Sheryl Crow: the bass is my muse

The singer songwriter tells us about how bass has become central to her creative process and performances

Sheryl Crow loves bass! Some days, playing bass is all she wants to do. However, to say she arrived at the instrument a little differently than the rest of us would be as grand an understatement as, “Victor Wooten has chops.”

Crow was already a chart-topping, Grammy-winning global singing star when she caught the bottom-end bug. But more than just her favorite four strings, bass became her muse. Never has that been more apparent than on her tenth studio album, Be Myself. Crow plays bass on seven of the eleven songs, displaying the groove ethic that has always punctuated her tracks (be it via original-sounding loops or take-your-time rhythm sections).

She shows a compositional sense marked by melodic purpose, use of space, and no wasted notes, and she reveals a keen ear for tones, resulting in rich, slightly overdriven bass colors. That’s not even the instrument’s biggest role in the creative process that led to the recording—but we’ll let Sheryl, who is humbled to appear on BP’s cover, expound on that later. First, the facts:

Sheryl Suzanne Crow was born February 11, 1962, in Kennett, Missouri, to musical parents. Both her father, a lawyer and a trumpeter, and her mother, a singer, performed in big bands. Her mom was also a piano teacher, leading Sheryl and her three siblings to receive piano lessons while in grade school.

Crow began writing songs at age 13 and majored in music at the University of Missouri. She also played keyboards and sang in local cover bands, and she sang on local jingles. After graduation, she worked as a music teacher for autistic children before deciding to pursue a career in the music business.

In 1986, she packed up and drove to Los Angeles, listening to the self-titled debuts of the Pat Metheny Group [1978, ECM] and Lyle Mays [1985, Geffen] along the way.

Once in L.A., Crow traveled a diverse path to the top of the charts. She landed some jingles and successfully auditioned as a backup singer for Michael Jackson’s Bad tour, in 1987, staying two years and often dueting with the Gloved One on I Just Can’t Stop Loving You.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Back in town, she forged a studio career, singing backup on albums by Don Henley, Sting, Rod Stewart, Stevie Wonder, and Foreigner, and writing songs for Wynonna Judd, Céline Dion, and Eric Clapton.

Session work led her to producer Hugh Padgham, who got her signed to A&M. Her 1992 debut featured Vinnie Colaiuta, Dominic Miller, and Pino Palladino during his peak fretless period, but Crow deemed it too slickly produced, and she and the label mutually decided to shelve it—although it was leaked as The Unreleased Album in 1997, and it remains on YouTube.

Distraught by the project’s failure, Crow laid low for over a year before meeting a group of industry pros that included her multi-instrumentalist/engineer boyfriend, Kevin Gilbert.

Calling themselves the Tuesday Night Music Club, the crew of seven met at producer Bill Bottrell’s Pasadena studio to jam, party, and work on material. A revived Crow (the only one with a recording contract) became the unit’s centerpiece, and Tuesday Night Music Club [1993, A&M] went on to sell seven million copies and earn Crow three Grammys, powered by hits like All I Wanna Do and Leaving Las Vegas.

Her 1996-self-titled, self-produced follow up, away from the Music Club (ruptured by disputes over writing credits), included the smash singles If It Makes You Happy and Every Day Is a Winding Road, and cemented Crow’s stardom.

In the years since, Ms. Crow has released eight more studio albums, ranging from her trademark neo-classic rock to straight-up soul to singer–songwriter, country, and Christmas outings. She has also sung on numerous soundtracks and has collaborated with the likes of Clapton, Keith Richards, Stevie Nicks, Johnny Cash, Loretta Lynn, Rodney Crowell, Kid Rock, and Justin Timberlake.

Add in high-profile relationships, political stances, and health scares, and the themes of survival and being true to oneself are understandable on the critically hailed Be Myself—somewhat of a return to her rockin’ ’90s roots. And while many have seen Sheryl playing bass onstage over the years, few know how deep her bond is with the instrument, the art form, and the community. That’s where we began our wide-ranging conversation.

You’ve been writing on bass for a while. When did the instrument first become a crucial part of your creative process?

