“There were no fret markers on it, so all I could do was try to keep a straight face and guess!” Fretted, fretless, double bass, eight-string – Sting is unstoppable on bass. Here’s how he developed his style

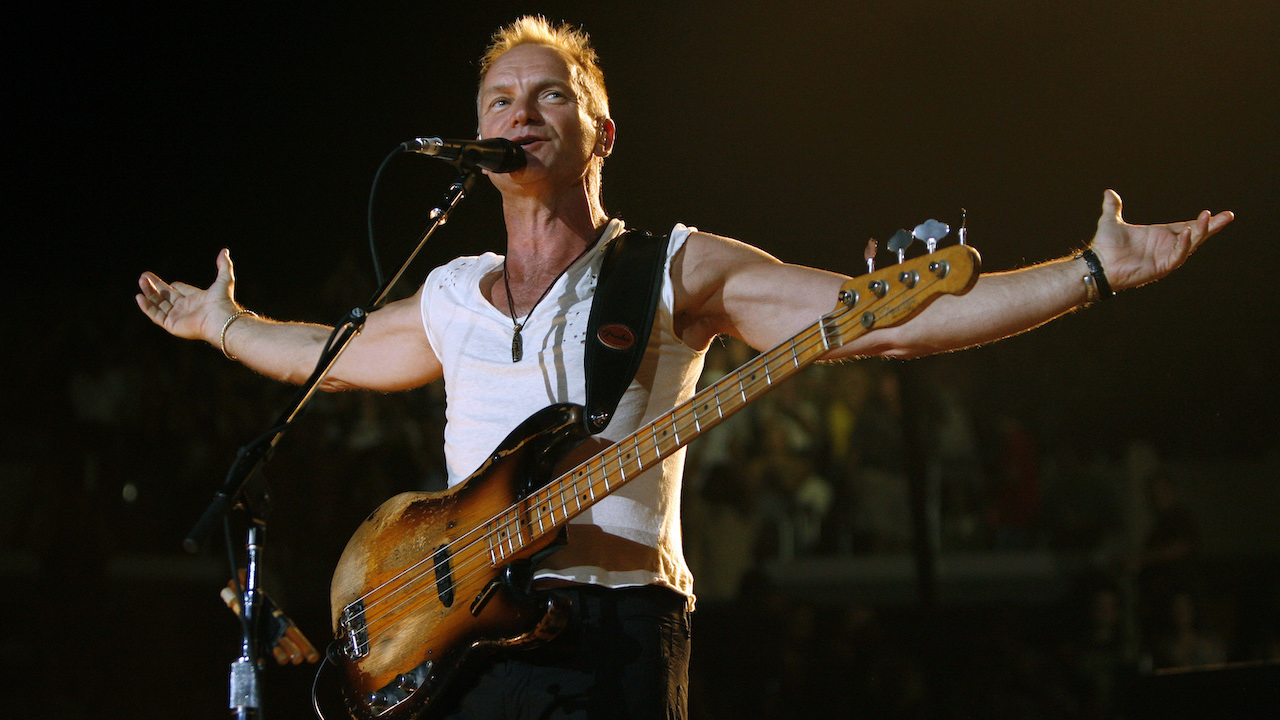

Songwriter, actor, author, activist, rock star, jazz freak... Gordon 'Sting’ Sumner is quite the renaissance man. Oh, and he played bass in The Police…

