Rik Emmett: “If I wrote a pop tune, the guys wanted to make it heavy. I’d put more power chords in and Townshend it up. For a while, it worked”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

During the late ’70s and into the ’80s, few bands were pilloried by music critics quite like Triumph. “Faceless” and “corporate rock” were two of the tags regularly assigned to the Canadian power trio composed of guitarist-singer Rik Emmett, bassist Mike Levine and drummer-singer Gil Moore, and those were some of the kinder descriptors lobbed at the band.

Admittedly, Triumph never professed to be anything more than a sleek, well-oiled, turbo-charged outfit that blitzed its audience with smoke bombs, lasers and flame throwers while dishing out headbanging, fist-in-the-air AOR anthems like Lay It on the Line, Magic Power and Fight the Good Fight. Hell, they even called one of their albums Rock & Roll Machine, just in case their subtlety went over anybody’s heads, and to celebrate their razzle-dazzle stage act, they titled a song Blinding Light Show.

“We certainly weren’t a critics’ band,” Emmett says unapologetically. “When Mike and Gil started the band, they envisioned a big production with lots of lights and effects. They called it Triumph for a reason – this was a band for the punters in the back seats who were having a hard time in life. We gave them inspirational messages, and we put on a big show. Critics were never going to like us. They didn’t like bands like Styx or Foreigner or Rush. Rolling Stone hated those bands.”

