Richie Faulkner: “Getting the guitar back in my hands was what I needed to do to get back on track – to give me the strength to keep going”

On September 26, 2021, while onstage with Judas Priest, Faulkner came incredibly close to dying. Miraculously, he’s here to tell the tale – and what a tale it is...

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

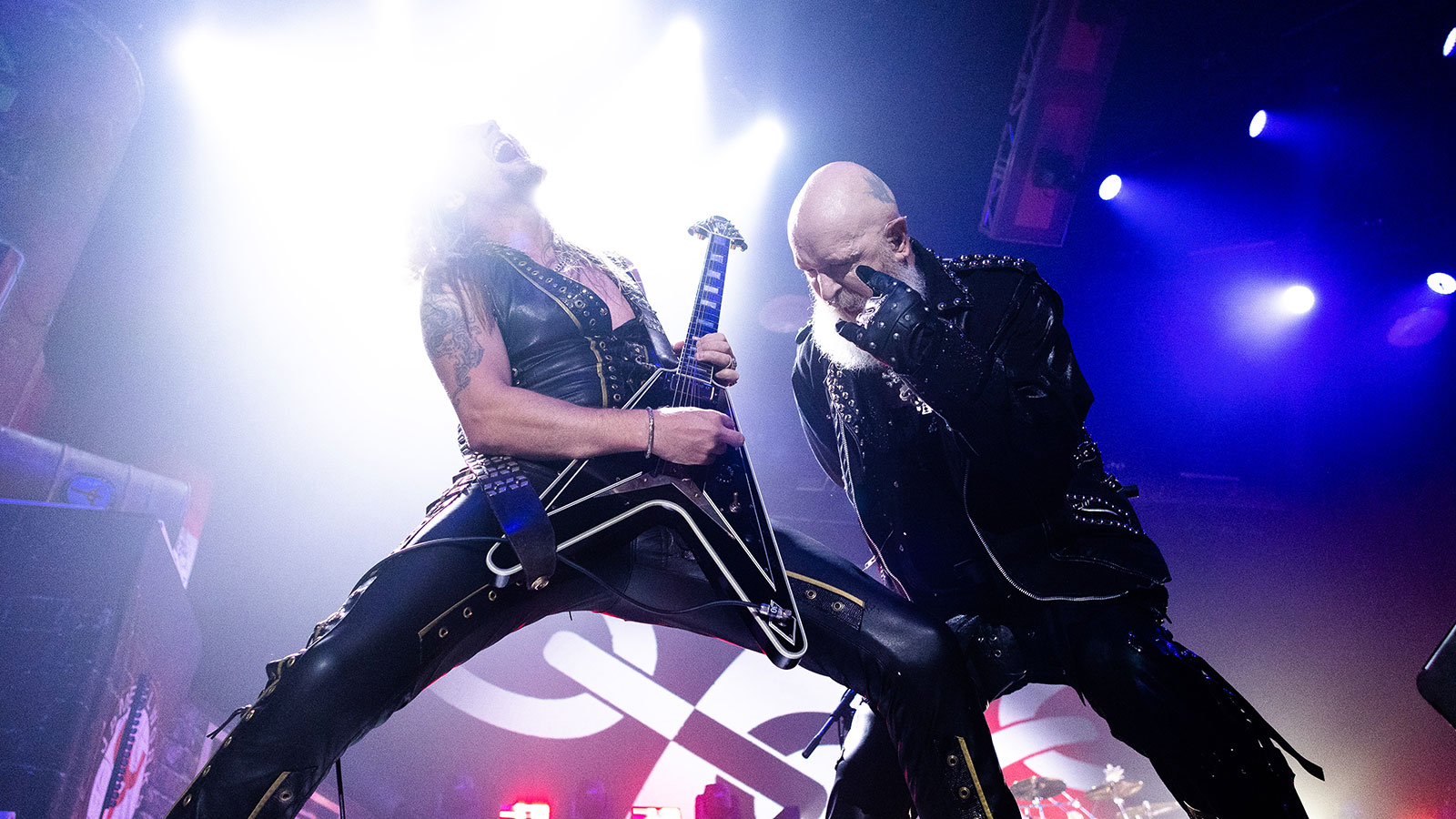

For Judas Priest guitarist Richie Faulkner, September 26, 2021, started out like any other gig day. The band was scheduled to play support to Metallica on the fourth and final night of the Louder Than Life Festival in Louisville, Kentucky. Faulkner was a little tired, but after two and a half weeks on tour, that was hardly unusual.

