“Playing with Bob Dylan was like entering The Twilight Zone of music. You thought, ‘They’re going to wake me up tomorrow because all of this is impossible’”: Robbie Robertson reflects on his remarkable career and the end of the Band

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In honor of the late Robbie Robertson, who passed away on August 9 2023, we are republishing his final Guitar World interview. This feature was originally published in Guitar World’s February 2020 issue, which went on sale December 31 2019.

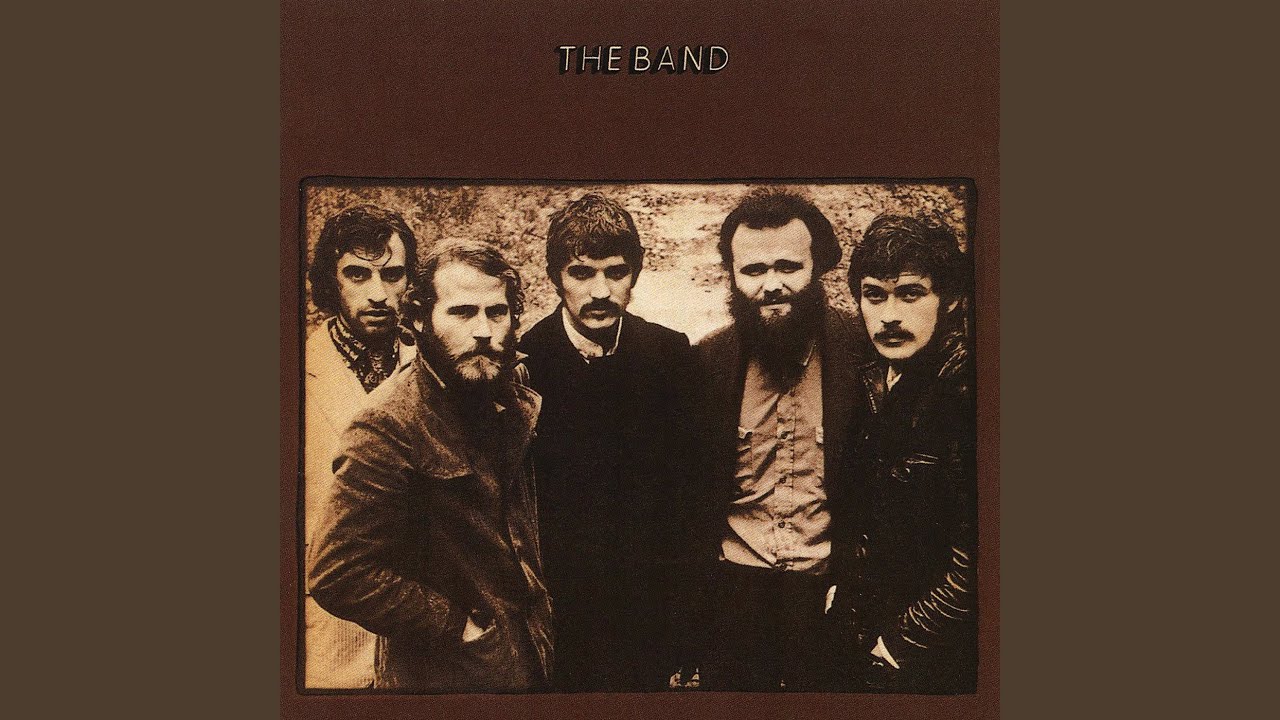

The Band’s 1968 debut album, Music from Big Pink, was such a bolt of originality – creating what came to be known as Americana – that it reverberated throughout the rock world. Eric Clapton said he broke up Cream immediately after hearing it and even trekked to Woodstock, New York, to meet its makers, as did George Harrison.

“I knew the album was good and different, but I was surprised by the impact on people like Clapton and the Beatles,” guitarist and songwriter Robbie Robertson says, 51 years later. “We were together for six or seven years before we recorded our debut, honing our skills, learning our craft and gathering music – gospel, blues, mountain music, sacred harp singing, Anglican hymns.

We were putting everything in our big pot of gumbo, and when we made a record sounding like that, all these guys asked, ‘Where the hell did this come from?’ That’s what happens when you really go out in search of a sound.

“We were bringing a musicality that wasn’t already there. So there was a freshness and newness to it. And it opened up some people’s ears. They really thought it was coming from another world – and it was, in a way.”

Robertson is Canadian, as were all of his Band-mates, with the notable exception of the Arkansas native Levon Helm, the drummer/singer who was also a big brother and musical guidepost for the rest of the group.

