The hunt for alternative tonewoods: how guitar luthiers are looking to save the planet

In the second of this two-part report, we ask how luthiers are trying to do their bit for forests and creating a new generation of planet-friendly guitars...

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Where’s your next acoustic guitar tonewood coming from? In the face of ecological crisis and concerns over supply, acoustic guitar makers are shaking up their methods and materials.

In this, the second part of our report on the future of acoustic guitar woods, we ask what the next generation of acoustics will be made from.

Do makers keep going after the same revered species of wood? Protect and replant the ones we like the sound of? Search out lookalikes and use them up, too? Stand back and let forests recover while cooking up synthetic materials?

Or how about picking over our old waste – furniture, whisky barrels, railway sleepers? Spoiler: it turns out to be all of the above.

The 2017 trade clampdown on the rosewood (Dalbergia) species – and anything made from it – was a watershed moment in acoustic guitar land.

Although some makers did continue to parcel out existing stocks of prized woods, often on premium acoustic guitars, others walked away from rosewood and probably won’t be going back to it any time soon, even though instruments have now been exempted from the trade restrictions.

For some smaller outfits the additional paperwork required by the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) made shipping rosewood guitars too much of a headache.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

But major brands made significant moves, too: Fender announced as early as May 2017 that it was turning from rosewood to ebony and pau ferro fingerboards on its Elite and Mexican ranges respectively; and summer 2019 saw Martin’s 00- and 000-16E models feature granadillo back and sides.

If people like the forest then they should be careful about demonizing wood… grow it. Use it

Bob Taylor

The challenge of sourcing sustainable materials for guitars has been occupying Bob Taylor for years. The founder of US major Taylor Guitars is chipping away at it on a number of fronts – from scientific research to community replanting, to waste reduction and even tapping urban waste wood.

How do you know how sustainable your music wood is? If the question is how to be sure where it comes from, that it’s legal and harvested in a way that leaves forests and people who rely on them in reasonable shape, the answer is to be able to trust your supply chain and supplier. So third-party sourcing specialists, auditing, verification and certification – for example, through Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) – are all common approaches.

Alternatively, you can become your own supplier. As a co-owner in the Crelicam ebony sawmill in Cameroon (alongside Spanish tonewood supplier Vidal de Teresa of Madinter), Taylor has eyes on the entire supply chain of ebony from forest to factory. It’s also enabled him to tackle waste.

Most felled ebony used to be left to rot because it didn’t match consumers’ preference for jet black ebony. In fact, he says, a law passed in Cameroon in around 1910 made it illegal to bring to the port for export any ebony that wasn’t jet black.

Taylor has spent the best part of a decade challenging this mindset. Coloured ebony fingerboards and bridges now feature on Taylor’s own lines, and in Fender’s American Elite electric guitars and basses. Not everything works out first time. Taylor changed the Ebony Presentation series mid-stream to feature Tasmanian blackwood back and sides after it found the colored ebony would sometimes crack in a factory environment.

But, Taylor says, “many luthiers making bench-made guitars are having good success” and he’s confident that Lowden in Ireland and Furch in the Czech Republic will be using coloured ebony in their guitars. Erika Marinova of Dowina Guitars in Slovakia says, “We will use Taylor’s coloured ebony for sure. Not only is it from a sustainable source, it is extremely beautiful.”

To save ebony, we have to use it. If I quit using it, I’ll probably quit planting… the ebony will go away

Taylor has also started discussions with the piano industry about “what happens when jet black wood disappears off the menu. When it was abundant, of course you’d want to use black, but now it’s wrong to choose that and reject the other stuff. It’s just wasteful.” Taylor has even set up a company producing kitchenware from ebony that would otherwise “go on the burn pile”.

Alongside the Crelicam sawmill, Bob Taylor is personally funding The Ebony Project, which is researching the ecology of the species, the way it propagates and grows, developing high-quality strains, and working with a handful of communities in Cameroon to plant ebony saplings alongside fruit and medicinal trees.

“Ebony really needs a donor to pay some people to plant these trees,” says Taylor. “Then we all go away for 100 years and they own those trees. Hopefully their descendants will sell to mine.”

He’s anticipating a quicker return in Hawaii, where over the next eight years Taylor plans to plant about 180,000 koa trees on one property alone. The species is reportedly in tight supply right now after decades of heavy harvesting. But Bob Taylor says that “35 to 45 years from now, we’ll have a pretty sustainable supply of koa to go into guitars”.

