'Scuse me while I hit this guy: Why Jimi Hendrix punched Television's Richard Lloyd – and why he didn’t mind

"I didn’t care that he hit me. He gave me something that I’ve carried to this day. It was a gift." In 1969, Jimi Hendrix slugged Richard Lloyd. 40 years later, Lloyd punched back with a hard-hitting tribute album to Mr. Purple Haze himself...

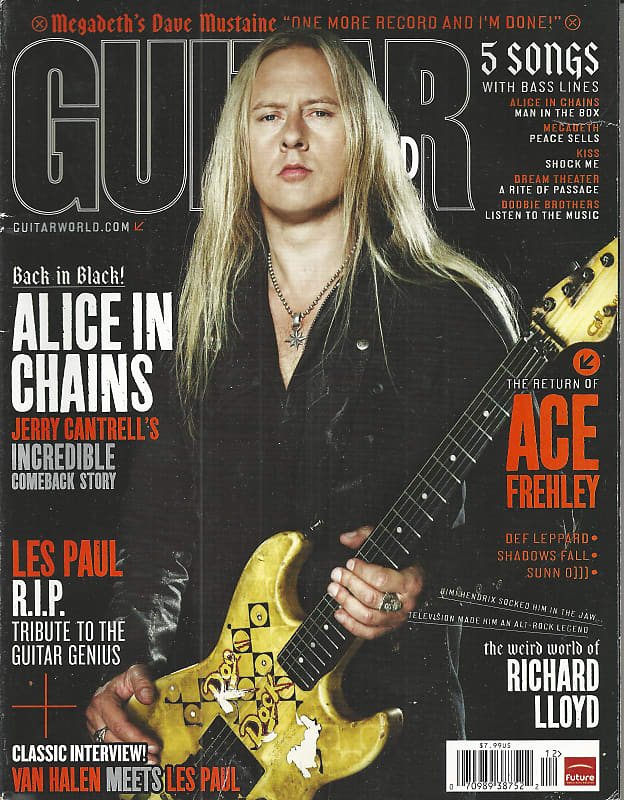

This article was originally published in Guitar World magazine, December 2009.

Somewhere around Black River Falls on I-94, Richard Lloyd pulled a large yellow onion out of his shoulder bag and started eating it like an apple.

“What the fuck are you doing?” I said.

“This is going to cure my laryngitis,” Richard said, spraying little bits of onion into the air through the gaps in his teeth. Onion juice dribbled down his chin.

“No, it isn’t,” I said. “The doctor told you the only thing that would help your voice was not talking.”

“Onions are anti-viral,” Richard said, continuing to munch and spray. The four of us—me, Richard, drummer Billy Ficca and bassist Keith Hartel—were riding in a Honda compact SUV. Even with the clubs furnishing the “backline” (bass amp and most of the drum kit), the car was dangerously overloaded, with two Stratocasters, two Precision basses, an ancient Supro Thunderbolt amplifier, Billy’s snare and cymbals and kick-drum pedal, all our bags, souvenirs that Richard bought in every truck stop, half-consumed bottles of prescription and nonprescription medicine that Richard bought in every drug store, half-consumed bottles of herbal elixirs that Richard bought in every New Age emporium, and a boggling array of books on occult weirdness, brain science and the sexual habits of tribal peoples around the world.

So shit was piled up to the ceiling in back, shit was piled up to the shoulder in the backseat between me and Billy, and shit was piled up to the elbow in the front seat between Keith, who was driving, and Richard, who was being Richard, in the shotgun seat.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“I have a virus,” Richard continued, as he turned 180 degrees and rested his chin on the top of his seat, fixing his unwavering eyes on mine, which were about 20 inches away. “It has nothing to do with talking. I had four years of medical school, so I know.”

I briefly considered yelling at him, as I had considered yelling at him many times during our tour of small clubs that had taken us down the East Coast, across the South and up the Midwest. It had already been a really long day, with Richard waking up at 6:00 a.m., after a late show in Minneapolis, and demanding medical treatment for his throat, which was ravaged both by singing every night and by his habit of talking relentlessly for 18 to 20 hours every day. So I—the embedded journalist and T-shirt seller and designated babysitter—took him over to the Hennepin County Medical Center, where we spent five hours dealing with security guards, clerks, aides, nurses and doctors, all of whom heard Richard insist that he needed a shot of cortisone in his vocal cords and they couldn’t fool with him because he had four years of medical school, which any moron could tell he didn’t.

I was hoping that someone would notice he was barking mad and put him in a rubber room for a month so he could get his meds adjusted. Instead we got a prescription for lozenges, which Richard threw in the doctor’s face. I then began hoping that someone other than me would beat the crap out of him and put him back in the hospital. Indeed, Richard was so irritating as he tried to convince people to stare at the sun with him on the sidewalk outside the hospital that a couple of guys began to square off with unmistakable violence in their eyes. But it didn’t quite happen. And we drove down I-94, where I decided to respond to the onion in the manner of Billy and Keith and just stare out the window with a clenched jaw and watering eyes.

