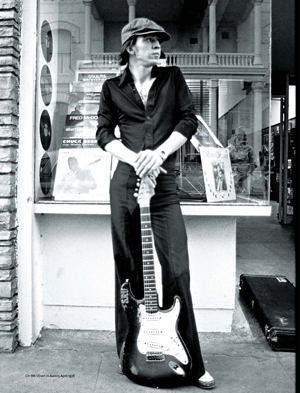

Stevie Ray Vaughan: Lone Star Rising

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Through the recollections of Stevie Ray Vaughan’s earliest bandmates and friends, Guitar World presents an unprecedented in-depth look at the Texas blues player’s youthful years as a struggling guitarist.

Nineteen eighty-three was a banner year for guitar fans. Eddie Van Halen contributed a blistering solo to Michael Jackson’s chart-topping hit “Beat It.” Bands like ZZ Top, Judas Priest and Def Leppard broke through to new heights of multi-Platinum success, and newcomers like Yngwie Malmsteen and Metallica made indelible first impressions that would forever change the way guitarists viewed their instruments.

But one of 1983’s biggest guitar success stories was also one of its unlikeliest: the phenomenal rise of a previously unknown 28-year-old blues guitarist from Austin, Texas, named Stevie Ray Vaughan. In the span of a few short months, Vaughan made an auspicious mainstream debut by playing on David Bowie’s 1983 hit album Let’s Dance. Then, in a move that stunned everyone, he turned down a worldwide tour with Bowie’s band and released his own album, Texas Flood. The record single-handedly revived the popularity of the blues for the first time since the late Sixties. Music industry veterans and journalists wondered why they had never previously heard of this cocky, not-so-young upstart who could play like both Albert King and Jimi Hendrix and who was the younger brother of Jimmie Vaughan of the Fabulous Thunderbirds.

But Stevie Ray Vaughan was no stranger to a select audience of music fans who closely followed the blues scene in Dallas and Austin during the Seventies and early Eighties. In fact, many of them could remember seeing a young, wiry kid named Steve Vaughan tearing it up in clubs before he was even old enough to drive. The story of how he became a blues legend is a fascinating tale of hard work, relentless persistence and deep passion for a style of music that even most of its biggest supporters weren’t sure would ever again surpass the peak it reached in the Sixties.

As Craig Hopkins details in his new book Stevie Ray Vaughan: Day by Day, Night After Night chronicle the thousands of gigs, Vaughan had numerous close but mis-timed brushes with fame and fortune over the years. Hopkins tracked down many of Vaughan’s former bandmates to he played with various bands before he finally got his big break. In doing so, he presents a vivid picture of the guitarist in his youth, before he became known to millions.

IN THE BEGINNING

In numerous interviews, Stevie said that his brother Jimmie was the biggest early influence on his playing. Jimmie had already been playing guitar for a few years when Stevie got his first guitar, a steel-string acoustic decorated with stenciled cowboy illustrations that his father bought at Sears as a present for his seventh birthday, on October 3, 1961. Jimmie taught him a few basic chords, but he essentially taught himself how to play by ear, learning songs like “Wine, Wine, Wine” and “Thunderbird” off of a 1962 album by Dallas rock and roll band the Nightcaps. “Baby What You Want Me to Do” by blues guitarist Jimmy Reed was another early favorite.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Sometime in 1963, Stevie walked into a record shop near his home in the Oak Cliff section of Dallas and asked the sales clerk to give him the wildest guitar record that he knew of. Fortunately, the clerk had good taste, as he recommended Lonnie Mack’s latest single at the time, a relentless R&B instrumental called “Wham!” that featured lightning fast runs and radical whammy bar work. Stevie spent countless hours figuring out how to play the song, practicing on his first electric guitar—a Gibson ES-125T with a single P90 pickup in the neck position that was a hand-me-down from his brother. Almost 20 years later, he recorded a cover of “Wham!” for his debut album, and in 1985, he produced Mack’s comeback album, Strike Like Lightning.

