The story of Paul McCartney and Wings

It’s been 50 years since Macca walked away from the biggest band ever formed. Here's how his post-Beatles career took flight

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

You think that when your favorite band releases an album every three years, that’s normal? Compare that to Paul McCartney, who – in his first decade of music-making after the split of the Beatles in 1970 – released two solo albums and seven more with the band Wings, as well as touring at all levels of the music industry, from universities to arenas.

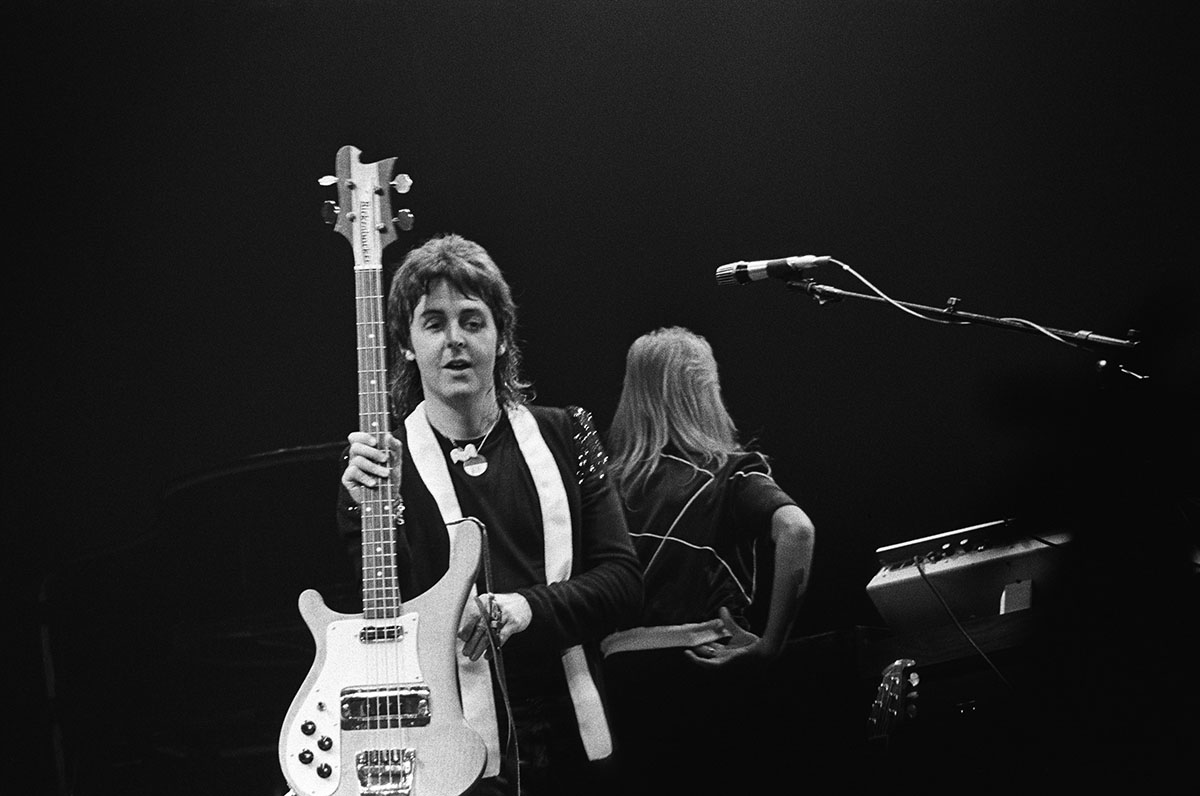

The man was incredibly busy, even though – as a millionaire since he was 25 – he could easily have spent the rest of his days sipping cocktails on the Mull of Kintyre. It wasn’t all easy going, though. Inevitably, it took the most famous bass player in history a little while to start firing on all cylinders again after the four-way divorce of the Fab Four.

Plagued by depression and embroiled in an existential crisis, he was pulled out of the rabbit-hole by his wife Linda, for whom he wrote Maybe I’m Amazed before the Beatles split. The song appeared on his first solo album, McCartney, recorded entirely by him apart from vocals from his ever-supportive wife.

