“I was so frustrated that I kicked my amp – the speaker busted, leaving me with this weird buzzing sound. I didn’t know it then, but I helped create the sound of punk-rock guitar”: How an Italian immigrant shaped the sound of US punk to come in the 1960s

Known as the godfather of punk guitar, The Standells’ Tony Valentino was one of the first guitarists to use Vox amps, and, in a fit of rage, created a guitar tone that would be emulated the world over

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

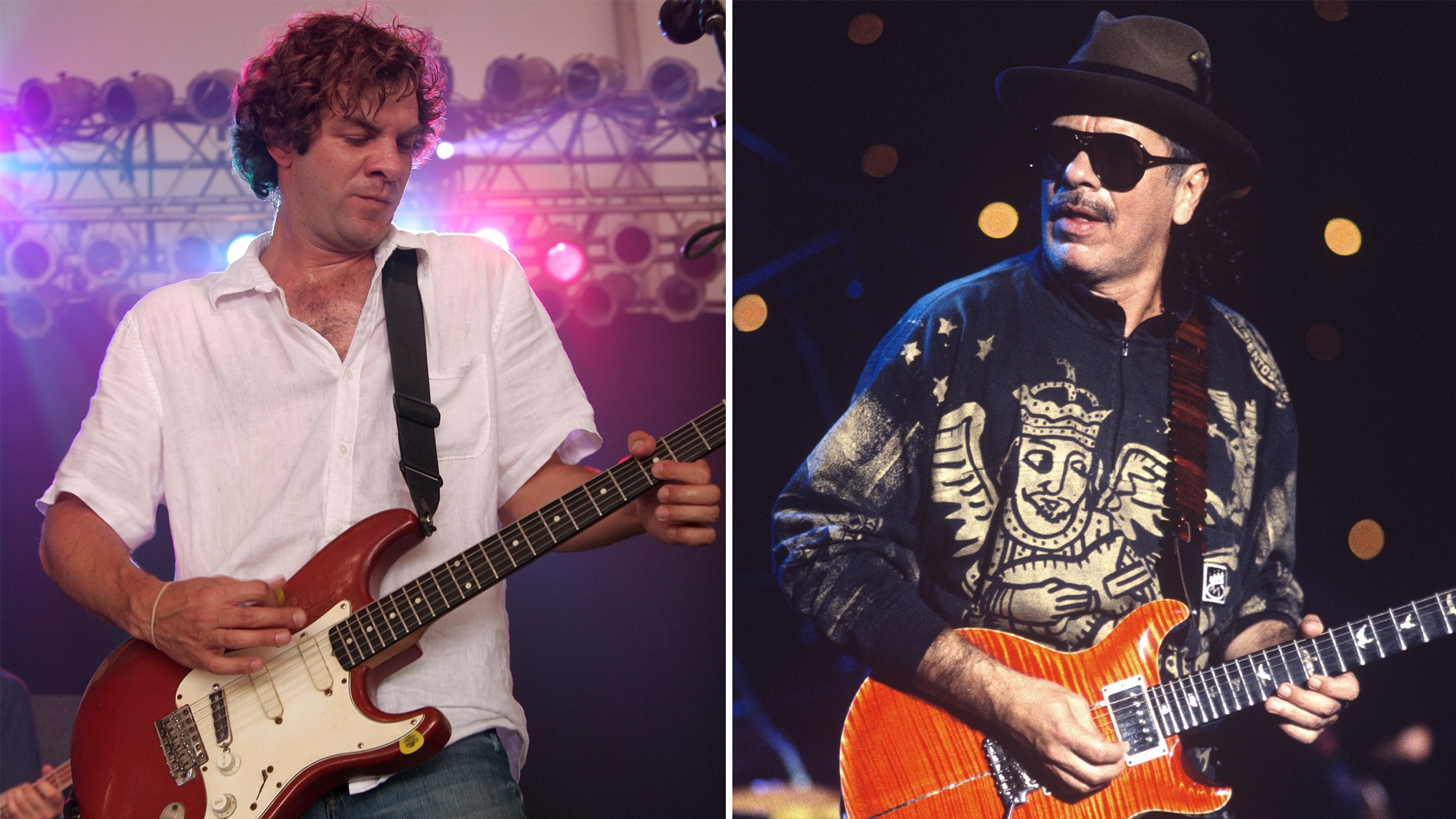

As a '60s garage rocker, The Standells' Tony Valentino brandished his dream guitar – a Fender Telecaster – and paired it with a Vox AC30, creating a sound that would become synonymous with late '70s punk rock, leading to Valentino occasionally being dubbed “The godfather of punk”, alongside Iggy Pop.

