The making of Pearl Jam's Ten: from the depths of despair to a bold and defiant debut

The full story behind the grunge-rock masterpiece

The letters, when they started coming, all began in the same way. “I was recently considering suicide,” they said, “and then I heard your music.” The letters were often about a song called Black, and they were always addressed to a band called Pearl Jam.

The catalyst for the letters was a performance the band had given on MTV Unplugged in May 1992. The Seattle quintet had released its debut, Ten, about half a year earlier, but the record had yet to grow into the stupendous hit it would become. At the end of the group’s rendition of Black, a quiet memorial to heartbreak, singer Eddie Vedder, intense with emotion, sang, “We belong together…together.” They were evidently words that hundreds of lonely teens needed to hear.

By the end of the summer, Ten had gone Gold and had reached No. 2 on the Billboard charts; it would eventually sell more than 11 million copies. The album would also help bring about the ascension of alternative music, while Vedder, along with Nirvana’s Kurt Cobain, would be viewed as the voice of Generation X.

But despite the fact that Ten is one of the best and most important albums to have emerged from the '90s, Pearl Jam have in recent years distanced themselves from it. Some of this disavowal may be due to the album’s metal slant; bassist Jeff Ament has previously told Spin that he’d “love to remix Ten,” if only to “pull some of the reverb off it.”

It may also be due to the disdain with which Ten was held by Cobain; a punk purist by then, the Nirvana singer insisted that an album with such prominent guitar leads couldn’t really be “alternative”. But perhaps some of this distancing also has to do with what a personal album Ten was – and the fact that once it was absorbed by the public consciousness, its meaning became distorted, and it no longer belonged to the band alone.

Pearl Jam had never meant for Ten to be a message to a disillusioned generation, a salve for their feelings of isolation. Instead, it was a cathartic purging of pain and loss. It was also, for two of the band’s members, something of a rebirth. Just one year before the album was released, they had watched a close friend die – and take their dreams of success with him. With Ten, they were given something very rarely granted: a second chance.

In 1990, the “alternative” music scene was nothing more than a scattering of musicians operating independently of each other. Guns N’ Roses were the biggest band going; hair metal was still the reigning sound.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

But in Seattle, a mini-scene was coming together, the culmination of almost a decade’s worth of bands working as a community, putting out their own records and performing around town for the hell of it.

These bands were actually starting to enjoy some sort of success as well: Soundgarden had just seen their album Ultramega OK get a Grammy nomination and were about to put out Louder than Love, their first release for the major label A&M. Nirvana’s debut, Bleach, had caused such a stir that Geffen had swooped in and signed the band away from local indie Sub Pop. And Sub Pop itself – a stronghold of Seattle talent – was enjoying attention on a worldwide scale, having launched an aggressive marketing campaign that included flying over a British music journalist to write up a spread on its bands for the U.K. music weekly Melody Maker. In effect, the Seattle hype was beginning.

