The Who: Pete Townshend talks Tommy, Quadrophenia, Who's Next and more

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

From the ruins of his failed rock opera rose the Who’s greatest album, Who’s Next. Now, with the release of the group’s new record, Endless Wire, Pete Townshend discusses the triumphs of Tommy and Quadrophenia and reveals the secret history of Lifehouse, the lost masterpiece that continues to haunt his music.

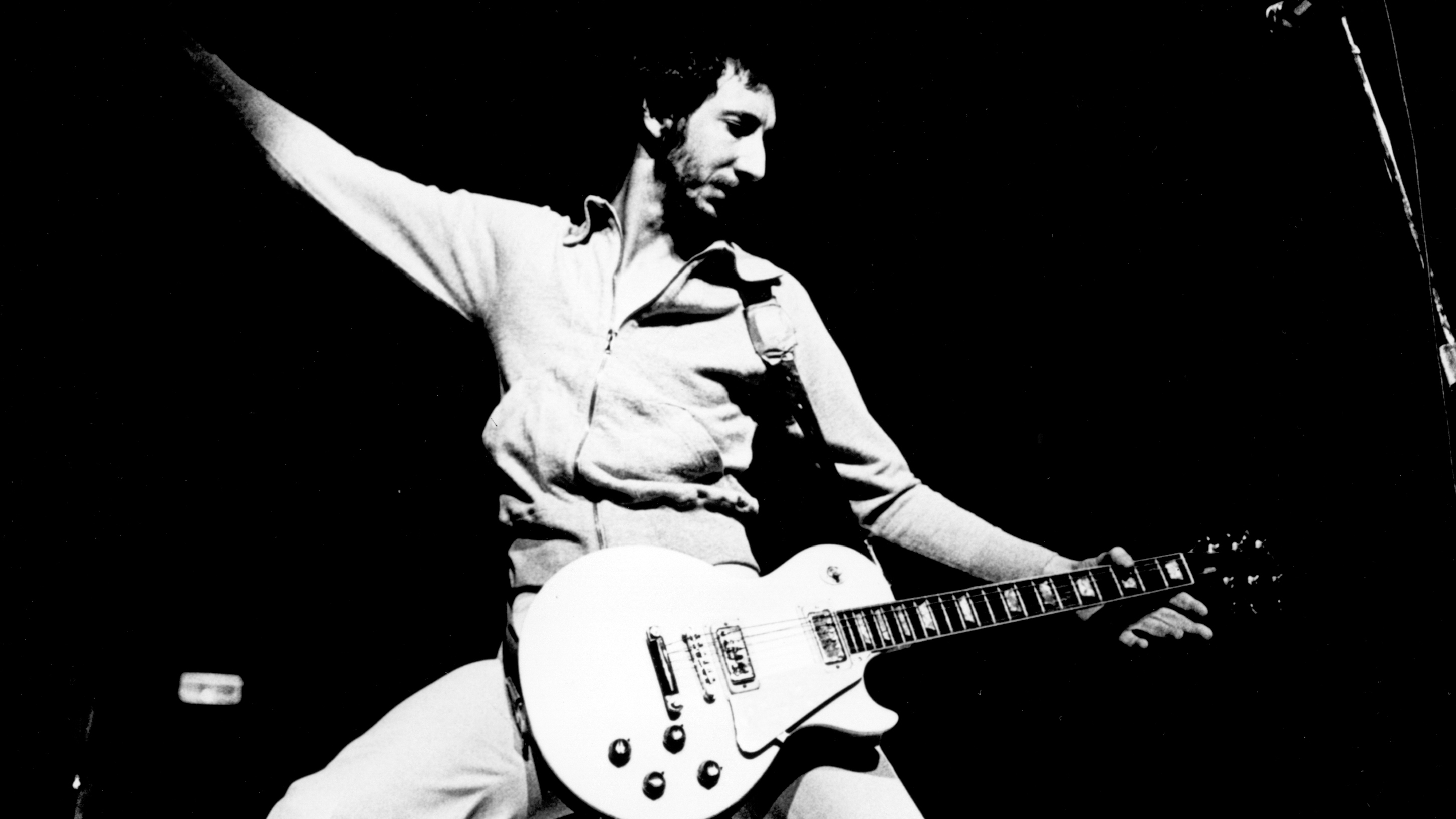

How do you top your best work? It’s a question most successful musical artists face throughout their careers. Pete Townshend is no exception. As the Who’s guitar-smashing auteur, Townshend is responsible for penning the band’s greatest hits, from early pop singles like “My Generation” and “The Kids Are Alright” to full-scale rock operas such as Tommy and Quadrophenia.