The Band first came together backing rockabilly singer Ronnie Hawkins, did an intensive internship as Bob Dylan’s first electric band in 1965-66, then emerged as a singular artistic voice, creating rock laced with country, blues and other folk music.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

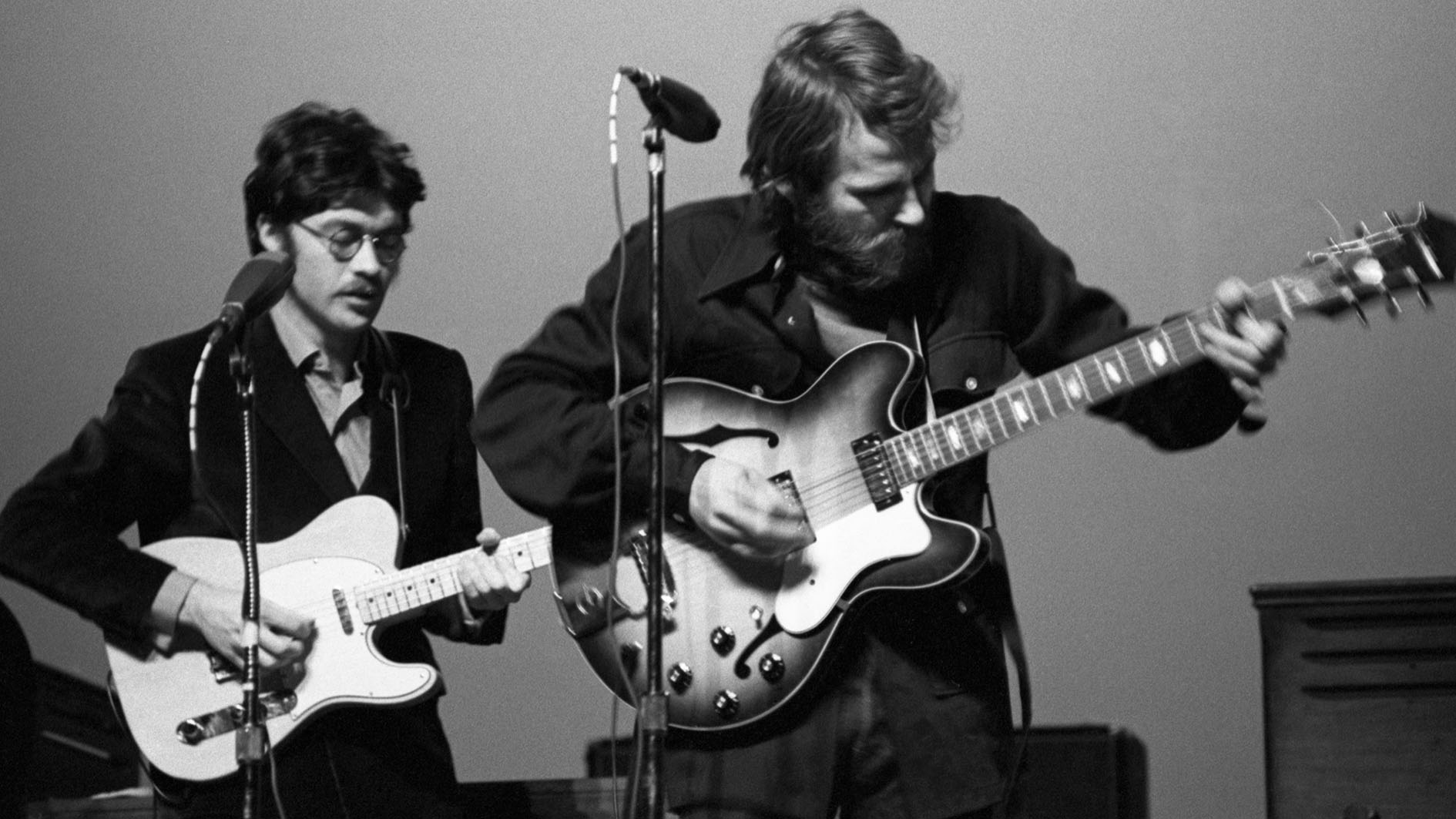

They were built around three remarkable singers – Helm, bassist Rick Danko and pianist Richard Manuel – and a fantastic batch of songs, most of them penned by Robertson, the band’s slashing lead guitarist. He wrote some of rock’s most original, indelible songs, including The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down, Up on Cripple Creek and The Weight.

The songs, which were given more depth by multi-instrumentalist Garth Hudson, sound utterly original and like folk songs that have been passed down for generations. They are so superb that Robertson’s excellent guitar playing is often overlooked.

