home. But instead he’d start playing stuff, and we’d go out somewhere else at five o’clock.

Suddenly this guy comes along and upturns the whole applecart – playing with his teeth, behind his head… He made the rest of us look like a bunch of librarians standing up there

“This was just an everyday occurrence. I’d be history for two days afterward, and he’d be still at it. The guy was on a big-time roll. It was as if he’d been commissioned to be Chief Motherfucker in charge of everything.

“Suddenly this guy comes along and upturns the whole applecart – playing with his teeth, behind his head… He made the rest of us look like a bunch of librarians standing up there.”

But he was definitely building on what you, Clapton, Jimmy Page and Pete Townshend were doing.

“That’s right. We just didn’t realize that someone was going to come along and whip the carpet out from under us in quite such a radical way. And there wasn’t any turning back after that. You can’t unpull the carpet; you just do something else.

“That was the most ponderous time in my life: what to do now that that guy’s done what he’s done? And when I found out that people still wanted to hear what I had to say, I carried on.

“But it was pretty rough, I must say. A pretty grim time, with no one to talk to about it, except Jimi himself. It was almost the end of my career. I probably would have packed up if he hadn’t spoken.

“I used to say ‘Jim, what the fuck?’ And he said. ‘Man, you know when you play blues, it’s as boring as a monkey. Your next step should be to take the electro stuff further. Experiment. That’s what I respect about you. That’s your thing. Don’t try to play the blues.’ And that’s with Eric as well. He said ‘Don’t mess with my music.’ So I forgot about the blues…with a few notable exceptions.”

So why did the first Jeff Beck Group break up?

“Unfortunately, we didn’t have enough material to keep that band going. Rod was writing ghastly lyrics, just thrown together. It’s a shame, because I thought he was singing really great on Beck-Ola. We should have had a writer or producer come in and take over. Rod’s attitude was, ‘I don’t like being a sidekick to a guitar hero.’ Quite right. Tough shit, mate. See ya.”

I was going to ask what your original concept was in naming the band the Jeff Beck Group.

“Well, I was the name, you know? Because of the Yardbirds. I couldn’t really hide behind Rod and expect anyone to book us. I didn’t like the word ‘group.’ I suppose it was supposed to be like The Spencer Davis Group, where Steve Winwood was the main vocalist. That worked for them, so what about the Jeff Beck Group with Rod as the main vocalist? He didn’t like that at all. There was sour hatred and resentment for having my name on the tickets and yet he was singing.”

1970-'74: The Jeff Beck Group (Mark II), and Beck, Bogert & Appice

In 1970, recovering from a severe automobile accident, Beck put together a new version of the Jeff Beck Group with drummer Cozy Powell, bassist Clive Chaman, keyboardist Max Middleton and vocalist Bobby Tench. Together, they cut the Rough and Ready album.

“I feel like I wasn’t there for that one really,” Beck says in retrospect. “It’s a post–car crash album. Rod wasn’t there. It was like, ‘What do we do?’”

A second album, titled Jeff Beck Group but widely known as “The Orange Album,” was produced by guitar great Steve Cropper and included the jam-night perennial Going Down.

Beck’s next project was a band with American bassist/vocalist Tim Bogert and drummer Carmine Appice, formerly of Long Island, New York’s Vanilla Fudge and Cactus. The Beck, Bogert & Appice album included a heavy rock version of Stevie Wonder’s song Superstition, a tune that Wonder originally wrote for Beck. It was the first of several Stevie Wonder songs that Beck would cover.

One of your more surprising career moves was playing with Tim Bogert and Carmine Appice.

“You think that was surprising?”

Yeah. Here were these American guys, from a different world, musically.

“It was like I said about Moonie. I was trying to get a drummer that seriously kicked ass. I was looking for that kind of over-the-top awesomeness that Keith had – the stick twirling and everything. And Carmine did it. He was really devastatingly good. Carmine was probably the last of the Forties-style, bigband, fuck-off drummers.