A Cameroonian man tends to ebony leaf cuttings planted in non-mist propagators at his community-based nursery. This vegetative propagation technique can produce large numbers of trees.

Research technician Alvine Tchouga in the tissue culture lab at the Congo Basin Institute, where methods of ebony propagation are being studied.

Those may be distant horizons for the average maker or player. But Taylor’s view is that you need to keep growing high-value species in the forests longterm. “To save ebony, we have to use ebony,” he says. “Because if I quit using it I’ll probably quit planting and then I’ll just leave it up to the world and what the world does – and the ebony will go away.”

“I hope we’re always sourcing tropical woods, I hope we’re always sourcing temperate woods,” says Scott Paul, Taylor’s sustainability lead. “Because if we are that means those forests are functioning and healthy and there.”

Think Global, Axe Local

Even though temperate and boreal forests are under pressure – from climate change, fire, disease and exploitation – they may offer advantages over tropical woods for US or European makers and players.

For one thing, they can be nearer to hand – a plus if you’re looking to simplify your supply chain or reduce your timber’s travel miles.

In 2016, more than 30 luthiers took up the The European Guitar Builders’ Local Wood Challenge to make guitars entirely from local woods “to show that there need be no compromise in using non-traditional woods”, says EGB board member Adrian Lucas. “This can be seen as a return to tradition: until the Renaissance, all instruments were made from local woods and other materials.”

The idea is gaining ground. In a few years, the Local Wood Challenge has spread from its debut at the Holy Grail exhibition in Berlin to other shows in Europe and Canada.

If you know what you’re doing, you can make a pretty damn good guitar with most woods

Ervin Somogyi

Local isn’t the preserve of boutique luthiers. Godin is big: the brands within the group make some 200,000 guitars a year, and they will use 95 per cent Canadian woods such as spruce, maple and wild cherry. Riversong Guitars, also operating out of Canada, uses all Canadian woods.

And US builders don’t have to go far to get hold of Sitka or Adirondack spruces, walnut or maple – although there are worries about a beetleborne disease affecting American maple at present. Breedlove in the US uses the pale and interesting Oregon myrtlewood, while European makers such as Dowina and Lowden offer Dolomite and Alpine spruces among their tops.

“A temperate forest has way better governance and way better habits,” says Bob Taylor. “So we’re making a switch right now from mahogany to East Coast American maple. We have basically a sustainable supply. There’s maple forest that’s thick and dense and they plant those trees to make syrup. We’re starting to use that on our acoustic guitars and it could take half the pressure off our tropical American mahogany.”

Tom Sands, pictured left in his workshop, is a custom acoustic guitar builder based in North Yorkshire who studied under Ervin Somogyi in California.

Thoughts on salvage

If you want to avoid cutting down trees at all, how about waiting for them to fall down? In Hawaii Josh Johansen of KoaGuitarSets.com favors this kind of salvage over taking immature koa from intact forest.

“I don’t think we should be taking down young trees even if they are spectacular,” he told Tom Sands on The Interval podcast. “They are habitat for wildlife. They can grow and make seeds and when their time is done they fall and then me or someone like me comes in and carefully gets it out.”

Some of the Godin brands state that they only use wood from trees that have already fallen, with no clear-cutting involved. So if you play a Seagull, Art & Lutherie, LaPatrie cedar-topped guitar, or many with Simon & Patrick or Norman on the headstock, then there’s a good chance its top, back and sides have been produced in this way.

When city trees come down, they are typically disposed of at taxpayers’ expense, burned or used as mulch if you’re lucky. Some of this wood is music-quality tonewood

Bob Taylor

Alaska Specialty Woods, based in the Tongass National Forest, claims to be the largest producer in the world using locally procured “100 per cent salvage-sourced old-growth Sitka spruce”. This includes some music-quality trees that were used decades ago to build bridges, for example.

ASW says it supplies as many as 50,000 guitar tops a year to the industry, including Sitka, Western red cedar and Alaskan yellow cedar. Customers include George Lowden, who says, “We could use wood from freshly felled trees, but this needs to be greatly restricted today in order to preserve these ancient trees.”