Yet Townshend’s, and the Who’s, unarguably finest work was presented on 1971’s Who’s Next. The album is packed with many of Townshend’s best-known songs, including “Baba O’Riley,” “Won’t Get Fooled Again,” “Going Mobile,” “Bargain” and “Behind Blue Eyes,” and features some of strongest and most inspired performances that Townshend, singer Roger Daltrey, bassist John Entwistle and drummer Keith Moon ever delivered.

So it is perhaps not entirely surprising to find Who’s Next is referenced both musically and thematically on Endless Wire (Universal), the first album of new material that the Who (now just Townshend and singer Roger Daltrey) have released in 24 years. The new disc even kicks off with an arpeggiating synth pattern, in the song “Fragments,” that recalls “Baba O’Riley.”

“The similarity was intentional,” says Townshend. “I wanted to make the opening of the CD evoke the Who’s Next album, which most people regard as our best. I wanted to challenge it, audaciously.”

Not only challenge it but draw resources from it, like a contender preparing for a championship title in the champ’s own gym, and with his trainer to boot. Central to this challenge is the Endless Wire track “Wire and Glass,” a mini-opera some 18 minutes in length that comprises 10 song fragments. Not coincidentally, its plot, central character and narrative elements are extensions of an earlier rock opera, a failed project from 1970, the music of which formed the basis for Who’s Next.

Lifehouse, as the project was called, was to be the followup to Tommy, the Who’s 1969 rock opera about a deaf, dumb and blind boy whose disabilities lead to his spiritual enlightenment and rise as a post-World War II messiah (see sidebar). In the year after Tommy’s release, Townshend—fueled by the album’s success and his rise as one of rock’s most important creative forces—began to conceive and write Lifehouse as a futuristic parable for the post-hippie times.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

As originally conceived, Lifehouse presents an Earth in which most of civilization lives underground, where inhabitants wear suits that connect them to the Grid, a lifeline controlled by a dictatorship. The Grid provides not only food and air but also virtual reality, allowing citizens to live away their existence in a persistent dreamlike state that satisfies their every emotional and physical desire. Enter Bobby, a rebel computer programmer who still lives above ground. Hacking into the Grid, he steals the personal information of several hundred inhabitants and uses the information to compose musical portraits of them. These Grid dwellers eventually join Bobby at the Lifehouse, his commune, where performances of the works created from their data provide a passage to spiritual fulfillment and ascension to paradise.

While the ploy seems simple enough, particularly in today’s internet-driven culture, it proved to be the project’s undoing; no one aside from Townshend could make sense of the storyline. Musical technology plagued the project as well. Townshend wanted the Who to be accompanied by sequencer-driven keyboard synthesizers that would follow along with the band in real time, but the technology didn’t exist and wouldn’t for a couple more decades. Ultimately, Townshend had to settle for the band members dutifully playing along to previously recorded backing tracks on “Baba O’Riley” and “Won’t Get Fooled Again,” trying their best not to fall out of synchronization with the precise rhythms of the electronic score.

Although Townshend abandoned Lifehouse, references to it creep up in “Gridlife,” the musical project within his 1993 solo rock opera Psychoderelict, as they do in Endless Wire, where the protagonists hatch a plan to compose music from personal data fed into a computer program. Closer to the original point, in 1998 Townshend created a radio play of Lifehouse using music from his unfinished rock opera; it was broadcast on the BBC in December 1999. For a project that caused him such personal distress, Lifehouse has been an almost career-long obsession for Townshend. “I’d obviously put it in a back pocket to produce later on,” he says.

In the following interview, Townshend discusses the origins of his rock operas Tommy and Quadrophenia and reveals the near-catastrophic effects of his struggle to create Lifehouse.

GUITAR WORLD A story told on that scale requires a more elaborate narrative than a three-minute pop song. How did you develop the story for Tommy, and what were your inspirations?

TOWNSHEND I’d read Siddhartha [Herman Hesse’s 1922 novel about an Indian man’s spiritual enlightenment] and a few things like that, and I had this idea of somebody on a spiritual journey; the bit about Tommy being a pinball wizard came later. The fact that Tommy was deaf, dumb and blind was simply about being spiritually shut down.

But, you know, the story was a kind of side issue to the whole project. It was just a thing with which to create the music and then to present it. I don’t think any other band could have gotten away with that, presenting an album like that as a narrative story. I think Tommy worked because the Who was such a great band. I think if the Who had been a naff band, it would have flopped.

GW And in fact, Tommy made the Who one of the biggest bands in rock and roll. But that, in turn, made you distraught about the level of success you achieved. Why did you have a problem with it?

