The life and times of Johnny Thunders: the New York Dolls and Heartbreakers guitarist who crystallized the essence of street-cool rock ’n’ roll

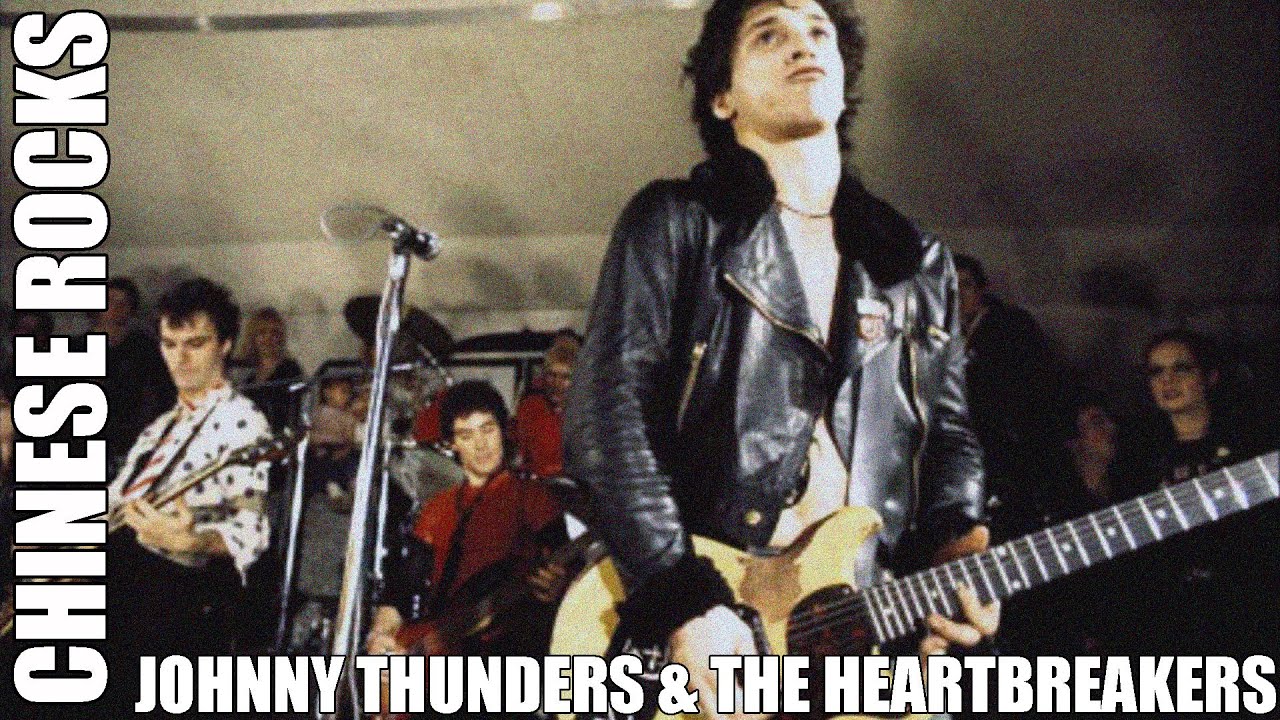

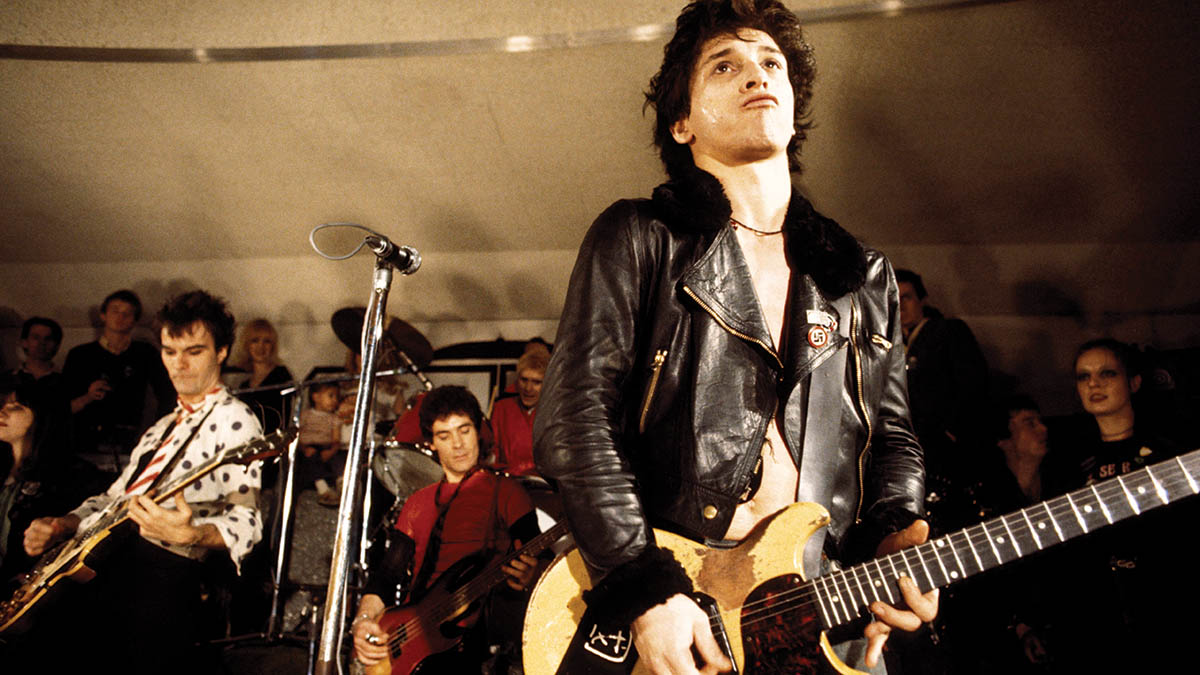

Brilliant, self-destructive, hugely influential, Johnny Thunders was a voice of nature who made helped make the TV Yellow Les Paul Junior one of the coolest electric guitars ever