He poured himself a vodka and Red Bull and downed it. Combined with the adrenaline of playing to a sold-out crowd, he soon perked up and was excited to take the stage dressed in trademark studded black leather vest and black leather pants, and wielding a Gibson Flying V.

Judas Priest opened with One Shot at Glory from 1990’s Painkiller, then launched into Lightning Strike from 2018’s Firepower. By the third song, the 1982 anthem You’ve Got Another Thing Comin’, they were locked in and celebrating career-spanning songs on their long-delayed (due to Covid) 50th Anniversary tour.

The hour-long set flew by, and as Judas Priest played the last song of the night, the hyper-charged Painkiller, Faulkner continued rocking out, shaking his leonine locks and alternating between joyful smiles and metal grimaces.

I’m feeling good. I’m feeling strong. I know I’m incredibly fortunate to be here. I know that. But it’s still hard to believe it really happened

Halfway through the song, the grimaces became real. Faulkner felt his chest tighten. Moderate pain and pressure swept through his midsection. He felt disoriented and short of breath. Even so, he was driven by devotion and managed to play a dextrous whammy bar-enhanced solo and even raised his guitar to the sky. As vocalist Rob Halford delivered the final vocal salvo, Faulkner exited the stage and collapsed into a chair.

“I needed to finish the song, but I had the presence of mind to come back from the edge of the stage just in case I passed out from fatigue,” Faulkner says in a Zoom interview six months after the Louisville show.

“Luckily, Metallica was headlining that night or we would have played a full set and I probably would have dropped dead onstage.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Paramedics urged Faulkner to go to the hospital. But the guitarist felt constricted in his tight leather and wanted to remove his stage clothes before figuring out what to do next.

“If I had known my heart had split open and I was bleeding into my chest cavity, I might have handled it a bit differently. But I had no idea,” Faulkner says. “I got my jeans and T-shirt on. I didn’t think it was anything really serious and I didn’t want to make a fuss. I probably would have kept going if we did an encore.”

When he got back to the medics and his girlfriend Mariah Lynch (daughter of Dokken star George Lynch), Faulkner said he thought he was just exhausted and instead of going to the hospital, he wanted to drive two and a half hours back home to his place near Nashville.

If I had known my heart had split open and I was bleeding into my chest cavity, I might have handled it a bit differently. But I had no idea

“The original plan before the show was to drive home and have a few days off at the house to spend with our new baby,” Faulkner says. “Then I was going to fly to Denver to meet the band and carry on with the tour. I figured I could still do that. I’d been healthy before the show, so I was like, ‘Obviously, it’s not a big deal. Let’s just get in the car and go back home. It’s going to be okay.’ There’s no question I would have died in the car on the way back home if I even made it to the car.”

At the insistence of the medics, Lynch convinced Faulkner to get into a waiting ambulance. As it turned out, his aorta couldn’t have exploded in a better location. The Highland Festival Grounds at the Kentucky Expo Center is five miles from the Rudd Heart and Lung Center at UofL Health– Jewish Hospital, which has one of the best and most well-equipped cardiac units in the country.

With six months of hindsight, the guitarist fully recognizes that he nearly lost everything on September 26 and now he has more appreciation for his family, friends and band. At the same time, he says it seems like the incident in Louisville happened so long ago it has little bearing on his life today.

“It’s so weird because I’m feeling good. I’m feeling strong,” he says. “It feels like a lifetime ago when I was onstage in Kentucky dancing with the Reaper. I know I’m incredibly fortunate to be here. I know that. But it’s still hard to believe it really happened.”

