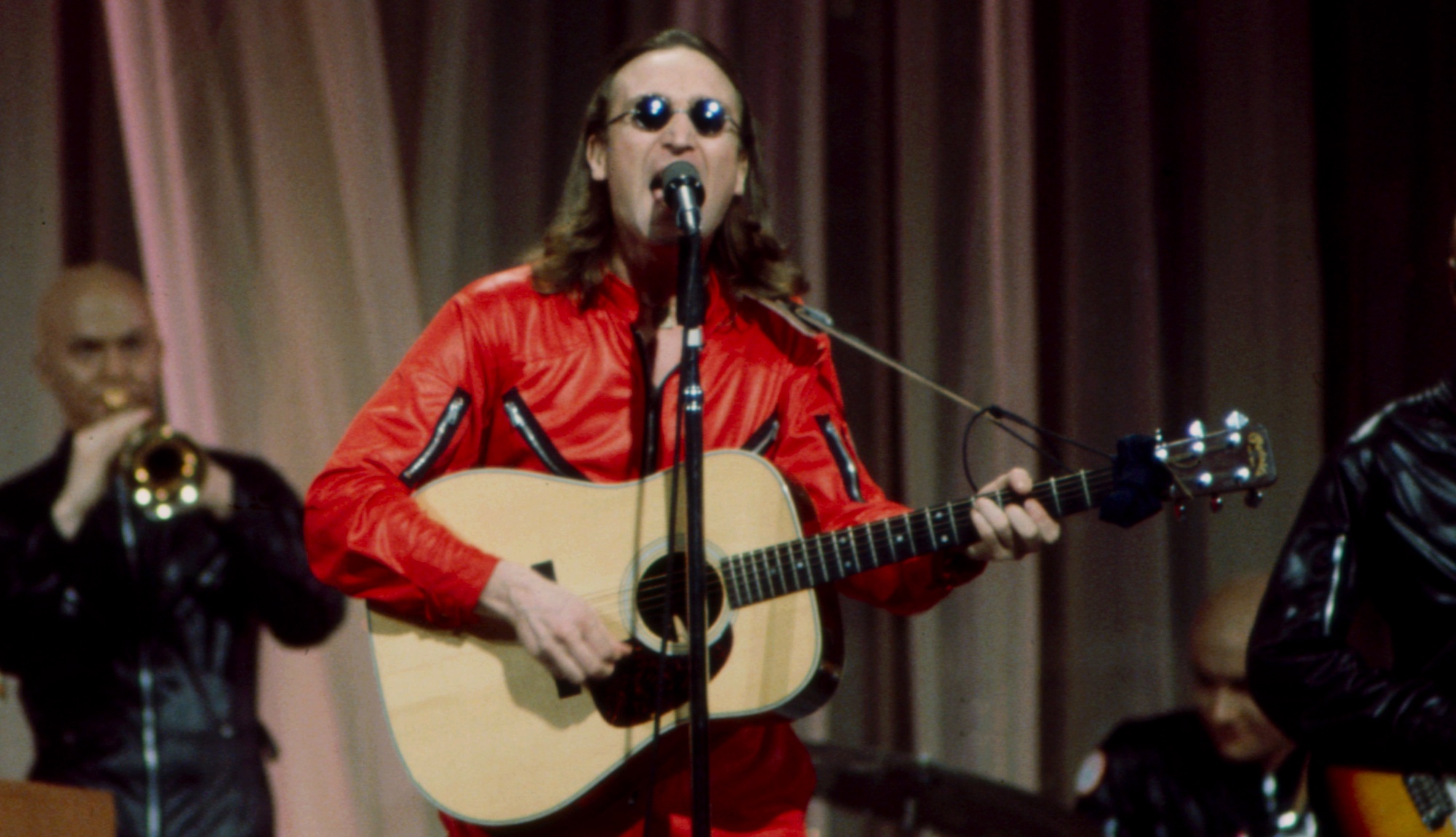

Joe Satriani: “It’s important to really identify with the subject matter”

18 solo albums down, Joe Satriani’s mind-bending musicality continues to evolve. On The Elephants Of Mars, he reaches new heights of narrative intensity

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Few musos have mastered the art of instrumental rock as dextrously as Joe Satriani. Satriani’s instrumental records are largely driven by poetry; he uses a broad palette of tones to paint spacious and vastly populated soundscapes, each serving to frame a story told through a language based on musical passages. A grisly, overdriven solo can portray a sense of doom, for example, each thundering note representing an actual jolt of thunder.

On the track ‘Faceless’, for example, Satriani explores themes of loneliness – “when the person you want to see you for who you really are doesn’t seem to recognise you” – where its cathartic solo “represents one’s true self finally breaking free”. It’s track three on Satriani’s 18th solo album, The Elephants Of Mars, which the Westbury, New York-native shredder said could be considered the “new standard” by which instrumental albums should be judged. It comes from his intention to establish “a new platform of [Satriani’s] own design”.

Australian Guitar cornered Satch to chat more about his ambitious vision for The Elephants Of Mars.

18 albums in, how do you keep it all feeling fresh and exciting? Are there still barriers you want to break and goals you want to kick?

