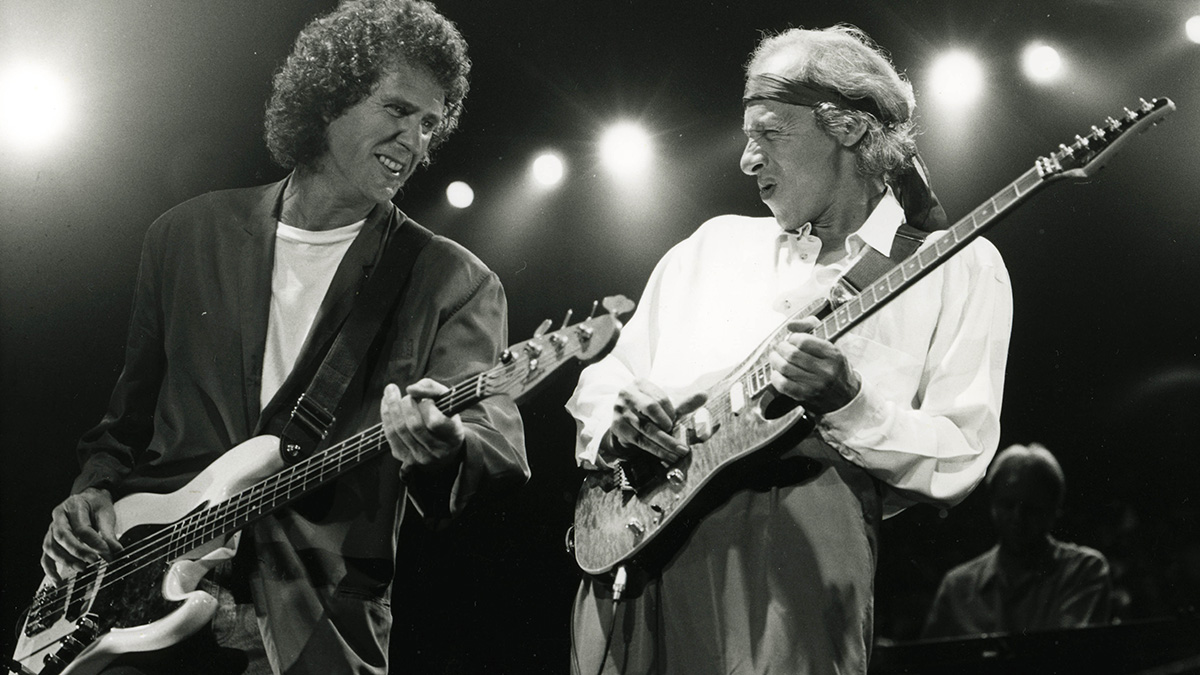

John Illsley reflects on Dire Straits' stadium-rocking success, the pressure it put on Mark Knopfler, and tells us what makes a great bass part

The bass player conquered the world with Dire Straits, and as he reflects on his time in a new memoir and a new solo album, he can say they survived: “We stayed intact, and stayed friends”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

120 million albums on this planet bear the bass parts of John Illsley, who recently released his memoir, My Life In Dire Straits.

The autobiography traces his journey from the earliest days through the ‘80s, when the Straits were an unstoppable, ubiquitous force – and beyond them, too. From the outset of the project, he tells us, he wanted to ensure his memories were contexted accurately.

“This is not about me scoring points,” says the bassist. “It is a celebration of the time we had and how we survived it. We stayed intact, and stayed friends – and a lot of people don’t. I decided right from the word go that I didn’t want people coming at me saying, ‘No, I didn’t say that – how dare you!’”

Article continues belowHe adds: “I know some people will find glaring problems with my book, because their version of events is different from mine. This is my version of events. A lot of people did get hurt on the way, for various reasons, and you don’t want to get them to revisit that. I don’t think it’s fair.”

Aside from My Life and its associated audiobook, fans wanting a little more information can always nip down to the East End Arms, a pub and hotel that Illsley bought in 1990 in order to secure it for the local community. Situated in the New Forest National Park, the venue is renowned for its good food and great atmosphere.