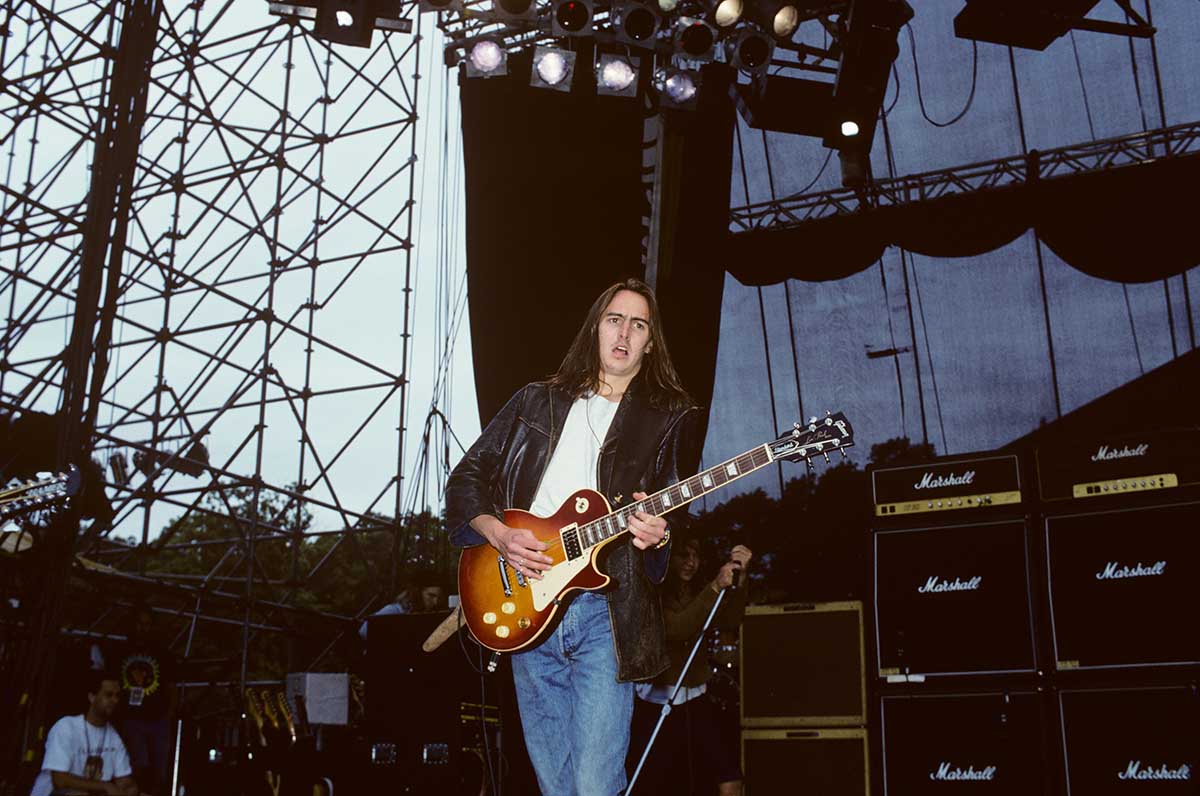

In the summer of that year, two guitarists, Stone Gossard and Mike McCready, and bassist Jeff Ament were starting down the long road that would lead to their own success. The three would congregate in Gossard’s parents’ attics, long used as a rehearsal space by the guitarist, and jam on the instrumentals that within a year would become Pearl Jam’s Ten.

There was no pressure, because they weren’t really songs. They were just song ideas, jams and that sort of stuff. It was totally cool, because at that point, it was just kind of picking up the vibe and going with it

Jeff Ament on Pearl Jam's original demos

McCready had previously played in a flashy local metal band, now defunct, called Shadow; Gossard and Ament had also played on the local scene, starting in the early '80s with the band Green River. They split up that band in 1987 to join singer Andy Wood in the band that was soon to be named Mother Love Bone.

Gossard and Ament’s aspirations for Green River had been clashing with that of their bandmates, in particular singer Mark Arm: while his model for the band was the DIY ethic of punk bands like Black Flag, Gossard and Ament drew their inspiration from commercially successful hard rock acts such as AC/DC and Kiss. (After Green River’s dissolution, Arm, along with one-time Green River guitarist Steve Turner, would go on to form the staunchly anti-corporate, grunge-pioneering Mudhoney.) With Mother Love Bone, Gossard and Ament were able to exercise their arena-size ambitions to the fullest, having found a kindred spirit in Wood.

Wood openly courted success, having set himself the goal of becoming a rock star at the age of 11. His onstage presence was flamboyant and larger than life, whether he was dressing up in feather boas and platform shoes or leaping from the stage, cordless mic in hand, to roam through the crowd while he sang.