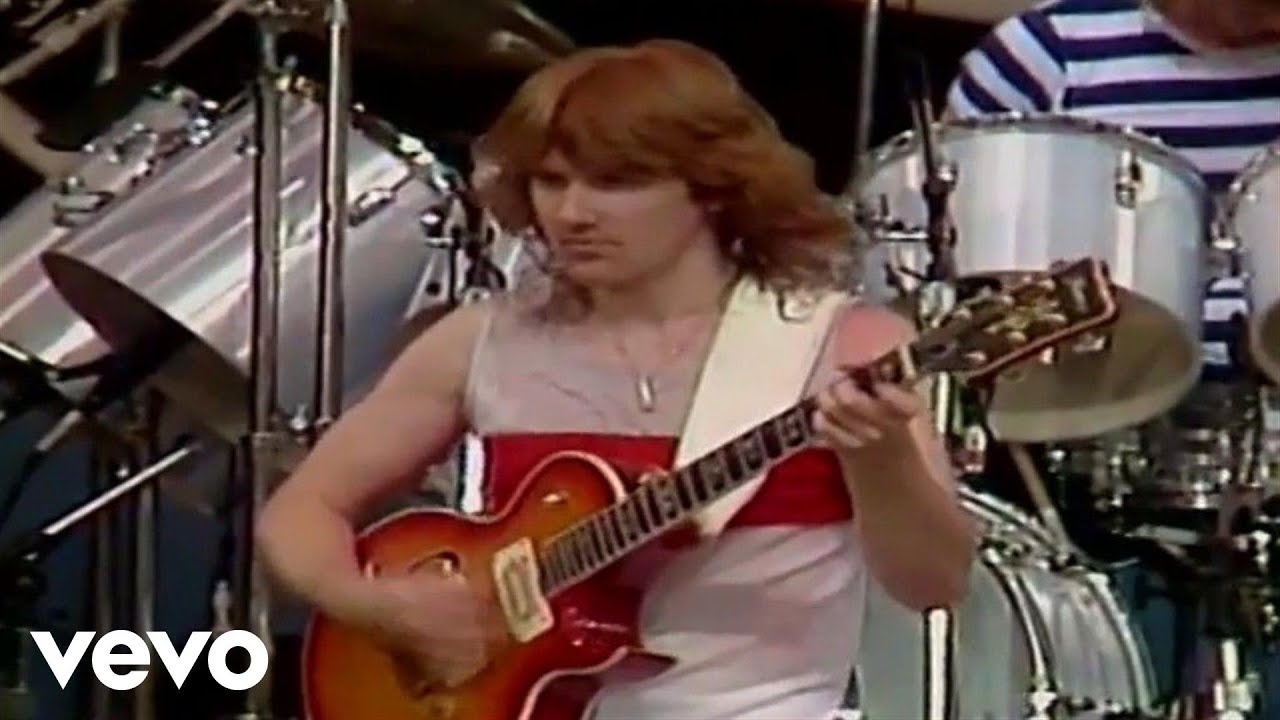

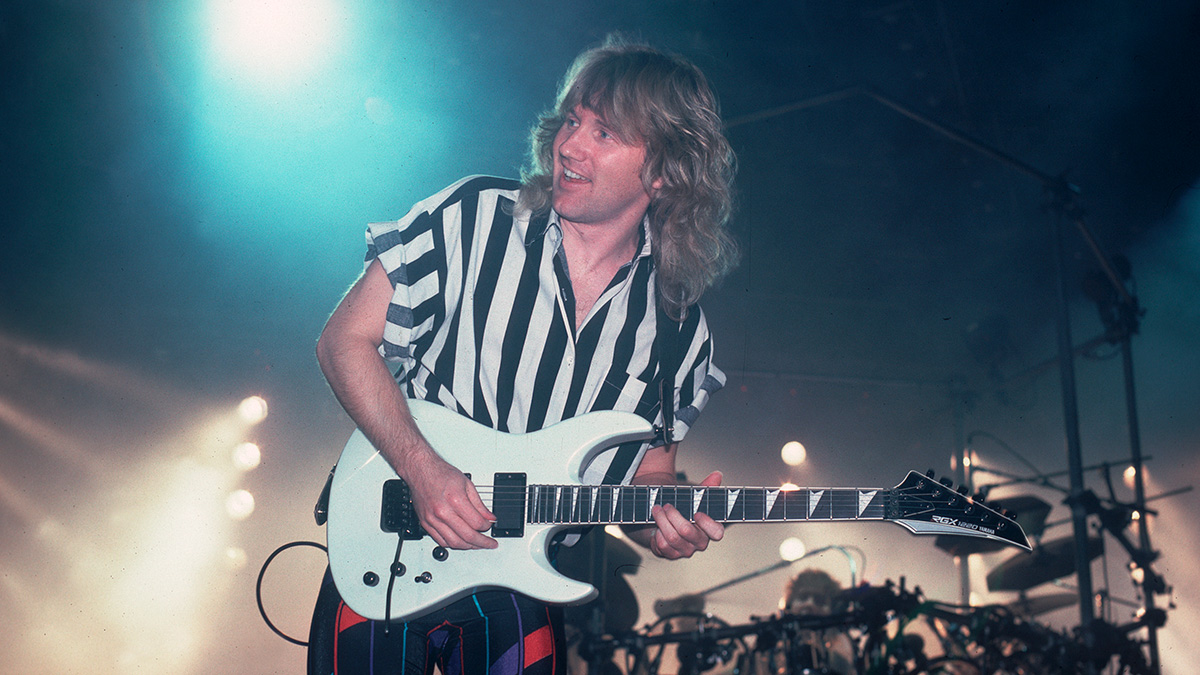

Emmett himself provided critics with plenty of ammunition. At a time when punk and new wave fashion varied between short hair and leather (the Clash, the Sex Pistols) or short hair, suits and skinny ties (Blondie, the Knack), the feather-haired guitarist’s choice of stage attire – red, white or black skin-tight, chest-baring jumpsuits, not unlike the getups favored by Ted Nugent – was the antithesis of cool.

“Obviously, there was a bit of a cartoon element going on,” he says, “but when you start out in a rock band, you want to look larger than life. I was cocky, and I was in a rocket ship that was taking off. When you’re 25 years old, you’re not thinking of growing old gracefully. It wasn’t until I was in my mid-30s that I started to mature.”

He laughs, then adds, “But you know, there was a very functional element to those jumpsuits. After the show, I could go back to my hotel and hand wash them in my bathroom sink. That would get all the sweat and smell out. I’d let them drip dry over the shower, and by the next day I was good to go.”

Finding success in their homeland wasn’t an automatic for Triumph (“It took us a few years to live up to our name,” Emmett jokes); it wasn’t until 1977, when they released a cover of Joe Walsh’s Rocky Mountain Way, that they received real radio play.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Cracking the U.S. market was even tougher. Finally, in 1979, their feel-good rocker Hold On won over FM deejays in the Midwest, and their next single, Lay It on the Line kept the ball rolling, propelling the band’s third album, Just a Game, to gold status. But even as Triumph made inroads in the States, they faced constant comparisons to another hard rock Canadian trio.

“I mean, you’ve got two three-piece bands from Canada, the lead singers sing kind of high, and the guitar players are blond – I get it,” Emmett says. “Musically, Rush were quite different from us. They became much more progressive-minded, and their whole ensemble became a very conscientious kind of activity. The band I was in was something else entirely.