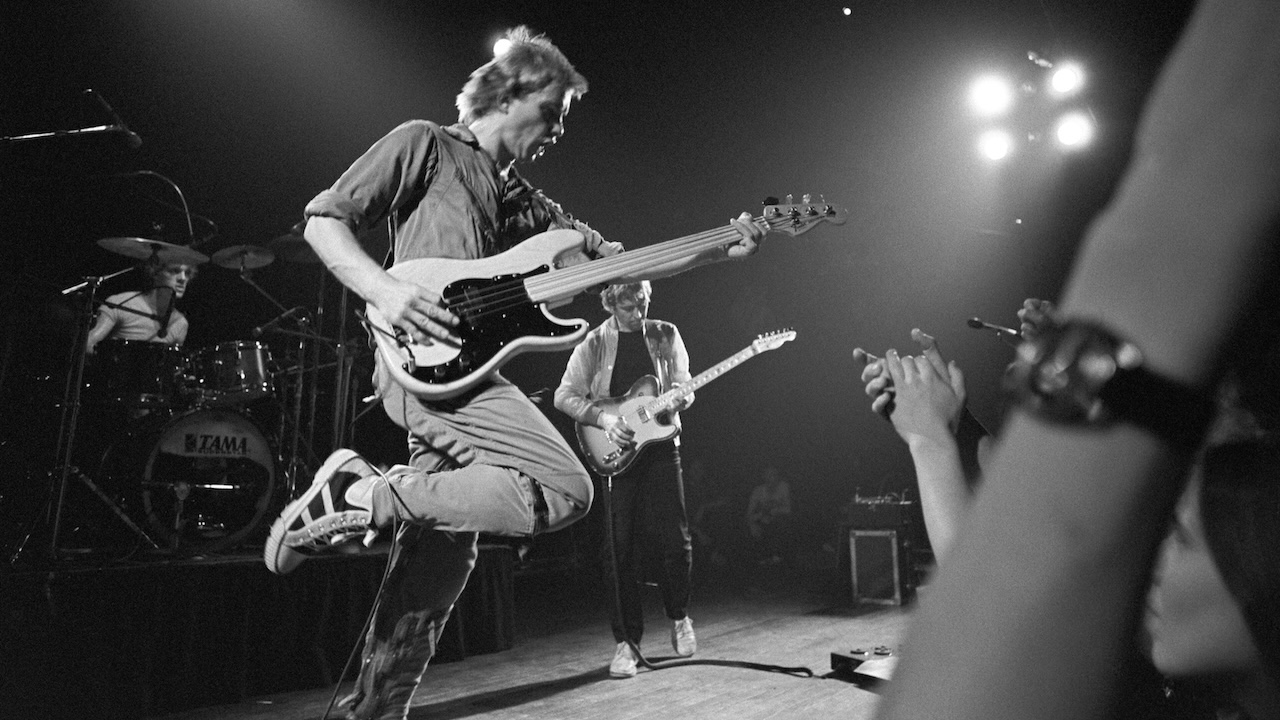

Sting vividly recalls the first time he played a fretless bass. He'd just arrived in America with guitarist Andy Summers and drummer Stewart Copeland to promote the first Police single, Roxanne. They headed directly from the airport to the legendary music shops of 48th Street where Sting bought the first fretless bass he saw, a Fender Precision.

Then, in typical risk-taking fashion, he proceeded to play it that night at CBGB’s – without practicing beforehand. “There were no fret marks on it,” Sting told Bass Player. "So all I could do was try to keep a straight face and guess!”

You may know Sting as the guy who fronted the Police, or the solo artist who sold a gazillion copies of songs like Fields Of Gold, Russians, or Englishman In New York. Your kids know him as the funny levitating guy from Bee Movie. Everyone knows Sting for something.

In bass world, though, we know the guy as Gordon Sumner, the ex-teacher born in 1951 who played in jazz and fusion bands before forming the Police in 1977, playing whopping great basslines and being a massive rock star.

Fretted, fretless, double bass, eight-string – Sting was unstoppable on bass, filling up the empty spaces within the trio format of the Police with a variety of lines, from the simple to the finger-threateningly complex.

The following interview from the Bass Player archives took place in April 1992, with Sting having just released his third post-Police album, The Soul Cages.

The Soul Cages deals with issues left over from your childhood in Newcastle. Was your family musically inclined?

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“Not professionally, although my father had a beautiful voice and played the banjo – not very well, but he could hold a tune. My mother was a very good piano player. Some of my earliest memories are of listening to her play.”

Did you ever sing or play as a family?

“If we were a bit drunk! I actually started on guitar – we had a band down at the local youth club, and I remember learning all of Eric Clapton's solos on John Mayall's Bluesbreakers. I was a much better guitarist at 16 then I am now.”

What prompted the switch to bass?

“I suddenly realized one day that I had to play the bass to make it. Newcastle was an economically depressed, northern English town – the only ways out were things like sports, education, and music. We were working class, and breaking out was not easy. Even if you did, you were still tagged as working class.”

Any role models early on?

“Jack Bruce, definitely. And Paul McCartney was a model in terms of being a bass player and a songwriter. He had a good understanding of the bass's function, both melodically and contrapuntally. Anyone who plays bass and sings knows that most bass parts go against the rhythm. It's a counterpoint, and if you're singing on top of it you've got two lines weaving in and out of each other.”

When you write, do the bass parts come after the melody or along with it?

“I never think much about the bass parts while I'm writing, to be honest. I just make them up on the spot once I've written the song, with an eye towards being able to sing at the same time.”

Your basslines have a Zen-like blend of sophistication and simplicity. Didn't jazz arranger Gil Evans compliment you on that?

"When I met Gil, I was surprised and flattered that he knew who I was. He mentioned that he loved the bassline to Walking on the Moon, and that has to be one of the greatest compliments I've ever received.

