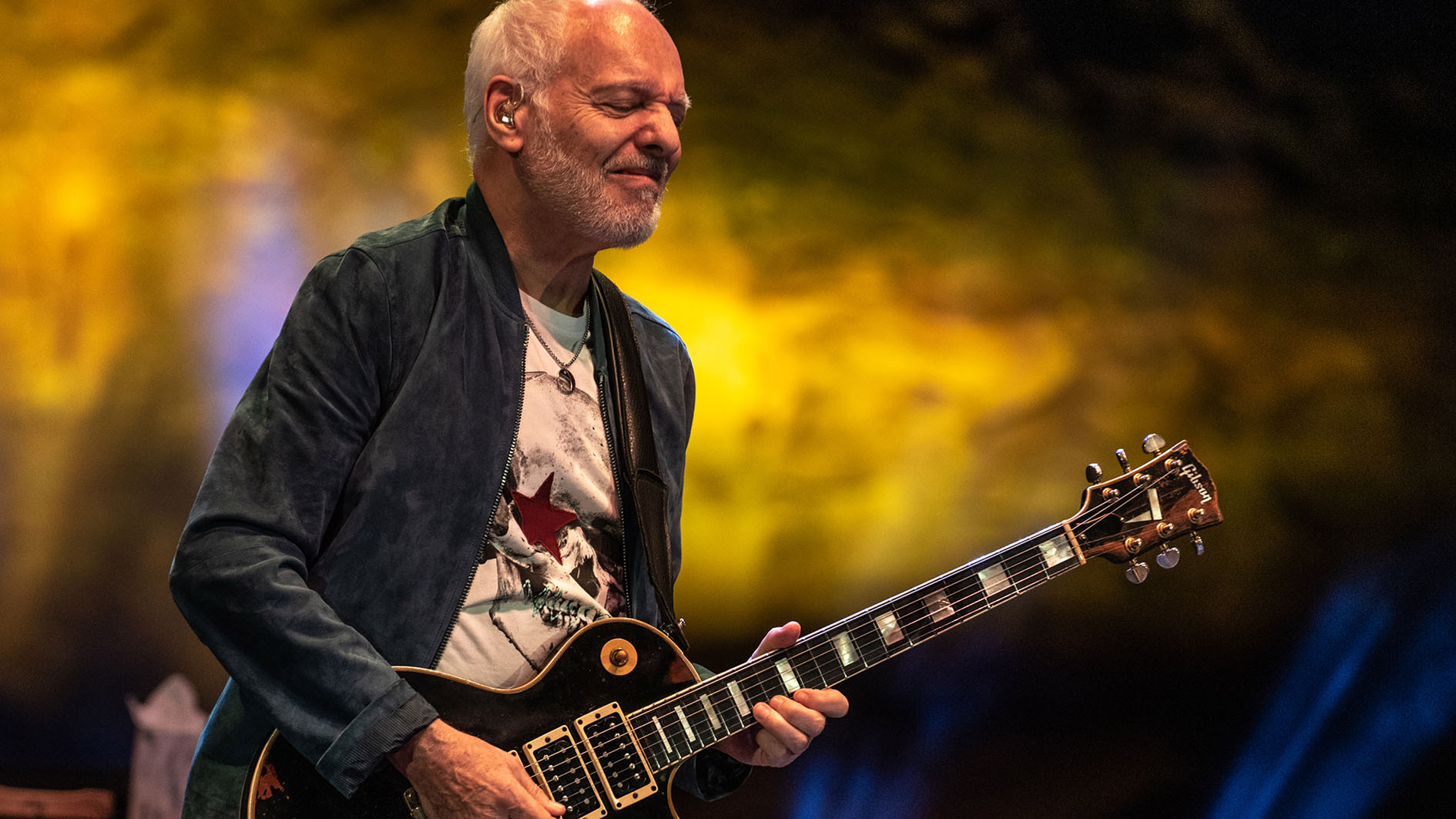

Peter Frampton: "I might not be playing live in a couple of years, but I’m going to be battling on and recording... I feel positive about the future"

The guitar icon looks back at the triumphs and knocks of his career, into the eyes of his illness, and onto the music still to come...

