Steve Miller is best known as the creator of classic rock staples like The Joker, Fly Like an Eagle, Rock’n Me and Jungle Love. The Steve Miller Band’s Greatest Hits 1974-78 collection has sold more than 13 million copies, making it one of the top-selling rock albums of all time. But before all of that, Miller, who grew up in Dallas, began his career as a bluesman – and he is thoughtful and insightful about the music’s history.

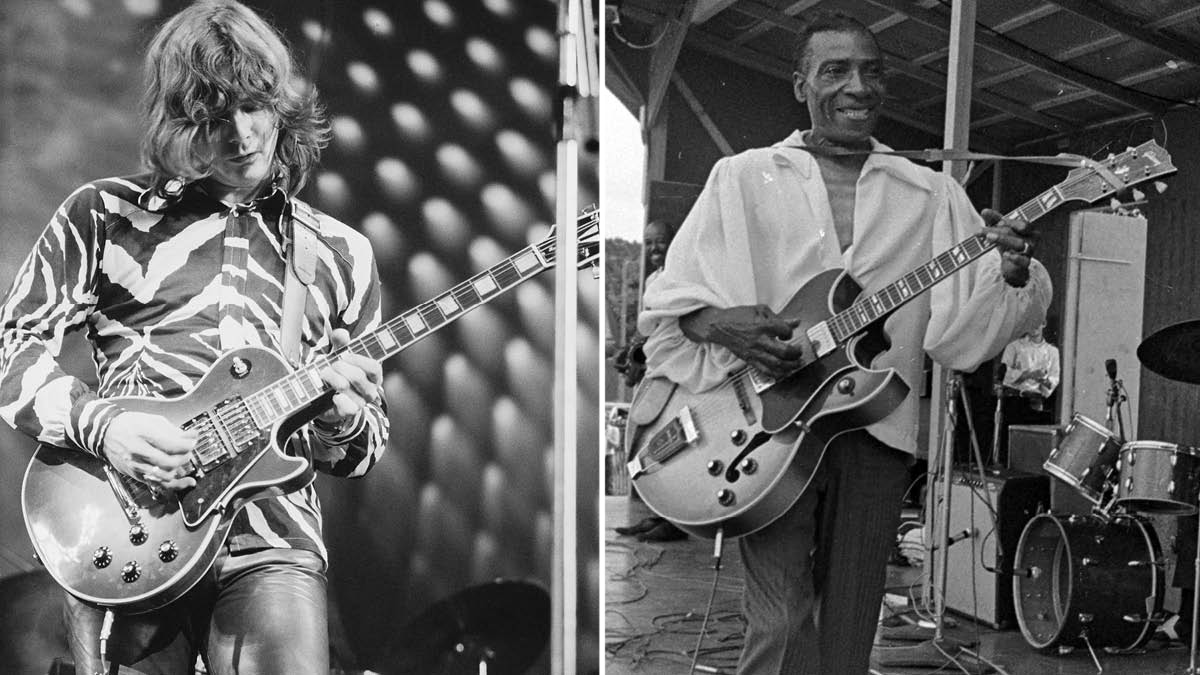

Miller considers T-Bone Walker to be the father of modern blues guitar, and he has an extra-personal reason for making sure the Texas great’s legacy is properly respected: Walker was a family friend who taught the nine-year-old future legend his first licks. He was happy to share his thoughts about the blues icon.

What makes T-Bone such an important figure in the history of the electric guitar?

“It’s all about the changeover from country blues to city blues. T-Bone was one of the very first guys who played electric guitar, along with Charlie Christian, who was a good friend of his. When T-Bone bought his Gibson guitar in 1936, it changed everything! T-Bone was the first guy through the gate and he was maybe the smartest, the most sophisticated and most interesting musically. He’s like the Duke Ellington of country blues.

“He watched jazz guys and picked up chords, and all of a sudden he’s written Stormy Monday Blues. That changed the way electric blues is played. Nobody else played anything like that, and he opened the door. A whole lot of people said, ‘I want to do that.’ B.B. King, Freddie King, Albert King, Eric Clapton, Jeff Beck, Stevie Ray Vaughan and every other blues and rock electric guitarist who has come down the pike started there.

“You go from the staccato jazz licks to the fat, soaring Albert King lead guitar and, of course, Chuck Berry, the father of rock guitar whose primary licks all came from T-Bone.”

But he wasn’t actually the first guy to play an electric guitar.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“Les Paul had built an electric guitar and amplifier and was recording with Bing Crosby, and it was all brand-new stuff. T-Bone heard that and adapted. Before that, he was playing banjo because it would cut through the orchestra, and that explains a lot about his playing.

“When he first started doing the splits and all that, he was doing it with a banjo! He started figuring out the instrument by just going, ‘Hmm, electric guitar… what is this?’

