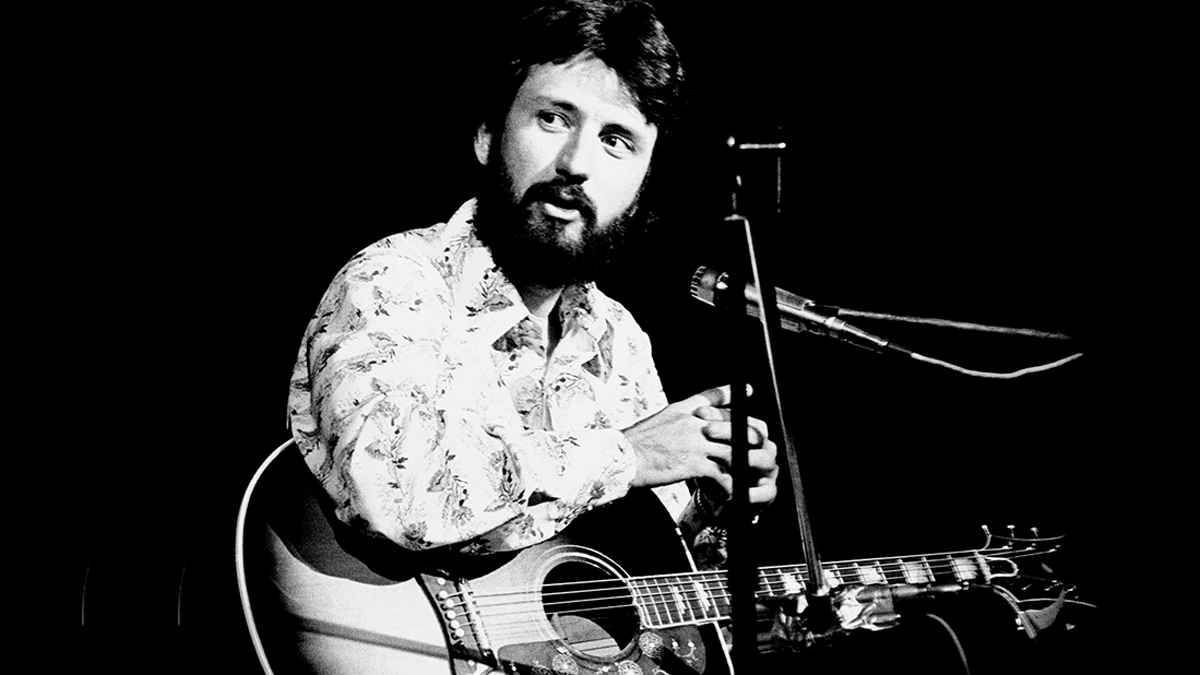

Remembering Michael Nesmith (1942-2021)

A trailblazer for pop culture, film producer and alt-rock inspiration, the former Monkee was a polymath whose career was guided by his gift for songwriting

A man of many talents and broadband, multimedia vision, Michael Nesmith is a uniquely difficult artist to categorize. “Nez,” who died of heart failure at age 78 on December 10 at his home in Carmel, California, experienced major mid-to-late Sixties fame as a member of the Monkees – the made-for-TV rock group that morphed into a real band over the course of its initial four-year career.

He spent much of the rest of his life trying to come out from under the Monkees’ shadow, and come to terms with the quartet’s unlikely legacy. His indelible association with the Monkees tended to obscure his solo career as a country-flavored songwriter, guitarist, singer and record producer, not to mention his enormous contribution to the birth of pop music video and the MTV era.

Of the four young men chosen in 1965 by television producers Bob Rafelson and Bert Schneider to become Monkees, Nesmith was the most musically seasoned. The tall, drawling Texan had been kicking around L.A. since ’62, playing the clubs and hosting “Hootenanny Night” at the Troubadour.

He’d released a few singles on small labels. As a songwriter, he’d inked a publishing deal that would see his tunes recorded by artists like the Paul Butterfield Blues Band, Linda Ronstadt and the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band, among others.

On the strength of all this, Nesmith was able to cut a deal with the Monkees’ music supervisor, Don Kirshner, whereby Nez would be the only Monkee allowed to sing and produce two of his own compositions per Monkees album – but not play any of the instruments.