Before he could do that, though – as an immigrant from Italy suddenly immersed in early rock 'n' roll – Valentino paid his dues in the most budget-friendly way possible.

“When I got to the United States in ‘60, I had nothing, and I eventually got a Silvertone,” Valentino tells Guitar World. “But first, my friend gave me a no-name guitar, and I initially used it to play Italian music, which is different from American music – especially at that time.”

“What I was playing was nothing like rock 'n' roll,” he continues. “But I listened to the radio, and eventually that led me to keep messing with that guitar I was given and start to develop as a player.”

As for that Silvertone – which Valentino would unknowingly use to spearhead a movement – it came at a time when he was beginning to develop a case of Fender-related G.A.S., which Valentino laughs at, saying, “Once I started playing more, I went to Sears and got a Silvertone guitar. I didn't like it much and was so mad about it, but I couldn't afford a Fender! But I was happy that I could make some noise and play rock music.”

Soon, Valentino traded that Silvertone for a '50s Broadcaster and then, his beloved Fender Telecaster. With the Tele in hand, he and bassist Jody Rich formed The Starlighters, who morphed into The Standells.

Though The Standells' moment in the sun was brief – by way of the 1966 hit, Dirty Water, which made it to No. 11 on the Billboard Singles Chart – Valentino's influence was significant.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Years later, teenagers across the globe began channeling the nothing-but-the-basics, DIY approach of mid-'60s bands like The Standells. Valentino was unaware of these developments, until those same teens – who developed a sound that would come to be known as punk rock – began name-checking him.

When reminded of his 'godfather' status, Valentino smiles wide, saying, “I was hot-rodding guitars before there was such a thing! And we were writing punk licks before punk started. But when they started calling me 'The godfather of punk,' I didn’t know what to think, because everything I did happened by mistake.”

Considering his significance to the development of the punk guitar sound, one might assume that, in retrospect, the now 82-year-old Valentino considers himself a punk player. But it's not that simple. “I've played like this all my life,” he says. “And I'm self-taught, so what can I say?”

He continues, “Kids always ask me, 'Tony, how do you get that sound?' and I honestly don't know. It sounds corny, but it's just what comes from inside of me. Some people are born to be guitar players. When I play a solo, or a riff, I play it how I know how. So, if it's punk or garage – I don't know – I just play how I was meant to, and it's a style that became famous.”

As I understand it, a big part of your early sound came from a kicked-in amp. Is that true?

“It is. I was so mad that all my friends had Fender guitars and amps, and all I had was this cheesy Silvertone guitar and a cheap Sears amp. So, one day, I was particularly frustrated, so much so that I kicked the face of that Sears amp in [laughs].

“I kicked it, and the speaker busted in, leaving me with this weird buzzing sound, unlike anything I'd ever heard. I didn't know it then, but I helped create the distorted sound of punk-rock guitar. I stuck with that amp until ‘62 when I got my first Fender amp and a real Telecaster, which I'd always wanted.”

Tell me about the formation of The Starlighters, which eventually became The Standells.

“When I first arrived from Italy, I couldn't speak English and got a job in a bakery making bread. I quickly learned that I was allergic to whatever flour they were using, so I got moved to the oven department, which consisted of shoveling bread in and out of giant ovens [laughs].

“There, I met a guy named Jody Rich, who played bass, and we became friendly and eventually formed The Starlighters after he learned I played guitar. We used to practice in my garage, but not a lot was happening. But we did write the song Let's Go (Pony), which most people credit to The Routers, who ended up recording it with The Wrecking Crew and having a big hit.”

Before Let's Go (Pony) was a hit for The Routers, you and Jody recorded the demo, right?

“Yes, that's true. We got the idea for the song after attending a football game in Burbank, California, which is funny because it became a big hit at sports games. Jody and I did the demo together, and I used that Telecaster I mentioned before, which, now that I think of it, was a '50s Broadcaster. They later gave the credit to Lanny and Robert Duncan, but Jody and I wrote that song and did the original demo.”

After that, what was your vision for The Standells, from a guitar-related perspective, going in?