“It’s basically a local boozer where you can get a good meal,” he says. “There’s also a public bar where the locals go in, and it’s like a mini community center, I think. It’s nice when people tell me they had to come to the pub [because of John’s musical background], and people are a bit more respectful now than they probably used to be.”

You won’t see Illsley changing barrels or pulling pints, though. “I don’t do that,” he confirms. “I just take care of the feel of the place, like I take care of the feel of the music.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

That feel is crucial to the work he’s produced over the years. Although Illsley has bass chops to spare, he’s never been one to dominate a song with twiddly flashiness. “Like John McVie, I like to leave as much space as possible, because the essence of bass – as far as I’m concerned – is to make the rhythm section, the engine room, as tight as possible, particularly in Dire Straits.”

He continues: “That was my approach from the word go, to leave room for keyboards or guitars. I could have put in a whole load of other notes, but in a sense, leaving air around the bass had something quite significant to do with the Straits sound – certainly on the first two albums.”

That pair of late-‘70s releases – 1978’s self-titled debut and ’79’s Communique – put the group front and center of the music scene. They were a band in the purest sense, too, with everyone pitching in to get the bandleader Mark Knopfler’s songs to sound the best they could.

The pinnacle of the Straits career was the remarkable Brothers In Arms, released in 1985 and soaring to number one in multiple territories. That LP alone has sold 30 million units – another unfathomable number. Dire Straits certainly put the hard work in to make that record shine, recalls Illsley, of the Caribbean-tracked release.

“There was a lot of preparation done before we actually went to the studio. We explored lots of different ideas, so that when we got to Montserrat there wasn’t a lot of messing around. We knew pretty much how we were going to put it down.”

As he explains, “Our band was really about feel, pretty much from the word go. The thing that I enjoyed, probably more than anything else, was trying to get that feel right. You know, sometimes you hit a string a bit harder than you would normally, or you hold back on it, or let it ring longer or shorter. You have to feel your way into the song.”

I started on bass in 1964 or ’65 and I thought, ‘Yeah, I feel comfortable in this space... This is me’. I felt at home pretty much straight away

There is a purity to approaching music in such a way, and for Illsley it was key in him picking up the bass guitar in the first place. “I started on bass in 1964 or ’65 and I thought, ‘Yeah, I feel comfortable in this space’. The space was the bass and I thought, ‘This is me’. I felt at home pretty much straight away, and then it was, ‘Okay, what can I do with this music?’”

As well as the aforementioned McVie, particularly on the early records, Illsley nods to a couple of the bassists that he admired at the time.

“I thought Bill Wyman was perfect with the Stones, and Paul McCartney is always recognized as a fantastic songwriter. Some of his basslines are extraordinary. As for Jaco Pastorius, just watching him on one occasion was mind-boggling. It was at the Rainbow Theatre in London.

“He did a half-hour solo just on his own and I thought, ‘Well, I don’t know what’s going on here. I’ve no clue. But whatever you’re doing is just off the scale, off the planet’... I wouldn’t dream of playing like that because that’s not me. I am fascinated by how different people approach the bass.”

Like many people in their earliest musical endeavors, Illsley was in a covers band. “We wanted to be the Animals, so we did Don’t Let Me Be Misunderstood and lots of Chuck Berry stuff,” he recalls. “I was just copying what was going on around in those days. Rock ’n’ roll and blues is my area – I’m very much in the tradition of songwriters, and I have to admit most jazz doesn’t do it for me.”

We did 30 days without a break, without a day off. I turned to somebody in the dressing room and said, ‘Does anybody have any idea where we are?’

Illsley has a refreshing attitude towards bass equipment; he has never had an endorsement, he says. “I did get approached by a couple of people over the years but I said, ‘Thank you. but no.’ I could endorse new Fender basses, which are absolutely fine and I’d use one live if I didn’t have a budget.