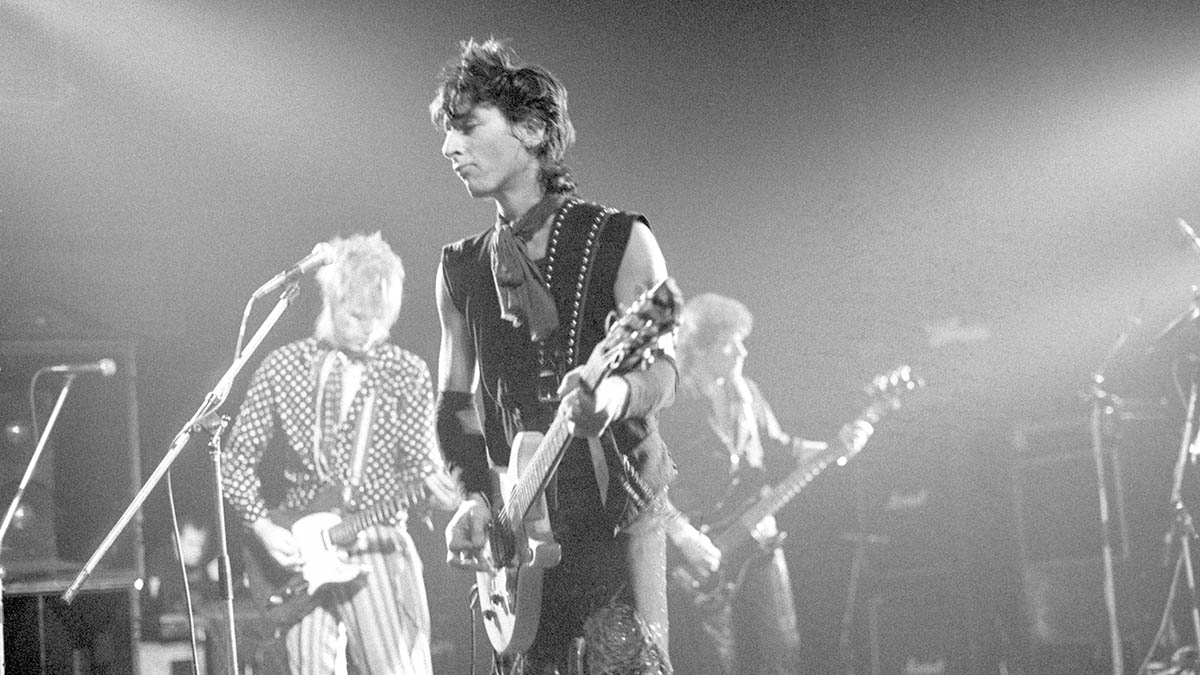

The first time I saw Johnny Thunders – with the New York Dolls on U.K. TV in 1973 – I immediately connected with the reckless abandon that was apparent in every gesture, every guitar-hero pose he struck.

And then there was the rawness of the band’s approach at a time when mainstream rock was still mired in the keyboard-laden pomposity of prog and the tired blues-rock tropes that had become the standard fallback for many so-called “serious” bands of the time.

As a huge fan of British glam rock, particularly T. Rex and Slade, here, at last, was an American band unafraid to transcend the predictable and the expected, to deliver their own brand of shock rock ’n’ roll. Even 50 years later, when taking a solo, if in doubt, I’ll ask myself, “What would Johnny Thunders do?”

The mystery is why Thunders remains relatively uncelebrated, yet the artists who have admitted his influence dominate modern rock music. It’s time to address Thunders’ legacy and restore him to his rightful place in the pantheon of rock ’n’ roll.

Thunders was the embodiment of the “live fast, die young” guitar hero mythology. With his low-slung Les Paul Junior, leather jacket and shock of black hair, he became an instant cultural icon when the New York Dolls started to attract attention.

Unfortunately for Thunders, addiction issues dogged him from the early ’70s; while fellow Heartbreaker Walter Lure managed to kick the habit in the late ’80s, Johnny was never able to do the same and was to meet an untimely end in a New Orleans hotel room in 1991. The cause of death? It was officially an overdose, but mystery surrounds the details.

The huge influence of Thunders in particular, and the New York Dolls and the Heartbreakers, is apparent from the legions of fans who’ve gone on to form successful bands, citing the mystique of Thunders as a prime motivator in their own desires to forge a career in music.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Born John Anthony Genzale in Queens, New York, in 1952, Thunders formed his first band, the Reign, when he was 15. By the time he was 17, he was a familiar face at shows around NYC and was even to be seen in the audience at a Rolling Stones show at Madison Square Garden, captured forever in the 1970 film Gimme Shelter.