“When I came to America, I heard all kinds of songs by Richie Valens, Buddy Holly, Bill Haley, and guys like that. I know Buddy used a Strat, and I wanted one so badly but couldn't afford one. And then I wanted a Telecaster, but couldn't afford that, either! So, when I finally got a Telecaster, my idea was to create sounds that were less raunchy and different from typical Fender sounds, which were very punchy.”

Did you have a plan in place to make that happen?

“I wanted something cool but a little softer and less punchy. I'd play notes, get that Fender sound, and think, 'How can I soften this up?' I'd experiment, and I had a breakthrough once I got a Fender Super Reverb amp.

“My brother was an electrical genius, and he rigged up my old kicked-in Sears amp and got it linked into the Fender, and once that was running through each other, I got this crazy sound, like a distorted sound that was less punchy, softer, but still distorted. It's hard to explain, but I'd never heard anything like it.”

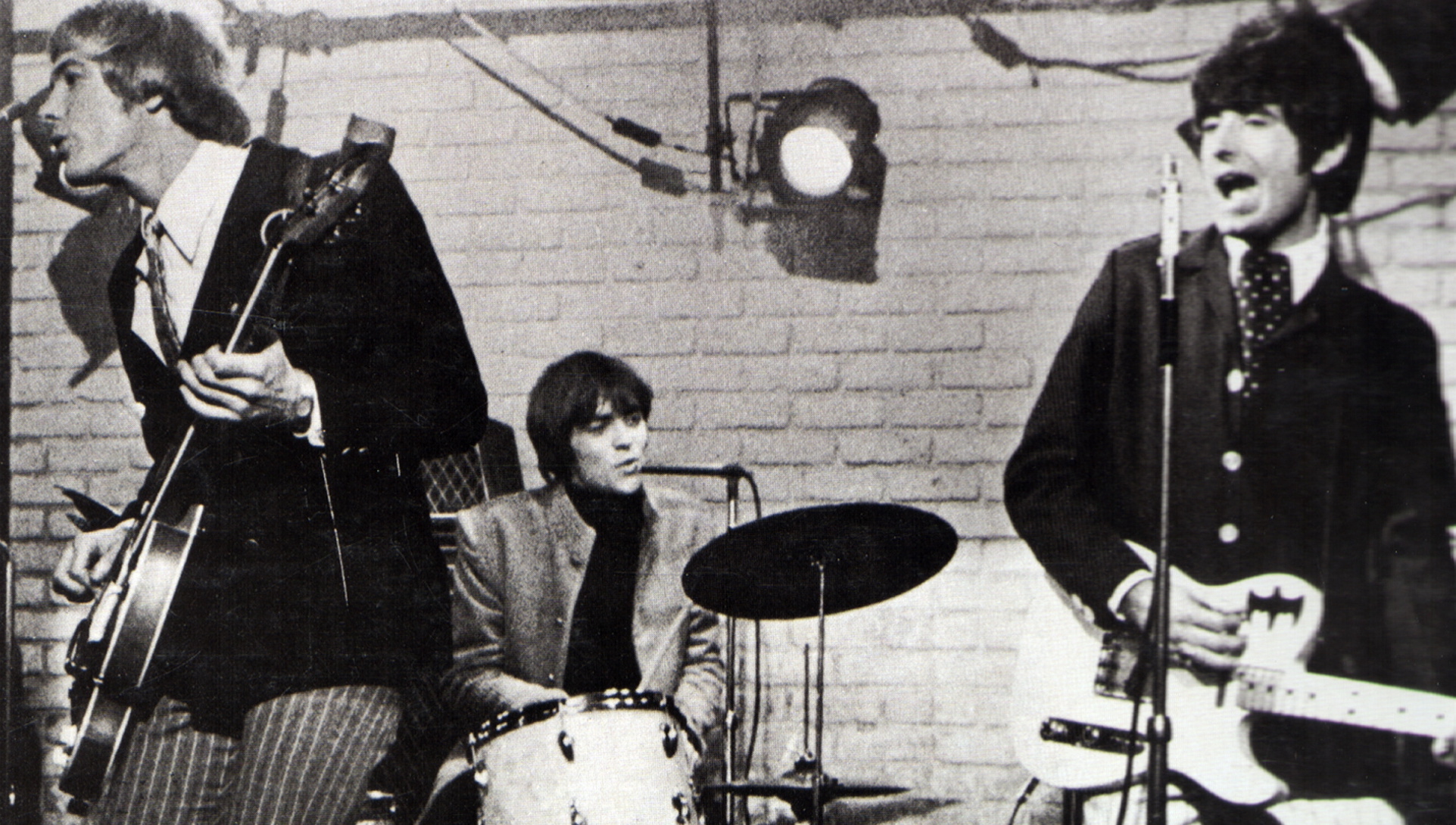

They wanted The Beatles, so the deal was that if The Standells were going to be on The Munsters, we had to dress like them and do I Want to Hold Your Hand

And when did Vox amps come into play? I know you used them in the studio later with The Standells.