The LP was released in April 1970, after Macca had walked away from the other three but before the band had legally dissolved. Now, here’s a thing. McCartney’s first solo record, along with every single album he’s released since then, has always been compared against his work in the Beatles, and it’s always come out on the wrong side of that equation. In a sense, this has been unavoidable.

The Beatles’ catalog contains so much gold – and so few misfires, relatively speaking – that no artist, whether you’re the Rolling Stones, Drake, or Adele, could hope to match it. That includes McCartney himself, who knew from day one that people were comparing Wings to his golden era of the '60s – but he got over it as the years passed.

I used to think that all my Wings stuff was second-rate, but I began to meet younger kids, not kids from my Beatle generation, who would say, ‘We really love this song’

Paul McCartney

“I used to think that all my Wings stuff was second-rate, but I began to meet younger kids, not kids from my Beatle generation, who would say, ‘We really love this song’,” he later said. That huge millstone around his neck aside, it should also be noted that McCartney changed his approach a little when he embarked on his solo career.

Adjectives such as ‘homegrown’, ‘organic’, ‘indie’, and ‘lo-fi’ suited his new music down to the ground; picture the man on a Scottish farm, surrounded by wife, kids, and livestock and strumming a ditty about how good life is out in the country, and you’ll get the picture. This approach wasn’t for everyone, least of all fans of the Beatles’ high-concept, avant-garde work. Compare the winsome Lovely Linda against the apocalyptic A Day In The Life, for example.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Then there was 1971’s Ram, on whose cover McCartney was pictured with the eponymous mammal: The artwork consolidated his image as a millionaire living comfortably off his Beatles royalties with nothing much of note to say. This isn’t to say that the songs were bad, or that the musicianship lacked craftsmanship and dedication – the song ‘Uncle Albert/Admiral Halsey’ was a deserved US Number One – but after the white heat of his old band, McCartney’s output now seemed a little, well, lukewarm.

It took the formation of a full-blown band, Wings, for the critics – never the most supportive audience when it comes to band-members who go solo – to take Macca seriously again.