Spotted by future New York Dolls Sylvain Sylvain and Billy Murcia, who were instantly drawn to his street-cool image, they invited Thunders to join their band, the Dolls, in 1970. Sylvain didn’t care whether Thunders could play or not – it was the image that mattered most. Recruited to play bass, under Sylvain’s instruction, Johnny soon figured out that the lead guitarist gets the girls and the glory; he insisted Sylvain teach him how to play guitar.

Sylvain didn’t care whether Thunders could play or not – it was the image that mattered most

The Dolls fell apart after about six months, and Thunders joined bass player Arthur Kane’s band, Actress, which quickly recruited Murcia. Thunders was now playing guitar and singing. Demos were recorded, with many of the songs to resurface under different titles in future New York Dolls and Heartbreakers sets.

Allowing for the poor sound quality, the raw power was already clearly apparent, with Thunders’ distinctive voice bringing a unique mix of excitement, sensitivity and edge to the songs. For all the digs at the NYD’s musical chops, the musicianship, writing and arranging skills displayed on the demos reveal a band overflowing with confidence, panache and an unshakeable faith in their own talents.

After a few months fronting the band, Thunders decided he no longer wanted to sing, and David Johansen was recruited. The lineup was completed with the return of Sylvain, and the re-christened New York Dolls played their first show in December 1971.

Becoming regulars on the NYC club scene, particularly Max’s Kansas City, the Dolls were often chaotic live, but by 1972, they had already become a major influence on many of the acts that would go on to form the NYC punk and new wave scene.

Even Kiss’ Gene Simmons and Paul Stanley took in shows by the band, although ironically, they drew their inspiration from their belief that if the New York Dolls could do it, anybody could.