Stevie had been playing almost three years when he made his first public performance on June 26, 1964, at a roller rink called the Cockrell Hill Jubilee in Dallas. His band, which consisted of a few friends who also played instruments, was called the Chantones. Reportedly, they played only one song—Jimmy Reed’s “Baby What You Want Me to Do”—and witnesses say none of the band members knew how to play it all the way through. Stevie recalled being told that “one day he’d be as good as Jimmie,” who, though only 13, was already developing a reputation around Dallas as a great guitar player.

Over the next two years, Jimmie started playing gigs professionally and joined bands featuring players much older than him. Stevie struggled to keep up, learning how to play current rock and roll hits such as the Animals’ version of “House of the Rising Sun,” “Gloria” by Them and “Don’t Let the Sun Catch You Crying” by Gerry and the Pacemakers. In 1966, singer and drummer Doyle Bramhall hired Jimmie to play with his band, the Chessmen. This was the beginning of a long musical relationship between Bramhall and the Vaughan brothers.

Bramhall recalled for Hopkins the first time he met Stevie and heard him play, “I was sitting in [the Vaughans’] living room waiting for Jimmie. When Jimmie walked from the back bedroom to the kitchen I heard this guitar playing coming from the other direction. I walked down the hall, and a bedroom door was a little ajar. I looked in, and there was this little skinny 12-year-old kid sitting on the bed playing the Yardbirds’ ‘Jeff ’s Boogie.’ As soon as he saw me, he stopped playing, and I said, ‘Don’t stop.’ Stevie always made it look easy. Even at the age of 12, he definitely had a feel for the guitar.”

LUCKY 13

During the summer of 1967, while Stevie was only 13, three events transpired that would have a huge impact on his future. The first occurred while he was rummaging through the trash bins behind the Dallas TV studio where a local live teen dance program called Sump’n Else was filmed. Among the garbage, he found a 45-rpm record of Jimi Hendrix’s “Purple Haze,” a song that woke him up to a wild new style of guitar playing. The second took place while he was working as a dishwasher at a burger stand. He fell into a 55-gallon barrel of grease, a humiliation that made him determined to make a living playing with his guitar. The third incident happened when Jimmie moved out of his parents’ house and got his own apartment, leaving behind a 1951 Fender Broadcaster that Stevie began to play. Finally, Stevie had a guitar with which he could produce the sounds of his favorite rock and blues players.

Shortly afterward, Stevie joined his first real band, the Brooklyn Underground, which played at local “sock hops,” high school dances held in the school’s cafeteria or gym. In Hopkins’ book, guitarist and bandmate Paul Kessler recalls, “The main reason we got Stevie in the band was because we considered Jimmie the best guitar player in Dallas. We thought maybe some of that [luck] might rub off on us. I remember that Are You Experienced had just come out, and Stevie jumped on that stuff pretty quick. His influences at the time were his brother, Jimi Hendrix, Eric Clapton and Jeff Beck, and we played songs by the Beatles, Kinks and Yardbirds.”

Randy Martin, who played bass in the Brooklyn Underground, told Hopkins, “[Stevie] loved Hendrix. When he’d start playing a lead in a song, people would turn around and gravitate toward the stage to see this little kid play guitar. He wasn’t refined back then. He had nervous energy and didn’t know how to put it all together, but it was incredible to see a little kid play guitar like that. He had a gift.”

About a year later, Stevie got to witness his two biggest influences playing a gig together when his brother’s band, the Chessmen, opened for the Jimi Hendrix Experience at the State Fair Music Hall in Dallas on February 16, 1968. Stevie became more determined than ever to follow in his brother’s footsteps, but his overprotective father, who wasn’t thrilled about Stevie’s musical aspirations at such a young age, refused to let him play in establishments where liquor was served and put Stevie’s plans on hold.