Talking of ancient, custom builders love to use 5,000-year-old bog oak that’s been salvaged from UK farmland, or redwood sinker logs that have been lying in Californian rivers for decades.

These Taylor 600 series models (618e, left, and 614ce) include bigleaf maple back and sides, offering up a new way to consider maple as a serious alternative to rosewood and mahogany.

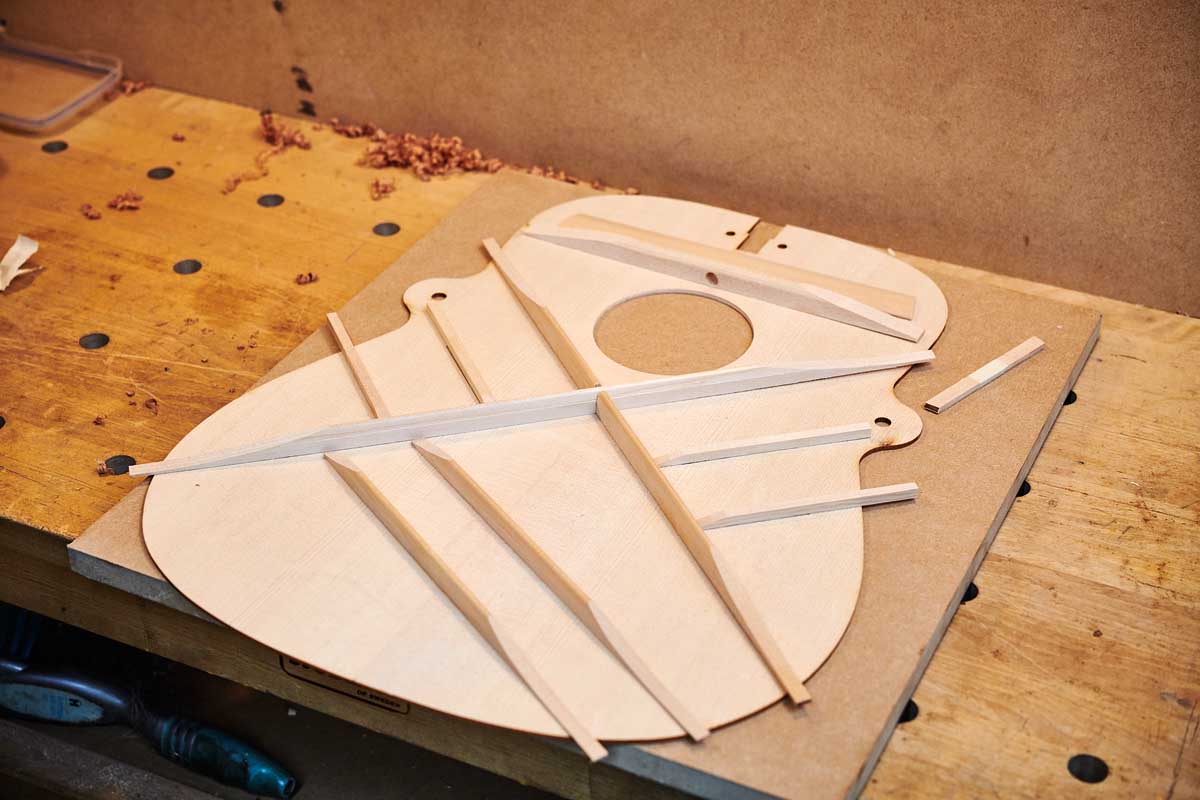

A Sitka spruce guitar top being prepared for final construction. Even once-abundant supplies of instrument-grade Sitka are getting scarce.

One of the hottest topics among environmentalists in recent years is rewilding – it’s even a storyline on The Archers. This is the idea that nature will thrive if we just leave it alone.

Even a fallen tree in a woodland is part of an ecosystem and removing it upsets the system. So perhaps the purest hands-off-the-forest approach is reuse – a mahogany piano lid (AJ Lucas Guitars) or a single-malt whisky barrel (Fylde), or a railway sleeper made of Alaskan Sitka recovered from a line in Vancouver, British Columbia (Tom Sands).

Most reuse tonewoods in this vein won’t be on the bargain rack. But in case you thought local upcycling was only for boutique luthiers, it turns out Bob Taylor is having a crack at this, too.