“Yet he still had that forward-thinking Billy Cobham–type feel. But once again, we had more power than we needed but not enough of a story line, so to speak. Not enough good songs; great actors but no storyline. Although that seems to sell millions of dollars worth of films nowadays.”

Stevie Wonder’s music became a big inspiration for you around this time.

“Absolutely. Hearing Music of My Mind just really moved my spirit. I was at someone’s house; I picked it up and played it. I couldn’t hear what they were saying for an hour. I was just completely mesmerized by the sounds coming off that record.

He put me on one of his songs on the Talking Book album, Lookin’ for Another Pure Love. I couldn’t care less if the solo stank. Just the way he said ‘Do it, Jeff!’ on the record, that meant a million quid to me

“And I thought, There he goes – there’s a genius reinventing himself. And the thought that I’d be standing next to him in the studio one day was way beyond my dreams. But right out of the blue, after having raved about that record, it must have reached somebody at Epic. And they said, ‘Stevie would be interested in having you go over.’

“And I sort of went…gulp. It was the most memorable time. Frustrating at first, because you know he can’t see you – there’s this immediate barrier right there. But within a couple of days that was gone. It was really uplifting just to be around and watch him put a song together so quickly and so perfectly that nothing could be improved.

“He’d do a rough tryout of something that was better than anything I could ever come up with. He was someone with songwriting skills unknown to me before. I thought, I just better stick around here for a couple of hours.

“And he put me on one of his songs on the Talking Book album [Lookin’ for Another Pure Love]. I couldn’t care less if the solo stank. Just the way he said ‘Do it, Jeff!’ on the record, that meant a million quid to me.”

But you never had the opportunity to record with him again?

“There was another one he wanted me to go on, but I was too out of it to play. A bunch of us dropped by [New York City recording studio] the Hit Factory one night when Stevie was there.

“But we’d really been out on the, uh, cold drinks, so I declined his offer to play. I couldn’t bear to disgrace myself in that state. I was pretty bad. We really could put it away. I said I never did take drugs, but we did lube up occasionally.”

1975-'77: The Fusion Years

In 1975, Beck announced that he was tired of working with vocalists. Energized with the jazz fusion movement, which had taken a foreground role in the mid-'70s music scene, Beck began work on an all-instrumental album with Beatles producer George Martin at the controls.

The result was the brilliant Blow by Blow, one of the best-selling instrumental records of all time and probably Beck’s best-known album.

Beck delved even deeper into the fusion scene the following year on Wired. He augmented the Blow by Blow lineup (keyboardist Max Middleton, bassist Wilbur Bascomb and drummer Richard Bailey) with two key members of John McLaughlin’s Mahavishnu Orchestra: synth-wiz Jan Hammer and drummer/producer Narada Michael Walden.

A lot of people liked Blow by Blow because it simplified McLaughlin and it complicated rock and roll. That album was just one of those things that was so easy

Hammer’s innovative Moog lead lines provided an excellent foil for Beck and coaxed new shades of timbre and phrasing from the guitarist’s manic sensibility. The two virtuosi went on to release Jeff Beck with the Jan Hammer Group Live in 1977.

You’ve always moved with the times and worked in whatever the current musical idiom was at any give time, whether it was heavy rock, fusion…

“Can we say that word now and get away with it? Can we say ‘fusion’ without getting arrested? [laughs] When I first heard the Mahavishnu Orchestra, playing in Central Park, I just began to develop wings because of that. They were hugely popular at that time, and it seemed to me that everyone was getting so involved in, and so in love with, playing music. It was a vital thing for me to have that.

“A lot of people liked Blow by Blow because it simplified McLaughlin and it complicated rock and roll. That album was just one of those things that was so easy. There were great players, willing to play, and decent material. And in four days we’d tracked all the songs.

“Of course, the overdubs then took four years, but the tracking was really quick. For one, we didn’t have a huge backlog of dough. And George Martin certainly didn’t know what he was getting involved in. I put some tapes on his desk one day. He saw through the mist and said there might be something there. He showed interest at a point where I was really wondering whether I should continue in the business.”