“On occasions we’ve had a truck break down so we used new gear, but if I’m standing there with a ’61 Jazz... you can’t endorse old gear like that. I’ve obviously collected a few guitars over the years, because you just do without trying very hard. I look after them and keep them, but with amplifiers I don’t need much these days. They just clutter up the studio.”

Back in the Brothers In Arms days, Dire Straits were running a monstrous rig, with a bunch of solid-state Ampeg SVTs, although by the time 1991’s On Every Street came around, Trace Elliot had constructed a bespoke backline for Illsley.

“Pretty much everything was hidden,” he says. “It was clean, with graphic equalizers and goodness knows what going on. I gave all that to some school a few years ago. I thought, somebody else should be using this – I don’t need it any longer.’”

The only piece of bass gear he’s ever missed is a black Wal which he thinks he ‘might have lent to somebody.’ He still has a red fretless version to hand, but these days, his weapon of choice is a vintage Jazz.

Post-Street, Dire Straits was coming toward a natural end: years of touring take their toll.

“Everybody thinks it’s just a whole load of fun,” he says. “Look, there’s an awful lot of fun elements to being in a band, no doubt about it. But if you can imagine, there was a moment on the On Every Street tour when we did 30 days without a break, without a day off. I turned to somebody in the dressing room and said, ‘Does anybody have any idea where we are?’ and they said, ‘Just check the itinerary’..

“You get into this mode of activity with the music, the travel and the venues and you think, ‘Is this Germany or Austria now? Or Switzerland?’ It sounds ridiculous, but you’re in this sort of bubble that travels around, isolated from reality.”

After being in the eye of the hurricane for nearly 15 years, the band – individually and collectively – wanted to explore different avenues.

Mark Knopfler took a lot of energy from the outside world, being the writer and all the rest of it, so he got a massive amount of attention – and after a while I guess he just didn’t want to handle the machine any more

“Mark Knopfler took a lot of energy from the outside world, being the writer and all the rest of it, so he got a massive amount of attention – and after a while I guess he just didn’t want to handle the machine any more.

“We were playing to ridiculous-sized audiences, with all that equipment, and in order to keep it rolling it became like an army on maneuvers. I’m quite a calm person most of the time, so hopefully I kept everybody from going off and misbehaving too much.”

Misbehavior, certainly in the ’80s rock sense, often meant musicians stuffing their careers up their noses. Not so for Dire Straits, and certainly not so for Illsley, who was more enamored of another Colombian export.

“You might as well have a couple of pots of coffee and save 20 quid or whatever,” he chuckles. “To be honest, I’d rather open a nice bottle of wine and have something nice to eat after the show. When you finish work, it’s 11pm, and it takes you two or three hours to wind down.

“If you wind yourself up again with narcotics, you get into a terrible cycle of self-destruction as far as I can see. It’s difficult for some people, because sometimes they think, ‘I’m so tired, I need some help to get on stage’, but the fact of the matter is that as soon as you walk on that stage you get an incredible lift from everybody that’s there.”

Next up for Illsley is VIII, his eighth solo album. Live work is also on the table, though it’s less all-consuming these days, and comes with some very modern issues.

Occasionally, people remember bass parts – but it’s more about the theme of the music and the sound of the music. Can you feel the bass?

“We did a festival in Germany which had been kicked down the road three times because of COVID,” he says. “The only way we could do it with the Brexit regulations was literally get on the plane with a guitar each, fly to the gig and fly back again.”

As ever, he has strident thoughts about the role of bass. “It’s a bit like George Harrison’s guitar in the Beatles,” he explains. “Almost every lead guitarist says George was the one who stands apart, because you always remember his lead part. Occasionally, people remember bass parts – but it’s more about the theme of the music and the sound of the music. Can you feel the bass?”

“Right now I’m just doing things that I enjoy doing. If something comes into my world that speaks to me, I’ll do it. Like a one-off gig in space!”

Another mind-bogglingly big idea: you can bet that if the numbers made sense, he’d be on the first rocket up there. We’d put 120 million on it if we were you.

- My Life In Dire Straits and VIII are out now via Penguin and 100% Records respectively.