Metallica, Megadeth and Def Leppard guitar techs discuss survival on the road and life 20 feet away from stardom

"When the show is over and the gear is packed up in the truck, it’s satisfying to see 75,000 people leave with smiles on their faces"

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

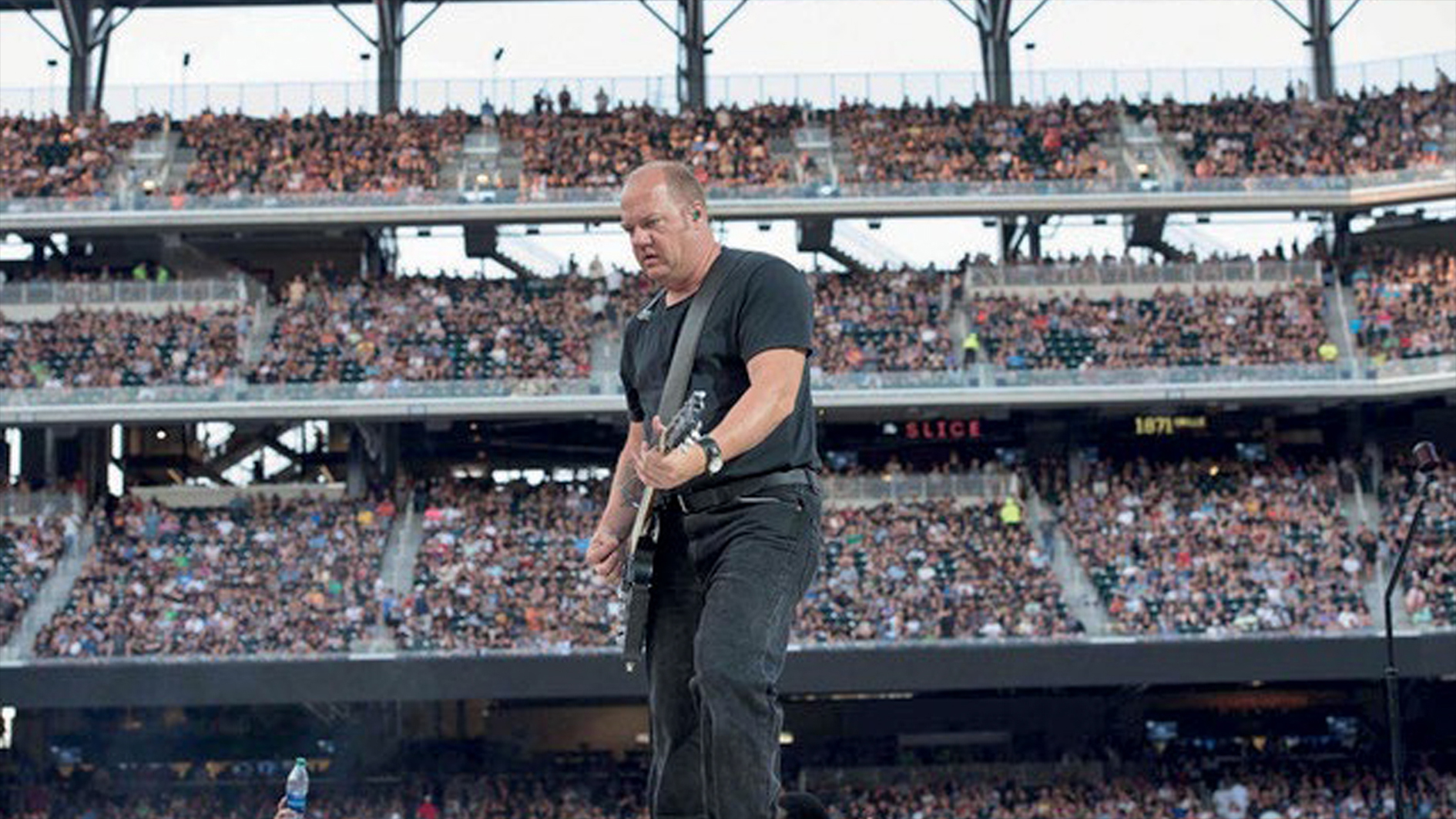

Metallica’s members performed more than enough hijinks and shenanigans to earn their reputation for alcohol-fuelled hedonism. For the past 16 years, Chad Zaemisch has been along for that ride - just don’t count on him for too many debauched stories from the road.