But such behavior was in many ways a mask for the low self-esteem that had long plagued him – just as the drugs he used, often secretly and in shame, were a way to combat it. Despite an intervention by his bandmates in late 1989, and a period of sobriety on his part, Wood died from an accidental heroin overdose on March 19, 1990. It was just weeks before PolyGram Records was due to release Mother Love Bone’s first full-length, Apple.

So it was that Ten was born out of the pain of losing a friend, and as a means for the mourners to move on with their lives. When Gossard and Ament started jamming in the attic that summer, it was the first time they’d played together since Wood’s death; neither had wanted to continue Mother Love Bone without him, and neither had known what to do next.

“I didn’t know what I was going to do with my life,” Ament said in 1991, as Kim Neely recounts in her book Five Against One.

“I felt like I’d spent a lot of time getting to that point, and the fact that the rug got pulled out from underneath us right when we were about to go on the road [to support Apple] was really depressing. ’Cause that’s all I’d ever wanted to do. Making records is great, but I’d made a lot of records, and in all the years I’d been in bands, I’d never been out for three or four months, six months or a year. So when that got taken away, it was like, ‘Oh, man, I’ve got to start all over again.’”

In the end, it was McCready who reunited the former bandmates. Gossard had spent the summer after Wood’s death writing music on his own, while Ament was playing around town with several bands. On a night in June, they saw McCready playing with a local psychedelic outfit called Love Chile, and soon after Gossard gave the guitarist a call.

“He said, ‘Do you want to jam?’” McCready remembered in Spin in 2001, “so we got together and we started playing upstairs in his parents’ attic. Jeff was playing with other people at the time. I said, ‘We got to get Jeff, because you guys together are really great.’” Soon, Ament was onboard as well.

Not long after the three began playing together, they realized that the instrumentals they’d created were far from throwaways. Recruiting Soundgarden’s Matt Cameron to provide the drums, they went into the studio for a few days to record what they’d written so far.

“There was no pressure, because they weren’t really songs,” Ament told Neely. “They were just song ideas, jams and that sort of stuff. It was totally cool, because at that point, it was just kind of picking up the vibe and going with it.”

Gossard put five of these instrumental tracks – Dollar Short, Agytian Crave, Footsteps, Richard’s ‘E’ and ‘E’ Ballad – onto a tape, calling it Stone Gossard Demos ’91. The band then sent the cassette out in search of a singer and drummer. When they got the tape back from one singer, a young surfer from San Diego, they would have the song that would start their career: Alive.

When Eddie Vedder first heard Dollar Short, in September 1990, he was at work, pulling the graveyard shift at a Chevron tank farm. Gossard and Ament had given him a copy of Stone Gossard Demos ’91 after drummer Jack Irons had put the three in touch. (Irons, formerly of the Red Hot Chili Peppers, had been courted by Gossard and Ament to drum for them, but he ultimately turned them down, feeling unable to pack up his pregnant wife and leave California to devote himself to the Seattle band.) Vedder had split with the band Bad Radio earlier that year, having become aware, after four years, that their ambitions and dedication didn’t match his own.

The morning after he first listened to the demo, Vedder went surfing, the music still in his head. He recalled the incident to Neely in 1991: “When you haven’t slept for days, you get so sensitive that it feels like every nerve is directly exposed… I went surfing in that sleep-deprived state and totally started dealing with a few things that I hadn’t dealt with. I was really getting focused on this one thing, and I had this music in my mind at the same time. I was literally writing some of these words as I was going up against a wave.” As soon as he left the water, he returned home and added his lyrics to three of Gossard’s songs.

Vedder would later describe those songs – Dollar Short, Agytian Crave and Footsteps, otherwise known as Alive, Once and Footsteps (now a U.K. B-side to Jeremy) – as a mini opera. They are also known as the Mamasan trilogy, so called for the title Vedder gave the cassette that he returned to Gossard and Ament. The trilogy, as Vedder related to Cameron Crowe in Rolling Stone in 1993, stemmed from a fictionalized account of an actual event.