How would you assess George Martin’s contribution to Blow by Blow and Wired?

“I was looking to George sort of as a parental figure: someone to help me present some of my more outrageous visions in a way that would be acceptable to the general public. And he did it quite well.

“Some of my favorite solos got trashed because he thought they were hideous – not musical. He’d say, ‘That’s really the most dreadful noise I’ve ever heard.’ And I’d say, ‘That’s what I want!’ But I’d usually come ’round to his way of thinking.

“George is almost like a dad: relaxed, very focused on the sound. George Martin was probably the best producer I’ve had – the guy who could framework what I do without interfering.”

Tonally and melodically, your playing entered a new phase with Blow by Blow.

“Well, Blow by Blow is when I started messing with the Strat. I thought, I can’t be dicking around with a lot of different guitars, ’cause it was a totally different feel from one to the other. I wanted to be absolutely comfortable. And the Strat is what I started on. I became interested in going back to that again.”

Actually, I hate Freeway Jam! It’s pretty awful. I could care less if people still like it. It felt like a slowed-done Irish reel to me

Freeway Jam became one of your signature tunes, one that almost every guitarist learns at some point. Yet it was written by your keyboard player, Max Middleton.

“Actually, I hate that tune! It’s pretty awful. I could care less if people still like it. It felt like a slowed-done Irish reel to me.”

Was it your idea to record the Beatles’ She’s a Woman?

“No. Max Middleton was playing in a band for Linda Lewis. She was the wife of Jim Cregan, who is Rod Stewart’s guitar player. And she started making waves, playing Ronnie Scott’s jazz club. And Max said, ‘She does this song, She’s a Woman and people go crazy.’ They loved her version. And I turned it into a reggae, and that really seemed to make it take off.”

That’s one of the best-known tunes where you employ the mouth bag. How did you get into using that?

“There was a guy called Mike Pinera [guitarist for Iron Butterfly, among other acts] who had one, and he used to do just bass-riff noise and guitar lines with it. It took me about three or four days to get some of the vowel sounds out.

“Amplified through a mic, it gives you even more flexibility, because the mic reads certain frequencies more accurately. It would just floor people. They’d go, ‘What the hell’s that?’ Then they’d see this sort of colostomy bag stuck to me. In fact, there was a [concert] review where the [writer] thought it was a bladder.”

Did the mouth bag become a burden in the same way that Freeway Jam did?

“Yeah. Years ago, I checked into a hotel and the radio had been left on in the room. And I heard the bag being used, and it was Frampton Comes Alive! they were playing. [Frampton reportedly used a Heil Talk Box on the recording].

“I thought, Wait a minute, someone’s bootlegged my album, ’cause no one else was using that thing at that time. But it was Peter Frampton. And that was the abrupt end to my use of the bag. From that night on, I never used it.”

Beck boycotts the '80s

Released in 1980, There and Back provided a neat transition into a new decade for Beck – a bridge between his past and future. Jan Hammer was involved in three of the tracks, but the remaining four were done with keyboardist Tony Hymas, who would become a frequent Beck collaborator.

The '80s, however, were not one of Beck’s favorite decades.

“For most of the '80s, the business just went to a place where I didn’t want to go,” he said. “The clothes were more important than the music at one point, I think. The video prerequisite is something I wasn’t interested in, and the domination of synthesizers in the '80s made me very depressed – to think that they could possibly overshadow real playing. They did for a while, but lo and behold, real playing came back.”

Beck’s reputation was so solidly cemented by the '80s that he could afford to retreat to his English country acreage. The legend said that he’d rather work on his cars anyway. But it’s not like he became a hermit. In the company of fellow British rock royalty like Clapton, Page and the Stones, Beck surfaced for high-visibility charity events like the Prince’s Trust and ARMS.

As much as I still dearly love rockabilly, I don’t think that there’s much to be gained by pursuing that any further

He also laid down his wrenches long to play guitar on Mick Jagger’s solo albums, She’s the Boss and Primitive Cool, and to tour with Stevie Ray Vaughan and Carlos Santana.