"I’d say in 1996, when I wrote my first song on bass, My Favorite Mistake [The Globe Sessions, 1998, A&M]. I’d been feeling like I was in a rut. Knowing the keyboard so well, my hands would go to those comfortable positions and familiar chord sequences. So I tried writing on bass by starting to play and following whatever melody was in my head, and that would dictate when the bass note would change.

"The bonus was it set up a deep groove for the songs. I could work with a drummer or a loop and have the bass establish the groove and have the melody determine where the song was going. The process sort of liberated me from thinking about chords and chord progressions; it took me out of a box I’d been locked into.

"I’ve been writing that way ever since, including Be Myself, which I co-wrote with my guitarist, Jeff Trott. We would get together, I’d get a feel going on bass and sing a melody, and he’d come in with chords. But basically it’s all dictated by the melody. I’m much more drawn to melodic songs now, whereas it used to be all about rocking out when I was younger."

How about your bass playing on your records and onstage?

What happened was, early on, with my limited skills on bass, I would have these awesome bass players come in and play the parts from my demos. But I noticed in some cases the replacement part didn’t feel the same, and the track didn’t sit as well, so I’d wind up doing my own bass track to capture my original feel and intent.

"As I got better at it and grew to love playing the instrument, I began playing bass at my shows on the tracks that I recorded on bass. My philosophy is it’s not a classical concert where every note has to be perfect—it’s only rock & roll, and I enjoy playing bass live."

I’m a person that loves and listens avidly to great bass playing

So we could describe you as self-taught?

"Absolutely. I just started playing by ear, as I’ve done with other instruments. But I became obsessed with it pretty quickly, and I listened to everything I could get my ears on; I was constantly playing it and applying what I’d learned.

"I’m a person that loves and listens avidly to great bass playing. Growing up in a musical family, I was one of those kids who read every album cover and knew every musician’s name. And I’ve been spoiled rotten to get to work with all of those great bass players whose names I knew, like Lee Sklar, Jimmy Johnson, Neil Stubenhaus, Nate Watts, Michael Rhodes, and Glenn Worf.

"I’ve gotten to see Anthony Jackson play. I had the good fortune of having Pino Palladino on my first album. I’ve been able to observe them all up close and absorb some of their mojo. That’s where my heart is, with great musicians who make us songwriters sound even better than we are."

Were there a few key bass influences?

"I’m a huge fan of the Carol King / James Taylor singer–songwriter era, so of course, Lee Sklar. He’s a creative freak of nature, and he has a personal depth that goes beyond his bass playing, which he brings to the table. I’m also a huge fan of jazz-based bass playing and melodic bass playing, so now we’re talking about James Jamerson and Paul McCartney.

"The grooves and musical hooks Jamerson created at Motown are indelible, and it’s the same with Paul, where you’re singing his melodies, but in your head you’re singing his bass lines. I wish I could play like that. I can’t touch any of these players we’re talking about—not even close—but even so, when it comes to my music, I feel like in some cases I’m the best man for the job because of the feel.

"I remember Sting saying what sets an artist apart are the intervals they choose and the feel they bring to their songwriting. I kind of cling to that."

It’s reminiscent of Meshell Ndegeocello and her bass players, who have all said they can’t duplicate her feel.

"She’s incredible! And a tremendous artist in her own right. We were on the Lilith Tour and she played bass on Soak Up the Sun, and it was the best version I ever heard. That’s when I’ll double back and think maybe I short-changed myself by not having more great bassists redo my tracks [laughs]. I’m such a fan of Meshell and Gail Anne Dorsey, and of course, Carol Kaye.

I hate to pinpoint female bass players, because it’s sexist to separate the quality of their playing and art by their gender, but they’re the architects. And now with amazing younger players like Tal Wilkenfeld and Esperanza Spalding, my gosh!

"I saw Tal with Jeff Beck and was blown away. You could tell she’s armed herself with hours and hours of practice and study, but the joy she exudes when she’s playing, and the intensity of the connection she has with the other musicians, is truly inspiring. It’s the same with Esperanza and her incredible acoustic bass playing and singing."

"I’ve been writing intricate melodies over independent bass lines for so long that I don’t even think about it"

Let’s talk about the Be Myself tracks that you played bass on. Halfway There is funky and has you laying off the downbeat at times.