“The story of the song is that a mother is with a father and the father dies,” he said of Alive. “It’s an intense thing because the son looks just like the father. The son grows up to be the father, the person that she lost. His father’s dead, and now this confusion, his mother, his love, how does he love her, how does she love him?

“In fact, the mother, even though she marries somebody else, there’s no one she’s ever loved more than the father. You know how it is, first loves and stuff. And the guy dies. How could you ever get him back? But the son. He looks exactly like him. It’s uncanny. So she wants him. The son is oblivious to it all. He doesn’t know what the fuck is going on. He’s still dealing, he’s still growing up. He’s still dealing with love, he’s still dealing with the death of his father. All he knows is ‘I’m still alive’—those three words, that’s totally out of burden.”

He continued, saying, “The whole conversation about, ‘You’re still alive, she said.’ And his doubts: ‘Do I deserve to be? Is that the question?’ Because he’s fucked up forever! So now he doesn’t know how to deal with it. So what does he do, he goes out killing people – that was Once. He becomes a serial killer. And Footsteps, the final song of the trilogy, that’s when he gets executed.”

I’d never been in a situation where it clicks. It all happened in seven days… When Eddie came up he had Footsteps, Alive and Black. And out of that week came so many other things

Mike McCready

In the countless interviews the band conducted in the years to follow, it would be revealed that the truth on which Alive was based came from Vedder’s own life: he had been raised believing one man was his father, only to be told by his mother, at age 17, that his father was in fact someone else, and that that man had already died. Gossard and Ament did not know the story at the time. What they heard in the lyrics instead was a deep hurt that echoed their own.

“What he was writing about was the space Stone and I were in,” Ament told Spin in 2001 about his first rehearsals with Vedder. “We’d just lost one of our friends to a dark and evil addiction, and he was putting that feeling to words.”

A few weeks after they heard the Mamasan cassette, Gossard and Ament flew Vedder to Seattle for a trial run.

By the time Vedder got to Seattle, on October 13, he had already written lyrics to another instrumental, ‘E’ Ballad. The song was a heartbroken soliloquy to a former lover, and it is now known as Black. The band, which now included Dave Krusen on drums, would jam on this song and several others the same day Vedder arrived, heading to its rehearsal space in the basement of the art gallery Galleria Potatohead straight from the airport, at Vedder’s request. The day’s sessions soon expanded into a week’s worth of intense productivity.

“I’d never been in a situation where it clicks,” McCready recalled in Spin in 2001. “It all happened in seven days. We had worked up all the music a month prior to that with Krusen. When Eddie came up he had Footsteps, Alive and Black. And out of that week came so many other things.”

The week would produce 11 songs in all. Though most would not make it onto any recordings, the songs did include an early version of Oceans as well as of Even Flow and Release. Like his other songs, Oceans was based on people he knew, while Even Flow stemmed from Vedder’s long-running sympathy for the homeless. But it was Release, a message from Vedder to the father he never knew, that was the most personal. It would also be the only one of Ten’s songs that was written by the entire band.

“On Release,” Vedder told Neely in 1991, “everyone plugged in their guitars and started this kind of tinkling, and I started humming, moaning or whatever. And then all of a sudden it was, like, a six-minute song that totally rolled and peaked.”

Calling themselves Mookie Blaylock, after the New Jersey Nets basketball player, the band debuted these songs at a gig on October 22 at the Seattle club the Off Ramp. The following day, they went into London Bridge Studios to put the best of these songs to tape. By December, Vedder had moved to Seattle for good.

While Vedder was busy transplanting his life from San Diego to Seattle, Gossard, Ament and McCready were absorbed with a transitional project of their own: a tribute record to Andy Wood. The idea for the album, named Temple of the Dog after a line from a song of Wood’s, Man of Golden Words, had come from Soundgarden singer Chris Cornell; the one-time roommate and close friend of Wood, he too was searching for a way to purge his pain.