Although there wasn’t any blues scene to speak of in Dallas during the late Sixties, many blues legends frequently passed through town to play gigs. In 1969, Stevie, then 14, started hanging out at R&B and soul clubs where touring blues acts frequently played, and occasionally he talked the club owners into letting him sit in with the bands. “I used to ride a cab down to Hall Street in Dallas,” Vaughan told Andy Aledort for an interview published in the December 1990 issue of Guitar for the Practicing Musician. “I’d sneak in the clubs to see T-Bone Walker and Freddie King. It was around the same time that Eric Clapton was [playing blues], and it was like, ‘Oh, it’s okay for me to do this. Somebody else is doing it who’s not black.’ ”

When his bandmates in the Brooklyn Underground became frustrated with having to hire a backup guitarist whenever they played shows at establishments that served alcohol, Stevie and the band parted ways. He went on to join the Southern Distributor, which was focused on creating big productions rather than playing casual club gigs. The band’s business card boasted “solid sound” and a “psychedelic light show,” and described the music with a de rigueur Sixties hippie-dippie phrase: “pseudopsychosonicoptic.”

The band’s rhythm guitarist Patrick McGuire told Hopkins that Stevie played a perfect note-for-note version of “Jeff’s Boogie” at his audition: “We were all astounded at how well he played for his age. He played intricate songs like ‘Jeff’s Boogie,’ which were difficult even for guys quite a bit older. He was into the old blues artists. He practiced at least five hours a day and didn’t have much social life. All he did was play guitar. He lived, ate and breathed guitar. That was it.”

The Southern Distributor played covers of songs by the usual pop rock bands of the day—the Beatles, Doors, Cream and the Rolling Stones—but Stevie expressed a desire to add blues songs to the band’s repertoire. This was one of the first of numerous times in Vaughan’s career that he was told that he wouldn’t make any money playing the blues. Instead, he sought out satisfaction by going to clubs and sitting in with other bands. Bassist Tommy Shannon, who was playing with Johnny Winter at the time and later played bass in Double Trouble, recalls seeing Vaughan play for the first time when Stevie was sitting in with a band at the Fog club in Dallas. A short while afterward, Vaughan jammed with Winter at the Cellar. He made enough money playing with the Southern Distributor to afford his first Fender Stratocaster, a 1963 model with a maple neck.

STEVIE'S LIBERATION

Although Jimmie and Stevie’s paths rarely crossed in the early days, for about two months they played in the same band together when Stevie was recruited to play bass with Jimmie and Doyle Bramhall’s band, Texas Storm. That union was cut short when Jimmie and Doyle decided to move to Austin in May 1970. Stevie then auditioned on bass for the band Liberation, but as Hopkins notes, when the band’s guitarist Scott Phares heard Stevie play guitar during a break, he humbly decided to step aside to a role as the band’s bass player and let Stevie play guitar.

Liberation was a huge band that had a multi-piece horn section and up to 12 members. While Liberation’s main focus was playing covers of songs by bands like Chicago and Blood, Sweat and Tears, they also played songs by Cream, Jimi Hendrix and Led Zeppelin as well as a variety of blues covers like “Hoochie Coochie Man” and “Hideaway.”

Liberation drummer Mike Day recalls, “When we played blues, black people would come up to Stevie and say, ‘You’re black!’ I think that meant more to him than any of the accolades that anybody else showered on him.”

During the summer of 1970, while Liberation was playing at a club called Arthur’s located in Dallas’ Adolphus Hotel, a newly signed local band called ZZ Top dropped in and asked if they could play two sets for free. Recollections from the many witnesses vary, but everyone recalls that Vaughan and Billy Gibbons jammed together on a cover of a Nightcaps song (either “Wine, Wine, Wine” or “Thunderbird”).

“They tore the house down,” Phares told Hopkins. “It was one of those magical evenings. Stevie fit in like a glove on a hand. He had a real long guitar cord, and whenever he took off into a solo, he’d jump off the stage and go walk around. All the dancers would watch him play his ass off. He was quite a showman.”

Vaughan’s confidence as a player and performer began to grow. He started to dress like a rock star, wearing cowboy hats with long feather plumes, sequined jackets adorned with ostrich feathers, and sunglasses. When Vaughan got harassed and threatened by some of the more conservative members of Dallas society, he just became more determined and dressed even more outlandishly.