TOWNSHEND I think I was worried and anxious that the connection between the Who and its audience was being eroded by the band playing to big audiences. I felt that the elegance of pop music was that it was reflective: we were holding up a mirror to our audience and reflecting them philosophically and spiritually, rather than just reflecting society or something called “rock and roll.”

And that all that was going to be lost by playing large-scale things like Woodstock, which turned us into superstars. And in some ways it was wonderful that we went from being a band with a predominantly male following to one where Roger seemed to be a kind of Rock Sun God and we had a few women in the audience for a change.

But in other ways it was disarming because the natural easy connection between me, as the writer, and the audience, was broken. The feeling I had was that we were starting to become in a way like Tommy: we started to become more deeply deaf, dumb and blind to what was actually happening to us.

GW You attended Ealing Art College as a teenager. It was there that you became familiar with some of the concepts you later employed with the Who. Deconstructionism, for example: you’d smash your guitars onstage, making it actually one of the most anticipated parts of a show. How much did your art college training play a role in your rock operas?

TOWNSHEND I think it had everything to do with everything: the Who and all our music. Because it would allow someone to have the ability—maybe the arrogance—to set himself up as a reflector of society, or in my case, of our audience. I went so far in the early days as to call the Who “pop art” because I wanted to identify with those people who looked at the condition of society and the world, the climate in which popular ideas were gathered, as well as fashion and style and image and all of those things.

GW Give me an example of how your art college training affected your music and your ability to be, as you say, a “reflector” of your audience.

TOWNSHEND Let’s just take a basic art school course: If you’re trained to draft images, what you’re trained to do is capture not the truth, not an impression, but rather geometric precise representations of what it is that the eye sees. It’s an absolute reflection.

So it is from that pure place that I wrote those songs. Who is it reflecting to? It’s reflecting to the subject. As an artist, you’re purely there to perform a very mundane, simple act. It’s not about caricature. This is about truth.

GW So when you felt the Who were no longer connecting with their audience after Tommy’s success, the bond between artist and viewer was broken. You were no longer able to reflect them.

TOWNSHEND Yes.

GW And it was at that point that you began to develop the rock opera Lifehouse. Was Lifehouse conceived as a story that would address this sense that you and your audience were losing touch with one another?

TOWNSHEND Lifehouse contained a fear of losing that easy identity with our audience. But it was also a recognition that there was nothing more important to me than the simple art of rock music: of making something that unites the listener and the player. Because that moment has lasting value for the person that’s heard it.

GW Throughout the years, you’ve been portrayed as having been unable to communicate the theme of Lifehouse. Is that a fair view?

TOWNSHEND No, I think I communicated it perfectly well. I think what people found difficult to understand was the connection between one metaphor and another—one example being my Grid, my internet, as a metaphor for global conspiratorial control. In fact, that metaphor is something of a problem today when I explain Lifehouse, because the Internet has turned out to be almost the opposite of that. But that’s how I saw it. I saw the internet as being something which would allow power mongers to control us, and that we would willingly go to that if it promised us salvation—if it promised to show us who we were and let us find ourselves as we had, uniquely in our generation, through rock music.

GW So part of the problem was that people couldn’t comprehend the Grid, because there was nothing comparable to it at the time.

TOWNSHEND Well, television existed. And television in the U.K. has always been, up until recently, run by the government. All I was really saying was, “Well, you know what we do with TV: we sit in front of it, and we turn the lights out, and we watch it, and we don’t listen to pop music.” [laughter] “Well, imagine that…a bit more. So instead of turning on the TV and watching a soap opera, you experience a soap opera! Get it?”

GW In terms of the Who, can you give me a real-world parallel to the Grid that demonstrates how someone could use the group to control people?

TOWNSHEND For me as a young writer, to write a song with “My Generation,” I reflected what people like me felt. But I also put their situation up on the radio where other people could see it—people who might take advantage of that information and use it, and even the song, for their own political aims.

And the danger was already there. You know, the song “Teenage Wasteland” is about the absolute desolation of teenagers after the second Isle of Wight festival, and after the Woodstock festival, where everybody was smacked out on acid and 20 people had brain damage. The dichotomy was that it became a celebration. “Teenage wasteland! Yes. We’re all wasted!” People were already running toward the culture and its promise of salvation. But not everyone survived.

And so Lifehouse was kind of going in that direction, starting to think, What are the problems in this? And for me, the main thing was that I didn’t want to lose that sense that I had at the time that music was my redemption, my salvation—my life. Music was the only art that mattered to me. And at the time, it looked like it was going to be lost.

