“If I overplayed behind a singer, there’d be a fight outside the venue, or a guy waiting for me with a knife!” Marcus Miller on why bands need to offer a “little more love and support for vocalists”

Always in demand, Marcus Miller looks back on his 2008 solo effort, Marcus

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

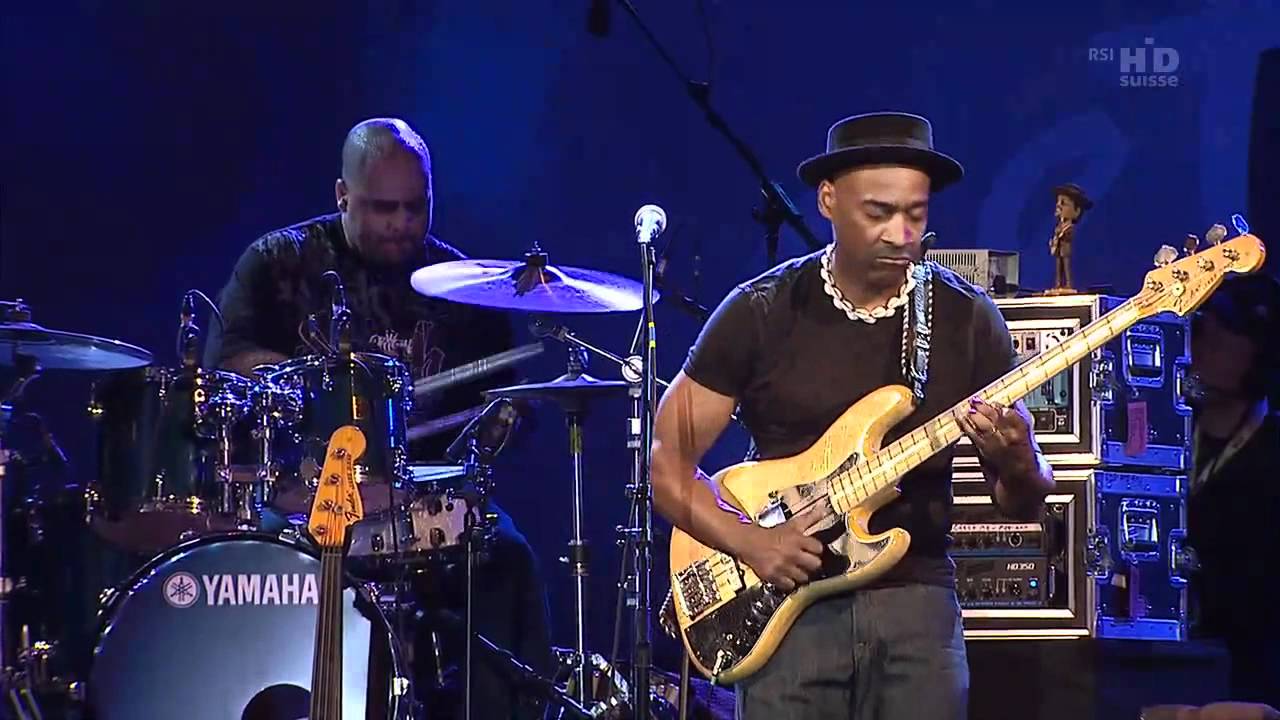

Bassist extraordinaire, saxophonist, producer, composer, session musician and one-man phenomenon Marcus Miller will require little introduction for most. He first came to prominence as a member of Miles Davis's band in 1981, remaining with the jazz icon for the next eight years.

Countless sessions as a sideman, film composing, and another dozen years of enhancing his master-of-all-trades, music-mogul status finally led to his 1992 solo debut, The Sun Don't Lie.

In the years since, the multi-Grammy-winning Miller has displayed the prism-like qualities of all great jazz musicians, absorbing the popular music and culture of his time and reflecting it back through his own inimitable voice.

“When I started, with The Sun Don't Lie, I was determined to focus on my bass playing and composition in the same contemporary jazz vein I'd been doing with Miles,” Miller told Bass Player. “But with each successive album, I've tried to open it up and show a bit more of myself.”