"That song started with the bass line, before the melody and lyrics came, and we cut the track live as a rhythm section, which happened a lot on this record. Much of the album is inspired by what’s going on in our nation.

"This one was patterned along the lines of a Stevie Wonder song, like Living For The City, which tells a story from the streets and is driven by the low-end groove. Let’s not forget what an amazing [keyboard] bass player Stevie is."

The bass line is independent of your vocal. What’s your process for learning to do both live?

"I’m not really sure. Maybe it’s because I’ve been writing intricate melodies over independent bass lines for so long that I don’t even think about it. It’s simply an extension of what I do, and it’s hard to explain.

"If I could explain it, I probably couldn’t do it anymore. I’m just able to do both without thinking too much about it. My brain is hyperactive to begin with, and I find I’m even more attention-challenged as I get older."

Roller Skate has a melodic, rock–bossa bass line and a nifty bass breakdown in the bridge.

"That’s another song that started from the bass line and the melody, and changes came from there. The line is playful, as is the lyric. It was inspired by being around a skating rink in the ’70s, which is basically where I grew up. The bass breakdown was something I started doing, and we doubled it with guitar."

Your title-track bass line no doubt helped earn the “return to rock” label the record has gotten.

"That was, “Let’s write a straight ahead rock song.” It’s about young people trying to figure out who they are while following and emulating the rich and famous on their gadgets, but it turns out what’s really cool is just to be yourself.

"It was one of the first songs we wrote, and that message ended up being the catalyst for the whole album. I tried to play a steady but driving bass line, with some fills here and there."

You lock in nicely with your drummer, Fred Eltringham, throughout the album. What’s your concept when it comes to the bass–drums partnership?

"Generally, I listen to the kick and the hi-hat and try to sit squarely in the pocket. Onstage, I have just kick, hi-hat, and vocals in my in-ear, and I leave the other one out to feel the low end—and also because I don’t like singing with both in.

"I’ve gotten to play with a lot of great drummers, but Fred is my favorite. He has a deep groove, so I never have to think about the time; our feels are simpatico, and he’s a great listener. He’ll make me laugh because he’ll play something I haven’t heard before, and it always tickles me. I can feel his joy and his personality.

"That’s what you want. When you’ve got people playing your music every single night, you want them to like it and have fun with it."

Heartbeat Away has a dark bass line, with expressive slides and hammer-ons.

"That song is a bit of an homage to [the Rolling Stones’] Gimme Shelter. It’s driven by the sinister bass line and sinister drum loop, and it was pretty organic. The first and third verses happened during the recording of the demo, and we kept those takes and built the rest of the track around them."

Let’s talk about your technique

"I used to joke that I was a student of Jack Bruce, who played mostly with one finger. I need to have more technique and be able to use all of my fingers, but I’ve figured out how to best play muted and sustained notes using my alternating index and middle fingers.

"Occasionally I’ll use a thumb pluck with my index finger to grab an octave. I get around somehow; I figure out how to make it happen. Years ago, I played bass in a house cover band in New York City every Tuesday night. We had a great book and played a ton of songs from the ’70s, with people like Keith Richards, Stevie Nicks, and Mike Mills sitting in.

"I can remember having to work out how to play [the Stones’] Miss You, with all of the octaves. It was such a good training ground and the most fun ever."

You play octaves on Grow Up

I didn’t even remember! That song was written the week Prince died, so he was the inspiration. I loved Prince. When I was out with Michael Jackson, our tours overlapped a lot, so I got to see not only his arena shows but also his after-hour club shows, where he would go from playing Chick Corea-style piano to Jaco, Stanley Clarke, and Larry Graham-style bass playing; he was just crazy-articulate on every instrument.

"Once again, that song started with the bass line. I was kind of channeling Prince, with that funky, almost child-like Raspberry Beret feel."

That bass line, and Toby Gad’s bass part on Woo Woo, serve as what Will Lee calls the subhook

"Oh, that’s great—I’m gonna steal that from Will, who’s amazing, as well. I’m a big believer in the subhook, as we spoke about with Jamerson and McCartney. When you can sing a great bass line, I feel like you’re halfway there.

"Woo Woo has Toby playing the subhook of doom, and then we doubled it and funkified it with a Moog. He’s a friend of Jeff [Trott]’s who wrote All Of Me with John Legend, so when he was interested in writing together, I was all in.