There were many New York bands who clearly aspired to an intellectual artiness, but the Dolls approach was, “Fuck art – let’s dance”

New York was a down-and-dirty city in the early Seventies, and the New York Dolls were the perfect embodiment of that, with Thunders appearing particularly feral at times. There were many New York bands who clearly aspired to an intellectual artiness, but the Dolls approach was, “Fuck art – let’s dance.”

Thunders already had the wise-ass street attitude down pat, as the late Alan Merrill recalled in a discussion about Thunders: “I can remember an encounter with him at a 48th Street and Broadway guitar shop in 1972. My band mate, Jake Hooker, was trying out a Les Paul. Thunders came up to him and said, ‘You sound pretty good, man.’ Jake looked up and said, ‘Thanks.’ Then Johnny lowered the boom and said, ‘How long have you been playing guitar, two weeks?’”

As interest in the band started to build, with press interest in the States and overseas, in 1972 they managed to snag an invite to support Rod Stewart and the Faces at Wembley Stadium in England, followed by shows around the U.K. – huge exposure, having only previously played club dates in New York.

Even more surprisingly, the band scored a spot on The Old Grey Whistle Test, the only U.K. rock music TV show at that time, lip-synching to Jet Boy. The show’s host, British radio legend Bob Harris, dismissed them derisively as “mock rock” when the song ended. That may have been one of the key triggers in the early swellings of the U.K. punk movement – you either got it or you didn’t, and Harris clearly didn’t.

When I saw the Dolls I thought they were outrageous, dangerous, sexy and a mess all rolled into one

Mick Rossi

Mick Rossi, from first-generation U.K. punks Slaughter and the Dogs, remembers watching the show: “I would zone in on anything exotic; I loved Mick Ronson, David Bowie and Marc Bolan. When I saw the Dolls I thought they were outrageous, dangerous, sexy and a mess all rolled into one.” [Laughs]

Sylvain recalled Harris’ comment in an interview shortly before his death in 2021. “We had to mime to an edited version of Jet Boy, and we really didn’t do that as a band normally. I guess if we’d played live, he might have had a different take, but ya know, I suppose, fuck you, Bob!”

As was typical of the Dolls, and indeed Thunders’ career, triumph quickly turned to disaster while in the U.K., when Billy Murcia died, aged 19, from a fatal Champagne-and-pills combo. Returning to America, the band’s stock had risen, having toured in Europe, and ironically, they also benefited from the shock of Murcia’s death by enhancing their dangerous and wasted vibe.

Continuing to generate interest and a rabidly loyal hardcore following from their live shows, in 1973 they managed to snare a record deal with Mercury, releasing their self-titled debut album the same year, with Todd Rundgren handling the production.

The cover shot of the band, sporting full makeup, looking like transvestites from Mars, was too much for American audiences; but across the pond in the U.K., glam rock was huge at that point, with many of the bands looking even more outrageous than the Dolls.

The U.S. was totally unprepared to embrace the Dolls’ brand of androgyny, which was the reason so few of the British glam acts were to enjoy success Stateside, even though they were selling millions of records everywhere else in the world.

There was to be one more NYD album, the prophetically titled Too Much Too Soon, released in 1974, with a similar mix of songs to the first album and a live cover shot of the band, which perfectly captured the unpredictable excitement of a great Dolls show.

Sales were poor and they were dropped by Mercury. Without a label, and with the band starting to pull in different directions, Thunders and Jerry Nolan, Murcia’s replacement on drums, left to form the Heartbreakers in 1975.

Richard Hell, the original bass player, was replaced by Billy Rath when Hell went on to form the Voidoids. The iconic lineup was completed by the addition of Walter Lure to share guitar and vocal duties.

I grew up loving Chuck Berry and Keith Richards – they were two of my biggest influences, and to me that’s what Thunders was

Steve Conte

The music the NYDs had made was a celebration of everything they’d grown up hearing on the radio, with elements of ’50s rock ’n’ roll, blues and Sixties girl groups, the same basic formula that informed Thunders’ work for the rest of his career.