His 2008 solo effort, Marcus, was a reminder that while we're on a first-name basis with the sound and many of the musical moves that emanate from Marcus Miller's bass guitars, the methods are not always as clear, and that adds an additional element of fretboard fascination.

Back in 2008, Miller paused to offer insight into the musical world he inhabits and the making of his seventh solo album, Marcus.

Marcus seems to have a greater range than any of your previous solo albums.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

"The title refers to people knowing my name but having different ideas of who I am; this disc shows all of my musical sides. Although the trend in pop music is to have multiple singles in different formats, I still believe in the concept I grew up with, in which an album is a whole statement – almost like a concert. I felt like my sound on bass and the way I put the music together provides a through-line that holds all the songs together.”

What inspired the Middle Eastern sound of the opening track, Blast, and what was your harmonic guideline?

“I've been hearing people experimenting with that tonality – Timbaland uses it a lot in hip-hop, on tunes like Beyonce's Baby Boy. I thought I could give it another dimension, with jazz.

“While we were on tour in Istanbul, I bought this clarinet. When I put my mouthpiece on it and played a major scale, this weird Turkish scale came out! I put it back in the case until I could shed on it, but it did get me to write Blast.”

“For the track, I tuned the E string on my '77 Jazz down to D, and I basically went back and forth between two scales: either D, Eb, F#, G, A, Bb, C, D, or the same scale with a major 7th (C#), to get a nice minor 3rd in the middle, Bb to C#.”

Funk Joint and Strum sound like throwbacks to your original template: bass features with starkly contrasting bridge sections.

“Strum came from a bassline I found moving around intervals of major and minor 6ths in the middle of the neck. I liked it so much I played it throughout the track, except for grabbing the bridge melody.

“Funk Joint was funny because I'd moved away from the Miles/muted horn sound I was known for, and I had Patches Stewart and Gregoire Maret play the countermelody. Well, what does open trumpet and harmonica sound like together? Muted horn!

“The bridge is basically III-VI-II-V with different substitute chords and a simple diatonic melody that holds it together on top. That's what a lot of the gospel cats are doing now; they're playing all those traditional diatonic church melodies, which they can't mess with, so they move around the harmonies underneath.”

Gospel music and church-trained musicians are everywhere these days.

“Gospel is a great breeding ground because it's one of the only places where musicians can open up without worrying about commercial format restrictions. As a result, new styles have emerged that folks are embracing, personified by artists like Tye Tribbett and Israel & New Breed, whose Christmas album I got to play bass clarinet on.

“The only thing I'd like to see from some of the gospel bands at times is a little more love and support for the vocalists. When I was coming up, if I overplayed behind a singer, I'd get my ass kicked. There'd be a fight outside the venue, or a guy waiting for me with a knife!”

Your covers of Stevie Wonder's Higher Ground and Miles Davis's Jean Pierre seem live-band-focused.

“Higher Ground and also When I Fall in Love were the result of having a tour before we started the album and wanting to play some new material; we pretty much called them on the spot, and they developed so well along the way, I decided to record them.

“Jean Pierre is a tune that I've been wanting to revisit, but I waited because everyone else was doing it after Miles passed. The melody and harmony are so simple you have to work to find depth in the tune. That's what I like about it.”