Most farewell tours are not to be trusted. From KISS to Mötley Crüe, long-time observers of rock will know the routine: the valedictory arena shows, the two-year itch, the reunion album, then business as usual. But when Peter Frampton says goodbye to the live stage, the veteran guitarist truly means it - however desperately he wishes he didn’t.

News of Frampton’s situation can’t have escaped you. Nine years ago, the guitarist was newly into his 60s, and hiking up a mountain with his son when he found himself strangely fatigued. Back then, he dismissed it as the inevitable wear-and-tear of aging. But when the guitarist began struggling to climb stairs and lift suitcases, then fell down repeatedly on stage in 2015, he visited a neurologist and had his fears confirmed.

Inclusion Body Myositis (IBM) is a muscle-wasting condition that weakens limbs and threatens mobility. The symptoms grow progressively worse and there is currently no cure.

“It was a devastating period,” reflects the 69-year-old family man, “for us all.” But those same observers of rock will also know that Frampton is not a man to shrink from a battle. From his teenage band, The Herd, to the visceral blues-rock of Humble Pie with Steve Marriott in the late 60s, and onto a solo career that peaked commercially with 1976’s 11-million-selling Frampton Comes Alive!, there have been plenty of triumphs.

But as Frampton reminds us, if he can return from car crashes and career wilderness, then he can fight back from this diagnosis and keep making music, somehow, somewhere.

Every live show you play must mean so much to you now?

When I turn my back and walk off the stage - I don’t have a dry eye at that point

“Yes, and the audience really add to that feeling. We did about 50 shows here in the States, and there’s an incredible warmth that’s coming from them towards us on stage. It’s like they’re trying to heal me. There are no words to explain that particular feeling. It’s sad. It’s happy. It’s everything.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

"But I can’t lose it on stage, because I have a whole show to do. So I don’t say goodbye at the end. I wave. And I think that’s the moment. When I turn my back and walk off the stage - I don’t have a dry eye at that point.”

Will you be strict with yourself when the time comes to stop?

“Well, most artists are perfectionists, or think they are. For me, I’ve never gone on stage unprepared or feeling like I needed to practice more. I’ve always gone on stage at the top of my game. Or tried to. Done everything possible.

"Last year, I said to my manager that I don’t want to be the guy that goes out on stage and people say, ‘Well, he’s not as good as he used to be.’ I’m not that guy. I know that poor Keith Emerson - who was a dear friend - had some hand problems, and that was awful, that he started getting criticized for his playing.

"I don’t want that for me. I can’t ever go on stage knowing that I’m not going to be able to play my best.”

When it comes to your playing, can you feel the effects of the IBM yet?

“Very, very slightly. It’s more the fretting hand that’s affected. The left side is ahead in the progression of the disease, more than the right. Luckily, my left hand is doing really well, and I’m sure for the rest of this year, I’ll be okay.

"Also, when you’re playing guitar, you don’t stand on two feet: you tend to favor one leg or the other. Well, the leg I’ve always favored is my left. So even though IBM affects the left side more, that leg is still pretty strong.

"So I’m doing good. I’m on a drug trial. I’m in a control period right now. I’ve had testing done and then, in March before I come over to see you, I start taking the test drug. That’s for 10 months. So we’ll see how we do.”

Which guitar techniques is your condition likely to threaten?

My playing has become more soulful – I don’t know if that’s because I treasure every moment I can play, or just that I love playing

“I think, actually, some chords are becoming a little temperamental for me. It’s because you use more fingers on the chords than you do on single notes. That’s the only area where I’m slightly [concerned] - but I have another guitarist to play the chords. Adam Lester is wonderful.”

Couldn’t you find a way to adapt your guitar parts?

“Well, they are what they are. It would be difficult to simplify them. I think my playing has become more soulful - I don’t know if that’s because I treasure every moment I can play, or if it’s just that I love playing.