GW Apart from the difficulty of conveying the plot to people, why was Lifehouse so difficult to create?

TOWNSHEND It was fucking awful. I had a—well, “nervous breakdown” is probably too big a description of it. But I had a breakdown due to nervous exhaustion. The problem began because Kit Lambert [the Who’s manager] wasn’t available to me at the time I was working on it; he was in New York. Kit had always been my friend, and my pal. He was very supportive throughout Tommy, but we were a little bit estranged at the time of Lifehouse, because his drug use had gotten a bit exotic.

But then Kit called and we went to New York to do work on the songs I had completed. And I was delighted because I thought, Kit’s back, and we’re going to get this together now.

GW But it didn’t work out that way?

TOWNSHEND No. We’d been in the studio for about six days, and it was going very well. But one day I went up to his hotel room, and as I was going in, I could hear him stamping around angrily, talking to his secretary and his butler and calling me “Townshend.” And as I walked in, he said “Oh, hello, Pete.” But I knew what was happening: when I’m not doing what people want me to do, I’m this arrogant shit called “Townshend” and people hate me. And I started to kind of come apart. It really affected me.

What actually happened in that moment is that I had a classic, extreme, psychotic New York anxiety attack. You know, I got this welling of energy, which I think you can only get in New York, and I started to hallucinate. And I thought, I must get some air. And I stumbled towards the window, which was open, on the 24th floor. And Kit’s butler just grabbed me like that, just as I was about to jump out.

I thought Kit was going to help get Lifehouse going. And I suddenly realized that he was very, very angry with me, and didn’t like me, and thought I was ... anyway ... whatever. So I decided to leave: I went back to London and let the whole thing go. So for me, bearing in mind how much energy I put into it, what was important for me to learn, though, at that age, was that omnipotence can lead to a certain arrogance that may in turn produce alienation.

GW Do you think Kit felt alienated from the project?

TOWNSHEND Yeah. He had a problem with it. At that time I was still having great difficulty with my role in the band. I had taken over creative control, but I wasn’t willing to pay the price of the alienation that came with it.

GW Lifehouse was your first roadblock as a working composer. You were the guiding force for the Who, and I wonder, did that change you dynamic with the band? They had looked to you to be the one who brought the creative materials, to came up with the ideas, and then you had this setback. Did it shake their faith in you?

TOWNSHEND No, it affected me much more than them. You know, all I can say about the band—and even Kit—is that everybody was just fantastically supportive. You know, I think I just took on too much. I took on far too much.

GW Looking back at Who’s Next as the net result of Lifehouse—it seems to me a fair outcome. It’s a great album; many would say it’s the Who’s best. All things considered, were you happy with it?

TOWNSHEND Yeah. I was delighted with it. I was relieved to have anything at all, and it felt like the Who’s first proper album. It felt uncomplicated and simple, and I didn’t care that the story had been lost. And I just loved the way the songs sat together.

GW Compared to Lifehouse, Quadrophenia is a much simpler storyline: a few days in the life of an alienated London boy—a Mod, like the Who’s earliest fans. Did your problems achieving Lifehouse affect your decision to keep Quadrophenia’s plot and character “closer to home,” so to speak?

TOWNSHEND Yeah, very much. The fact of the matter is that when I wrote Quadrophenia, I was writing with the benefit of hindsight. In Tommy, I had failed to nail down, properly in the songs, the drama. It needed explaining, and there were some holes in it which had to be filled in. And in Lifehouse, I just fuckin’ failed, period.

So with Quadrophenia, I decided to get a much more loose line. I did that thing that one does if one’s working on a short story, to take a glimpse, a slice of life, and say, “This is three days in the life of a boy. That is all, and that will do.” And inasmuch as I was trying to deal with the whole notion of the music reflecting the audience, as I had in Lifehouse, in Quadrophenia it was absolutely literal: The kid sees the four members of the band, and he sees something of himself in each one. The band reflects something—four facets—to him. And there you have it. That’s the musical analogy.

And that what’s really going on for Jimmy. He’s going through a very normal, very unspectacular childhood, taking a load of drugs, getting off his head, being a complete shit in many ways, but finding himself on a rock in the middle of the sea at the end, looking for God, asking—crying—for help, for something to happen to him that is of value, because he feels that nothing that around him really means anything.

GW Does Quadrophenia reflect your own feelings of alienation, either as a child or after your problems with Kit Lambert on Lifehouse?