“After experimenting with the Sears and Fender amps, The Standells got to go to Hawaii to play some shows, and we started to gain a following. That's when Vox stepped in and offered us some gear as an endorsement, which wasn't common back then. Along with the Beatles and the Rolling Stones, The Standells were one of the early leaders using Vox amps – especially here in the States.”

Speaking of gaining a following, I'm sure appearing on an episode of The Munsters helped. How did that go down?

“Oh, absolutely. The Beatles were the biggest influence in my life of music – even bigger than Buddy Holly or Richie Valens. We were managed by Seymour Heller, who was Liberace's manager, and he got us signed to Liberty Records. Afterward, through the grapevine, Seymour discovered they were looking for a band to be on The Munsters because The Beatles had turned them down. So, he got in touch with the producers of The Munsters – they came down and saw us play at a small club and hired us for the show.”

And how did The Standells end up covering The Beatles' I Want to Hold Your Hand?

“Well, they wanted The Beatles, so the deal was that if The Standells were going to be on The Munsters, we had to dress like them and do I Want to Hold Your Hand. It was a lot of fun, and to this day, people are surprised when they find out we did that. I'm proud to say that we actually learned the song for real and didn't fake it. I still remember Herman Munster [Fred Gwynne] taking my Telecaster and wearing it around his neck [laughs].”

Seeing you played the song live rather than lip sync, was learning George Harrison's parts challenging?

“Oh, my God, yes, it was. I played very differently from George Harrison, and his parts were more complicated than you'd think. The Beatles were geniuses, and I remember thinking, 'Oh, God, now I gotta learn to play like my biggest influence.' But I tried hard and got close to that sound, but not all the way [laughs]. It was very challenging, and my Telecaster didn't quite match the sound – George used an Epiphone, but I did have the same Vox.”

Did you use that same Telecaster and Vox setup when you recorded The Standells' biggest hit, Dirty Water?

“Yes, I had my Vox AC30 and my Telecaster. I remember the way I got that sound was one night I was messing the settings on the Vox, and it had this switch that turned the amp from lower watts to higher, and I flicked it to the higher watts and was like, 'Wow, what an incredible sound.' It was incredible and magical, and that's the setting I used to record the riff for Dirty Water. And then later, I added onto the track with some extra guitars through my Fender Super Reverb.”

Did it come as a surprise that many of those same sounds and techniques were adopted during the '70s punk rock movement?

“It was unbelievable. I had no idea that all the stupid, crazy things I was doing on my guitar would influence punk rock. I remember when I found Ernie Ball strings and got turned onto those. And I loved them because they made the action of my Telecaster's neck not feel so high. Another part of that was adding paper shims to the neck pocket, which helped with the action, too.

“All those things and that sound were part of what punk rock guys in the '70s and '80s were doing. As for the riffs, I never imaged my sound would be part of punk… it came as a total shock.”

You're still as active as ever. What's on tap for you?

“I've been recently revisiting some Standells songs, which I put out on Dirty Water Revisited. Many of those songs were crude, and I wanted to give them a second life. I'm still writing and recording daily at home, working with a new deal from Big Stir Records.

“I've got a lot of original material that I want to get out, and I want to get out and tour. I've got shows booked, and I could not be more excited about keeping this music alive. That's all I know how to do. I’m 82, but for me, it's rock 'n' roll forever.”

Andrew Daly is an iced-coffee-addicted, oddball Telecaster-playing, alfredo pasta-loving journalist from Long Island, NY, who, in addition to being a contributing writer for Guitar World, scribes for Bass Player, Guitar Player, Guitarist, and MusicRadar. Andrew has interviewed favorites like Ace Frehley, Johnny Marr, Vito Bratta, Bruce Kulick, Joe Perry, Brad Whitford, Tom Morello, Rich Robinson, and Paul Stanley, while his all-time favorite (rhythm player), Keith Richards, continues to elude him.