“When I played Here I Go Again to Jon Lord he had a certain look in his eye. He said, ‘You’re a clever little sod, aren’t you?’”: Remembering Bernie Marsden, 1951-2023

The Whitesnake co-founder and lifelong bluesman left us on 24 August. Guitarist remembers an all-time-great player, writer, collaborator, collector, mentor and friend

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

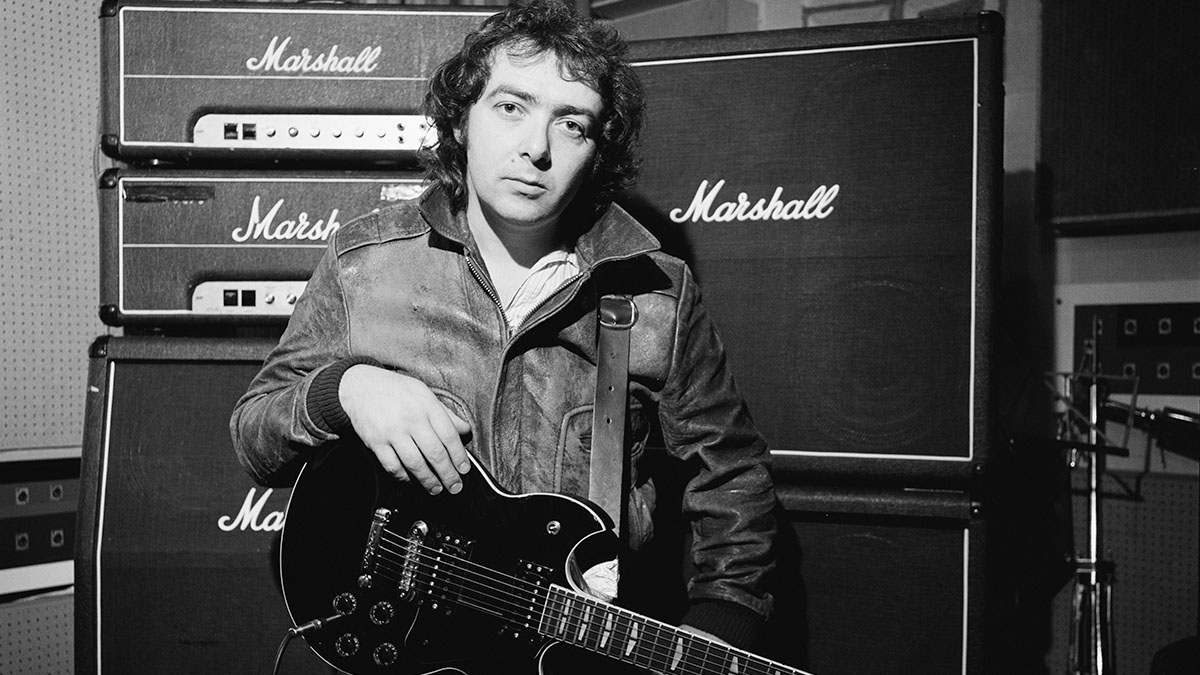

To the uninitiated, Bernie Marsden might have been easy to miss. In an industry of leather, motorbikes and top hats – and from a generation where ‘lead guitarist’ was shorthand for ‘show-off’ – the man once dubbed ‘British blues-rock’s secret weapon’ had the unstarry, affable, anecdote-ready demeanour of a pub regular.

But as the guitar community well knows, there was much more to Marsden, who died at the age of 72 as this issue went to press. The myriad reasons to toast the great journeyman’s final flight span from the anthems he wrote (which included Whitesnake’s Here I Go Again) through to the young musicians he mentored, the sweetness of his touch and the treasures of his superb vintage guitar collection.

Perhaps above all, among the pan-generational cohort of Guitarist journalists, we will miss a marvellous storyteller who often felt more like a friend than an interviewee – and whose generosity even extended to letting us play his fabled ‘Beast’ 1959 Gibson Les Paul Standard.