After a few minutes of not provoking further argument with me, Richard got bored and turned back around and began sticking needles in his head. Acupuncture needles. Lots of them. In his scalp. In his face. In his ears. And all the while talking, talking, talking about his theories of oriental medicine, and how the needles were going to fix his voice. He was rasping so bad that I thought we might have to cancel the show that night. Blood was pouring down his face in little rivulets from the needles.

“Richard, I’ll bet you $20 you can’t shut up for 20 minutes,” I said.

“You’re on,” said Richard, who lost the bet in under 30 seconds.

“Double or nothing for another 20 minutes,” I said.

After maybe two minutes of silence, Richard was bugging. He couldn’t talk with $40 on the line, but he couldn’t just sit there either. So he rolled down the window and stood up, extending his entire upper body out the window where he waved frantically and meaninglessly at all the passing cars. The wind blew out most of the onion mist, even if I hadn’t quite engineered the moment of silence I was hoping for. And it was thus that we drove on to the Best Western Inn on the Park, a venerable old hotel across from the State Capitol Building in Madison, Wisconsin.

“Richard,” I said, “you’re not going to check in like that, are you?”

The guy had dried blood all over his face. Most of the needles were still stuck in his head. He was wearing parachute pants that he’d been wearing every day for seven weeks. His hair, dyed a reddish shade of brown unseen since Ronald Reagan left the White House, was hanging in asymmetric winding wisps to the left.

“You’ll see,” said Richard.

“You know the weird part about that onion?” Billy said as we sat on a couch in the lobby watching Richard approach the front desk. “It actually improved the smell in the car. It got rid of that horrible tobacco stink.”

It was true. Richard had been ingesting colossal amounts of tobacco in various forms: unfiltered cigarettes that he rolled himself, corncob pipes, chewing tobacco and snuff. If anyone objected, he claimed that he, like the Native Americans, was using it for religious purposes. The snuff was the worst. It looked like feces mixed with lawn clippings, and he’d stick globs of it up his nose, and then blow florescent brown puddles of snot into a Kleenex. So, yes, the onion was an improvement on the normal miasma of rancid nicotine in the car.

“I can’t believe it,” I said. “He looks like Leatherface. He looks like he’s going to cut up teenagers with machine tools. And they’re going to let him check in.” The two girls behind the front desk were laughing at his jokes, completely charmed.

“They want the money,” Keith said. “It’s a bad economy.”

And about three hours later, Richard walked across Carroll Street from the hotel to the Frequency, took the stage with his Stratocaster and delivered two hours of shit-hot rock and roll to the loudly appreciative Cheeseheads that had packed the joint. True, it was a small club with an official capacity of 99, but compared to any other band on the planet in any other venue that night, the performance was still up there in the number-one percentile of shit-hottedness.

Great songs from Television (“Friction,” “See No Evil”) and all the different periods of Richard’s solo career (“Field of Fire,” “Wicked Son”) interspersed with five or six monster Hendrix covers. So for about the millionth time in three weeks on the road, Richard completely flummoxed me. I would have sworn on a Bible he was going to suck in Madison. Just two nights before in Omaha he’d spent most the show cursing the audience and lying to them about why he was two hours late to the gig. It may have been the most appalling concert I ever saw. Compelling, too. Like a car wreck. But Madison: brilliant and compelling. I mean, who is this guy?

Fuck if I know. In my entire life, I’ve met one person, a paranoid schizophrenic, who was crazier than Richard Lloyd. And I never encountered anyone who was a bigger pain in the ass. He is also one of the best electric guitar players I ever heard, and he’s one of the smartest people I ever talked to. As readers of this magazine know from his Alchemical Guitarist column [Lloyd did a regular column for Guitar World, later collected in DVD form – some episodes are on our YouTube channel], he can teach as well as play. When he’s focused, he can explain scales and harmony and the circle of fifths so that almost any non-bonehead can figure it out. He has all kinds of interesting mystical theories about the physics of it all. He’s writing a book called Alchemical Guitar for Alfred, and I have no doubt I’ll learn lots of useful, fascinating stuff.

He has interesting theories about almost everything.

Richard’s most immediate big project is the anomalously named The Jamie Neverts Story, an album of Jimi Hendrix covers to be released in September. The obvious question here is “Why?” Hendrix is one of the most influential guitarists of all time. Anyone who cares about electric guitar already knows his stuff intimately. It’s part of the canon. Nobody can improve it. And Richard has his own vibrant musical imagination, always erupting with new lyrics and riffs. He doesn’t need to cover anybody.