You almost kind of had to yell at Mike McCready to get him to realize that in the five-and-a-half-minute solo of Reach Down, that was his time and that he wasn’t going to be stepping on anybody else

Chris Cornell

“I had written Say Hello 2 Heaven and Reach Down and I had recorded them by myself at home,” Cornell said of two of the album’s tracks in Spin in 2001. “My initial thought was I could record them with the ex-members of Mother Love Bone as a tribute single to Andy.”

At this time, Gossard, Ament and McCready were recording their demo with Matt Cameron, and Cameron played them the tape of the singer’s songs. “I got a phone call from Jeff,” Cornell said, “saying he just thought the songs were amazing and let’s make a whole record.”

Cornell wrote all the lyrics and most of the music for the album, but Gossard contributed three songs of his own: Pushin’ Forward Back, which he had written with Ament during the jam sessions in his parents’ attic; Four Walled World; and Times of Trouble, which started life as the same instrumental that became Footsteps.

Starting in November, Cornell, Gossard, Ament, McCready and Cameron spent their weekends working on the album, recording in London Bridge Studios with producer Rick Parashar (who had produced the demos that got another local band, Alice in Chains, signed to Columbia Records).

Everyone involved with the album still speaks of Temple of the Dog as something special, a project that came from the heart. Gossard event told Spin, in 2001, that “I still listen to it and think that it’s the best thing I’ve ever been involved with.” But for at least one of the musicians, it also served as a big step toward becoming part of a serious band.

“I think Temple was the first full-length album that McCready ever recorded,” Cornell told Spin. “You almost kind of had to yell at him to get him to realize that in the five-and-a-half-minute solo of Reach Down, that was his time and that he wasn’t going to be stepping on anybody else. He started recording what was eventually the solo; halfway through it he got so into it that his headphones flew off, and he played half that solo without even hearing the song.”

When the album was released in 1991, on Soundgarden’s label, A&M, it would have Vedder singing backing vocals on a few tracks, and lead alongside Cornell on the song Hunger Strike. Cornell invited Vedder to sing on the album, perhaps as a welcoming gesture to the newest member of the Seattle music community. But the idea to include Vedder inadvertently came from the singer himself.

“When we started rehearsing the songs,” Cornell remembered, “I had pulled out Hunger Strike and I had this feeling it was just kind of gonna be filler; it didn’t feel like a real song. Eddie was sitting there kind of waiting for a [Mookie Blaylock] rehearsal and I was singing parts, and he kind of humbly – but with some balls – walked up to the mic and started singing the low parts for me because he saw it was kind of hard. We got through a couple choruses of him doing that and suddenly the light bulb came on in my head: this guy’s voice is amazing for these low parts. History wrote itself after that; that became the single.”

Three months after the Temple of the Dog sessions ended, Mookie Blaylock reentered London Bridge Studios with Parashar, this time to record their own full-length, for Epic Records. Had things gone differently, the album would have been recorded for PolyGram; because of the contract Mother Love Bone had signed with the label, it owned any music the band members made on their own.

But Gossard and Ament had grown unhappy with PolyGram – the A&R rep who had signed them, Michael Goldstone, had recently left, and no-one else at the label could seem to remember who they were – and had asked to be released from their contract. The label agreed to grant their request – as long as the band paid off a $500,000 debt. Goldstone, who had recently switched to Epic and who wanted to represent Gossard and Ament’s new project, proved once again to be the band’s savior: he talked his new bosses into footing a multithousand-dollar loan so the band could gain its release.

Mookie Blaylock had already gone into London Bridge with Parashar on January 29 to record a more professional demo of their best songs. This session produced the tracks that would make up the group’s first EP: Alive, Wash and a cover of the Beatles’ I’ve Got a Feeling. That same version of Alive, with an additional lead guitar overdub, was used for the full-length. The rest of the tracks would be taken from the recording sessions that began on March 27. The band had already written most of the album’s material by then, and the sessions went quickly, ending less than a month later, on April 26.