During a lengthy, revealing Zoom call, Faulkner talks about being completely blindsided and disoriented by his aortic dissection, the extent of damage to the arteries around his heart, how surgeons rebuilt him with powerful metal, and his post-op struggle to regain the strength and stamina he needed to tour again with Judas Priest.

He also addresses the announcement that the band was going to tour as a four-piece, the unique writing relationship Faulkner has with Glenn Tipton, the follow-up to Firepower, and plans to work on a side project beyond the realm of Priest.

Ironically, at 42, you are the youngest member of Judas Priest and your bandmates are elder statesmen. Yet, despite various illnesses and accidents some of the other guys have suffered since you joined, you’re the only one who has come so close to dying. Did you have any personal or family history of heart ailments?

“No, nothing. It came right out of the blue. I think there was high blood pressure pounding on the walls of my aorta, and over time it weakened the walls without anyone knowing. And then, finally, it just burst.”

That’s terrifying. Were there any warning signs?

“Not that I could tell. They say people who are having heart problems sometimes have backaches, but I’m 42 and I’ve been running around onstage forever. So my back has been hurting daily since I was about 35.

“In February 2020, I had a physical in England and the doctor checked my blood pressure and said it was a little high, but she said it was okay and there was nothing to worry about. The Kentucky show was in September the following year, and there was never any indication of any problem before I got halfway through Painkiller.”

What do you remember from the time you got into the ambulance?

“Everything was a whirlwind. You’re on a stretcher being walked down the corridor and you’ve been pumped full of adrenaline because you’re going under and you might not come out of it. And you have no idea what’s going on. Then, if you’re lucky, you wake up in a recovery room.”

I’m more metal now than ever. I like to joke that I’ve literally got a heart of metal

What did doctors do when you were on the operating table?

“They knew I needed open-heart surgery and thought they were going to have to do a four or five hour operation. So they opened me up and saw I had an aortic aneurysm [a ballooning of the aorta, the main artery that carries blood from the heart through the chest and torso].

“It had ballooned and ruptured [causing blood to flood through the tear with such force the inner and middle layers of the aorta split]. So it was a lot more severe than what they anticipated, and the procedure took them 11 hours. I had to have four blood transfusions.”

Were they confident they could fix the damage and stitch you back up?

“Honestly, they weren’t sure. Partway through, they had someone come out and tell my other half to call for my family to come to the hospital because they didn’t know if I was going to make it out.

“When my aorta dissected, the artery split all the way to my waist. And then there are the arteries that go up to your brain and it split and dissected all the way up there as well. So the whole thing just exploded. It’s really amazing they were able to bring me back.”

They think that maybe my adrenaline was so high because we were playing – so I can literally say the power of heavy metal kept me alive long enough to save my life

Did they fix everything?

“They repaired the rupture and the aneurysm. There was no heart attack to fix. My heart was completely fine. It was the aorta that burst, so they repaired it with a mechanical valve. And they repaired other parts of my heart with bits of metal since the dissection caused a lot of damage. I’m more metal now than ever. I like to joke that I’ve literally got a heart of metal.

“But I know how serious it was and I know I would have died if I didn’t have these miracle doctors. But they couldn’t repair everything. The bit [of artery] that goes down to my waist is still dissected. It’s just not life-threatening. Nothing’s going to happen in the short term.”

Why didn’t they repair that during the operation?

“They couldn’t keep me under anesthesia any longer. Otherwise, I might have suffered brain damage. So they had to stitch me up and now doctors keep an eye on it. If you monitor your heart rate and your blood pressure, it can scar over and you can be fine. But if it gets bigger over time, they can operate on it and fix it then.”

Considering your aorta split onstage and you were bleeding out, it’s amazing you were able to get to the hospital in time.