"The song is about our cultural obsession with women’s derrières and the odd message it sends to young people about what represents beauty."

We’ve yet to discuss your gear. Tell me about your studio Fender and your live-preferred Guild

"The Guild came first. I started out on an old Kay bass, and I liked it; it sounded like a standup bass, but it was too difficult to play, so in 1996 I got a ’72 Guild M-85 II solidbody from Guitars ’R Us in Hollywood. I fell in love with the way it sounded, and the size and feel, and I’ve been using it live ever since.

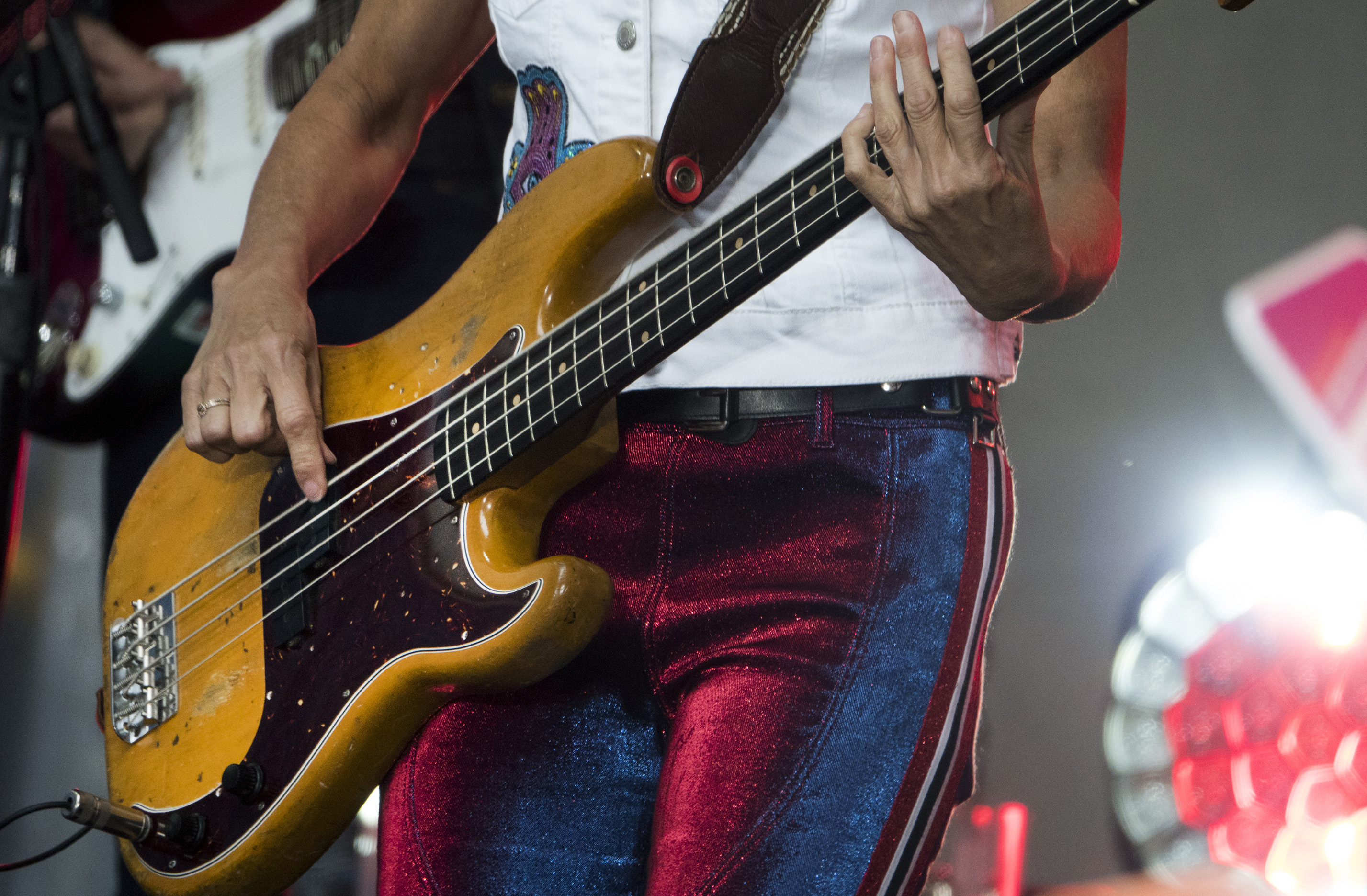

"It has a great low-end sustain, which always supports the way I play. My 1959 Fender Precision is the best bass I own. I wrote and recorded all of Be Myself with it, and it doesn’t leave my studio. When I did [famed Rolling Stone photographer] Mark Seliger’s album [Rusty Truck, Broken Promises, 2003, Coda Terra] in New York, he rented it for me, and I loved it. He somehow got the rental company to sell it to him, and he gave it to me as a gift."

Let’s talk about some of the bassists in your career, starting with your live bass players

"Robert Kearns is in my current band. He’s a very melodic bassist who brings cool new ideas to a lot of the record parts. He has a different feel than mine, so together, we cover a lot of terrain. He also plays guitar when I’m on bass.

"Before that, I had Tim Smith on tour with me for 13 years; he’s a terrific multi-instrumentalist, writer, and producer. Both of those guys, as well as Jeff, have also played bass on my albums."

Who played on All I Wanna Do and The Na Na Song?

That was Dan Schwartz on a Guild M-85 semi-hollowbody. Other favorites that come to mind are doing 100 Miles From Memphis [2010, A&M] with Tommy Simms. He’s a scary-good bass player, writer, and singer, and a deep and joyful person.

"Mike Elizondo, who has been a part of three of my records, is awesome; if I could ever get him on tour, it would be a blast, but he’s way too busy and in demand. Besides being a great producer, he’s a master at creating melodic subhooks. I’ve learned so much from being around great musicians."

Formal musical training is invaluable. But equally important is listening to and playing along with great music that has come before us

Would that be part of your advice for young musicians?