While James Hetfield is playing the opening riffs to Nothing Else Matters or Master of Puppets to thousands of adoring fans, Zaemisch is the guy who made sure the guitar was set up, restrung and in tune, that the ever-evolving amp and effects rig was in order, that the wireless system isn’t pulling a Nigel Tufnel and that the metal god is, in general, a happy deity.

Zaemisch is one of the all-too-often anonymous guitar techs, a profession that is done best when nobody in a gigantic audience realizes he exists. Going by stereotypes perpetuated by pop-culture oddities like 1980 comedy Roadie (a forgotten film whose unbelievable cast includes Meat Loaf, Alice Cooper, Roy Orbison and Blondie) or the Tenacious D song of the same name, life running the backline is a cycle of shlepping amps and then partying till you puke.

The reality, according to Zaemisch, is far more mundane. On Metallica’s recent summer tour, his day started at 9 a.m. to load in and didn’t stop until well after tens of thousands of fans had filtered out of the venue.

“By that time, it can be 11:30 or 12 at night. It can be a little hard to wind down after all that excitement and work and that level of energy,” he says. “Next thing you know it, it’s 2 a.m. and you’re thinking about having to get up at 7:30 so you’d better try and get some sleep.”

As with rock stars, it’s a long way to the top if you want to rock and roll. But for guitar techs, it’s also a path marked by insane hours, lots of manual labor and constant, tedious re-stringing. It’s not for everybody, but helpers to some of rock’s biggest names told Guitar World the truth about life 20 feet away from stardom.

For somebody whose life revolves around guitars and guitar accessories, it comes as a surprise that Zaemisch started off as a drummer. While his mom taught him a few guitar chords, he focused on the skins, playing in bands through high school and eventually drifting through a few jazz classes.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

A course in sound engineering led to a revelation - a life was possible that combined the creative and technical aspects of creating music. Drawn by the energy of live performances, he started working live sound.

I wanted to tour, I wanted to get out and see the country and whatever else I could see

Chad Zaemisch

“I wanted to tour, I wanted to get out and see the country and whatever else I could see,” he says. “That was sort of my path to doing that.”

During a stint with one company around 1993, he met a fellow roadie gearing up to work on an upcoming Lollapalooza tour. They passed along word that '90s alternative rockers the Breeders were looking for a guitar tech. Zaemisch once ran the band’s monitors, so the gig seemed like the perfect fit.

The festival turned out to be a perfect networking opportunity. On the road, he met people working for the Breeders’ management. Another of their clients, Hole, were looking for a guitar tech and they turned to Zaemisch.

“You tour, you meet people and work with people, you can find other bands through management companies or friends or people you know,” he says. “That’s how you get a lot of the not-so-serious people weeded out as you start working for bigger and bigger bands.”

The connections soon paid off in a big way. While Zaemisch was on tour with Garbage, Kirk Hammett’s longtime tech Justin Crew came aboard as a fill-in drum tech. The pair hit it off.

“We got along famously - we had a good time working together and had a lot of laughs,” Zaemisch says. “It was a few years later where I saw Justin, I think I was filling in for him with Tori Amos. He said, ‘James let his guitar tech go last night.’ I said, ‘Well, put my name in the hat,’ and he did.”

Zaemisch ended up being shortlisted and was soon flown out to California to meet with Hetfield. “He asked me about who I was and what I had done and what my philosophies were. It was the first job interview I’d been on in probably 20 years or something. It was a little nerve wracking. They called me half an hour later and said, ‘You’re hired; James likes you.’”

Zaemisch’s band-hopping experience isn’t unique. While he’s now exclusively on the Metallica payroll, other techs jump from tour to tour, looking to keep the income coming in when the band they’ve been working for takes a break or is in the studio. Take Willie Gee, a self-described “jaded, grouchy, boring roadie” whose career has been anything but boring.