Beck also received long-overdue recognition in the '80s. He won a Grammy for Emotions, a single off his 1985 Flash album, a synth-driven R&B effort produced by Chic guitarist Nile Rodgers. Grammy honors were also bestowed for 1989’s Jeff Beck’s Guitar Shop with Terry Bozo and Tony Hymas.

“And in 1993, perhaps as a way of regrouping after the '80s had safely passed, Beck went back to his earliest roots. Working with London rockabilly purists the Big Town Playboys, Beck recorded Crazy Legs, an album that paid tribute to Beck’s boyhood rock heroes Gene Vincent and the Blue Caps.”

On the Crazy Legs album, was it hard to stop being Jeff Beck and become Cliff Gallup?

“Are you kidding? First of all, I was heartbroken to learn that Cliff Gallup, Chet Atkins and all those guys in the '50s used fingerpicks. That’s the only way to get that crispness and clarity of tone. So I had to learn to play with those fingerpicks, and it was ghastly. They kept falling off and springing across the room.

“I thought at one stage I was getting quite close to it, but when I listen to the originals, tonally I’m nowhere near it.

“The stuff we did does have the spirit and sometimes the notation is perfect, but you put that old Gene Vincent and the Blue Caps album on and it’s just one of the major miracles of our time. As much as I still dearly love rockabilly, I don’t think that there’s much to be gained by pursuing that any further.

“One can’t progress by going back too far. I still use some of the gimmickry. Slap echo is always going to be one of the best inventions ever, but there the similarity ends, really.”

1999–2003: Beck goes techno

Beck celebrated the dawn of the 21st century in grand style, releasing Who Else! in 1999. The album was the first in a techno trilogy from Beck that also included 2000’s You Had It Coming and 2003’s Jeff. All three discs found the guitar master diving headfirst into the programmed beats and digital cut-and-paste disruption of contemporary electronica.

The albums teamed Beck with cutting-edge producers like Andy Wright, Apollo 440, David Torn (Splattercell) and Dean Garcia (Curve), but he also kept more traditional players like Tony Hymas and drummer Steve Barney in the fold.

Who Else! also marked the beginning of Beck’s collaboration with guitar virtuoso Jennifer Batten. The presence of talented women musicians in Beck’s bands continues today with youthful bassist Tal Wilkenfeld.

As the new century got underway, it was clear that Beck had no intention of joining the dinosaur fraternity of '60s and '70s rock stars whose best work is long behind them.

In a 2002 series of career retrospective concerts at London’s Festival Hall, Beck performed with everyone from veterans like Roger Waters and John McLaughlin to feisty then-newcomers like the White Stripes. Beck’s openness to new sounds and new ideas continues to keep him at the forefront.

Your playing achieved a new level of abstraction in the beginning of Trouble Man from Jeff.

“Oh dear!”

It’s like a Jackson Pollock canvas.

“The white coats were waiting to take me away.”

Was that just improvised off the cuff?

“Yeah. I think we wanted to have fun with no boundaries, with a drum loop and a real drummer. So there was a percussive [electronic] pulse going on, but real drums were there too, and we just let it rip for about 10 minutes.

“Then we found out it was too long to be hogging that much space on an album. So we edited it, and it lost a lot of the frightening immediacy that the original jam had. Maybe some day I’ll release the unedited version. It’s really crazy. A bit wild. Like Mothers of Invention wild.”

When you’re in the studio playing all this amazing stuff on guitar, are you totally blasé about it? Or do you surprise yourself as much as you surprise the rest of us?

“The thing is, I don’t surprise myself enough. Which is why on the song My Thing, for example, half of the solo was done live in the studio with about 30 people in the control room, falling over drunk. I like to go berserk, but with other people around. Because they actually do make me play slightly more energetically and frantically.”

Was there a main amp you used for Jeff?

“In the early stages I was using a [Line 6] Pod in a writing studio. There’s quite a lot of demo guitar left in there on the song Plan B. But most of the rest of the album was done with a [Marshall] JCM2000, and a Line 6 as well. It has quite a lot of variations that you couldn’t get out of the Marshall. The Marshall is great. But it has just that one characteristic.”