In the fall of 1970, he participated in his first studio recording session (his only previous recording was a live jam with the Marc Benno band in 1969). The project was a compilation album called A New Hi, which featured rock bands from numerous high schools around the Dallas area. Vaughan (whois credited on the album as Steve Vaughan) sat in with a band formed by his classmates at Justin F. Kimball high school called A Cast of Thousands to record two songs—“Red, White and Blue” and “I Heard a Voice Last Night.” (Streaming MP3 recordings of the songs can be heard at www.kimballclassof70.org/castofthousands.htm.) Vaughan’s tone and phrasing on both songs is reminiscent of Cream-era Clapton, and his performance reveals impressive maturity and skill.

Shortly after making the recording, Vaughan dropped out of high school, grew his hair long and started concentrating on a career as a professional musician. By 1971, he grew tired of playing pop hits, so he quit Liberation and formed the band Blackbird, which performed songs by more adventurous artists like the Allman Brothers, Janis Joplin and west coast blues legend Lowell Fulson. Vaughan started playing slide guitar and learned many of Duane Allman’s parts from Allman Brothers records.

While playing with Blackbird, Vaughan traded his 1951 Broadcaster for a thinline semihollow Epiphone Riviera with mini humbuckers that was owned by Geoff Appold. “I asked him why he wanted that Epiphone,” Appold told Hopkins. “He said, ‘Well, Freddie King was everything to me, and I wanted to be like him, with a hollowbody Gibson.’” Appold recalls that even back then Vaughan had already developed a preference for heavy strings.

Blackbird frequently traveled to Austin to play gigs, because most clubs in Dallas would hire only bands that played Top 40 covers. By the end of the year, the entire band relocated to Austin. Despite the city’s current status as the capital of Texas blues, back in 1972 there was no blues scene to speak of and only a few clubs hosted blues bands and performers (Antone’s didn’t open until 1975). Even so, audiences in Austin were more adventurous and tolerant of non-mainstream music styles, so it was easy for Blackbird to find plenty of regular gigs.

Unfortunately, it was more difficult for Blackbird to find a consistent lineup (Tommy Shannon played bass in the band for about a month), and by the end of the year, Vaughan joined Krackerjack, which was a “Led Zeppelin–style” band. With Krackerjack, he played a handful of high-profile concert gigs, opening shows for Wishbone Ash, Sugarloaf and Wet Willie. He left Krackerjack after playing with the band for just three months. His replacement was Gary Myrick, who later recorded the new wave hit “She Talks in Stereo” with Gary Myrick and the Figures in 1980.

WELCOME TO HOLLYWOOD

In March 1973, Vaughan and Doyle Bramhall became members of Marc Benno and the Nightcrawlers. Benno was an established singer-songwriter/guitarist from Dallas who had worked with Leon Russell and the Doors (he played rhythm guitar on L.A. Woman) and had already released three solo albums with A&M Records. Benno flew Vaughan and Bramhall out to Hollywood to participate in recording sessions at Sunset Sound for what was supposed to be Benno’s fourth album. Outside of Texas, Vaughan had previously played only a handful of gigs in the South, and it was his first trip to California.

Although A&M passed on the album (Benno finally released it independently in 2006 with the title Crawlin’), the experience greatly accelerated Vaughan’s growth as an artist and performer. He wrote his first songs—the title track and “Dirty Pool”—and Bramhall taught Vaughan how to sing. He also met a handful of big-name stars who were working at or visiting the studio, including former Beatles George Harrison and Ringo Starr, former Monkee Mickey Dolenz, Kris Kristoffersen and pop crooner Andy Williams. The Nightcrawlers also toured the U.S. as an opening act for Humble Pie and the J. Geils Band.

“[It was the first time that] Stevie got to see a big tour and full-blown recording,” Benno told Hopkins. “Stevie was not born in a club in Austin and then discovered. He had that Hollywood experience and some business experience, too. He took all of that back to Austin along with all the soul he already had.”