TOWNSHEND No, no. I don’t think so. I’ve never felt alienation to that extreme level of Quadrophenia, but I could see it all around me. A lot of the boys that used to come and hang out around the Who in the early days were so-called Mods. But you know, they became Mods because they felt so alone. And some of them were emigrees, some of them were kids from Ireland that had been sent over at 16 to make money.

GW To send back home?

TOWNSHEND Yeah. And you’d find out that, not only was the dad gone but the mother was gone as well, and they were living with an uncle or an aunt or a grandfather. Weird shit. Or you find out that both parents have been killed in the war. That kind of thing. And they were all drawn together by this disaffection, by this—damage.

And my sense of alienation, what enabled me to write for them, was that I could see how it would turn into anger for a lot of them. My dad was still alive, and he was a nice guy. And I loved him, and adored and worshipped him to some extent. But I never realized that he was a classic post-war emotionally unavailable male. My dad was a soldier. He was in the RAF, and when the war was over, he ran into romance and escape, and music and laughter and fun. I just kind of got left behind.

And that leads to a lot of anger, as well as misogyny, because we look to the women in our lives to deliver everything that we haven’t had from our fathers. And when it fails, we blame mom. My mom was there, and although she fucked up all over the place, and she said things to me that were very hurtful and careless, you know, when I look back, I see somebody that was very much involved in my life.

So what Quadrophenia is about, to some extent, is that men may be abusive toward women. But the abuse lies in the fact that the people that we’re in contact with where we’re particularly young tend to be women. And if those women are damaged by men, we inherit the damage.

GW It’s cyclical.

TOWNSHEND Yes.

GW Your generation also suffered the psychological fallout from the war and the effects of the London blitz.

TOWNSHEND And often the fathers were dead. You have to remember how many men were killed, particularly towards the end of the war, and the fact that I was born in May [1945], and it was the month that the war ended. When I was growing up, I was very used to seeing my friends’ dads sitting like this [sits dead still, looking warily from side to side]. You know, like, “If I don’t do anything, I’ll be all right.”

And the generation that fought in World War II had this sense that, “We gave you the right to exist, you little fuckers. All you have is the duty to thank us!” And that we were responsible for their torture.

So with Quadrophenia, I was really, really clear about what I was doing and what I was working with. Jimmy was sort of a composite of kids I knew. I just went back to look at them again and recreated it. It’s one of the clearest pieces I’ve ever written.

GW What’s striking about Quadrophenia is how bleak Jimmy’s situation is. In both Tommy and Lifehouse there is a moment of spiritual awakening and of social bonding. Jimmy, on the other hand, is alone and aware of his isolation. Even his psyche is fragmented into four isolated aspects.

TOWNSHEND You know, in a weird way, Quadrophenia should, in context, have come before Tommy. Quadrophenia was an attempt by me to talk about how, in the Who’s early career, we and our audience, through disaffected heavy male-oriented rock and roll, began to feel spiritually empty. And that gave birth to the experimentation with drugs and Indian mysticism. That kind of leads into Tommy.

In a sense, Tommy, Lifehouse, Quadrophenia—they’re all about spiritual emptiness. You know, it runs through everything I’ve written, and I think it’s why my work has struck a chord with people. Because it’s all about spiritual malaise in macho clothing. People approach it because there’s something on the surface of it that they like or respond to. When they go a bit deeper, they find this tremendous frailty there, and they respond to that as well.

GW Music is salvation to Tommy, Bobby, Jimmy…to all the characters you’ve created. You said earlier that music was your salvation. In what way?

TOWNSHEND When I grew up, what was interesting for me was that music was color and life was gray. So music for me has always been more than entertainment. Entertainment came out of this thing called a television, and it was gray. Most of the films that we saw at the cinema were black and white. It was a gray world. And music somehow was in color. And that’s where I discovered me; I found me in there. And that accounts for a lot of my passion and optimism and what has kept me going and kept the Who coming back. It’s my sense of, We can do this! We can get through this thing, and we’ll make such wonderful music together.

Christopher Scapelliti is editor-in-chief of Guitar Player magazine, the world’s longest-running guitar magazine, founded in 1967. In his extensive career, he has authored in-depth interviews with such guitarists as Pete Townshend, Slash, Billy Corgan, Jack White, Elvis Costello and Todd Rundgren, and audio professionals including Beatles engineers Geoff Emerick and Ken Scott. He is the co-author of Guitar Aficionado: The Collections: The Most Famous, Rare, and Valuable Guitars in the World, a founding editor of Guitar Aficionado magazine, and a former editor with Guitar World, Guitar for the Practicing Musician and Maximum Guitar. Apart from guitars, he maintains a collection of more than 30 vintage analog synthesizers.