“I basically told Michael at Epic, ‘If you want us on the label this is the schedule of things that have to happen,’” Ament told Jennifer Clay of RIP magazine in 1991.

“We had a schedule of when we wanted to make a record. It was only six or eight weeks after we’d been a band. It was exactly what we didn’t do with Mother Love Bone, and that was to actually get some of the spontaneity and freshness of the songs, to get really close to them when they were written… I wanted to get back to making a record that was a little bit more raw, with a little more emphasis on getting the intensity.”

Making their first appearance on tape at this point were the songs Porch, Deep and Why Go. The latter was another of Vedder’s songs inspired by people he knew, in this case a friend who, after getting caught smoking pot, had been hospitalized.

Also based on true events was the song that, with its visionary video of a tormented teen, would finally break the band on a large scale: Jeremy. The track is based on the life of a troubled 16-year-old named Jeremy Wade Delle, who fatally shot himself in front of his English class in Richardson, Texas.

The song, which was written by Ament, was first recorded sometime in January or February; during the recording process, an outro was added that featured a cello, played by Walter Gray, and Ament on a 12-string Hamer bass. Ament played that same bass on Deep as well as on Why Go, which he also wrote and on which he debuted the instrument. McCready, when describing the 12-string part of Why Go to Jeff Gilbert in Guitar School in 1995, said it “sounded like a piano in your face. It was pretty intense.”