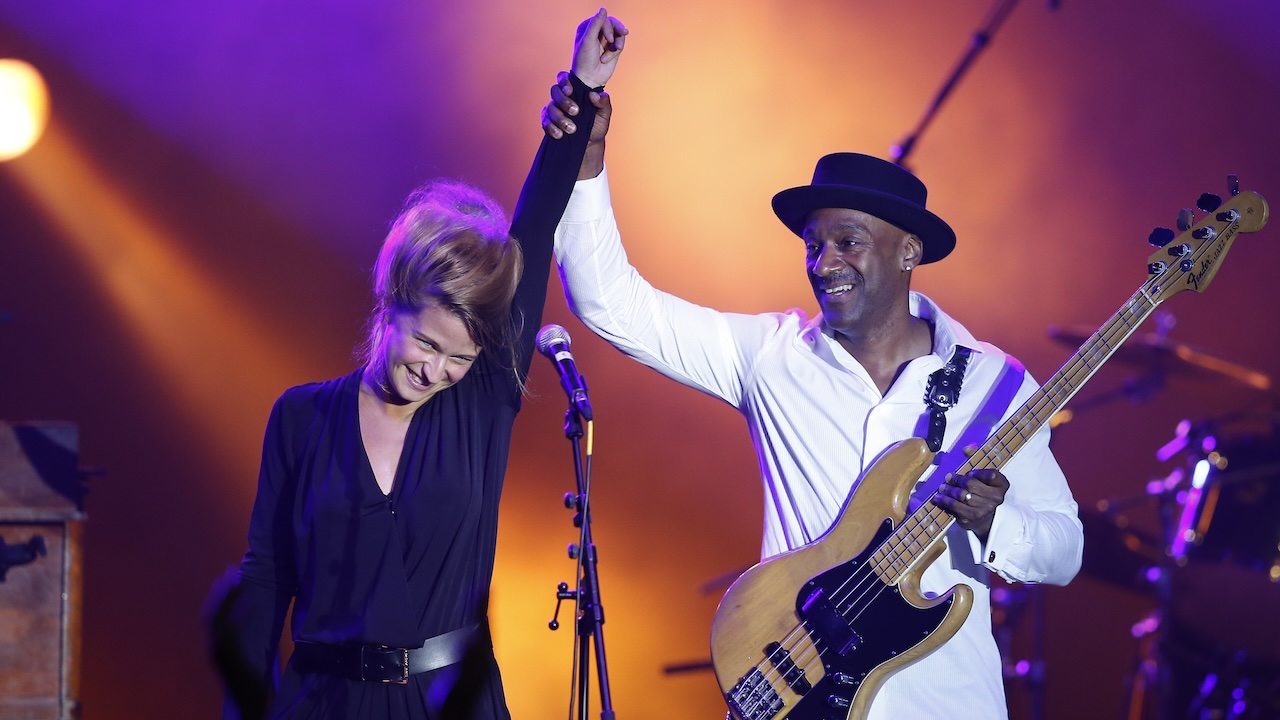

How did you arrive at Corinne Bailey Rae singing a cover of Deniece Williams' Free?

“I was in my car and I heard Corinne singing her hit, Put Your Records On, and I just loved her voice; it was so different and distinctive. I pulled over and began the process of tracking her down, to see if she'd be interested in appearing on the album. It turned out she was a fan of our music and was glad to be asked.

“As soon as I hung up from her, Free came into my head. I called her back to see if she knew it, and she said as a matter of fact she was just listening to it the week before. I put on two bass tracks: a hold-it-down track on my Jazz 5 and a lead track on my '77 Jazz.

“Funnily enough, I was familiar with Verdine White's playing on the Deniece Williams version, but I didn't know Nate Watts co-wrote the song until I saw him at the NAMM show and he said, ‘Thanks for doing my tune!’”

Another current pop link is your cover of Robin Thicke’s Lost Without U.

“When I heard it, it sounded like a Brazilian tune to me. The song's producers probably don't know much about Jobim – they just came up with this new sound in the hip-hop realm, and because it was new to them, it sort of provides a fresh take on a samba feel, which is what drew me to it.

“I wanted to give the melody a different focus, so I have the female vocals and I weave in and out with the melody on my '77 Jazz; plus there's a track of me playing the guitar-like chordal figure on my Fender 5, with a C string on top.”

Your reprise of Lost Without U, as well as Cause I Want You, ventures into spoken word.

“I’d done a spoken-word track with Meshell Ndegeocello in 1994, so when someone asked me about doing spoken word and recommended Taraji P. Henson from the movie Hustle & Flow, I thought it was a good idea. No one has been combining music and spoken word in a forceful, funky way.

“For Cause I Want You, we sent the track to various poets as a contest, and Shihan the Poet, from HBO's Def Poetry Jam, was the best of the bunch. We got him together with Taraji, and they really delivered on their respective tracks. And of course, Lalah Hathaway does her vocal and lyrics thing on Ooh, which was a song I'd done for a Japanese best-of disc and always wanted to revive.”

Your bassline is front-and-center on Cause I Want You, but it still plays a repetitive role. Have you found that to be mandatory in spoken word?