The group’s other three members – Peter Tork, Micky Dolenz and Davy Jones – were only allowed to sing. Nesmith, by contrast, landed himself in the producer’s seat, directing a roomful of L.A.’s finest session players – guitar legends like James Burton, Glen Campbell, Carol Kaye and other members of the legendary Wrecking Crew. Nesmith always seemed to have had the big picture in mind. But he had a clear-eyed vision of his strengths and weaknesses as a songwriter.

“My primary craft is writing,” he told Guitar World’s Damian Fanelli in 2013, “and songwriting was always what moved me along. I fell into the folk scene early on because of the importance of the song and lyrics there, and then followed that with some rock and roll and country efforts.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“When I got on the show, the pop community was strange to me and, by and large, didn’t respond well to my songwriting or singing. The show didn’t do anything to help that. I was always outside the main effort of the show’s music. I would’ve liked to have been more accepted as a pop song writer, but there was little I could do about it since I didn’t know how to write a pop song.”

I would’ve liked to have been more accepted as a pop song writer, but there was little I could do about it since I didn’t know how to write a pop song

Nesmith’s song Mary, Mary nonetheless became a sizable hit for the Monkees in 1967. But for most of his time with the group he “traveled to the beat of a different drum” – to quote the ’67 hit he wrote for Ronstadt.

But when the Monkees seized control of their own music on their third album, 1967’s Headquarters, Nesmith played a bellwether role, recording and producing more of his own compositions with the group, and coming into his own as a guitarist. He played the model 6075 and 6076 12-string electric archtops that Gretsch had made for him, as well as the occasional steel guitar part.

The Monkees TV show was enormously popular. Many aspiring garage band guitarists identified with Nesmith’s playfully intelligent demeanor, sardonic wit and even the stupid wool hat the show’s producers required him to wear, after he’d turned up for his audition with the thing on his head. But the Monkees were also derided for not playing their own instruments.

The Monkees’ obvious indebtedness to the Beatles got them labeled “The PreFab Four.” Their lighthearted televised hijinks hit a sour note at a time when rock was starting to take itself more seriously.

The actual Fab Four, however, were pro-Monkees. Nesmith was at a dinner party with John Lennon, Paul McCartney and Eric Clapton when someone played a tape by a then-unknown artist called Jimi Hendrix. The Monkees hired Hendrix to open for them on tour in 1967. But Hendrix was a little too loud, wild, weird and maybe even a little too Black for many among the Monkees’ pre-teen audience. He left the tour after only seven dates.

The Monkees nonetheless trickled into the counterculture to a certain degree. Their psychedelicized 1968 feature film Head featured a cameo by Frank Zappa and was sufficiently trippy and well-made to attract admirers. A man with his own eye on the visual media, Zappa was pro-Monkees as well.

But not everyone in his audience – nor Beatles fans for that matter – shared his vision. In his 2017 autobiography, Infinite Tuesday, Nesmith offered a clear-eyed take on the Monkees backlash phenomenon:

“If the 17-to-20-year-old Beatle fan and serious music lover loathed the Monkees as a cheap copy, the 9-to-12-year-old television baby thought they were a matter of fact. Their television set was coming to life… Older brothers and sisters might shout them down, but the preteens had their own reality, even if they couldn’t explain it.”

The twain never did quite meet, and the counterculture current became the wave of the future. NBC-TV, however, wasn’t quite ready to dive into that wave. The Monkees’ show was cancelled in 1968. The hits stopped coming. Tork jumped ship in ’68. Nesmith soldiered on for one last album, 1969’s The Monkees Present, and left shortly thereafter, in 1970.

He started the new decade with a new career phase, forming the First National Band in 1970, with pedal steel ace Red Rhodes. Their wistful recording of Nesmith’s sentimental ballad Joanne, charted at Number 21 on Billboard’s Top 100.

The First National Band were early participants in the groundswell of country-inflected rock that had been touched off by the Byrds’ landmark 1968 album Sweetheart of the Rodeo. In a sense, the First National Band is one of the missing links in the chain that leads from Sweetheart to the Eagles’ mega-platinum self-titled 1972 album.

Over the course of the next three decades, Nesmith would release a dozen albums of country-flavored rock – as a solo artist, fronting the First National band or its successor, the Second National Band. He made his mark as a producer as well, with albums by U.K. folk guitar legends Bert Jansch and Iain Matthews.

Simultaneously, Nesmith emerged as a founding father of the MTV era. The pioneering video clip that he made for his 1977 song Rio was key to the launch of PopClips, a music video program that predates and was a probable inspiration for MTV, which launched in 1981.