“One question I had for the doctors was how I was able to go on for so long, because, yeah, once these things rupture you’ve usually got minutes and you’re gone. They think that maybe my adrenaline was so high because we were playing and that my heart was pumping hard enough and fast enough to keep me going long enough to get pumped up with more adrenaline and keep me going to the hospital. So I can literally say the power of heavy metal kept me alive long enough to save my life. I was literally, possibly saved by metal.”

Do you remember waking up in the ICU?

“I opened my eyes and there were tubes sticking out of me everywhere. That was really weird. But I realized I was still here. I was in the ICU for four days and I made a gradual, day-by-day recovery.”

Can you explain the recovery process?

“I was in [the] hospital for 10 days, which they said was really good since a lot of people with my condition are there for a month. But it was hard. I had to stand up not long after they cut me open, and that wasn’t fun. They made me walk, and I couldn’t because your muscles atrophy and you’ve got no strength left in your legs or arms. I had to relearn how to walk.”

I’m relatively young for this kind of thing. I’m not a smoker, I’m not a big drinker. But at the end of it all, I’m the luckiest man in the world

“After a few days, you can do 10 steps with the walker and you’re exhausted. It’s awful but you’ve got to do all these things to gradually build up your strength. And you have all these breathing exercises as well because your lungs deflate when you’re lying down and you’ve got to do them to prevent pneumonia. That was the most painful because your chest cavity hurts like hell.

“You have a big scar up there that they sewed together and every time I breathed in, even a little bit, it hurt. For these lung exercises, I had to breathe as hard as I could. And then, hopefully, you don’t sneeze or cough, ’cause that’s just the end of the world.

Were you going stir crazy while you were in the hospital?

“I was determined to get out, but they obviously won’t let you go until they’re satisfied with your recovery. After 10 days, they said I could leave and I continued my recovery at home. I’m sure the combination of my stubbornness and determination helped me heal faster. And I think my youth was on my side.

“I’m relatively young for this kind of thing. I’m not a smoker, I’m not a big drinker. But at the end of it all, I’m the luckiest man in the world. Some people who have aortic dissection lose their arms or legs or they don’t make it. I’m the most fortunate person that’s ever lived. I’ll be on medication for the rest of my life, but that’s a small price to pay.

Did you have a guitar with you in the hospital or was playing again not even a concern at that point?

“I didn’t have a guitar and there’s no way I could have played it while I was in hospital. But one of the first things I worried about was whether I would still be able to play. When I woke up in the ICU I think one of my first questions was, “What’s happening with the tour and what are we going to do?”

What did they tell you?............

“They told me I was in the ICU and obviously the tour wasn’t still going on. It’s kind of funny that my first concern was about the tour, but I think a large part of anybody’s recovery is pushing yourself to get back to who you are. I wanted to recover for my family and my daughter. Getting back home and getting the guitar back in my hands was part of what I needed to do to get back on track and to give me the strength to keep going.”

How long did it take you after you got home to pick up a guitar again, and were you able to play right away?

“About four days after I got home, I tried to play. That was two weeks after it happened and that was hard. You want everything to be exactly the way it was, but you’ve been through this intense trauma. You don’t know if you’ve lost too much blood to your brain and if your fingers will ever be able to function like they did. I was determined but I was also worried.”

When was it clear you could play again?

“It took a little while. I’d work at it and sometimes it would get a little bit easier, and that made me feel a bit better. And sometimes I was tired or just not focused and it was hard and I got frustrated. But I kept going and it got to a point where it kept getting easier. That gave me this sense of accomplishment and kept me going because I realized there was a light at the end of the tunnel.”

Andy has been fantastic standing in, but I think we’ve never really thought about who is going to either replace Glenn

Have you had to change your lifestyle or diet since your brush with death?

“The good thing is my heart is fine. So the most important thing is to keep my blood thin enough to pass through the mechanical valve. I’ve had to cut out broccoli, Brussels sprouts, spinach – all leafy greens.

“But I can have meat, carrots, potatoes and ice cream. That works just fine for me. I have to watch my salt levels and keep an eye on my blood pressure and heart rate. And I’m on the blood thinner, Coumadin, which prevents blood clots. As long as the blood doesn’t get too thick and start to clot, they said I can even have a couple of drinks every now and again.”