Most performers who experienced such a close brush with fame and fortune would pursue an even more pop focus, but Vaughan turned 180 degrees when he went back to Austin and began to play jazz and dig deep into the blues. He learned how to play Wes Montgomery–style octaves and taught himself to play the classic blues standard “Texas Flood” by Larry Davis. Although Vaughan had used a Marshall stack since he joined Blackbird, he switched to Fender Twin Reverb and Super Reverb amps instead.

Doyle Bramhall recalls, “We were getting into more soul and funk kind of music and jazz and listening to all these great jazz records. Band-wise, we started to work more on dynamics—bringing the song up and coming down real quiet with it.”

Although Benno had dropped out of the Nightcrawlers, manager Bill Ham (who also managed ZZ Top) took interest in Vaughan and Doyle and started booking gigs for their band. Many of the gigs were disastrous. In one instance they drove all day to Little Rock, Arkansas, only to find out the club had switched to country and western a few weeks before. But they also played a handful of high-profile shows opening concerts for Charlie Daniels, ZZ Top and Kiss, who were on their first tour.

In 1974, progressive country artists like Willie Nelson, Jerry Jeff Walker and Michael Murphy dominated the music scene in Austin, and gigs became harder to find for rock and blues bands. Bruce Bowland, who was the lead singer of Krackerjack, told Hopkins, “That was a real hard time for everybody in Austin. We all thought we were bulletproof, that no one could touch us, and then this movement called progressive country came out and kicked our ass. Although rock and roll was still happening, it wasn’t happening as big. It was like the wheels just fell off of everything.”

The Nightcrawlers’ deal with Bill Ham fell apart, and Ham left the band stranded in Mississippi without any means or funds to make it back home. Ham also demanded reimbursement from Vaughan for all the equipment that Ham had bought for him. Despite being essentially broke, Vaughan later managed to gather enough money to buy the battered 1962 Stratocaster that became known as “Number One” from Ray Hennig at Heart of Texas Music in Austin.

“When he came in, like every other day, we had a long row of guitars,” Hennig told Hopkins. “And he wouldn’t take them off the hook. He’d simply walk down and feel them and look at them and move on to the next one. He stood there and looked at that old thing, and I thought, Oh no. Then he reached down and felt of it, just like he did always. And then he took it off the hook, hitting some licks on it. He said, ‘Ray, where’d you get this?’ I said, ‘Stevie, you have got to have picked the biggest junker on the wall.’ ”

Apparently, beauty is in the eye of the beholder. Previously, the Strat had belonged to Austin musician Christopher Cross, who later became known for the adult-contemporary hits “Sailing” and “Ride Like the Wind.” Even with the years of abuse that Vaughan added to the guitar, its value today should it ever be sold auction is estimated at well in excess of a million dollars.

FIRST RAYS OF THE NEW RISING SUN

In 1975, Vaughan joined a six-piece band called Paul Ray and the Cobras. The band played gigs all over Texas and earned a regular stint at a newly opened Austin club called Antone’s, where Jimmie Vaughan’s new group, the Fabulous Thunderbirds, was also the house band. “I was able to play with so many of my idols at Antone’s,” Vaughan told Request magazine. “Buddy Guy, Otis Rush, Hubert Sumlin, B.B. King, Jimmy Rogers, Lightnin’ Hopkins and—the biggest thrill for me—Muddy Waters. Howlin’ Wolf was scheduled to play at Antone’s, but he died a week before. That broke my heart.”

Eric Johnson, another Austin legend, recalls seeing Vaughan perform for the first time when Vaughan was a member of Paul Ray and the Cobras. Johnson and Vaughan became friends (their girlfriends at the time were best friends), but Vaughan initially turned down offers to see Johnson’s band, the Electromagnets, because Vaughan wasn’t into the fusion-style jazz that they played. When he was finally convinced to see them perform, he became a big fan of Johnson’s playing, and they started to jam together occasionally.