City Branch

“When city trees come down, they are typically disposed of at taxpayers’ expense, burned or used as mulch if you’re lucky. Some of this wood is music-quality tonewood. And every board foot taken from the urban wood dump is a tree not taken from a forest,” says Taylor. “There’s a tremendous amount of wood in that waste stream,” says his colleague Scott Paul. And tremendous variety.

“People just planted everything in cities – it’s amazing. We went to one location and pulled five or six different species and were just kicking the tyres, and virtually all of them are quite promising.”

An urban wood – possibly a tropical ash or eucalyptus – might appear on a Taylor guitar as early as a couple of years hence “because the trees aren’t coming from Fiji, Guatemala, Honduras, Africa, India – they’re coming from Los Angeles. It’s crazy,” says Taylor.

Let’s not think that next year buyers will be overwhelmingly putting pressure on guitar makers to deliver some level of sustainable guitars

The long-term approach could be about growing more trees in cities. Paul says cities globally are losing trees at a “staggering rate”. “If we are able to stabilise the urban canopy, it could help on a number of levels, from energy bills to mental health, fighting climate change and adding biodiversity.”

But is there already urban waste wood in Europe and America that could make a neck, for example? “I’m going to say yes,” says Scott Paul. “Is there enough to tap into a dedicated line? That is a great unknown because it’s a conversation that by and large is only taking place in North America right now – people looking seriously at the urban waste stream and trying to figure out how to tap into that, build local economies and take pressure off natural forests.”

It seems to be a conversation that Taylor is willing to kick off. Perhaps one day some of that red Chinese furniture blamed for the rosewood CITES listing in 2017 will find salvation as a guitar. Hongmu Series, anyone?

Hey, Buyer

Amid the brouhaha of the CITES rosewood clampdown, US luthier Michael Bashkin (check out his deep-dive podcast Luthier On Luthier) wondered whether guitar buyers are at last realising it’s time to move on from traditional tonewoods. We’re breaking down guitar-shop doors and demanding forest-friendly guitars, right? It seems not.

Yes, many guitar makers are beavering away on alternative raw materials, and retailers can often talk knowledgeably about whether this or that is responsibly harvested, and what that might mean – if you dig around their websites, or if you ask. But not many of us are asking. Or not yet enough to make forest-first, species-friendly acoustic guitars anywhere near the loudest show in town.

Which is a bit surprising when you consider how much of an inroad ethical shopping has made into things such as food and fashion, even nerdy stuff like investments and household energy tariffs. It’s also surprising when you consider how long we’ve known about the plight of the world’s forests. (It was before Sting.)

“Progress is being made,” says Bob Taylor. “But let’s not think that next year buyers will be overwhelmingly putting pressure on guitar makers to deliver some level of sustainable guitars. But I do think that next year more buyers will prefer to buy a brand that is actually doing something significant and is able to communicate that.”

Sustainable Alternatives: Reclaimed Wood

Recovering 5,000-year-old tonewoods from the bog

“Using reclaimed wood is rather more green and sustainable – for a small-production luthier – than even using local sustainable woods,” says UK guitar maker Adrian Lucas.

“You might have a wardrobe that comes to the end of its life, but the material it was made from is as good as the day it was built and it’s such a waste to discard the whole thing. “Reclaimed wood can be of a very high quality,” he continues, since moisture and chemical content may have stabilised.

Finding big enough pieces intact can be a challenge but “a four-piece back is every bit as good as a two-piece, and can often allow one to maintain quarter-sawn grain over the whole width”.

Because there is no oxygen in the mud there is no decay. Bog oak makes great fingerboards and its colour means it has quite a traditional appearance

Among the most alluring of salvaged woods, bog oak or Fenland black oak has been submerged in boggy ground for perhaps 5,000 years.

“Because there is no oxygen in the mud there is no decay,” says Lucas. “Bog oak is usually black and sometimes fades to brown, but the oak figure is still visible and can be very beautiful. It often turns up in fields where it is a nuisance to farmers. It makes great fingerboards and its colour means it has quite a traditional appearance, but it also works very nicely for acoustic back and sides.”

Lucas has made an Arbour model with entirely reclaimed woods apart from the bridge pins, purflings and rosette veneer: a soundboard of reclaimed 80-year-old Douglas fir; back and sides of Honduras mahogany from a chest of drawers; a mahogany neck made of a door frame from Bradford University; and an Indian rosewood fingerboard and bridge from an old dressing table.