For an explanation, we shall back up. Richard Lloyd was born in 1951 in Pittsburgh, when everything was still covered with soot from the steel mills. His parents married and divorced young, and he spent his early years in the care of his grandparents. In early grade school, he moved to New York to join his mother, an aspiring actress, and stepfather, a film editor. The family moved from neighborhood to neighborhood as their fortunes improved, and ended up in Greenwich Village just in time for the Sixties to flower. Pretty much everything that was cool about the counterculture was within walking distance, and Richard had the stratospheric IQ and sense of adventure to ingest it all.

One afternoon, probably in early 1968, Richard and his buddies pooled their money to buy some hash. While they were waiting for the delivery, the phone rang, but it wasn’t the guy with the hash; it was some black kid from Brooklyn that a few of them knew, though he was unknown to Richard at the time. His name was Velvert Turner, and he preposterously claimed to know Jimi Hendrix. Velvert asked if he could come up, and while the hash investors waited for him, they agreed to make fun of Velvert when he arrived, because no mere teenager could know Jimi Hendrix.

“About 10 minutes later, the doorbell rang,” says Richard, sitting in his Manhattan rehearsal space about a month after the aforementioned tour. He is wearing a Michael Jackson–type fedora, massive amounts of bling, and the same parachute pants that he’s been wearing every day for months. “When Velvert came in, I knew to an absolute degree of certainty that he knew Jimi Hendrix. He carried something with him that only belonged to Jimi.”

Richard starts crying at the memory. “And they laughed at him. And I knew they were wrong. I was like, ‘Why are you cats treating him so poorly? Why can’t he know Jimi Hendrix? Jimi doesn’t live on Mars. He has to know somebody.’ ”

Velvert picked up the phone, dialed the Warwick Hotel, asked for a name nobody had heard of and explained to the boys that Jimi had to travel under assumed names. The phone rang and rang, and Velvert was near tears. He passed the phone from guy to guy so they could at least hear it wasn’t a dial tone.

“When it was my turn to listen, it rang one and a half times,” Richard says. “Somebody picked up, and this sleepy voice said, ‘Hey man, what’s up? Who is this?’ He must have been really asleep, ’cause it rang about 14 times. I couldn’t say, ‘Hi Jimi, it’s Richard Lloyd,’ so I said, ‘It’s Velvert,’ and handed off the phone. Velvert took it and went into the kitchen to talk, and everybody else was like, ‘Was that really Jimi Hendrix? How could you tell?’ Well, I could tell. No one had that voice except that man.”

Velvert returned from the kitchen transformed from an object of scorn to one of worship. He announced that he was on the guest list for Jimi’s concert that night and asked would anyone care to accompany him? The room went crazy, and Velvert took his time, choosing the quiet kid in the corner who refused to beg. That kid was Richard Lloyd, and they indeed saw Hendrix that night.

Richard recalls, “The first song we heard was ‘Are You Experienced,’ and I was agog. I didn’t think anyone could do that song live. The films we see of him now don’t do him justice. They were all made late in his career when he was tired and crushed by his business manager. He signed a lot of contracts he shouldn’t have. But that night, I was agog. It was like seeing God.”

It turned out that Velvert didn’t just know Jimi—he was his protégé, confidante and guitar student. Richard quickly became Velvert’s best friend, and the two vowed to carry their own Stratocasters almost everywhere almost all the time, even to school. They vowed never to pay for a concert and used their considerable social skills and growing connections to sneak in or charm their way onto guest lists. Most important, whenever Jimi gave Velvert a guitar lesson, he would teach Richard everything Jimi had taught him, so Richard was a second-hand student of Hendrix.

“Velvert showed me some other things as well,” Richard says. “Magic spells that Jimi had taught him and that Jimi had learned from his grandmother. He was one-eighth Cherokee, and he knew real voodoo. Black magic. I haven’t done them myself, because I think they backfired on Jimi. It’s like the stories about genies. They grant three wishes, and the third wish is always to take back the first two, because of unforeseen consequences.”

In November 1969, Jimi played a small club in Greenwich Village called Salvation. It was supposed to be a warm-up gig for a long tour, and an early birthday party for Jimi. It was billed as the Black Roman Orgy. The sound system was crap, and Jimi gave up after a few songs, returning to his table where Richard had somehow wangled a seat. As the evening wore on and the sundry guests got up to go to the bathroom, Richard found himself sitting right next to Jimi, who was in a deep state of melancholy, complaining that he was trapped, being forced to perform like a circus act, and that he wanted to explore new musical terrain but “they” wouldn’t let him.