His guitar style was already fully formed on the Actress demos – a raw, urgent combo of Chuck Berry and Keith Richards, cut with Thunders’ distinctive glissandos. Steve Conte, who took Thunders’ place in the reformed New York Dolls, expressed the same view: “I grew up loving Chuck Berry and Keith Richards – they were two of my biggest influences, and to me that’s what Thunders was – a combo of those two, which made it real easy to fit into the band at that time.”

Johnny’s weapon of choice, the Les Paul Junior in TV yellow, was the perfect axe – minimal, direct and cut-through with the essence of rock ’n’ roll – basically the blueprint for Thunders’ own ethos. That guitar became an object of desire for the Cult’s Billy Duffy: “I lusted after his TV yellow Les Paul Junior. [Laughs] I finally picked up my own Les Paul Junior in 1979, though it was a wine red one. I couldn’t find a yellow one in England at that time!”

The combination of the Junior and a Twin Reverb, cranked to the max and with a ton of reverb was what rock ’n’ roll should sound like

Mick Rossi

Rossi remembers his band supporting the Heartbreakers on a number of U.K. dates: “The sound he got was so uniquely his; the combination of the Junior and a Twin Reverb, cranked to the max and with a ton of reverb was what rock ’n’ roll should sound like. He was a lovely guy; my amp was crap at that time, so Johnny generously let me use his on our dates together.”

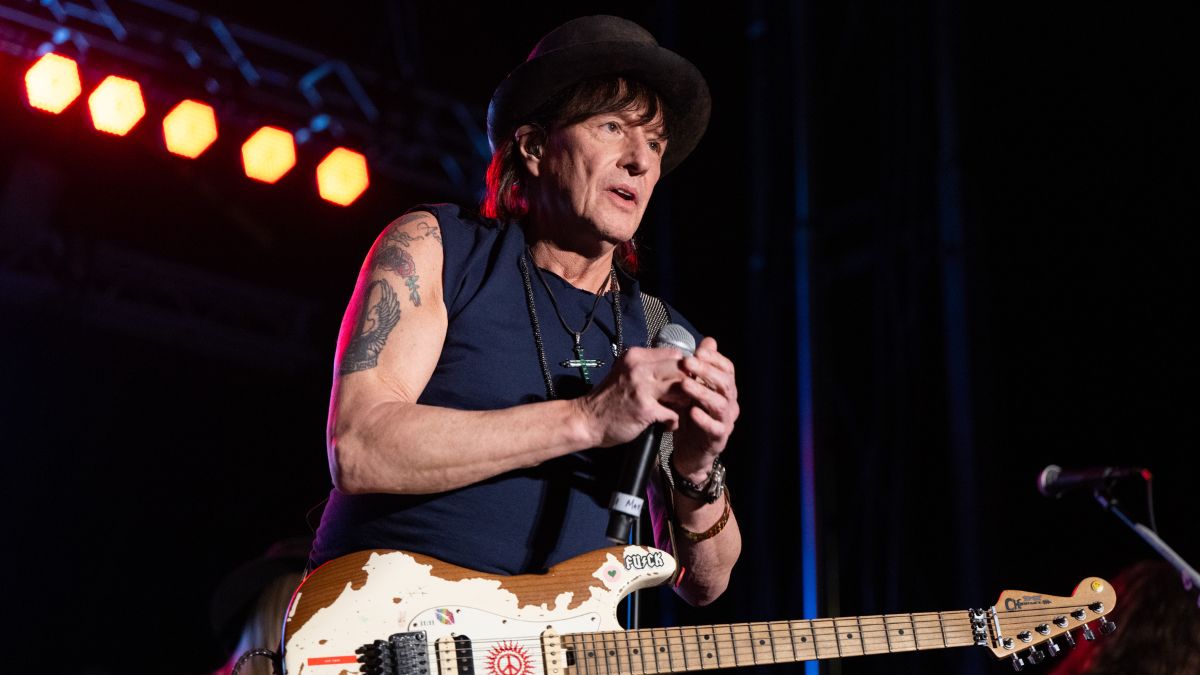

Rossi toured for three years with Lure’s LAMF Band, from 2017 until Lure’s death in 2020, and is now fronting Mick Rossi’s Gun Street (with an album due this year). During this period, he got an extra insight into the two-guitar dynamics of the Heartbreakers, replicating Thunders’ role every night on tour.