“Watching Stevie and Eric play together was something else,” says Joe Sublett, who played saxophone with the Cobras. “[When they played] they both moved toward a common ground, which was that Jeff Beck/Eric Clapton sort of vocabulary that they both had in common. Eric played less like a fusion guy and more like Jeff Beck, and Stevie played more like Jeff Beck–meets–Eric Clapton. It was something I hadn’t heard either one of them do before.”

In late 1976, Vaughan recorded the single “Other Days”/“Texas Clover” with Paul Ray and the Cobras. The reggae-flavored “Texas Clover” featured a relatively subdued performance by Vaughan that provided few hints of his powerhouse style, but his solo on the funky soul tune “Other Days” revealed much of that distinctive personality that later made him a star. The single’s credits list him as “Stevie Vaughan”—he was not using his middle as part of his stage name yet. The single came out in February of 1977, and in March, Paul Ray and the Cobras were named Band of the Year in the Austin Sun’s readers’ poll. The accompanying article was the first instance where Vaughan was identified as “Stevie Ray Vaughan.” Photos taken around this time also reveal that Vaughan had added his iconic “SRV” stickers to his Number One Strat sometime in 1977.

While Vaughan had spent much of his playing career up until this period backing up other musicians, he finally started to assert himself as a star in his own right around this time. With the Cobras he had become confident enough in his own vocal abilities to sing lead on a few songs, and he briefly took over frontman duties when Paul Ray had to take temporary leave due to a throat problem. When the Cobras decided to pursue a more mainstream direction, Vaughan left in August of 1977 to form the Triple Threat Revue with singer Lou Ann Barton and blues guitarist/singer W.C. Clark.

The all-star Triple Threat Revue became a popular draw in Austin. Billy Gibbons often dropped in to see the band play its regular Monday night shows at the Rome Inn, which became the inspiration for the song “Lowdown in the Street” on ZZ Top’s Deguello album. Vaughan’s main guitar during this time was a late-Fifties Rickenbacker Model 360 semihollow guitar, although he broke out Number One to perform a handful of instrumentals, like “Texas Flood.”

Austin guitar dealer Tony Dukes told Hopkins about Gibbons’ reaction when he saw Vaughan playing a Rickenbacker: “Billy wanted to see it, so he walked up [to the stage] and turned around with this horrible expression on his face. The strings were so high and so big he couldn’t make a note on it. He was amazed that Stevie could play it.”

In addition to stepping out more often as a frontman, Vaughan started to write his own songs. In 1978, he wrote a pair of similar blues shuffles, “I’m Cryin’ ” and “Pride and Joy,” which later became one of his signature tunes when he recorded it for his debut album. He also penned an instrumental song that later became known as “Rude Mood,” and used it to warm up the audience before the band’s singers joined him onstage. In July, he wrote “Love Struck Baby” for his new girlfriend, Lenora “Lenny” Bailey.

Several members of the Triple Threat Revue had left or changed, so Vaughan now named the band Double Trouble, after an Otis Rush song. Lou Ann Barton still sang a few songs, and drummer Chris Layton joined the band in September. Johnny Reno, who played sax with Double Trouble, says, “The summer of ’78 he became the Stevie Vaughan that everybody really dug. Before that he was known as a sideman. That summer he really [developed] his artistry. He would play ‘Little Wing’ at three o’clock in the morning at the Rome Inn and stretch it out for an hour with just him, a bass player and a drummer. That’s where Stevie wanted to go, and that’s where people in the music business wanted him to go. They weren’t interested in a band with a chick singer and a sax player doing Fifties R&B covers from Chicago. All of a sudden Stevie became a rock guitar player.”

Reno was first to see the writing on the wall, and he quit Double Trouble in the summer of 1979. Barton wasn’t supportive of the Jimi Hendrix songs that Vaughan wanted to perform, so she left a few months later in November while the band was on tour on the East Coast. “When Lou Ann left the band, we became a power trio,” Layton says. “There was only one direction to go, and a whole different style of music grew out of that. We started doing some Hendrix-type stuff, and his guitar playing got a lot more wild. He started playing behind his head, between his legs and behind his back—a lot more stage antics.