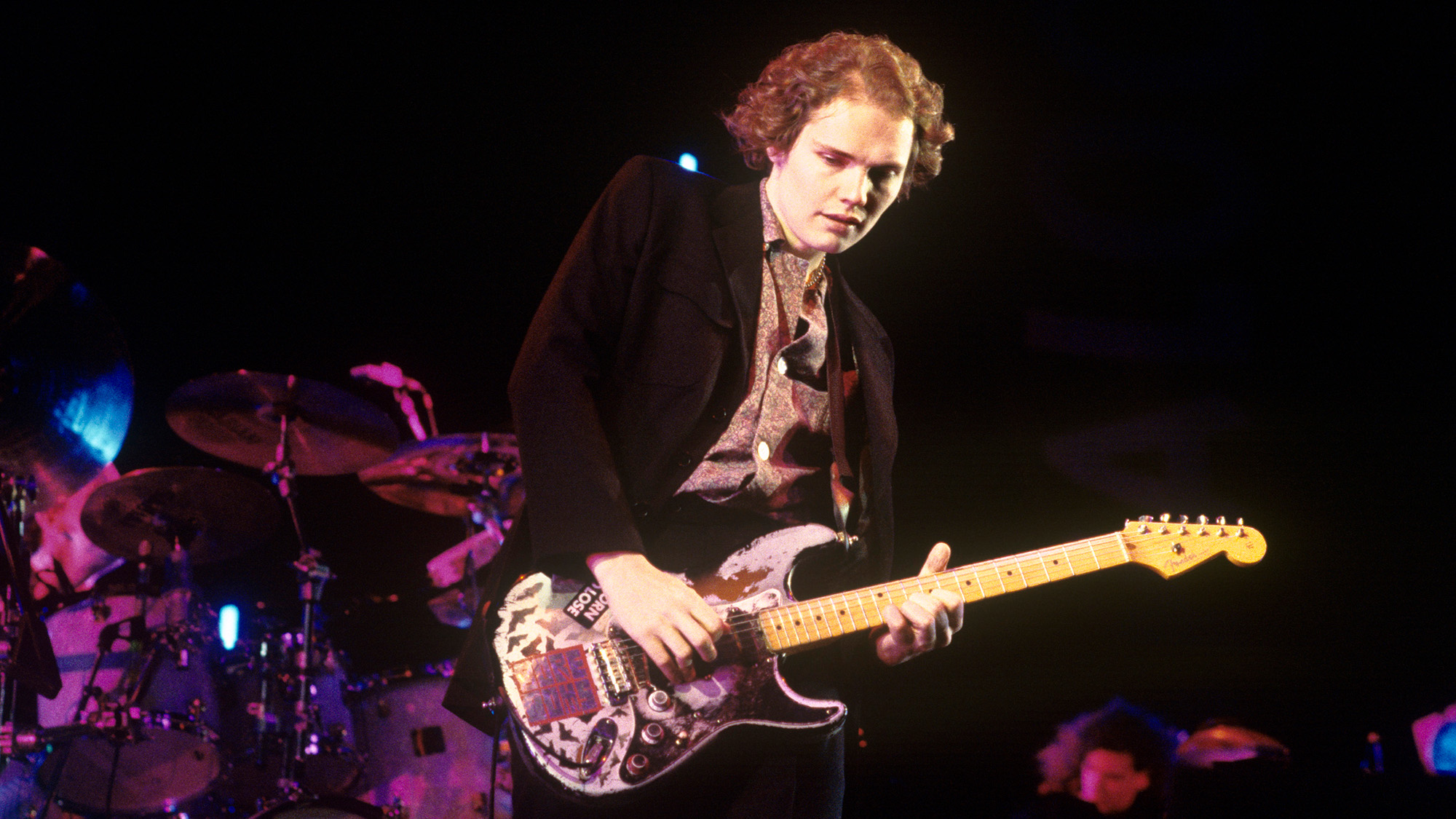

The sessions also introduced the track Garden, a sort of window into the symbiotic relationship between Gossard and McCready. Gossard was the main songwriter for Ten, and he often employed alternate tunings on his Gibson Les Paul Customs; Garden, for example, was written in a dropped-D tuning. But McCready, who played lead, kept his Fenders in standard tuning when it came to his solos.

“We’re pretty opposite as players, so we complement one another,” Gossard told Alan di Perna in Musician in 1992. “It’s a trade-off between us. You’ll hear Mike’s guitar come up for the solos, but there are a lot of songs where my rhythm parts are playing the main riff.” On Garden, Gossard’s soft lattice rhythm work provides the lead for the song’s verses, leaving the chorus and bridge to McCready’s piercing solos.

The lead riff on Even Flow was also written by Gossard – and then left to McCready to play. “Stone wrote the riff and the song,” McCready told Guitar School’s Gilbert in 1995. “I think it’s a D tuning. I just followed him in a regular pattern.

I tried to steal everything I know from Stevie Ray Vaughan and put it into Even Flow. A blatant rip-off

Mike McCready

“That’s me pretending to be Stevie Ray Vaughan, and a feeble attempt at that,” McCready continued. “I tried to steal everything I know from Stevie Ray Vaughan and put it into that song. A blatant rip-off.” Stevie Ray also provided the inspiration for McCready’s part in Black, as the guitarist told Gilbert: “That’s more of a Stevie rip-off, with me playing little flowing things. I really thought the song was beautiful. Stone wrote it, and he just let me do what I wanted.”

To bookend the album, the band chose a moody, bass-driven instrumental swatch that has come to be known as Master/Slave.

“As I recall, I think Jeff had, like, a bassline,” Parashar said when contacted for this article. “I heard the bassline and then we kind of were collaborating on that in the control room, and then I just started programming on the keyboard all this stuff; he was jamming with it and it just kind of came about like that.”

Parashar would collaborate with Ament in another, equally crucial way during the recording. “He liked to have the low-end,” remembers the producer, “and the monitors weren’t giving him a lot of the low-end that he was used to and liked to feel.” To rectify the situation, Parashar devised a special recording situation for several of the songs: “We put his amp out in a big room,” he remembers, “and I think he wore headphones and also sat in front of his amp.”