"And I’m going to go on playing. I might not be able to play in front of an audience in a couple of years, but I’m going to be battling on and recording. And with recording, you can touch things up a bit. So I think I’ll have a longer recording life than I will a ‘live’ life, as it were. I feel positive about the future.”

The Les Paul Custom is pretty bulky - might you need to make a change?

“Well, it’s funny you should say that, because most Les Pauls are beasts. My Custom - which is actually a Black Beauty from ’54 or ’55 - is all mahogany, no maple top. So it should be so heavy, but it’s not. It’s much lighter than most Les Pauls, so I lucked out.”

Have you been bringing that famous Custom on tour?

“Yeah. People say to me, ‘You’re not gonna take that on the road, are you?’ I laugh and say, ‘Well, it survived an air crash!’ It would be so wrong not to play it. Y’know, to leave it at home after all it’s been through.”

Do you think you’ll adapt your rig to offset the condition?

From when I was 16... it’s been up and down, but it’s been a lengthy career. I have to be thankful for the incredible time I’ve had

“Well, the rig’s been the same for 20 years, so it’s very hard to change at this point. I mean, when I record, I’ll use anything - a Pignose, a Marshall 200-watt, anything in between - it doesn’t matter, whatever the sound needs. But on stage, I have to approximate all those different sounds from the records, because I’m a sound guy. I’m just so fastidious about sound.”

What gear have you been using live?

“Well, the backline is wet/dry/wet - three Marshall 4x12 1960BV cabs with the Celestion Vintage 30s. I have an early 70s Marshall 100-watt head that basically is my main sound. But then I have other preamps that I switch in, like an Egnater M4 modular preamp, which is a clean sound, and a ’65 Bassman head.

"So their preamps go through the Marshall back-end, and I can choose or have all three at once if I want - which is overkill, you wouldn’t do it often. I’ve always had Leslies, but I’ve got two now, so they’re in stereo, which sort of freaks me out, it sounds so good. Then I have a lot of pedals [including Klon Centaur, Fulltone OCD and Electro-Harmonix POG] and an Axess FX-1 MIDI switcher pedal.”

It’s impossible to forget Humble Pie - which albums are you most proud of?

“Well, I still think Rock On was the best record we made, and the live album, Rockin’ The Fillmore [both 1971]. That’s where my guitar style came together - that period. Due to Steve being more into blues, country and gospel, that opened my eyes, and I got much more into blues, mixing it with my lyrical jazz influences that I’d studied with The Herd.

“Steve and I were both huge fans of each other. Ever since I saw him with the Small Faces doing Whatcha Gonna Do About It on Ready Steady Go!, I wanted to play guitar with that guy. And be careful what you wish for, y’know? Obviously, we have the other side of Steve that wasn’t so easy to get along with. But you kind of pushed that away and just concentrated on the good. Which was phenomenal.

We were a very adrenalized band. We rocked from the second we walked on stage to the second we walked off

"I’ve never played with anybody that can sing like that. I don’t know where it came from. This tiny, diminutive figure with this huge personality and voice. It was all-encompassing. There was so much to learn from him.”

How rocking were those Fillmore shows from your onstage perspective?

“We were a very adrenalized band. We rocked from the second we walked on stage to the second we walked off. It was the best experience of being in a band ever, for me. People probably don’t think this, but I enjoyed every moment I was there. I had to move on and do my own thing [in 1971]. But Humble Pie was definitely responsible for me putting my guitar ideas together.

"I remember, after one show with them, saying to myself, ‘I’m actually me now. I’m not just me copying everybody’. Which is a great feeling.”

Fillmore West was also where you discovered the Custom, right?

“Yeah. We were doing four nights in 1970. I’d just swapped an SG for a 335, thinking I wanted a more ‘brown’ sound. I didn’t try it with Humble Pie before I went on stage. And the levels were so loud that when I turned up for my solo, it just fed back. So my solo was ‘woo-woo!’ Very avant-garde.

