All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Do yourself a favor and pick up Mo Foster & Friends In Concert, which its creator hails as “some of the very best musicianship that I’ve ever captured on one of my own recordings”.

On the eve of release of the album, Mo takes time out to reflect with BP on his diverse portfolio, kicking off with a snapshot of life in Swinging London.

“In the mid-'60s, you have to understand that there was jazz and then there was rock. They were two separate genres of music that had nothing to do with one another – at that time, there was no crossover.

“It wasn’t until a couple of albums by Miles Davis and Blood, Sweat & Tears that the artistic lines began to blur. Davis bought in electric piano and electric bass, which nobody had ever heard, let alone contemplated before.”

How did Mo enter this fertile music world, we ask?

“At university we had a jazz trio. Linda [Hoyle, singer] was first introduced to us through our keyboard player, and we spent the summer of 1968 rehearsing. Our band Affinity was born, and we were immediately signed to a manager, Ronnie Scott. The project came as a result of attempting to delve into both rock and jazz camps, so essentially, we were playing jazz-rock for the first time”.

This was a truly seminal time to be an active musician in the capital.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“Indeed, we regularly played Ronnie Scott’s Jazz Club in London, and even found ourselves supporting the great Stan Getz’s quartet. I remember one afternoon seeing Jack DeJohnette practicing straight 16ths patterns prior to a show, and six months later he was delivering it on Bitches Brew with Miles. What I had unintentionally witnessed in real time was the start of the transition from jazz to fusion.”

He namechecks another key musical relationship:

“I’d met the guitarist Ray Russell in a Transit van traveling up the M1 four years prior to the recording of Ray’s 1977 album, Ready Or Not. It was stunning for me to be part of that recording, as it felt like an American record, with so many influences – horn and string sections, plus a great rhythm section featuring Simon Phillips.

“At the time you’d hear like-minded material coming out of American through the likes of Herbie Hancock and Chick Corea, but there was nothing like that here. To witness it coming out of Basing Street Studios in Notting Hill was novel.

“The composition Surrender, written with a friend of mine, Tim Whitehead, was the first tune I ever wrote! The opening riff, played on my Fender Jazz, was heavily influenced by Anthony Jackson’s on Money, Money, Money – and has since gone on to feature in a Ron Howard film.”

1979 was the beginning of a dense period of touring and recording for Foster, where a whole sea of artists began to grace his resumé. One of these was Gerry Rafferty and the album Night Owl.

“This was a pivotal time and recording for Gerry, who had all sorts of problems with management and musicians, so had fired half the band. Naturally, new faces came in, and I was one of those.

“Gerry would present a song on piano, then you’d have to figure out what the key was, what the chords were, what the structure was, write down your own chart and even write down the inversions, as his chords were very sophisticated. Of course, the choice of bass note ultimately alters the emotions which are portrayed in the music.”

Was this a laborious process?

“Not at all – the experience was very sociable! We spent two weeks in the Cotswolds at Chipping Norton Studios, where we lived together as a family and every evening was greeted with a barrel of Hook Norton beer. Routining sometimes consisted of up to 12 hours revising and refining a single song, and then we’d have the final version.”

Glancing through Foster’s awe-inspiring resumé, you can’t help but notice the presence of a number of innovative artists beginning to appear at the start of the '80s, notably Jeff Beck.

“In 1980 we recorded the There And Back album for Jeff. He had started the recording, but wasn’t happy with the line-up, so he brought in Simon Phillips and Tony Hymas, who had been in the Jack Bruce band before that.

“Stanley Clarke had left and I was one of a shortlist for the bass seat, which also consisted of John Paul Jones and Rick Laird, who had been working with John McLaughlin. I think it must have been all my jokes that got me the job!”