“I think so, because if you do any kind of improvising or stepping out, it turns into something else. That kind of music relies on a simple, steady sort of tribal hypnosis from the bottom. But if you think about it, that was the case on plenty of old R&B and funk songs, from James Brown right through the '80s.

“When I first learned the bass part to Papa Was a Rollin' Stone, the hardest thing for me was not putting anything between the notes. There were a bunch of other basslines in that same vein, like Cymande's Bra, Mandrill's Fencewalk, and Larry Graham on Thank You (Falettinme Be Mice Elf Agin).”

Sonically, your bass has a different sound on Cause I Want You, while the whole album features your trademark array of low-end bass, keyboard, and kick-drum colors. Do you have a regular starting point on the bottom?

“It's been the drums, through the hip-hop side of my music, but I've been starting to fool around with bass at the bottom. You're hearing that more with the return of the old school, vintage-bass-and-flatwounds sound. The challenge is to convince the engineer, because they're so locked into starting from the bass drum – but bass at the bottom can really open up the music.”

“Ironically, Cause I Want You started from the drums. I was on the kit, playing a groove I wanted to record – but we had only one overhead mic in the room and didn't get a strong bass drum sound. So it was the perfect song to let the bass do the carrying. I backed off the neck pickup slightly on my '77 Jazz, and I thought about Bernard Edwards; I always liked the way you could really hear his notes on those Chic-produced dance tracks.”

The interlude track, Pluck, is another upfront bass groove.

“That came about from finding a new way to play with my thumb and index finger, which is hard to describe. Instead of striking the string with my thumb and coming off, and popping with the index finger and coming off, I'm reaching under the strings with my thumb and index finger and plucking, but I'm keeping my hand on the strings, so I can get right back to the notes.

“When I came up with the bassline, I noticed the technique made the accents come out in interesting places. What I was going for was an atmospheric interlude that was all about the groove, no soloing. I also wanted a reference to the opener, Blast, so l grabbed the sitar I used on that track and played a background melody using the same kind of Middle Eastern D scale.”

What led you to cover What Is Hip?

“I've been playing that song as a warmup since it came out, and eventually I arrived at the same place I did with Teentown: oh, man, this sounds completely different when you play it with the thumb. That was the genesis.

“There was certainly no point in playing it with fingers after Rocco Prestia's definitive part. So I used up and down thumbstrokes, à la Larry Graham or Victor Wooten – striking through the string and coming back up with the thumbnail. It's not a big forearm swing; it's pretty controlled.

“We did the song at a faster tempo, which makes it easier to play and maintain command of the bass line. Pumping it like Rocco at the original tempo would have been much more difficult.”

The addition of Chester Thompson on organ provides a key Tower Of Power connection.

“I thought it would be cool to fly up to Oakland to see if Chester would do it; he was down, and it was a great hang. It's always fascinating when you meet someone who played on a classic record, because you hear things that didn't make it through the original mix – in his case, chords I didn't know were there.”

“Its interesting how those guys played off the E dominant 9 tonality; they're really dancing around in B minor, moving the D-F#-B shape that works so well chromatically from above or below.

“It also helped that Chester has been playing the song in a trio setting for a long time. That was my concept: using a quartet, with David Sanborn and Poogie Bell, to try to create the T.O.P. sound and energy. I saw Rocco and Emilio Castillo in Mexico a few months ago, and they thanked me for doing the song.”

What are you most proud of, professionally speaking?

“Oh, man, I'm just proud of having a career. I've seen so many other people who've had substantial careers, and I've seen the whole arc of their career from beginning to end - and I'm still here. When I started out, man, they were doing the original soul and jazz, and I've been around long enough to see the resurgence of that music. I've seen techno, I've seen neo-soul, all that stuff. I'm just really grateful to be around, and to see how music is evolving.”

Chris Jisi was Contributing Editor, Senior Contributing Editor, and Editor In Chief on Bass Player 1989-2018. He is the author of Brave New Bass, a compilation of interviews with bass players like Marcus Miller, Flea, Will Lee, Tony Levin, Jeff Berlin, Les Claypool and more, and The Fretless Bass, with insight from over 25 masters including Tony Levin, Marcus Miller, Gary Willis, Richard Bona, Jimmy Haslip, and Percy Jones.