“Walter loved to tell stories about Johnny. You could tell he really admired him as a musician and as a person, in spite of Johnny’s chaotically unpredictable nature. Many of Johnny’s solos were so perfect that you just had to reproduce them exactly as they were on the records.”

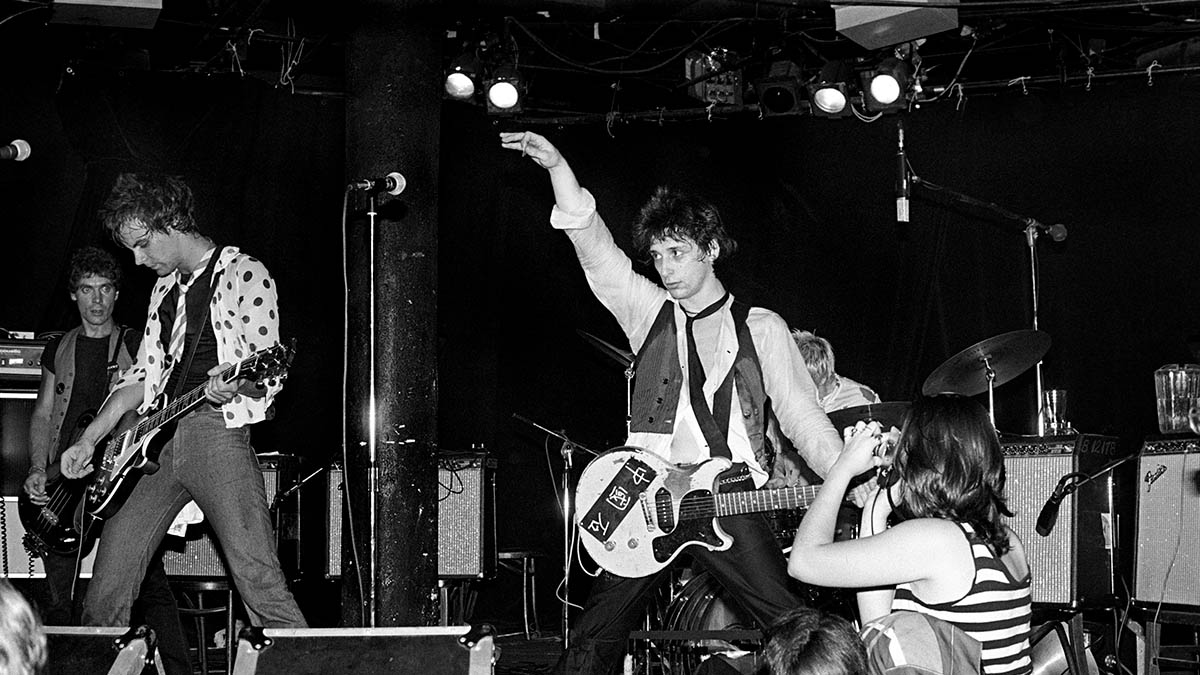

The Heartbreakers’ music was a tougher version of the Dolls’ sound; Thunders and Lure shared the spotlight out front, each usually soloing on, and singing the songs, that they wrote. In Lure, Thunders had found the perfect foil, bringing a sense of stability to Thunders’ chaotic live appearances.

The Heartbreakers had amassed a set of killer songs that sounded simultaneously old and new. In 1976, when all around were preaching the message of nihilism, destruction and boredom, the Heartbreakers were unafraid to sing songs about love and girls (and, on a couple of occasions… drugs).

With the U.K. punk scene ready to burst, the Heartbreakers were invited to appear on the ill-fated Anarchy tour in 1976, with the Sex Pistols and the Damned. On the day the Heartbreakers arrived in the U.K., Pistols’ frontman Johnny Rotten and Steve Jones had outraged a nation of TV viewers by engaging in an exchange with the show’s provocative host, taking the bait and calling him a “Fucking rotter” (and a couple more insults) on primetime TV.