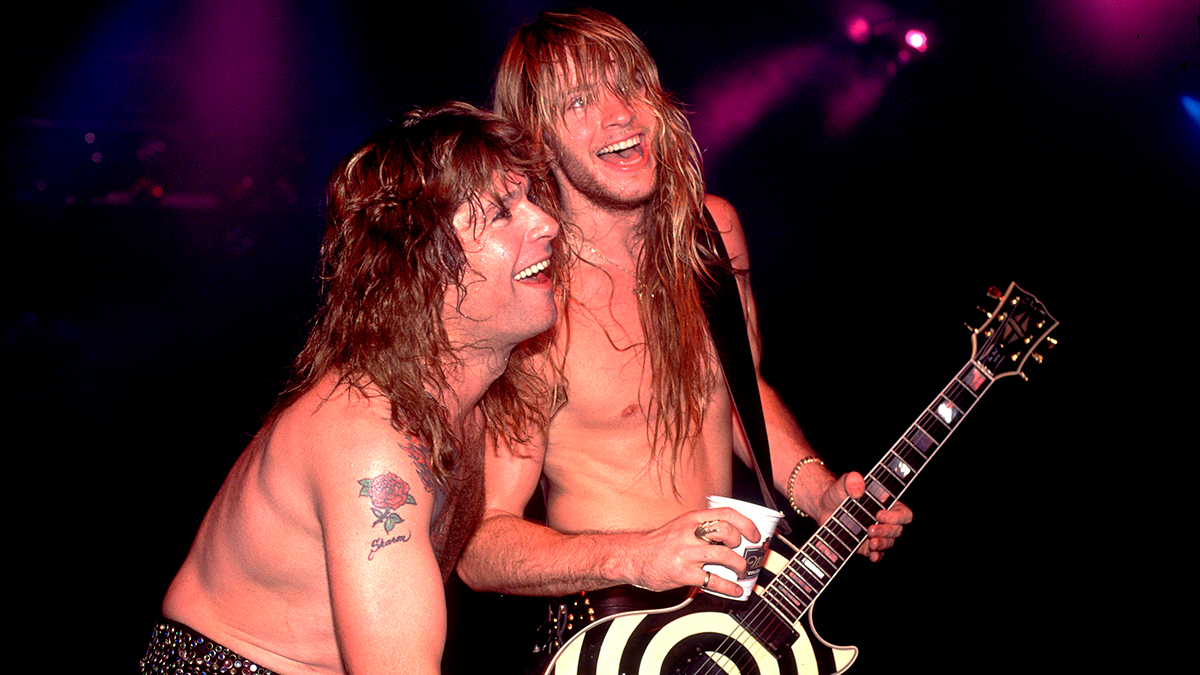

T-Bone was also a showman who spoke about his performance as an act. He ran across the stage and slid on the floor and squatted down and played behind his head

“He was very sophisticated, hanging out in New York when Charlie Christian was revolutionizing music with Benny Goodman at Carnegie Hall. They were living in the same building. Charlie was really sick with tuberculosis, and he would just come home and play all night – and then in a minute he was gone. T-Bone was also a showman who spoke about his performance as an act. He ran across the stage and slid on the floor and squatted down and played behind his head.

“All that stuff really came from him as well. Of course, Chuck Berry was also a brilliant performer and he had an act, just like T-Bone Walker had an act. He duckwalked and had the greatest lyrics for kids, and he had Johnnie Johnson playing boogie-woogie piano behind him and he had learned all of his T-Bone stuff.”

How’d you meet T-Bone as a kid?

“My father was a pathologist who ran the lab at a hospital in Dallas where T-Bone received treatment for severe stomach ulcers in the late ’40s, early ’50s, when no one knew what ulcers were or how to fix them. My father was a music nut and he had a tape recorder, which was like having something from Mars back then.

T-Bone was a sweet, patient man and a brilliant musician, and I got to sit at his feet and watch him play for five or six hours at a time

“He became friends with T-Bone, who became a visitor at our house, and played a couple of times, which my father recorded in 1951 and ’52. This was T-Bone Walker at his peak doing 17 songs that he didn’t record for a label. T-Bone was a sweet, patient man and a brilliant musician, and I got to sit at his feet and watch him play for five or six hours at a time.

“You know what’s really crazy? Les Paul taught me my first chords in Milwaukee, T-Bone taught me how to play lead when I was nine, and I ended up recording with Chuck Berry and backing him up in California. I ended up with all these guys.”

I imagine that a Black musician hanging out at your house in Dallas caused some issues in 1951.

“Oh, yeah. Dallas was completely segregated. We moved there from Milwaukee when I was five. And my parents always had a lot of musician friends. Les Paul was my godfather and he used to come around the house all the time, and so did people like Charles Mingus and Tal Farlow. They’d come to town, play hip gigs Saturday night and have lunch at our house on Sunday.

Les Paul was my godfather and he used to come around the house all the time, and so did people like Charles Mingus and Tal Farlow

“But in Texas, we went through all sorts of stuff. My father was sort of considered a communist and he was arrested and handcuffed, with his picture on the front page of the newspaper for having a ‘race party’ in his lab because he had a holiday party that included Black lab technicians.

“They made him sound like a real sleazy guy, but my dad was a great guy and real smart. Everybody loved my mom, so it was hard to be mad at them. One thing that helped them is we Texans loved our music, so it was normal to be into jazz, and Carl Perkins and T-Bone Walker and Bob Wills.”

Alan Paul is the author of four books, including Brothers and Sisters: The Allman Brothers Band and the Inside Story of the Album That Defined '70s as well as Texas Flood: The Inside Story of Stevie Ray Vaughan and One Way Out: The Inside Story of the Allman Brothers Band – both of which were both New York Times bestsellers – and Big in China: My Unlikely Adventures Raising a Family, Playing the Blues and Becoming a Star in Beijing, a memoir about raising a family in Beijing and forming a Chinese blues band that toured the nation. He’s been associated with Guitar World for 30 years, serving as managing editor from 1991 to 1996. He plays in two bands: Big in China and Friends of the Brothers (with Guitar World’s Andy Aledort).