“Gil would have been quite happy to play in Kiss or Bad Company. I aspired to a higher level. I wanted to write songs that approached pop, but the other guys wanted that blues base. They wanted arena heaviness. Eventually, there was tension between us, and after a while I wanted out.”

I wanted to write songs that approached pop, but the other guys wanted that blues base. They wanted arena heaviness. Eventually, there was tension between us

Emmett quit Triumph – acrimoniously, in 1988 – at a time when the band’s brand of brawny rock was being eclipsed by video-ready groups like Mötley Crüe, Bon Jovi and Guns N’ Roses.

Levine and Moore soldiered on with Canadian session star Phil X attempting to fill Emmett’s shoes, but by 1993 they packed it in. Emmett, on the other hand, enjoyed considerable success as a solo artist, issuing numerous albums that touched on rock, pop, jazz, classical and folk.

Emmett didn’t speak to his former bandmates for almost 20 years. “There was a lot of damage done, and I was very hurt,” he says.

Finally, in 2007, they appeared together in Toronto when they were inducted to the Canadian Music Industry Hall of Fame, and they reunited for three concerts over the years – their last performance was at a Triumph Superfan Fantasy event in 2019 that was filmed for the 2021 documentary, Triumph: Rock & Roll Machine.

“The documentary was kind of a sanitized Triumph version of everything,” he says. “I’ll be coming out with a memoir soon, and in that you’ll get my truth.”

When you joined the band, it was pretty much run by Gil Moore. Did that give you pause for thought at all?

“No, it didn’t. We had kind of a Three Musketeers mentality. Yes, it was Gil’s band. His name was on the contracts, and he ran the production. He signed every check. There was never any problem with that. Then Gil and Mike decided they wanted to sue RCA and get out of the contract, and we went to MCA and had a mountain of debt. Then the MCA records didn’t go so well. Tensions started to build, and it went down the toilet in ’86.”

You liked a lot of British guitarists, but you were also a jazz fan. How did that fit with what Gil and Mike wanted to do?

In college, I got into Wes Montgomery and Kenny Burrell. I saw jazz as a logical part of my evolution as a guitar player

“Well, blues was a common ground for everybody. Rock ’n’ roll has blues, as does jazz. But if I wrote more of a pop tune, the guys wanted to make it heavy. I’d put more power chords in and Townshend it up. For a while, it worked.

“But yeah, I loved all those English guys – Beck, Page, Clapton. Of course, I came up with the Beatles, and I loved Hendrix. Ritchie Blackmore was very influential for me. His phrasing and his choice of notes was very unique. Steve Howe was another one. In college, I got into Wes Montgomery and Kenny Burrell. I saw jazz as a logical part of my evolution as a guitar player.”

The band got its first real airplay with the Rocky Mountain Way cover. Is that the kind of thing you guys would jam on?

“Yeah. When we started out, we had three sets: one was Led Zeppelin, another was a Zeppelin medley, and then we’d do a few tunes that Gil would sing. Rocky Mountain Way was one of them. We were in the studio and we didn’t have enough material, so we recorded Rocky Mountain Way. Canadian radio was all over that.”

As the documentary makes clear, Gil was behind the band’s flamboyant stage show. What did you think of the big production?

“When the band came together, Gil had more of a youthful ambition, and Mike was more of a riverboat gambler dude with the same ambition. I had the same ambition. I thought they were the smartest musicians I ever met. They looked at me and said, 'Look at this guy. He can sing and play. He can run around the stage and put on a show. He’s up for it – he’ll wear the jumpsuit!' [Laughs] And I was into it. We had common ground with all that.”

When we signed with RCA, we devised a plan: We went to the bank and took out a huge loan, and we bought a tractor trailer truck, a big PA and lights

It was pretty hard for the band to make it in the States. Did you ever think it wouldn’t happen?

“There were times when I thought that, but Gil and Mike? No way. Their goal was to break the States, not Canada. It was hard, man – impossible! When we signed with RCA, we devised a plan: We went to the bank and took out a huge loan, and we bought a tractor trailer truck, a big PA and lights. When we went to a place like Pittsburgh, we could tell the promoter that he didn’t have to pay for all the production – we had our own stuff. That way, he could pay us more.

“Mike and Gil were very smart about touring. Mike would go to radio stations and get them to promote our shows. We’d do really cheap tickets – 99 cents at the door. The stations would saturate the market with ads, and we’d blow people away with flame throwers and lights. Each time we created a sensation. That’s how it started. Mike and Gil had a vision.