As hard as it is to believe 45 years later, the uproar led to the cancellation of the vast majority of the U.K. dates.

With the band living in the U.K. in 1976, where they were to remain for a couple of years, Thunders’ self-sabotage streak reared its head when Jerry Nolan mooted the idea of renaming the band the Junkies.

Thunders was pressing hard in support of the idea, but Lure knew it would be commercial suicide; “We could have only done that if we were actually not junkies. Anyway, a record company would never have accepted it. Johnny liked the idea of pushing things as far as he could sometimes.”

The Heartbreakers had arrived in the U.K. as punk royalty, largely on the back of Thunders’ reputation and a British love for the music of the Dolls that they’d never experienced in their hometown. The Heartbreakers had no equal as a live act when they were on fire.

L.A.M.F. received mixed reviews but stands out as one of the few albums from the punk era that sounds as valid now as it did when it was released

Their incendiary live shows led to a contract with Track Records, and their only studio album, L.A.M.F., was released in 1977. Plagued by a muddy mix, the album received mixed reviews but stands out as one of the few albums from the punk era that sounds as valid now as it did when it was released.

Playing out like a stack of singles, every song hit the mark, with Thunders and Lure trading solos and riffs; many of the songs came in at under three minutes, not a wasted moment on the record. The lack of hard politicization, so prevalent at that time in many of the contemporaneous punk bands, removed the time capsule element of other artist’s albums, leaving it to stand as a timeless classic.

L.A.M.F. was as influential for its cover shot as it was for its music. Says Duff McKagan: “I remember, when I was about 15, looking at the cover, thinking the Heartbreakers were the coolest motherfuckers. In fact, I’d say their style still influences me and plenty of others even now, 40 years later.”

Michael Monroe, former singer for Hanoi Rocks and now working as a solo artist (his new album, I Live Too Fast to Die Young, is out now) remembers: “That was such a cool album cover; the image was for real, almost like a gang of wasted junkies – catch them while you can. It was real New York street stuff.”

I’d say their style still influences me and plenty of others even now, 40 years later

Duff McKagan

The sound problems that plagued the album began to frustrate the band, desperate to get the record released, and under pressure from Track to have it in the stores for Christmas. It seems like all of the band had a hand in trying to get the sound right, but to no avail.

Walter Lure: “We’d been listening to it for many months. The problem was that whenever we listened to it in the studio, on the tape, it sounded great, but whenever we pressed it onto vinyl, it lost all the brightness. We must have mixed it a hundred times – that wasn’t the problem, but Jerry felt like it was, and [he] ended up leaving the band in frustration. I think it was a mastering issue that did it.”

Nolan’s departure upset the chemistry in the band, and Thunders left six months later in 1978, to pursue a solo career. So Alone, the first fruits of his solo direction, received fantastic reviews and sold relatively well.

Among the list of guests in the studio were Steve Marriott, Chrissie Hynde, Thin Lizzy’s Phil Lynott, Wilko Johnson from Dr. Feelgood and Steve Jones from the Sex Pistols. The record featured one of Thunders’ most enduring songs, the melancholy You Can’t Put Your Arms Around a Memory, later to be covered by McKagan and Monroe on their respective solo albums.

Monroe: “Although people might think we were influenced by the New York Dolls, I think musically we were more influenced by the Heartbreakers. We even took our name from the song Chinese Rocks just making it Hanoi instead.”

Without a permanent band by 1981, Thunders recruited former Generation X bass player Tony James for a series of dates in Europe. James remembers the chaotic times: “Johnny just turned up at my door with Jerry Nolan and asked if I wanted to play with them that night!

Obviously the answer was yes, a dream come true for a Dolls and Heartbreakers fan.” James saw the unpredictable side of Thunders when, later that night as the band were waiting over two hours for him to arrive: “Three friends carried Thunders, unconscious, into the dressing room and proceeded to revive him for the show.”

For all the bad things, turning up wasted, missing shows, etc., there was the other side – a sweet, funny, uncompromising person

Tony James

The common theme in every story from people who knew Thunders was that he was, in spite of the public perception, an extremely caring guy who would go out of his way to help a friend.