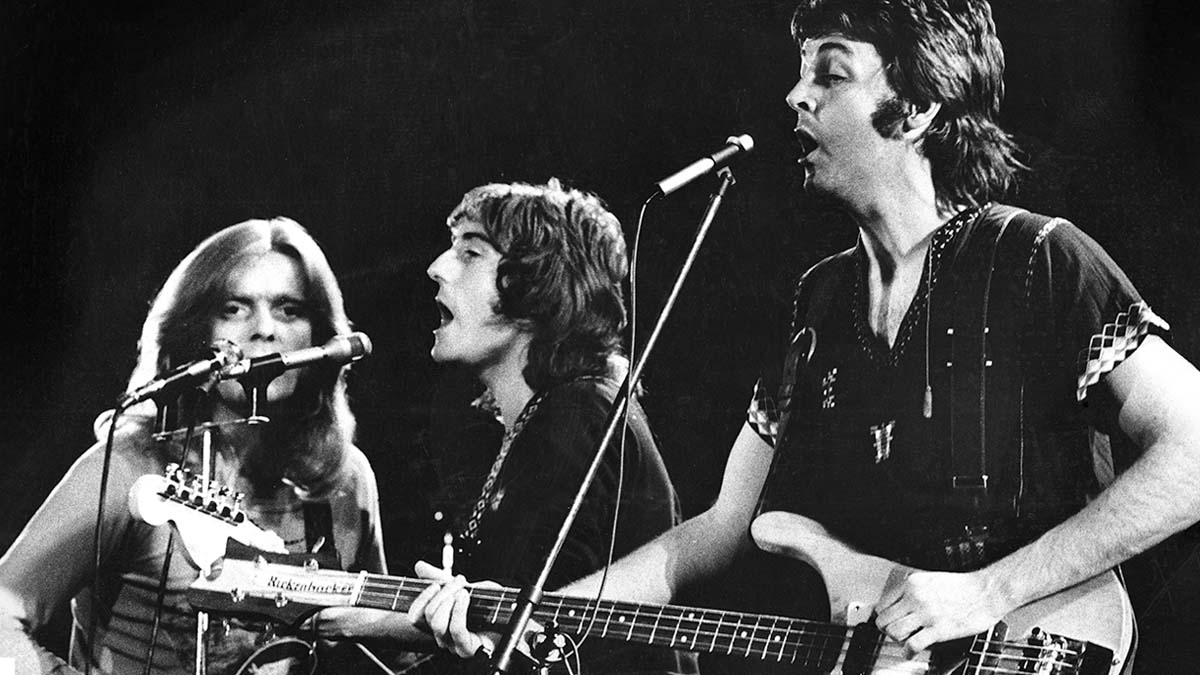

Ex-Moody Blues guitarist Denny Laine, drummer Denny Seiwell (what were the chances of two Dennys in the same band?) and McCartney himself made for a seriously talented group of musicians. That said, the addition of Linda as keyboard player provoked some criticism: She was not a trained keys player, and accusations of nepotism were rife.

Still, a low-key debut tour helped win McCartney’s critics over. Wisely, he first arranged for Wings to play 11 shows at university level, entertaining merely hundreds of music fans. The band, now joined by guitarist Henry McCullough, were on a budget, staying in affordable accommodation, a fact noted by sceptics with approval.

McCartney later explained, “The main thing I didn’t want was to come on stage, faced with the whole torment of five rows of press people with little pads, all looking at me and saying, ‘Oh well, he’s not as good as he was’. So we decided to go out on that university tour, which made me less nervous... by the end of that tour I felt ready for something else, so we went into Europe.”

Mull Of Kintyre is still the most successful non-charity single ever released, thanks to its heartstring-twanging lyrics about the pleasures of the countryside and its stirring bagpipe parts

Twenty-five continental shows later, Wings were now an understood quantity, if not entirely a welcomed one: That would require new music, and convincing music at that. 1971’s Wild Life LP was a fairly mild debut, but an American chart-topper in My Love really stamped Wings’ presence on the world and made their second album Red Rose Speedway [1973] a bona fide hit.

The band’s profile was given a further boost the same year by the enormous success of Live And Let Die, the theme song for the James Bond film of the same name. An operatic, highly dynamic composition that managed to combine the usual Bond trademarks with a spellbinding hookline, the song remains one of Macca’s finest ever, a fact noted by Guns N’Roses when they covered it in 1991.

The song was nominated for an Oscar and bagged producer George Martin a Grammy for his orchestral arrangement. The remainder of the '70s was a hugely successful period for Wings, who released a series of platinum-selling albums.

The first was the Grammy-winning Band On The Run, which was inescapable through 1974, remaining on the UK chart for 124 weeks. Venus And Mars [1975] and Wings At The Speed Of Sound [1976] were just as successful despite the group’s fluctuating line-up, making Wings a viable concept even to the most hardened cynic. The inclusion of a few Beatles songs in Wings’ setlist was a turning-point. McCartney was at peace with his past as well as appreciative that fans wanted to hear the songs again.

After an American chart-topping triple live album, Wings Over America [1976], it’s arguable that Wings peaked. Punk rock was on its way, after all – but that didn’t stop McCartney putting out the biggest-selling single of his career, as a Beatle or not.

Mull Of Kintyre, co-written with Laine, was a commercial behemoth, outselling every other song in history until Band Aid’s Do They Know It’s Christmas? seven years later. Mull Of Kintyre is still the most successful non-charity single ever released, thanks to its heartstring-twanging lyrics about the pleasures of the countryside and its stirring bagpipe parts.

Although London Town [1978] supplied another US Number One in With a Little Luck, and Back To The Egg [’79] featured a supergroup including Pete Townshend (the Who), David Gilmour (Pink Floyd), Gary Brooker (Procol Harum), and John Paul Jones and John Bonham of Led Zeppelin, the writing was on the wall for Wings. After a second solo LP, McCartney II, was a major hit in 1980, Macca disbanded Wings the following year.