“Of course, I was pretty damn good. You’d go to the gig and see Rik Emmett sing and play. If I had sucked, none of it would have worked. But I didn’t suck – I was pretty damn good. That sounds egotistical, and I don’t mean it to. I wasn’t the best guitar player or singer, but when you saw me, you’d say, ‘Shit, man, that guy is pretty good.’”

You played a number of electric guitars with the group – doublenecks by Gibson, Ibanez and Dean. But your main guitar was the Framus Akkerman. What was so special about that model?

“It was very playable. What I liked about it was, it gave me an identity. Nobody was really using it back then. Even Jan Akkerman wasn’t playing it that much. It had a very wide nut – the fingerboard was almost classical. Once I got accustomed to it, I found it made everything very easy to play. I probably had a bit of a fingerstyle element to my playing, so I didn’t like skinny necks. The whole semi-acoustic vibe was cool. It was somewhere between a Les Paul and a 335.”

For the first half of the ’80s, the band was a big arena draw, but your album sales and radio play didn’t match the concert tickets you sold. Was that a hard dichotomy to reconcile?

“You know, we always presented ourselves as an arena band, even in the beginning. We pushed the live show. I remember when Allied Forces came out, we were on FM radio and we went gold. The other guys said, ‘RCA sees us as this cultist band that’s only good for gold. We want a bigger record deal. We want out. We want a label that will give us the promotion budgets like they give to Styx and Foreigner.’

“The thing is, in hindsight, the world was changing and we were falling out of favor. A slickness was starting to happen with bands like Bon Jovi.”

Around this time, the band was being pressured to come up with hit singles and to spruce up its image in videos.

“Yeah, and that didn’t feel like me. I love songs and songwriting. Videos… Duran Duran were doing things with tigers and fashion models. Suddenly our hair wasn’t big enough. We had to have makeup. I didn’t know what it had to do with our music. At that point, I wanted to make my music elsewhere.”

How long were you thinking “This is the end” before you decided to call it a day?

“You see, you’re stealing stuff from my memoir. [Laughs] After a while, I said, ‘Whoa, I don’t want to do this anymore. How do I find the exit door?’ The unhappiness began when we did the label change from RCA to MCA, around ’83 and into ’84.

“I was becoming very skeptical and unhappy about what the band was and what it meant for me. We had so much business together, though, so it was hard. I went to the band’s lawyer and said, ‘How do I get out of this?’ He would say, ‘Oh, don’t go there. You keep quiet and we’ll figure out how to cope.’ By ’86, ’87, I said to the guys, ‘I want out,’ and by ’88, that was it.”

You didn’t talk to Gil and Mike for almost 20 years. What was the ice-breaker?

“Around 2006 my brother got sick with cancer. He was talking about tying up the loose ends in his life, and he said, ‘You’ve got baggage you need to fix.’ I was like, ‘Oh, fuck off with that – don’t put it on me.’ I didn’t want to hear it at first, but that was a catalyst. It took a long time. Finally, around 2007, I said, ‘OK.’ Yeah, it was almost 20 years.

“There’s a part of the documentary that goes, ‘And at the height of their popularity, the guitar player leaves!’ And I thought, ‘Oh, God, that’s not true.’ I’ve got a lawyer reading the chapter in my book where I go into it, just to make sure it’s kosher. I hope I don’t blow up the good that I’ve done with the reconciliation.

“It’s nice to see those guys again. I have my own life and business, and I don’t have to be part of theirs. That was one of the conditions when I came back. I said, ‘If you want to play some gigs, fine. But I’m not in the band anymore.’”

It’s weird to have these reinterpretations of our songs. I can only imagine what it was like for Leonard Cohen to hear two dozen versions of Hallelujah in one year

There’s a Triumph tribute record in the works. Are you involved at all?

“No, Triumph isn’t part of my business. I’m at arm’s length from all of it. Mike Clink is producing the record. I don’t know who all is doing versions, but I do know that Andy Curran did a version of Blinding Light Show with Alex Lifeson. He played it for me, and it was wildly different from what we did. It was terrific, but completely reimagined.

“It’s weird to have these reinterpretations of our songs. I can only imagine what it was like for Leonard Cohen to hear two dozen versions of Hallelujah in one year. I take a cue from him. Whenever somebody asked him, ‘What do you think of that version of Hallelujah?’ he said, ‘Oh, that’s one of the best things I ever heard.’ [Laughs]”

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.