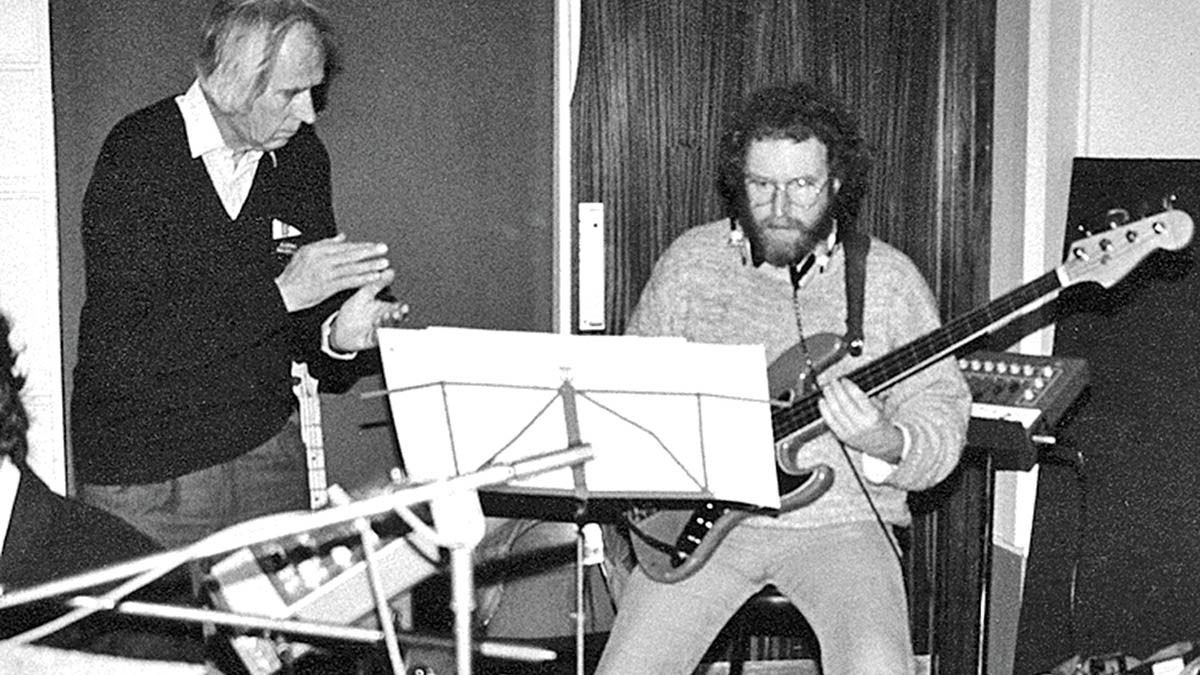

Space Boogie was a very hard song, a fast 7/8. I had to have the music sellotaped together across three music stands in the control room of Studio Two

How did everything transpire once he arrived at Abbey Road?

“A lot of the tracks were already recorded, so I had to overdub to keyboards and drums. Space Boogie was a very hard song, a fast 7/8. I had to have the music sellotaped together across three music stands in the control room of Studio Two.

“It would have been good to have been on casters, so somebody could have pushed me along while I was performing it... When I finished, Simon and everyone reached down below their seats and bought out score cards to mark my performance!”

Foster’s association with so many rock artists may come as a surprise.

“By the end of 1980 I was working with the Michael Schenker Group, which was being produced by Deep Purple’s Roger Glover. The rehearsals were in a very small room in Nomis Studios in Shepherd’s Bush, London.

“Schenker turned up with a full Marshall stack, while all I had was a Roland Cube, which was like a cornflakes packet in comparison! Thankfully, back in those days I used to smoke, so I took two Marlboro cigarettes out of the packet and put them in my ears, filter first. I looked ridiculous, but it worked!”

Michael Schenker turned up with a full Marshall stack, while all I had was a Roland Cube, which was like a cornflakes packet in comparison!

While working for producer Chris Neil, Foster was part of a British ensemble reminiscent of LA’s Wrecking Crew. One More Time is a forthcoming documentary, produced by Alan D. Boyd, attempting to honor this prestigious period.

“I was part of a house rhythm section which included Peter Van Hooke on drums and Phil Palmer on guitar. We’d play on everything of the day, including an album for the actor Dennis Waterman. A couple of years later, one of the tracks, I Could Be So Good For You, was picked up for a television series called Minder.