RESURRECTING THE BLUES

Double Trouble hooked up with manager Chesley Millikin in 1980, which was a crucial step toward making the band a national phenomenon. Millikin was previously the general manager of Epic Records in London, England, and he had worked with the Rolling Stones, the Grateful Dead and Jackson Browne. Millikin knew that Vaughan was a star, so he tried to convince Double Trouble to use just Stevie’s name, thinking he could easily replace the other members if the need arose. The band resisted, and as a compromise all parties agreed to call the band Stevie Ray Vaughan and Double Trouble.

Like so many who came before him, Millikin was not convinced that a viable market existed for the blues, so he refused to promote Vaughan as a bluesman. He turned down an offer from Takoma Records, a folk-oriented label that had recently signed Jimmie’s band the Fabulous Thunderbirds, and waited for bigger offers to come along.

Bassist Tommy Shannon recalls seeing a Double Trouble show at Rockefeller’s in Houston in October 1980. Blown away by Vaughan’s stage presence and playing, he became determined to join the band. “That was where I wanted to be,” Shannon admits. “That’s where I belonged. During the break, I went up to Stevie and told him that. I didn’t try to sneak around and hide it from the bass player. I really wanted to be in that band.” Shannon’s wish was fulfilled a few months later, in January 1981, when he joined Vaughan and Layton as Double Trouble’s new bassist.

Eric Johnson says that all of the elements for Vaughan’s inevitable success were finally in place. “When Stevie got together with Tommy Shannon, it was like magic unleashed. The three of them had a chemistry that completely shifted the band’s direction. The potential was there before, but it was like all the fire was contained. With Tommy in the band, you could tell that something really heavy and profound was happening.”

One day in early 1982, Mick Jagger dropped by the horse-racing track Manor Downs to view some thoroughbreds. Millikin was also the general manager of the track, and he passed a videotape of one of Vaughan’s performances to his old friend. A few days later, Stones drummer Charlie Watts called Millikin and asked when he and Mick could see Vaughan play. Millikin hastily arranged a private showcase party in New York City at the Danceteria nightclub in April. Aside from members of the Rolling Stones, only a handful of people showed up, but a photograph and an article about the party appeared in Rolling Stone magazine. Rumors spread that Vaughan was going to sign a deal with Rolling Stones Records, but Jagger passed, saying as many others had that the blues just doesn’t sell.

Millikin persisted. He persuaded his old friend Claude Nobs to book Stevie Ray Vaughan and Double Trouble to perform at the Montreux International Jazz Festival in Montreux, Switzerland. Nobs, who was the event’s producer, had never previously booked an unsigned act for the festival, but he trusted Millikin. On July 17, Vaughan and Double Trouble performed on the main festival stage. A handful of audience members in the front row booed, which greatly discouraged the band. After the set, they agreed to play an after-hours show in the artists’ lounge but canceled plans to play a second night.

Although the show didn’t seem to go all that well, it turned out to be the most important gig of Stevie Ray Vaughan’s career. David Bowie was in the audience, and he made a point of meeting Vaughan and his manager in the after-hours lounge. John Paul Hammond, the son of record producer John Hammond, also saw the show and asked for a tape of the performance to give to his father. Jackson Browne caught the band’s performance in the after-hours lounge, and he sat in with the group until early the next morning. Within the next few months, Browne invited Vaughan and Double Trouble to his L.A. studio to record a demo, Bowie asked Stevie to appear on his next album, and John Hammond, who helped develop the careers of Bob Dylan and Bruce Springsteen, helped the band sign a deal with Epic Records and offered to produce their debut album. The rest, as the cliché goes, is history.

Jackson Browne delivers the final word: “Blues was a long-standing pillar in most musicians’ lives, but it was not something that was going to make any bread. Blues had not been resurrected yet. Stevie Ray did that. He resurrected the really deep blues and roots music, took it to the altar and made it a serious thing. He introduced the blues to a whole new generation, and that was quite a stunning development.”