Born in Buckingham on 7 May, 1951, Marsden caught a glimpse of the world he wanted to occupy, at a young age: “People would take me to pubs when I was 14 because there was a band playing. Once I’d had a taste, that was it”. And then Clapton did the rest. Bernie shared that the Yardbirds and Bluesbreakers ace was “the first guitar player I really adored, because I was old enough to relate to it”.

But it was perhaps Peter Green’s Fleetwood Mac that made the defining impression, Marsden following his future friend’s live itinerary across the UK and later recalling in Guitarist that he was incandescent when Green recruited the 19-year-old Danny Kirwan: “How dare they get a guitar player the same age as me?”

Coming up in the early ’70s, Marsden made his own mark, though his career would prove a slower burn than Kirwan’s precocious rise (and fall). Early outfit Skinny Cat was an invaluable apprenticeship that went nowhere, and while Marsden hoped that moving to London in 1972 after passing an audition for UFO would “be like the cover of a Beatles EP, with everyone jumping in the air”, what briefly seemed like his big break crumbled into onstage fist-fights and a sour exit.

The guitarist moved on, repeatedly. He was variously spotted in Glenn Cornick’s Wild Turkey, Cozy Powell’s Hammer, and Hertfordshire rockers Babe Ruth. He filled the gaps with session work and reflected on his higher-profile stint in Paice Ashton Lord as “a flash in the pan, but one of the best things I’ve ever done”. He might even have auditioned for Bad Company, had housemate Mick Ralphs not been first in line for the gig.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Next, meeting singer and fellow blues fanatic David Coverdale at a Munich studio led to the partnership in Whitesnake that many fans consider to be the band’s best period.

Let off the leash creatively for the first time, Marsden – always a disciple of The Beatles’ pop smarts – began writing hooks for the ages on the Beast LP he had bought for £600 in ’74 and played on every Whitesnake record. “When I played Here I Go Again to Jon Lord he had a certain look in his eye,” Marsden told Rob Hughes. “He said, ‘You’re a clever little sod, aren’t you?’”

True to form, Marsden would be long gone by the time a reboot of Here I Go Again topped the US chart in 1987, and “only started to see royalties after taking the company to court many years later”.

Post-Whitesnake, the 30-something guitarist worried he was washed up, but his later period heralded some of his most soulful playing, whether in bands like Alaska, across his prolific solo blues career (his work ethic sometimes stretching to two studio albums in a single year) or as a foil to such luminaries as Ringo Starr, Gary Moore, Joe Bonamassa and Robert Plant.

With Marsden also latterly serving as a guiding light to younger players such as Laurence Jones, he often seemed like the glue that held the blues-rock scene together, a figure so omnipresent you sometimes wondered if he had a team of doppelgängers (this writer once found him in Walter Trout’s dressing room, debating whether to step in on bass after the US bluesman’s own four-stringer went AWOL).

Decades earlier, as a teenage gunslinger, Marsden had teased his mother when she worried her would-be-musician son was headed for a wayward life of bacchanals (“I said, ‘That’s what I want to do this for!’”).

In truth, the boundless joy of making music with those who felt the same way was reward enough for this most modest of guitar heroes. “I suppose I am proud of what has gone on,” Marsden wrote on his website. “After all, I only ever wanted to play the guitar for a living.”

Henry Yates is a freelance journalist who has written about music for titles including The Guardian, Telegraph, NME, Classic Rock, Guitarist, Total Guitar and Metal Hammer. He is the author of Walter Trout's official biography, Rescued From Reality, a talking head on Times Radio and an interviewer who has spoken to Brian May, Jimmy Page, Ozzy Osbourne, Ronnie Wood, Dave Grohl and many more. As a guitarist with three decades' experience, he mostly plays a Fender Telecaster and Gibson Les Paul.