Robertson is now 76, and has a host of new projects. Sinematic, his first album since 2011, was released in September 2019. A deluxe edition of the Band’s second (eponymous) album celebrated that landmark work’s 50th anniversary.

Once Were Brothers: Robbie Robertson and the Band, a documentary based on his 2016 memoir Testimony, debuted at the Toronto Film Festival in 2018 and was picked up for theatrical release in 2020. And Martin Scorsese’s The Irishman is the 10th movie by the director that Robertson has scored.

We caught up with the busy Robertson to discuss all of the above and a whole lot more.

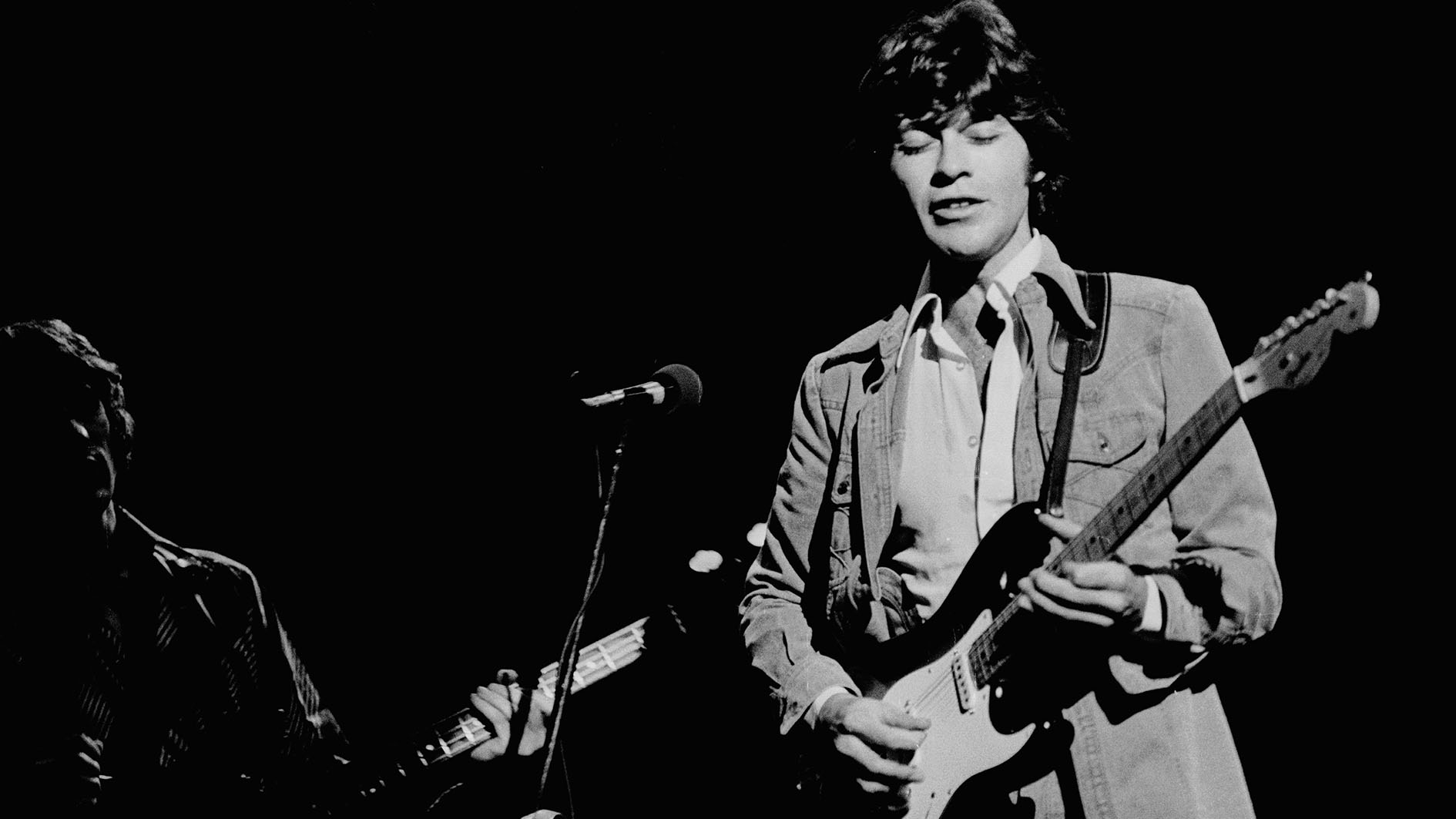

You became renowned for your songwriting, but you established yourself first as a really hot guitarist. The clips in Once Were Brothers: Robbie Robertson and the Band illustrate how your vibrato is so distinct, even from those early Ronnie Hawkins clips. Who were your biggest influences?