Richard decided to give him a pep talk, tell him how much his music meant, that he should do what he wanted, because he was Jimi Hendrix. Jimi turned around and slugged Richard three times. Richard then hid out in the club for a while on the theory that he didn’t want to get slugged some more by Jimi’s security guards. After half an hour or so, Richard decided it might be safe to exit. Outside, Jimi was waiting for him in one of his Corvettes in the parking lot.

“He called me over and asked for my hands,” Richard says. “He apologized and began weeping on them. My hands were wet with his tears. I kept telling him it was okay, and finally he rolled up his window and drove off. Velvert later explained to me that Jimi hated compliments, thought they were patronizing. I didn’t understand that he was being tortured by criminals. But I didn’t care that he hit me. He gave me something that I’ve carried to this day. It was a gift. And that’s why I had to make this album. I owe Jimi. And I owe Velvert.”

Why not call it the Jimi and Velvert Story? “‘Jamie Neverts’ was what Velvert and I called Jimi when we didn’t want any of the other kids to know who we were talking about.”

TheJamie Neverts Story is a great album. All the guitars were recorded through Richard’s Supro Thunderbolt, which is turned up to 10 for a taste of distortion, though most of the tones are pretty clean. You can hear the lyricism that sometimes gets buried in the guitar wash on Jimi’s own albums. There are minimal overdubs, just Jimi’s slashing style married with Richard’s slashing style. I’ve always had a thing for “I Don’t Live Today” (“That was Jimi singing on behalf of Native Americans”), and Richard rips it, but the best moment may be the quietest—“Castles Made of Sand,” about the temporary nature of everything and the death of dreams. Richard could make you cry when he played it during the tour, if he wasn’t screaming obscenities at the audience. That made me cry too, but in a different way.

“There’s no fuzz box, no wah-wah, no Octavia—none of the things that people buy to sound like Hendrix,” Richard says. “It’s just not fresh anymore. Psychedelia has been around for a long time. I wanted to emphasize the songs themselves, especially the ones on the first two albums where Chaz Chandler [bassist for the Animals and Jimi’s first manager] had an influence. I loved what Chaz did, sitting with Jimi while he jammed and telling him what lick was the chorus and what lick was the verse. All those songs, you’ll notice, are short. That was Chaz. I didn’t want the big guitar hero songs like “Voodoo Chile (Slight Return).” And I didn’t want the songs that Jimi came to hate, like “Foxy Lady, because it made him look like a clown.

"What I wanted to convey was clarity, melody and the songwriting skills that emerged when Chaz and Jimi were together. Jimi’s lyrics are incredible, but people don’t notice because the guitar was so revolutionary.”

After Jimi died in 1970, Velvert signed a record contract with Family, a division of Paramount, and recorded an album in 1972 as the Velvert Turner Group. He was marketed as the new Jimi, nobody cared, and he crashed and burned in the sea of Seventies rock decadence, emerging sober after some years and becoming a drug counselor. He died in 2000 of hepatitis C.

Richard Lloyd subsequently was institutionalized a couple times for mental problems and founded Television, which released its classic debut album, Marquee Moon, in 1977. It has been continuously in print for ever since and is near the top of many lists of best albums ever. He was crucial to the early success of CBGB, helping to book the now-defunct club in its glory years. His solo albums are pretty amazing too, especially 2001’s Field of Fire and 2007’s The Radiant Monkey. Like many people with bipolar disorder, he pissed away many chances at success by self-medicating with drugs and alcohol. He now limits himself to drugs prescribed by his psychiatrist.

After Madison, we went to Chicago, where Richard threw a colossal tantrum onstage and in the dressing room afterward. In Detroit he threw an even worse tantrum in the car after the gig, causing us to swerve all over the freeway. He continued the tantrum at our hotel, and the front desk clerk called the police to evict him. Billy, Keith and I rented a car and drove back to New York the next day. Richard did the last four dates—Cleveland, Dayton, Rochester and Boston—by himself. Somebody beat the crap out of him in Boston after the show and sent him to the hospital with a black eye. Somebody beat the crap out of him again in New York a week later and sent him to the hospital with another black eye. Those of us who know Richard spent a lot of time on the phone trying to figure out what the hell to do.

“I see a freight train of success heading toward me, and I’m going to let it hit me,” says Richard, who plans to tour again in the fall with another band. “Every other time I’ve ducked or jumped to the side. I didn’t allow for personal success because I was loyal to Television. No more. I wouldn’t be doing this if I weren’t at the height of my personal powers, but I am. Whatever comes my way now is mine.”

This article was originally published in Guitar World magazine, December 2009.

Charles M. Young was the first American writer to cover the Sex Pistols, in a 1977 article for Rolling Stone magazine. An incredible writer, he also went on to write for Musician magazine, and the music section of Playboy. He died in 2014 from a brain tumor at the age of 63.