James remembers, “For all the bad things, turning up wasted, missing shows, etc., there was the other side – a sweet, funny, uncompromising person.”

Monroe agrees: “When I finally got to know him and we became friends, I realized he had a heart of gold. I shared an apartment with Johnny and Stiv Bators in London in 1984, just after our drummer in Hanoi Rocks got killed in a car crash in L.A. As you can guess, there was never a dull moment. [Laughs] Johnny loved to sit around playing acoustic guitar and writing songs.”

So Alone should have reset Thunders’ course and brought him to the level of acclaim that he deserved, but his drug use was beginning to have a detrimental effect on his ability to manage the practical aspects of keeping a band on the road and maintaining his career.

There was more great music to follow, but the momentum that should have been generated by the profile-raising response to So Alone became lost. Permutations of the Heartbreakers would still reform sporadically for a handful of shows. Lure: “We’d often do shows because the money we could get going out as the Heartbreakers was much better than any of us could get in our own right.”

Thunders recorded a couple more great albums, Que Sera Sera in 1985 and Copy Cats in 1988, a collection of duets on classics with Patti Palladin. The state of Thunders’ catalog was as disorganised as the lifestyle he was leading, with numerous official, semi-official and unauthorised albums constantly turning up.

The vast majority were live recordings and many were of bootleg quality. Thunders got his own back on the bootleggers by compiling a set of albums capturing the best of the bootlegged shows and naming it Bootlegging the Bootleggers.

By the ’90s, Thunders’ career as a recording artist had stalled, with only the never-ending stream of live albums turning up in record stores. Live, Thunders was still a great draw, although given the parlous state of his health in the latter years of his life, there was sometimes an element of macabre voyeurism about the live shows.

As if his struggle with addiction wasn’t debilitating enough for him, he developed leukaemia toward the end, something he never revealed, but which came to light after his death. Thunders had started to look worryingly unwell, and presumably the disease played its part in his demise.

Given Thunders’ adherence to the “school of Keef circa 1970,” he spent a lot of time looking to score and running the inherent risks that incurred. Lure summed it up succinctly: “Johnny couldn’t survive without drugs, indeed they actually defined him, in his own mind anyway.”

Had Thunders lived, it is tempting to wonder what direction he may have gone in. A Heartbreakers reformation, perhaps?

Lure again: “I really doubt it would ever have happened. John never really wanted to reform – he really needed to be in control. Unfortunately, as long as John was on drugs, he couldn’t play to a consistent level and he could never quit the drugs. That being said, I think he was a genius, a maverick.

“I was probably a better guitarist technically, but Johnny had instant identifiability, something that I guess I never had. Being a drug addict myself back then, I know how hard it was to get clean. I didn’t get out of that mess until early 1988. Ten years wasted on that stuff.”

While the legacy of Thunders is clearly apparent across the spectrum of loud, wild rock ’n’ roll, with many acts not even realizing they are indirectly channelling his spirit.

Perhaps the reason that the mainstream still doesn’t acknowledge his significance is tied up in the thorny issue of the glorification of junkie culture, and the fact that for many, with only a superficial knowledge of his work, the drug stories always stole much of the oxygen from the music.

Monroe: “He was just too cool to be in the mainstream; he didn’t really care about fame. He had chances to do things to be a bigger name, but that was never what Johnny was about; success for him was to do things on his own terms. He never wanted to play the music business game, he was about the art.”

Thunders crystallized the essence of street-cool rock ’n’ roll. The drugs, the craziness and the chaos are all irrelevant, what matters is the music, and the music that Thunders created speaks for itself. The rock cognoscenti have always been hip to the magic of Johnny Thunders. Widespread recognition is long overdue.

Mark is a freelance writer with particular expertise in the fields of ‘70s glam, punk, rockabilly and classic ‘50s rock and roll. He sings and plays guitar in his own musical project, Star Studded Sham, which has been described as sounding like the hits of T. Rex and Slade as played by Johnny Thunders. He had several indie hits with his band, Private Sector and has worked with a host of UK punk luminaries. Mark also presents themed radio shows for Generating Steam Heat. He has just completed his first novel, The Bulletproof Truth, and is currently working on the sequel.