Which of your Strats are you playing on the album?

“‘Anoushka,’ she’s called. Because Anoushka Shankar [sitar virtuoso and daughter of Indian music patriarch Ravi Shankar] signed it for me. She’s divine. I said to her, ‘Just please sign this.’ And she did. She couldn’t believe I asked her. So now that guitar is Anoushka.

On the song Pork-U-Pine it’s amazing how you use the Strat’s vibrato arm to emulate the vibrato trills in Middle Eastern vocals.

“Well, yeah, one more element that helps me play is the way they sing, especially the Eastern Indian girls, when they do that amazing scale. It’s almost unwritable. You can’t even tell what’s going on unless you slow it down.

“And it’s great – a bit of oxygen for my playing style. I don’t like to rip off complete phrases, but some of the quick vibratos I do help me to form my own style, so I adapt it to the blues. Indian blues is really the way I describe it.”

With no bass player, drummer or keyboard player, it was just a natural progression, a natural thing you’d want to do – to go to a programmer and mess around with that

Regarding the very high pitched melody sections in the song Bulgarian, are you playing those with harmonics and using a wang bar to shape the melody?

“Yep. That’s how I do it. It’s not easy. Especially when the harmonic isn’t in the right notes. You know, when it’s a semitone sharp [i.e., from a natural, open string harmonic]. So rather than tune the guitar down, I’ll just bend the string down before I hit the harmonic and just guess at it. Or I’ll hit it and bend it up. Whatever it takes. There are no rules in that.”

But the techno phase of your career is now over?

“Yeah, it is. When you got Vinnie [Colaiuta] on drums, you don’t need that.”

But it was a great period. Really enjoyable.

“Yeah, but the thing that was missing was there should have been a great song, which there wasn’t. But those were fun tracks to do. They were just little sketches. I thought maybe they would be used in dance clubs or something.

“With no bass player, drummer or keyboard player, it was just a natural progression, a natural thing you’d want to do – to go to a programmer and mess around with that.”

Looking forward

In April 2008, Beck went into a California recording studio with Colaiuta and Wilkenfeld to record tracks for what became Jeff Beck's 10th album, Emotion & Commotion. “We jammed for about 10 days,” he said, “It’ll be a brave person who sifts through all that material, but I think we’ve got some interesting stuff there.”

So what is it that’s leading you back to the power-trio format?

“It was really just those particular sessions. I wanted to get away, go to California, get a bit of sunshine and work as well. And my keyboard player, Jason, was working somewhere else.

“So I decided to go in and see what I could come up with without any chordal support, without any of that direction, because keyboards tend to determine a direction almost immediately. You hear a chord and you’ve got one foot in a certain direction.

“But Jimi Hendrix didn’t have a keyboard player, for the most part. And with Vinnie on drums, you don’t really need much else going on. And with Tal as well, it was just a joy to blast away.

“We’ve got 17 hours of material on a hard drive, all sounding really good. I’m going to go through it all as soon as I get my head back together. I’m pretty spaced after touring all across Australia and then to New Zealand and Japan. So I’m coming down quite slowly.”

In a career that spans five decades, Alan di Perna has written for pretty much every magazine in the world with the word “guitar” in its title, as well as other prestigious outlets such as Rolling Stone, Billboard, Creem, Player, Classic Rock, Musician, Future Music, Keyboard, grammy.com and reverb.com. He is author of Guitar Masters: Intimate Portraits, Green Day: The Ultimate Unauthorized History and co-author of Play It Loud: An Epic History of the Sound Style and Revolution of the Electric Guitar. The latter became the inspiration for the Metropolitan Museum of Art/Rock and Roll Hall of Fame exhibition “Play It Loud: Instruments of Rock and Roll.” As a professional guitarist/keyboardist/multi-instrumentalist, Alan has worked with recording artists Brianna Lea Pruett, Fawn Wood, Brenda McMorrow, Sat Kartar and Shox Lumania.