Was this a wise move? That’s debatable. The '80s was a mixed decade for McCartney, as it was for so many musicians of a certain vintage.

Now sporting a mullet and worryingly fond of loud check jackets, he embarked on a series of projects that were more or less cringeworthy. The best of these was Ebony And Ivory, a 1982 collaboration with Stevie Wonder, but even so, its lyrical metaphor was a touch hamfisted. Two more collaborations, this time with Michael Jackson, were commercially successful, even if their quality was questionable.

The Girl Is Mine and Say Say Say had their charms, for sure, but they were supremely bland: Was this really the same Paul McCartney who had recorded Helter Skelter and Back In The U.S.S.R.? It got worse, with the sugary Pipes Of Peace a hit in 1983 among grandparents worldwide. The following year, McCartney wrote, produced and starred in a musical film called Give My Regards To Broad Street, described by Variety as “characterless, bloodless, and pointless”.

The song No More Lonely Nights was a pleasantly inoffensive ballad, for sure, but then McCartney made the curious decision to release a juvenile Rupert Bear-themed song called We All Stand Together in 1984, perhaps his worst ever creative move. Fortunately, things began to look up for our man after this point, with the moderately entertaining film and song Spies Like Us, both released in 1985.

In July, the biggest live gig there has ever been or will ever be, Live Aid, took place – and while much has been written about its role in turning rock music into corporate fodder for inefficient charities, it cannot be denied that asking McCartney to close the show with Let It Be was a masterstroke of the highest order.

The fact that his microphone wasn’t working for the first few seconds of the song somehow added to the surreal charm of this massive event. That was it – the turning-point that was needed. McCartney, and his fans, were reminded of what an icon he had been, and he set about making good on that legacy with a series of decent records.

Press To Play [1986] made it clear to listeners that he was still a rocker at heart, and the 1988 LP CHOBA B CCCP – literally Back In The U.S.S.R. – confounded expectations by being released only in the Soviet Union: a provocative move in the pre-glasnost era.

Highlights of Macca’s American presence in recent years have included a tribute to The Ed Sullivan Show in an episode of The Late Show With David Letterman in 2009; three gigs at Citi Field, which replaced the Shea Stadium in Queens, New York, the same year; a double live album called Good Evening New York City commemorating those shows; the opening show at the Consol Energy Center in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania in 2010; and two sold-out concerts at the new Yankee Stadium in 2011.

Do you see Bruce Springsteen, Bob Dylan, or any other American artist of McCartney’s generation being asked to open British venues on a regular basis? No, you don’t, which says something about the ongoing, and welcome, love affair between the USA and the Beatles.

Musically, McCartney remains active on multiple levels. He released an album of covers called Kisses On The Bottom in 2012, jammed with three former members of Nirvana at the Concert For Sandy Relief the same year, and released another studio album, New, in 2013.

Another celebration of The Ed Sullivan Show occurred the following year, this time in some depth; McCartney, Ringo Starr and others played a 22-song Beatles set in an event called The Night That Changed America: A Grammy Salute To The Beatles, with typical showbiz understatement.

This brings us up to date, with the McCartney brand still very much a cutting-edge concern; his album, Egypt Station, went to Number One in America in 2018, while the unexpected pandemic album McCartney III was met with serious critical praise last year.

He’s working on a stage musical, an adaptation of the 1946 film It’s A Wonderful Life. What’s more, a major documentary called The Beatles: Get Back is on the way from Lord Of The Rings director Peter Jackson, so McCartney won’t be resting on his laurels for long. We’ve said it before, but it bears repeating: Which musician of Paul McCartney’s generation is as creative, as active, or as relevant as he is in 2021? There is none; he stands alone. We salute him.

Joel McIver was the Editor of Bass Player magazine from 2018 to 2022, having spent six years before that editing Bass Guitar magazine. A journalist with 25 years' experience in the music field, he's also the author of 35 books, a couple of bestsellers among them. He regularly appears on podcasts, radio and TV.