"When I was 16, I went from Toronto to the Mississippi Delta with Ronnie, and we went to this record store in Memphis, the musical center of the universe. It was like walking into a reservoir of sound, and I spent almost my whole paycheck on records. The sound of Hubert Sumlin’s guitar on Howlin Wolf’s I Asked for Water and She Gave Me Gasoline and Evil… man!

"And it was Muddy Waters, Robert Johnson, B.B. King, all the acoustic guys. Hearing them and their great vibratos made me determined to figure out how to do that. And one of the things nobody knew about on a large scale yet outside the South was this trick of using a banjo string for the first string, then moving the others all down one. That way the strings were looser, and you could bend them.

A lot of guitar players displayed jealousy and wouldn’t show you things: 'I had to learn myself - and so do you'

"I learned it from Fred Carter, who was the guitar player I took over from. He was from Louisiana and a lot of guitar players came through the Louisiana Hayride [radio and TV show]: guys like James Burton and Roy Buchanan. I was learning the tricks of the trade and that was my school. Ronnie recognized that there was no stopping me and said, 'Go get ’em, kid.'"

Roy Buchanan was briefly your bandmate; he seems to have already been an immense and quirky talent.

"He was amazing. A lot of people didn’t understand Roy and thought he was weird, but I really liked him, and he was very generous. A lot of guitar players displayed jealousy and wouldn’t show you things: 'I had to learn myself – and so do you.' He wasn’t like that.

"He’d show me something on his guitar, then hand it to me, but I couldn’t play his guitar! The strings were an inch off the fretboard, and I didn’t even know how he played that thing, but it just sang beautifully when he put his fingers on it."

You were 16 when you hit the road with Ronnie, a child prodigy of sorts.

"It was part of the workshop, paying your dues, learning your craft. I knew I had to do this with everything I’d got because Ronnie had an incredible, tight, driving rockabilly band, who didn’t even have bass! He made me the bass player to help acclimate me to the music and prepare to replace Fred, and I wanted to to be a part of it.

The bottom line was, there were no Canadians in a Southern rock and roll band

"I was thinking, 'Holy shit, how in the world am I going to impress these guys?' I’m inexperienced and don’t know how to play well enough, but boy, I wanted it and went on a crash course to learn. The bottom line was, there were no Canadians in a Southern rock and roll band."

And not just a Canadian – but a 16-year-old Native Canadian/Jewish kid.

"Right! I had the break down all these barriers to win, and it was such a challenge. I had obstacles to overcome that were a mile long."

If the early road was your school, what was touring with Bob Dylan in 1965 and ’66, with all those incredible shows with people virtually assaulting you as he rewrote musical history?

"It was a deep education on the magic of music and life. You couldn’t have written a more amazing story, and that forged the Band. The shit we went through was incredible. Hooking up with Bob Dylan was like entering The Twilight Zone of music. You thought, 'They’re going to wake me up tomorrow because all of this is impossible.'"

There’s an interesting clip in the film where you climb in the back of the limo after one of those shows where you’ve been assaulted with boos, and Bob says, “Well, why did they buy the tickets so fast?” That is such an interesting dynamic where the shows are so in demand yet so attacked.

"Everything was sold out! I don’t believe in history there is an equivalent story that somebody tours all over North America, Australia and Europe, and every night they boo you around the world. They’re booing this guy who revolutionized music, and we’re part of the revolution. I don’t know if this has ever happened to anybody in history. What a strange way to make a buck."

How did it impact you when you suddenly learned that your father was not your father? You’re living part time on a reservation and find out that you had a whole other family of Jewish mobsters in Toronto.

I got introduced to music on a real level on the reservation, and it was part of that culture and heritage

"And those two worlds never connected. But when my mother told me this, it was so unimaginable that I had to take it in stride because I thought, 'I just can’t freak myself out with this information.' It was a lesson about growing up: anything can happen, and you’ve got to stay standing. I just had to accept it because it was the truth."

Did the native part of your ancestry play a big role in your music?

"I got introduced to music on a real level on the reservation, and it was part of that culture and heritage. Everybody played music and I needed to be in the club, so they said, 'Well, what instrument? Do you want to play a mandolin or fiddle or drums?' I said, 'I like the look of that guitar.'

"My mom got me a guitar with a cowboy painted on it. And I thought it was so ironic that I have a guitar with a cowboy on it and Indians are teaching me how to play."