The Rio clip became part of Nesmith’s groundbreaking longform video Elephant Parts, which won the first-ever Music Video Grammy – a brand-new category that debuted in 1982. All this was produced under the aegis of Nesmith’s Pacific Arts Corporation.

From his perspective as a co-star of one of the ’60s’ most successful pop music-related TV programs, Nesmith had seen the future from a perspective few others had at that time.

“When the [Monkees] TV show came online, there was a hidden element that nobody really understood, of television making its way into the culture,” Nesmith told journalist Paul Wilner in 2017. “But nobody really understood what was going on, except perhaps Marshall McLuhan [who famously coined the phrase, ‘the medium is the message.’] I only see now, in retrospect, how television was creating its own reality.”

The “TV babies” who’d loved the Monkees in their pre-teen years were now coming of age, and video would become an integral part of their pop music experience – something that holds true to this very day. And Nesmith was in on the ground floor. He produced videos for Michael Jackson and Lionel Ritchie during this period, and also began producing feature films, including the 1984 cult classic Repo Man.

For a while Nesmith held himself aloof from Monkees reunions. This was often read as a sign of his disinterest, or even contempt. But it may well be that he was just plain too busy with his many multimedia projects. He began to warm up to his old bandmates in the latter half of the ’80s, doing one-off concert and TV appearances, and eventually embarking on full length tours with the group.

He was fully onboard for the 1996 album Justus, which was entirely written, performed and produced by all four Monkees. Nesmith reprised one of his best-loved songs, Circle Sky from Head and also took a lead role in the album’s production, finishing mixing while the other three went out on tour.

Half a decade down the road, the zeitgeist had shifted considerably. The Monkees had become cult heroes for a generation of alternative rockers

He wouldn’t make another record with his former bandmates until 2016’s Good Times!, the Monkees’ 50th anniversary album. Half a decade down the road, the zeitgeist had shifted considerably. The Monkees had become cult heroes for a generation of alternative rockers.

Adam Schlesinger from ’90s power-pop icons Fountains of Wayne produced Good Times! and played bass on many of the tracks. Songs for the album were contributed by a post-punk Who’s Who that included Andy Partridge (XTC), Rivers Cuomo (Weezer), Ben Gibbard (Death Cab for Cutie), Noel Gallagher (Oasis) and Paul Weller (the Jam/Style Council).

So Mike Nesmith spent his final years basking in the glow of this much-belated hipster recognition. Following the deaths of Jones and Tork, Nesmith continued to tour with Dolenz, while continuing to create his own music. His final album, Rays, appeared in 2005.

But in 2018, he was forced to cancel the last four dates of a tour with Dolenz, and needed to undergo quadruple bypass heart surgery. He returned to action in 2019 and played his final date with Dolenz – the concluding night of the Monkees Farewell Tour on November 14, 2021, at the Greek Theater in L.A. Less than a month later, he was dead.

“He was really comfortable in the end,” Nesmith’s manager Andrew Sandoval told Variety. “He told me in his living room just a few months ago, before the tour; he said, ‘You know, I finally really have come to accept the Monkees’ music. I really like it now.’ He started to see it more through the eyes of his fans, of how they loved it. And that was bringing him a lot of joy at the end of his life. Their joy was coming back on him. He finally really felt that, and it lit him up, you know?”

In a career that spans five decades, Alan di Perna has written for pretty much every magazine in the world with the word “guitar” in its title, as well as other prestigious outlets such as Rolling Stone, Billboard, Creem, Player, Classic Rock, Musician, Future Music, Keyboard, grammy.com and reverb.com. He is author of Guitar Masters: Intimate Portraits, Green Day: The Ultimate Unauthorized History and co-author of Play It Loud: An Epic History of the Sound Style and Revolution of the Electric Guitar. The latter became the inspiration for the Metropolitan Museum of Art/Rock and Roll Hall of Fame exhibition “Play It Loud: Instruments of Rock and Roll.” As a professional guitarist/keyboardist/multi-instrumentalist, Alan has worked with recording artists Brianna Lea Pruett, Fawn Wood, Brenda McMorrow, Sat Kartar and Shox Lumania.

![B.B. King [left] cups his hands to his ear as he asks the crowd for more. Joe Bonamassa, with a Les Paul, gives his crowd a thumbs up](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/P3XrQLh86C27JfPp4AGp6n.jpg)