Before the tour resumed, the band issued a statement that mentioned the 50th Anniversary shows would continue with you as the sole guitarist. That surprised a lot of people, including second guitarist Andy Sneap.

“Andy has been fantastic standing in, but I think we’ve never really thought about who is going to either replace Glenn, or who is going to be the permanent road guitarist. Obviously, Glenn is still in the band. But the question we were asking ourselves was, can we have a permanent stand-in or will we do something else?”

Was a tour without a second guitarist going to be a test for the latter?

“Well, Rob called me one day and he said, “Falcon, would you be able to handle all the guitars?” I think he had mentioned something like that on the socials a few days earlier. I said, 'Yes, I think so.' He said, 'It might be cool if we went to being a four-piece like we did in the beginning because then we wouldn’t be replacing Glenn. That might be the solution.'

“I said, 'Well, whatever you want to do, Boss. If that’s what everyone wants, I’m up for it.' I really thought it would have sounded great. We all did. I went out and bought four harmonizer pedals to try to build up the sound. We didn’t need any of them in the end.”

Were you surprised how fans reacted to the initial statement? Even Andy issued a statement suggesting he was surprised by the decision.

“It just shows how passionate people still are about Priest. If they didn’t care, we would’ve really been in trouble. But they cared an awful lot, and they expressed how they felt – and we listened. It was the only way to go. And, at the end of the day, I think Andy wants to be a part of it and wants to help out wherever he can.

“So he was disappointed but respectful of the original decision to tour as a four-piece. And he was happy when we changed our minds. He has always said he’s a big fan of the band and he’ll do whatever we need.”

Glenn’s challenges have affected him, but as long as you’ve got his creative spark and ideas, and he’s involved, that’s all you can ask for

Glenn said the band wrote some new material for the next album before Covid hit. Sadly, he has Parkinson’s and can’t play like he used to, but he can still write music. When you work together now, does he explain how he wants you to play a riff or a part? Or does he demonstrate what he wants by playing it as well as he can and then having you further develop it?

“Both, really. It depends if he’s having a good day or a bad day. He’s always got parts in his head and will try to communicate by telling me how to do it or showing me an example. Sometimes, he does stuff on his own and then presents the idea after he’s worked on it for a bit.

“If we’re doing something together he might say, 'Try this or try that.' Glenn’s challenges have affected him, but as long as you’ve got his creative spark and ideas, and he’s involved, that’s all you can ask for – that excitement from him and his input.”

Are you taking more of a writing role now with the band than you did on Firepower?

“I think it will be the same. Before the pandemic, me, Rob and Glenn did a session together and we got down some great ideas. But then during the shutdown, because of the separation, I think we’ve done more on our own. Usually we’re more collaborative. So it will be interesting to see how this one comes out because of all the individual ideas that have come up.”

When will you re-enter the studio?

“We’re still looking for a window to get together. We’ve got songs in demo stages so we’re off to a good start. There’s definitely enough material for a record – probably more than enough. Now we have to get them all to the next stage.”

Guitar runs in my daughter’s family. Grandpa is George Lynch so she loves guitar

Do you have more potential Priest riffs to bring to the table than you had when you started the album?

“Yeah, I’m always writing bits and pieces and putting stuff together. Sometimes they’re Priest-like and sometimes they’re not. It’s funny because sometimes you write stuff you think would never work in the band, but then you put it forward in a session and it becomes Priest.

“Glenn puts a little twist on and Rob adds his ideas and there you go. On Redeemer of Souls, Crossfire was something I didn’t think would work, but I showed it to the guys anyway and it became a pretty cool track.”

Despite the care you took with social distancing and immunizations, you caught Covid shortly before returning to the road for the 50th Anniversary tour. Were you in an immuno-compromised state because of your aortic dissection?