"Yes. Formal musical training is invaluable; I took piano lessons, and I loved practicing. But equally important is listening to and playing along with great music that has come before us.

"The year I spent in cover bands as a kid, doing weddings and bar mitzvahs—I wouldn’t trade that for anything, because it gives you a set of references that will serve you throughout your years of playing and writing.

"Attention spans are shorter now, and I worry that some young musicians are missing out on a priceless education by not digging into musical treasures like Motown, Stax, early British rock, jazz and big bands, folk, and country music.

"Just as important is to play those styles with musicians who are more advanced than you. That knowledge and experience will set you on your way to shaping and finding your own voice."

What’s ahead for you in 2018?

"As always, I want to keep writing, creating, and playing. We have an EP in the can, a highly collaborative record I made with [drummer] Steve Jordan, which will be out in 2018. And I’ve been vowing to study with some bass players. Appearing in Bass Player is certainly incentive to finally make it happen!"

Equipment

Basses: 1972 Guild M-85 II BluesBird (cherry finish, solidbody); 1959 Fender Precision Bass (rosewood board, stripped natural finish)

Strings: D’Addario EXL170M Nickel Wound Bass (.045, .065, .080, .100)

Rig: Ampeg Classic Series SVT-VR head and SVT-212AV cabinet. According to Rick Purcell, Sheryl Crow’s production manager and guitar tech: “Sheryl keeps the amp settings fairly flat, with the bass cut engaged, because her Guild pickups are loud and bottom-heavy.”

Other: Shure U4D Wireless, Jodi Head Straps, Planet Wave cables

Recording Be Myself: “Sheryl’s signal path was her ’59 P-Bass, with fairly new roundwound strings, into an ADL DI200 Stereo Tube DI, to an API 512C mic pre, to an API 550A EQ, to an Empirical Labs EL8 Distressor. She also had a mic'd vintage Ampeg B-15 signal.”

Chris Jisi was Contributing Editor, Senior Contributing Editor, and Editor In Chief on Bass Player 1989-2018. He is the author of Brave New Bass, a compilation of interviews with bass players like Marcus Miller, Flea, Will Lee, Tony Levin, Jeff Berlin, Les Claypool and more, and The Fretless Bass, with insight from over 25 masters including Tony Levin, Marcus Miller, Gary Willis, Richard Bona, Jimmy Haslip, and Percy Jones.