You really had that thought even at that young age?

"I did, because it was right in front of me. And one of the reasons I’m sure that the guitar appealed to me so much was seeing movies with cowboys like Gene Autry and Roy Rogers playing."

On the song Once Were Brothers on the new album, some of the background vocals and rhythms have a native echo.

"That happens quite often. It’s just there; it lives inside me."

Am I right in saying that it’s the first time you’ve directly addressed the sadness at the end of the Band in a song?

"It definitely is. As usual, I didn’t know what I was going to write about, and it just started going down that path, and just thinking that I’ve lost Richard and Rick and Levon, and it’s heartbreaking to me. I couldn’t help for it to come out in the music and in the story I was telling."

The movie addresses Levon’s anger with you and the difficulties in that relationship, which you haven’t discussed too much.

"It just came about naturally because we were really leaning on the very real story of the brotherhood. Levon and I were the closest; he was the closest thing to a real brother I ever had."

Did that make the difficulties that much more painful?

"Yes. It was painful to know what he was going through and that it was eating him up – and it had nothing to do with me. He’s a tremendous guy and a tremendous talent, somebody that I loved so much.

"When Levon said these things, I thought, 'Oh, he’s having a tough time.' And I never engaged in it at all, because I knew there was something else going on, and then I found out he had health and financial problems.

"I still completely loved him. Years later, he suddenly said I was responsible for the Band not coming back together. There was a truth in that, that I completely admit to – but I would have done it if it was doable. I was the only one that showed up."

What do you mean?

"After The Last Waltz, we wanted to talk about what we were going to do when we come back after everybody pursued some other things. We were going to meet at the studio, and I went there and nobody came or answered their phone.

"I sat there and waited, and it got dark outside and I thought, 'I’ve got to read the writing on the wall.' It was just a sign that everybody wanted to go in a different direction, and I was like, 'Okay, I get it.' And that was it. I showed up and I guess they would have if they could have."

The Irishman is your 10th soundtrack working for the same director – what is it about Scorsese that inspires you?

"Is it that many? With Marty, every movie I’ve worked on has been a completely different experience. That’s what’s so exciting about what we do together, and it doesn’t get easier because, just before I start figuring out what I’m going to do on a movie, he says, 'As long as it doesn’t sound like movie music.'"

Your album is called Sinematic, and you attribute your songwriting breakthrough to reading and studying screenplays and scripts. Can you describe how that came about?

Even at eight years old I remember going to see movies and just living inside them. It just touched a nerve deep inside me

"I became a movie bug when I was quite young. And even in the early days of playing with Ronnie, everybody would be laying around in the afternoons. I would go and see a movie and come back from Fellini so inspired and try to describe it, and everyone else’s eyes just glazed over. They thought I probably needed medical help. But I couldn’t help being so drawn to this.

"Even at eight years old, I remember going to see movies and just living inside them. It just touched a nerve deep inside me. And eventually I wondered how they did that and [poet] Gregory Corso, who was living at the Chelsea Hotel the same time I was, told me about a place called Gotham Bookmark where you could buy the scripts of Akira Kurosawa, Howard Hawks, John Ford and Orson Welles.

"Oh, my God. They revealed something to me that was very valuable and inspired me to write the stories in songs."

Didn’t playing all those shows with Dylan impact your writing? Did you study his songs in a scientific way?

"No, but they were right in front of me and I had to play them every night. He was a really close buddy of mine doing something nobody had done before. He broke down some of these walls of songs that were all about the same thing. He wrote about different things in a different way – in a different language.

"Oh, my God. There was a tremendous sense of freedom from what Bob uncovered and revealed to the world. It was like, there are no rules. Even years later when I started making solo records I found I was almost scoring the songs as opposed to strumming along or picking a little riff behind it. It was almost like it was going to be a sonic experience and that’s continued."

Alan Paul is the author of four books, including Brothers and Sisters: The Allman Brothers Band and the Inside Story of the Album That Defined '70s as well as Texas Flood: The Inside Story of Stevie Ray Vaughan and One Way Out: The Inside Story of the Allman Brothers Band – both of which were both New York Times bestsellers – and Big in China: My Unlikely Adventures Raising a Family, Playing the Blues and Becoming a Star in Beijing, a memoir about raising a family in Beijing and forming a Chinese blues band that toured the nation. He’s been associated with Guitar World for 30 years, serving as managing editor from 1991 to 1996. He plays in two bands: Big in China and Friends of the Brothers (with Guitar World’s Andy Aledort).