Sustainable Alternatives: Man-made Materials

Dumping traditional tonewoods for engineered materials may be a step too far for some. But it’s an obvious area to explore.

California’s Blackbird Guitars produces completely wood-free instruments made from a “flax linen fiber and bio-based resin material” called Ekoa, which it says is lighter than carbon fibre, stiffer than fibreglass, stable under temperature and humidity changes, and offers “a better soundboard than spruce because of its superior stiffness-to-weight values”.

For individual components, the wood fibre-based composite Richlite, approved by the Forest Stewardship Council, Rainforest Alliance and Greenguard, is already familiar as fingerboards and bridges on, for example, Martin’s Mexican-made guitars.

Rocklite, meanwhile, is a blend of American tulip and European eucalyptus, says its UK developer Steve Keys.

Luthiers in Sweden have been early adopters, in the US Michael Bashkin uses it, and it’s finding fans among young British luthiers, too, including Tom Sands who says it looks like wood, has a tap tone like wood, and works like wood.

“You plane a fingerboard, you get shavings and curls coming off just like ebony.” Listen to Sands and Keys in conversation on The Interval podcast.

Bob Taylor is a fan of wood. “I do lend hope to some woods that are being modified, and if the growth in that business sector continues, I can imagine some modified woods being blended into guitars.”

But he adds, “If people like the forest then they should be careful about demonising wood. If we simply decide to abandon certain wood species it’s not like forests will be left alone. They’ll surely, absolutely be converted into other uses. Let’s just grow wood. It grows on trees. Grow it. Use it. Grow it some more.”

Gibson's Sustainable Series

Gibson's environmentally minded efforts

Gibson’s 2019 offered includes the Sustainable series, which the company described as “built with the environment in mind”. Based on the J-45, L-00 and Hummingbird body shapes, the series incorporates Alaskan Sitka spruce tops, North American walnut, Central American mahogany necks and Richlite fingerboards and bridges.

Robi Johns, sales and marketing director for Gibson Acoustic, says the spruce and walnut are from “sustainable sources, and we expect them to be around for many years to follow”. On top of Richlite’s eco-credentials, he says it also provides the right black background for maple inlay.

“The Sustainable series was created for us to march forward as a responsible wood user,” says Johns, and to appeal to “consumers looking for a more natural instrument, an earthy kind of instrument”.

Johns says the Sustainable series has sold in its hundreds, but that it’s a little early to tell if it’s going to continue.

The group recently launched what chief merchant officer, Cesar Gueikian, referred to as the “Gibson Lab”, where they would be “testing how we evaluate our standards for our partners who are sourcing wood, and what are the different woods and alternatives that we could be using.”

Martin and Sustainability

How Martin Guitars is utilising alternatives to the traditional tonewoods

“Mother Earth will be cheering you on,” says Martin, if you pick up one of its Forest Stewardship Council (FSC)-endorsed acoustics.

There are currently two of Martin’s 150 or so models that carry the FSC stamp, meaning all materials in an instrument have been judged to meet the organisation’s forest management standards.

At one end of the FSC range, the OME Cherry features a Sitka spruce top, cherry back and sides, mahogany neck, ebony fingerboard and bridge, plus African blackwood headplate.

The most expensive in the range, the 00-DB Jeff Tweedy is Martin’s first Custom Artist model certified by the FSC and carrying the Rainforest Alliance seal. Mahogany top, back, sides, neck and headplate, and Richlite fingerboard are all FSC certified.

Richlite also appears as fretboards and bridges on the X, Road and the Junior series. Martin’s sourcing specialist Albert Germick says engineered materials are “always something we’re looking at”.

“When the CITES thing occurred,” says Germick, “we started looking at more alternatives to rosewood and we did decide to use granadillo (Platymiscium yucatanum) and katalox (Swartzia cubensis),” which he describes as “sustainably harvested”. The Martin 00- and 000-16E, launched in 2019, feature granadillo back and sides.

At its Mexican plant, the company has been switching necks from mahogany to laminate birch from the US, and uses HPL (high-pressure laminate) on its X and LX lines, “greatly reducing our consumption of mahogany and rosewood”.

Martin says it is planting koa in Hawaii, mahogany in Nicaragua, cocobolo and mahogany in Costa Rica, and is in a partnership to replant maple in Pennsylvania.