Over the course of several decades, “if a band plays guitars and has long hair, I’ve either worked for them or toured with them,” he says, adding with a laugh, “I also worked with Black Eyed Peas.”

if a band plays guitars and has long hair, I’ve either worked for them or toured with them

Willie Gee

Most famously, he spent years teching for Megadeth’s Dave Mustaine but also did time with Anthrax and Slayer. As we speak, he’s prepping for a Whitesnake tour, though he’s run into some slight roadblocks. He’s having a headache of a time dealing with a late shipment of a pickguard. This comes after another snafu involving late picks. “Things like this tend to happen. I’m just cursed,” he jokes.

Despite, or possibly because of, his history of misfortune, Willie Gee has learned some pretty valuable lessons about how to survive on the road, especially with a boss as notoriously prickly as Mustaine. Rule one: Understand who your boss is so you can anticipate their needs.

“People say, ‘How did you work for Megadeth for so long?’ I say, ‘You guys never met my family. I’ve been around crazy a long time.’ I can deal with a lot of different or extreme personalities because I’ve been around it my entire life,” he explains. “But I also happened to be a Megadeth fan. By the time I started working for them I was really well versed in his entire catalog.”

David Bernson, who has worked for everyone from Jewel to Paramore to Adele to the Offspring, sees himself partially as a therapist whose ultimate task is keeping their artists’ head in the game: “As a guitar tech, no matter who you’re working for, one of the most important things is to be able to give them the confidence they need to be comfortable on stage and put on a performance in front of 20 to 100,000 people,” he says.

“As that person’s tech, you’re the first person between that person and the rest of the world. If they’re having an issue with anything, someone in the audience, a personal issue, you’re the only one that directly communicates with them. Being able to keep them happy and in the state of mind they need to be in is more important than the actual music being played.”

Aside from amateur psychologist, there are a wide array of technical skills needed. Gee was well equipped to take on his first tour in the mid-'90s, having spent years tinkering with guitars and pedals at home; he was recruited by a buddy for that first tour partially because of his skill with a soldering iron. Staying up to date on the latest tech can be a challenge by itself.

Gee says that while he’s still hoping to master more of his job by attending a luthier school, he’s picked up a lot of knowledge by watching peers while they work. He recalls watching a tech for Slipknot rebuild a blown-out amp head using spare parts and having the rig ready to go by showtime, with nobody the wiser about the brush with catastrophe.

“I’ve got an insane amount of guitars. The amount of gear I have makes some people nervous,” he says. “I’d work on my own things mostly out of curiosity or not being able to afford to get someone who’s more qualified to do it. By trial and error, you figure some things out. I ask a lot of questions and read a lot of magazines.”

You have to figure out what they need as an artist and how to accomplish what they need to do in the show

Scott Appleton

Having spent a few years with Journey’s Neil Schon before joining up with Alex Lifeson of Rush, techie Scott Appleton now finds himself helping out Def Leppard. Learning the intricacies of new rigs is part of the challenge that keeps the job fulfilling. “That’s the challenge - you have to get inside another guitar player’s head,” he says.

“There are obviously basic things every guitar player needs, but you still have to figure out what they need as an artist and how to accomplish what they need to do in the show.”

Those minutiae can take some time to learn - while some players are ready to rock as long as they have an instrument in their hand, others can be picky about how each guitar is set up, what kind of tubes they have in their heads, how a pedalboard is organized.

“There’s a lot of what they like as a setup on their instruments. Are you heavy handed or a light touch? Do you like the action high or action low?” Appleton says. “Then you get into small things like where do you want picks on stage or what kind of beverage do you want?”

Good techs also need to be able to multitask. Once a band is on stage, a tech could find him- or herself replacing a broken string or retuning a guitar for the next song while still needing to focus on the current song as they handle their boss’ patching and effects switching. Bernson says just learning the material well enough to be an offstage part of the performance can be a challenge.

“It’s different with each band. When I walked into Trans-Siberian Orchestra, they didn’t tell me I had to do that, so I had no preparation at all. I had to learn the songs and I wrote charts for myself of where I needed to hit distortion,” he says. “I learned songs while I was rehearsing. I messed up a few times before the show but by the time the show was there, I nailed it.”

With gigs coming and going at a rapid pace, some guitar techs find themselves becoming generalists, equally able to help out a bassist or drummer. Aside from the guitarists he’s worked for, Bernson has also been the long-running bass tech to No Doubt’s Tony Kanal. But while he’s gained a lot of technical knowledge, he says the skill that’s most important to longevity in the job is simple, yet elusive for some people: knowing how to not be a jerk.