“I’ve been working on building a studio with a friend of mine. We were both isolating with our families and I had my immunization shots and my booster. But yeah, I somehow got Covid.

“I think I got the [Omicron] variety because it didn’t last too long. I didn’t lose my taste and smell, but I had a bad cough. I had one bad night and then three or four nights when I felt like I was getting rid of it. But we’ve got a 19-month-old baby in the house and we wanted to protect her. She got it, anyway, but she was fine.”

I worked on a solo project during the pandemic and we’re in talks at the moment with labels. I don’t want to give too much away...

Has your daughter shown a gift for music?

“Guitar runs in her family. Grandpa is George Lynch so she loves guitar. She loves Def Leppard’s Hysteria and now she loves Pyromania, so she has gone up a level further toward metal. She’s so much fun and she’s got an attitude on her.”

Do you and George get along well?

“He’s based in California so he comes over when he can, which is great. He’s great with the baby. George has always been there at the top of the guitarists I liked. I first got into Judas Priest, Iron Maiden and Metallica. Then there was Eddie Van Halen, Vai, Satriani and Paul Gilbert.

“But George had this unorthodox way of playing. Everyone else tried to be everyone else, but he had a weird way of playing that you could identify right away. When he comes around and plays, he’s still got a weird style that’s really unique and you can’t copy it.”

George had this unorthodox way of playing. Everyone else tried to be everyone else, but he had a weird way of playing that you could identify right away

Have you jammed with Grandpa George?

“We did a couple of live jams – the Instagram live thing. We thought we’d talk for a couple hours, but he loves guitar and gear. We talked all night. But we didn’t write anything together.”

Do you want to do a solo album?

“Yeah, but I’d like to do it more as a band thing. I wouldn’t want it to be called Richie Faulkner’s Rainbow. I worked on a project with a few people during the pandemic and we’re in talks at the moment with labels. I don’t want to give too much away, but when the pandemic hit I thought maybe it’s time to get a batch of songs and get them into shape and put them out.”

Will it be a metal album?

“It’s always hard to talk about your stuff without crawling up your own ass. I think it’s heavy, but it’s not as 'metal.' It’s a bit more bluesy. You can hear that it’s coming from a guitarist in Priest, but it’s enough of a departure to sound like something outside of the band. There’s some Hendrix references in there and stuff that’s a bit more groove-oriented.”

Has being on tour again and planning for future albums put you in a better mindframe than you were in before the aortic dissection?

I have more of an awareness now of what can happen to anyone at any time. That’s scary, but it puts things in perspective and makes you appreciate what you have.

“Yes and no. I want to just be myself and do what I do and play with Priest and play guitar and be a dad. But I have more of an awareness now of what can happen to anyone at any time. That’s scary, but it puts things in perspective and makes you appreciate what you have.

“It was such an emotional moment when I put my foot back on the stage in Peoria, Illinois, for the first date I played after my incident. To get up there and hear the fans cheering and showing their appreciation was like a celebration of everything I’m so lucky to still be involved with. So I know I have a lot to be thankful for.”

- Reflections – 50 Heavy Metal Years of Music is out now via Legacy Recordings.

Jon is an author, journalist, and podcaster who recently wrote and hosted the first 12-episode season of the acclaimed Backstaged: The Devil in Metal, an exclusive from Diversion Podcasts/iHeart. He is also the primary author of the popular Louder Than Hell: The Definitive Oral History of Metal and the sole author of Raising Hell: Backstage Tales From the Lives of Metal Legends. In addition, he co-wrote I'm the Man: The Story of That Guy From Anthrax (with Scott Ian), Ministry: The Lost Gospels According to Al Jourgensen (with Al Jourgensen), and My Riot: Agnostic Front, Grit, Guts & Glory (with Roger Miret). Wiederhorn has worked on staff as an associate editor for Rolling Stone, Executive Editor of Guitar Magazine, and senior writer for MTV News. His work has also appeared in Spin, Entertainment Weekly, Yahoo.com, Revolver, Inked, Loudwire.com and other publications and websites.