”This was the song which featured my aluminum-necked Kramer 650B, which I bought as you couldn’t get Alembics at the time. I had been listening to the likes of Louis Johnson, and was keen to adopt his slap approach for the Waterman session.

”The problem was I had never seen him play, so I had to invent a way. What you hear on the record is a combination of that instrument and me simply being spontaneous.”

The line-up of the Phil Collins band at this time was formidable – how did that gig come up?

“I got a call to go to the Townhouse Studios to overdub a couple of parts for the producer Hugh Padgham. Phil never tells you what he wants – you just listen to the track and play along, developing ideas until he says yes.

He’s a dream to play with, because he’s got such beautiful time. He drives and swings, but never speeds up – it’s amazing. After completing his album Hello, I Must Be Going, I remember Phil asking if I’d like to go on the road with him.

The subsequent live album, Live At Perkins Palace, was filmed, recorded and engineered by Robert Margouleff. Lee Sklar came up to me after the show to say how much he had enjoyed it, which was a lovely compliment as I think he was originally intended for the line-up, but was unavailable due to commitments with James Taylor.”

“Phil was always a total professional, just getting on with the job, working very hard and expecting you to do the same. During the first week of tour rehearsals we had just the basic rhythm section at Shepperton Studios – Chester Thompson, Daryl Stuermer, Peter Robinson, Phil, and me.

“I have this lovely memory of Phil standing at the mic with a book of lyrics, as he had no idea of what he’d written! During the second week, the Earth, Wind And Fire horn section turned up. They all thought I was Swedish, as that’s where we’d originally met while I was working with Frida Lyngstad from ABBA.”

I composed a fun announcement for Gary Moore, saying to the audience, ‘Would you please welcome a dear friend of ours, and one of the finest guitarists in his price bracket...’

Mo’s sessions with Gary Moore in 1983 supplied some surprisingly challenging moments, he says.

“As you can imagine, Gary was a big fan of Jeff Beck, so I think that was why he invite me to play on the Victims Of The Future album. I remember a nylon-strung guitar solo during Empty Rooms that he wanted me to copy on fretless. I had to sit down in the studio and learn it phrase by phrase, twice, and then I doubled it to achieve that wonderful Jaco sound.

“Gary was such a lovely guy. I remember doing a couple of charity shows where Ray Russell and Gary Husband and I had invited him to join us as a guest artist. I composed a fun announcement for him, saying to the audience, ‘Would you please welcome a dear friend of ours, and one of the finest guitarists in his price bracket...’”

Gil Evans is always held in high esteem, and when in 1983 an opportunity arose for Foster to tour with the seminal composer and arranger as part of the British Orchestra, he jumped at it.

“I was in America, on tour with Phil Collins at the time. I rang Ray, who was at home looking after my diary, and he said ‘When you get back you’re going on the road with Gil Evans’. My immediate response was “What? My hero?’

“It was a difficult show. Gil’s music was hard and never very clear. You had to listen to 10 people at once to figure out what you were supposed to play. Gil was very much a free spirit. I remember him standing in front of this established brass section, examining some incredibly complex parts together, and then very quietly he said, ‘This is the note I’ve written for you, but if you don’t like it, feel free to play another one’.

“They were different times, when you’d play with everyone. Cliff Richard was one of the good ones, but there was also a lot of gigs there just to pay the rent. I was invited to join Cliff’s band around 1977 or ’78 to tour Europe, Hong Kong and Australia, and that started a long affiliation.”

Somewhat nostalgically, he adds...

“Move It was the first ever piece of English rock ’n’ roll, recorded back in 1958. Jump forward and Cliff wanted to re-record the composition on the same spot in Abbey Road for his Two’s Company duets album, supported by Brian May, Brian Bennett of the Shadows and me.

“Brian turned up at the studio nearly an hour late, looking very tired, but with one of the best excuses I think you’ll ever hear! He said, ‘I’m sorry lads, I’ve been up all night with [the legendary astronomer] Patrick Moore, proof-reading a book that we’ve co-written on the history of the universe’. How do you even begin to top that?”

- Mo Foster & Friends In Concert is available now via Right Track.