“You’re living on a tour bus with 12 guys. You’re in a different city or country every day, dealing with the technical side of things live. In outdoor venues you can be freezing cold one day or rainy and hot the next day, and maintaining instruments with those weather changes is a challenge,” he says.

“When you’re on a tour, you’re in a bubble. You see the same people every day and you get to know people very quickly. A lot of my friends, even if I only toured with them for a year, it feels like you’ve known them for 10 years.”

I’ve seen a few guys over the years that think they can play better than the guy in the band, which has nothing to do with anything.

Chad Zaemisch

Being nice enough to not openly spit in your bus-mates’ faces is one thing. It’s another thing to remember your role - something that can be difficult for some when they’re so close to the spotlight. Because of the nature of the job, techs tend to be musicians themselves.

Gee spent time in wedding bands before hitting the road, while both Appleton and Bernson were touring musicians before turning to the tech life. People who can’t put aside their own dreams of stardom can fizzle out in a hurry.

“I’ve seen guitar techs who are frustrated musicians, and it is not a good place to be,” Zaemisch says. “I’ve seen a few guys over the years that think they can play better than the guy in the band, which has nothing to do with anything.”

For guitar nuts who think they can get along in that kind of selfless position, a career as a tech might sound appealing. But just as a wannabe musician can find themselves puzzled about how to get their career started, it also can be overwhelming to consider how you go from adjusting intonation at home to getting paid to do the same thing for Hetfield.

Zaemisch says aspiring techs should come ready to work, and that means being properly equipped. When you’ve figured out a likely band that needs a tech, go work for them and be prepared - be the guy with the extra set of strings, a spare 9-volt battery and some reasonable expectations of what awaits you.

“I’ve seen a lot of people start at the local level and know people who are in the bands you like in your area,” he says. “Go try and work for them and try and see who’s up and coming and going places. Try and get involved with them at the starter position, which might include setting up all the gear by yourself and driving the van and selling merch. If that’s what you want to do, you gotta pay your dues.”

The one thing a tech knows at the start of every tour is that there’s an end date. Eventually, everybody has to go home. While it could be easy to get sick of guitars after months focusing solely on the technical aspects of the instrument, some techs still find joy in sitting down with a six-string once they’re off the bus.

Bernson gigs with a rockabilly band when he’s off the road and Gee says he still gets joy from messing around with his gear. Zaemisch rebuilds old motorcycles and cars to relax, but he tries to spend as much time as possible with his family. The very nature of the job makes maintaining family ties incredibly difficult; Bernson says he never thought he’d get engaged - until he met his fiancee, a wardrobe coordinator, while working on an Adele tour.

“It weighs more heavily on some people than others,” Gee says. “I can’t jam with any friends, I can’t be in a band because nobody wants the guy who’s never around in the band. I can’t have a dog. There’s certain things you take for granted.”

When the show is over and everything went well and the gear is packed up in the truck, it’s satisfying to see 75,000 people leave with smiles on their faces

Chad Zaemisch

It’s not an easy path - as Gee says half-jokingly when asked for advice for those looking to follow in his footsteps, “Other than looking for something else, you mean?!” It’s an often thankless role, where your boss gets all the glory and you’re left to do whatever it is that needs to be done to keep them happy.

“You’re the technician, sometimes you’re the bartender, you’re the psychiatrist, you’re the babysitter, you’re the bodyguard. I call myself the finder of impossible objects,” Gee says.

But even after decades of endless restringing, carrying heavy amps and a zillion bus rides, Zaemisch says it’s still worth it to be part of something great.

“There are some people that have larger egos that are fueled by being with the band. When the show is over and everything went well and the gear is packed up in the truck, it’s satisfying to see 75,000 people leave with smiles on their faces,” he says. “You’re part of the whole experience. If you’re a fan of music in general, it’s really satisfying. Besides, I couldn’t handle an office job.”

Adam is a freelance writer whose work has appeared, aside from Guitar World, in Rolling Stone, Playboy, Esquire and VICE. He spent many years in bands you've never heard of before deciding to leave behind the financial uncertainty of rock'n roll for the lucrative life of journalism. He still finds time to recreate his dreams of stardom in his pop-punk tribute band, Finding Emo.