The band would resort to a similarly unorthodox measure during the mixing stage. In June, Vedder, Ament, Gossard and McCready flew to England to mix the album with Tim Palmer. (Krusen had left the band the previous month because of personal reasons most likely involving alcohol abuse; by August, his spot would be filled by Dave Abbruzzese.)

Palmer, who had mixed Mother Love Bone’s Apple, had tired of L.A. studios and had wanted to relocate to England, where he had started his career. He chose Ridge Farm Studios, a converted farm in Dorking, England, which, when contacted about this article, Palmer described as being “about as far away from an L.A. or New York studio as you can get, and I don’t mean distance! You have to try very hard to find other human beings, but there are plenty of sheep.”

Such an isolated locale resulted in the band taking some creative steps when mixing. In the finished album’s liner notes, Palmer is credited with playing the fire extinguisher and the pepper shaker. These “instruments” actually pop up as percussion on the song Oceans.

“I used the pepper mill as a shaker and used drum sticks on the extinguisher as a sort of bell effect,” Palmer says. “At about 30 seconds into the song you can hear the pepper shaker on the left and the fire extinguisher on the right. It is all fairly subtle stuff, really. The reason I used those items was purely because we were so far from a music rental shop and necessity became the mother of invention.”

Everybody in the band was going through this kind of rebirth, and it went from the burdens of being alive to appreciating being alive

Eddie Vedder

The rest of the mixing was much more straightforward, with most of the music having arrived ready to mix. Palmer did, however, make a few additions, such as finishing up the closing guitar solo to Alive. “We set Mike McCready up to record in the control room,” Palmer remembers. “His amp was in the live room. He did a couple of passes at the solo and I put together a composite for him.”

At this point Palmer was satisfied with the solo; McCready – who described the part to Gilbert in Guitar School as “Ace Frehley’s solo from She, which was copied from Robby Krieger’s solo in the Doors’ Five to One” – was not. “He had another go at it,” Palmer says, “and got it right away. There was no piecing together to do; it was one take.”

Palmer also did some tweaking to Black. “I was never happy with the way the intro guitar sounded,” he says, “so I EQ’d the whole top of the song really small and radio-sounding. When the bass comes in it is a nice feeling to finally hear all the low-end.”

When the album came out, on August 27, 1991, it had become a reaffirmation of life, even in the face of great hardships. “It just turned out that way,” Vedder told Neely in Rolling Stone in 1991. “Everybody in the band was going through this kind of rebirth, and it went from the burdens of being alive to appreciating being alive.”

By now, the band had changed its name to Pearl Jam. (The band claimed at the time that the name came from the hallucinogenic jam Vedder’s great grandma Pearl used to make, though the story is most likely a fabrication). But in tribute to their original moniker, they named the album after Mookie Blaylock’s jersey number: Ten.

Though Ten would eventually go Platinum several times over, it didn’t hit big right away. Instead, the album sold the old grassroots way: through word of mouth. One kid would turn his friend on to the band; the friend, once converted, would tell his friend, and so on. The song that spoke to these kids the most in the early days was Pearl Jam’s first single, Alive.

With its chorus of “I’m still alive,” the song was adopted as an anthem by a generation of disaffected teens. It regularly reduced fans to tears at shows; many of them started wearing the stickman Ament drew for the Alive EP cover as a tattoo.

Vedder, cognizant that the chorus spoke of guilt and self-doubt rather than of self-affirmation, would be conflicted by the song’s misinterpretation – just as he and the rest of the band would struggle with their steadily increasing fame.

“Everybody writes about [the song] like it’s a life-affirmation thing,” Vedder ruefully told Cameron Crowe in Rolling Stone in 1993. “It’s a great interpretation. But Alive is…it’s torture. Which is why it’s fucked up for me.” For the legions of disillusioned kids who were touched by it, however, Alive was a beacon, shining a bright ray of hope into the darkness of their lives.