All the barriers I want to break are my own. I’m still a struggling guitarist. It’s still hard to play guitar – I still have to slow down every day and go, “What is wrong with this finger? Has it forgotten its purpose in life!?” I’ve never felt like I’m as physically gifted as some of my really good buddies, so I work extra hard for that sort of dexterity. But the writing is what I love the most – and that really depends on my ability to be truthful and honest with myself. It’s really hard to just bare your soul to whatever recording medium you’re working with, and then share it with people. It takes a weird kind of discipline, and you can’t let up. You have to make it your way life. You really have to decide, “I’m going to do this, so I better get used to it.”

It’s like when a priest takes that oath, right? You’re dedicating yourself to the culture and the craft.

It’s true! When I was just a teenager, I remember taking lessons from Lennie Tristano, and he was trying to get me to understand that to be a musician meant living a very serious life. He used to say things like, “There are no vacations for musicians.” You never think in the subjunctive – you never think you should have, you could have, you would have – you just be. You learn everything there is to learn, you don’t kid yourself, and then when you play, you give no judgement. They were basically Zen lessons, and they were impossible to master. But you take them on as life quests, I suppose. And at the end of the night, it’s still rock ’n’ roll, and I still want to have fun onstage with my guitar – so it’s all filtered through who I am, and what I like to do, and how I like to share my music with people.

How do you tell a story with just your guitar and that tonal landscape?

It’s important to really identify with the subject matter, and to make a decision that you’re going to recognise and eliminate any techniques that don’t belong, or that aren’t going to support a unique story for a particular song. I think for rock guitar players, there’s always that danger that your audience may mistake a certain part for a solo because it’s got too many notes in it. And that’s our own fault, y’know, because we like to play!

The electric guitar is always seen as occupying that space in the band – when you want things to go crazy, you let the guitar player go crazy, y’know? He’s not the guy in the band that you depend on to explain the song. So as an instrumentalist, I have to reorient my tools to make sure that when I’m playing a melody, I’m always putting it in the simplest terms. I play as few notes as possible, and I have to edit and edit and edit, and then figure out a way to listen back and go, “Okay, I’m a normal person listening to this – does this part have too many notes?”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Especially having recorded all of these new songs remotely, how much did they evolve over time?

This record has so many different versions of me accomplishing the track. Somebody else asked me about my method, and I went, “I don’t have a method!” I always just go with what’s working, you know? Like, the last song on the album, ‘Desolation’ – that was a little two-minute piece that Eric [Caudieux, engineer] really wanted to expand and make into a full song. But when he finally sent it to me, it was 22 minutes long – it had this long introduction, then my piece in the middle, then this three-minute improv of an orchestra. And I listened to it for months before I realised we needed to get rid of the first part, get rid of the second part – even though I wrote it – and just keep that last part. Because it was saying something to me – I just didn’t know what it was.

But that’s so entirely different from the first song on the record, ‘Sahara’, where I came into the studio with a feeling and a person in my mind, and a particular set of lyrics, and it all came at once, and I recorded that whole song in a few hours. The only real big misstep with that was that I wrote the lyrics for Ray to sing, and then somehow that never got done so we turned it into an instrumental.

As far as the recording goes, this was the first time you did everything using plugins, wasn’t it?

Yeah – a plugin, actually! I usually record DI anyway, just so we can reamp the sessions later, and I’ve done that for over 20 years – we take the DI track off the session, we use John Cuniberti’s reamp, and we send it back out into the Marshalls, the Peaveys and the Fenders, and it always works great. But this time around, we had all those tracks side by side, we would A-B them, and it was always like, “Wow, what’s that one? Oh, it’s the SansAmp! That can’t be right, did you mislabel that? That’s gotta be the Marshall…” But as it turned out, down to the very last song, the only amp I used was the SansAmp plugin, that old AVID plugin from the ‘90s.

It just didn’t interfere with or homogenise me. And that’s the thing: it always sounded more like me than any other version we got from all the great modelling suites they’ve got out there, or from reamping with the Boss Waza amp or the reamp device. I couldn’t understand it myself, I was really shocked. The first thing I did was call the guys at IK Multimedia and say, “Sorry!” But they were cool with it, because y’know, when they approached me about doing the AmpliTube 5 suite, it was to celebrate my old sounds. So they went, “Well, that’s okay – that [suite] celebrates your older tones, and we love it, and people love it, so we’re going to keep selling it, and you can still be associated with it, even though you’re playing this old plugin.”

So when you play these songs live, are you going through a digital rig?

No, I’ll use my Marshall JVM410HJS – that thing sounds amazing. It’s got so many tones in it. The important thing is how it reacts to my guitar’s volume control – y’know, I can take a sound that you think might be a germanium distortion box, put it through a loud Marshall, pop up my high-pass filter and tweak the volume knob just a little bit, and suddenly you go, “Wow, it sounds like an AC30!” It’s amazing how [the JVM410HJS] reacts to simple guitar controls. That’s what I’ve always loved about it. You’ve got to get it up pretty loud, though – once it gets to be around 112 decibels, it’s really something beautiful.

Ellie Robinson is an Australian writer, editor and dog enthusiast with a keen ear for pop-rock and a keen tongue for actual Pop Rocks. Her bylines include music rag staples like NME, BLUNT, Mixdown and, of course, Australian Guitar (where she also serves as Editor-at-Large), but also less expected fare like TV Soap and Snowboarding Australia. Her go-to guitar is a Fender Player Tele, which, controversially, she only picked up after she'd joined the team at Australian Guitar. Before then, Ellie was a keyboardist – thankfully, the AG crew helped her see the light…

- Ellie RobinsonEditor-at-Large, Australian Guitar Magazine