"My friend Mark Mariana came up after and said, ‘I couldn’t help noticing you were having trouble up there. Would you like to try my Les Paul tomorrow?’ I said, ‘Ah, I’m not big on Les Pauls. But anything would be better.’ So we met at the hotel next morning. Incredible guitar. I played it that night, my feet didn’t touch the ground, and when I came off, I said, ‘There’s probably no chance, but would you sell this guitar?’ He said, ‘No, I want to give it to you.’”

Do you still rate the playing on Frampton Comes Alive!?

“Oh, of course. I occasionally have to listen to it, because it’s on the radio, and there’s some good playing on there. Why did my trademark talk box never become a mainstream effect? Well, it’s a one-trick-pony. A little goes a long way. It’s not something you want to overdo.

People say, ‘Oh, you’re this legend...’ What? No, I’m a regular guy. I’m not big on being put on a pedestal

"It was a fad, but when I use it today I still get the same effect from the people. It’s funny, it’s comedic. It’s not meant to be serious. I mean, how can that sound be serious?”

You’ve never taken yourself too seriously, though, have you?

“You know, making fun of myself, that’s my humor. People say, ‘Oh, you’re this legend...’ What? No, I’m a regular guy. I’m not big on being put on a pedestal. I never felt comfortable with that. I just enjoy playing guitar and seeing the smiles on people’s faces. That’s how I’m still able to do the hits - the ‘chestnuts’, shall we call them? - from years ago.

"Because I see the enjoyment in the audience. They just lap it up. It’s something that reminds them of a particular time, a particular person. Music turns on our memory.”

Did you enjoy the adulation heaped on you during that Comes Alive! period?

“I mean, there’s nothing like the feeling that everybody knows who you are, overnight, it seems. For the first three weeks, I had a big head. But after that, it gets difficult to do things when wherever you go you’re chased. But all that dies down.

"Now I live in Nashville and there are so many famous people here. Y’know, The Black Keys live here. Jack White. John Oates. And the great thing about here is everyone’s very respectful of everybody, because they know you’re going to run into Keith Urban one day in a Starbucks. It happens.”

Are there any periods of your career that you’re not so proud of?

When I did the last record for A&M, The Art Of Control [1982] - I had no control. So it’s quite ironic that I called it that

“The early '80s were not a great period for me. Because I’d had the car wreck in ’78, and everything sort of came to a screeching halt - literally. I started taking stock and that’s when I realized I was being screwed financially.

"When I did the last record for A&M, The Art Of Control [1982] - I had no control. So it’s quite ironic that I called it that. It’s one of my least favorite records, because I’m fastidious about sound and I just remember not caring how it was mixed.

"So I knew there was something terribly wrong. I think I just needed to not record that album, go away for a couple of years, regenerate and work out - where was I?

"I was very lucky to get back on an upward curve in the last 10 years. I think it was the Grammy for Fingerprints [awarded in 2007] that put the foot on the accelerator and made people more aware of me again. And it was for playing guitar, not singing. So that felt really special.”

The touring may stop, then, but what’s next for you?

“We’ve done three-and-a-half albums. We’ve done two blues albums. We released All Blues [2019] and there’s another one in the can; I don’t know when that’s coming out.

"We just finished an instrumental album of covers. Then there’s the solo record that we just started. There are some introverted lyrics about where I am, definitely. There may be some frustration on there, probably.

"But I don’t think it’s angry. There’s gratitude. I think it’s thankful. If you think about it, from when I was 16 in The Herd, until now - I mean, it’s been up and down, but it’s been a lengthy career. I have to be thankful for the incredible time I’ve had.”

Henry Yates is a freelance journalist who has written about music for titles including The Guardian, Telegraph, NME, Classic Rock, Guitarist, Total Guitar and Metal Hammer. He is the author of Walter Trout's official biography, Rescued From Reality, a talking head on Times Radio and an interviewer who has spoken to Brian May, Jimmy Page, Ozzy Osbourne, Ronnie Wood, Dave Grohl and many more. As a guitarist with three decades' experience, he mostly plays a Fender Telecaster and Gibson Les Paul.