“At the time, I was looking for someone to be my mentor in terms of arranging. I was working with an eight-piece group, and the Miles Davis albums that Gil helped to arrange were a vital part of my musical education and inspiration. We recorded Little Wing with Gil's band, but he wasn't really involved as an arranger – he was more of a spiritual guide and counsellor.

“At one point, I was having a problem with one of the songs and kept going over this one note, changing it, trying to make it fit. Gil quietly pulled me aside and said, ‘It's not that note; it's the one just before it. Change that note and everything else will fall into place.’ He was absolutely right. It was magic.”

Do you prefer to record your bass direct?

“Yes, I usually plug right into the board. In the Police we'd all play in the same room, and all I'd hear was Andy's guitar – which needed to be loud to get that natural distortion – and Stewart's drums. But I hate the sound of a bass guitar coming through headphones – it sounds like a mechanical fart. So nowadays I play in the control room, where I can get a warmer sound and can mix and adjust the other instruments to approximate how they'll sound on the record.”

You sometimes double-track your basslines, don't you?

“I often use the double bass over the original electric basslines, because the double bass has overtones that you feel – a big subliminal undercurrent of sound. We used that combination on All This Time on The Soul Cages. Sometimes I use an old Italian bass, but I often use the Z.”

Where did you get the Z Bass?

“It's a Van Zalinge electric standup I got in Holland a decade ago, when the Police were recording Zenyatta Mondatta. You can hear it on the original Don't Stand So Close to Me. I also used the Z Bass on Every Little Thing She Does Is Magic. On Synchronicity, I combined it with a Precision fretless on Wrapped Around Your Finger and with a Steinberger on King of Pain.”

Do you think the lessons you learned from the breakup of the Police helped you to become a better leader of your own bands?

“One of the problems in the Police was that everyone wanted to be the guy who wrote the songs, and that couldn't be. In the Blue Turtles band, there was a sense that everyone knew what their function was. I got the best drummer, saxophonist, bassist, and keyboard player I could find, so I could concentrate on being the best singer and songwriter I could be. I didn't have to fight for my right to be the songwriter, so it was much more creative.

“Andy and Stewart certainly made key creative contributions to many of the Police songs, even if they didn't write them. They're fantastic musicians, and they did enhance the songs, but the songs themselves are very personal – that aspect had nothing to do with the band. Maybe this sounds terrible, but when people talk to me about Police songs, I say they aren't Police songs, they're my songs.

“Andy and Stewart had never been songwriters, but I'd been writing for a long time. Suddenly they were in a successful group, and they wanted to become songwriters overnight without having gone through any of the training.”

The Soul Cages deals with the death of your father. How much of that was planned consciously before you began to write?

“For almost three years, I hadn't written even one rhyming couplet. I'd written a lot of little fragments of music, but there were no real ideas coming out. I was genuinely frightened. At one point I thought, ‘This is it, I've just dried up!’ Then I started to wonder why. I think there was an awful lot of denial going on in my subconscious – there were things I wasn't ready to face.

“I spoke to Bruce Springsteen about it; he was just starting his own album, and I said, ‘Bruce, I don't know what to do. Have you got any bad songs you don't want?’ He offered me a couple. Then one day I just sat at the piano and started to free-associate, mumbling to myself – there was nobody in the house – and the mumbling got louder and gradually I started to sing lines.

“Island of Souls was one of the first. So I wrote down what I thought were just disconnected images and lines. Quite a few were about the sea, and all were linked somehow to my father and his death. Suddenly, I realized I was mourning my father, and then the whole thing poured out of me like a river – which became the central image on All This Time.”

There's a folkish feel to the album, but there's also a blend of jazz, rock, and African sounds.

“Absolutely. There is a very strong folk tradition where I come from in England, but I'm also a child of the radio. My music reflects that. As a kid I listened to the BBC, which was incredibly eclectic – everything from African music to classical symphonies. Jazz, too – Kenny Kirkland pointed out that a riff in Jeremiah Blues is similar to an old Herbie Hancock riff.”

There's less overt improvising on this album, but it sounds as if you're still developing your jazz sensibilities in the harmonies.

“The older I get, the more I like dissonance – that bitter harmony. There's a b5 harmony that I play at the end of The Wild Wild Sea, and a couple of the crew came up to me and said, ‘Hey, this is a mistake.’ I said, ‘No, it's a b5. It has a bitter quality about it, that's all.’

“This is popular music and it's pretty simple, but occasionally you can do little things that suggest something unusual. If I hear intervals that most people find horrendous, I love them. It demands a level of concentration that is very rewarding, but it's an acquired taste – like Campari, which I love.”

Nick Wells was the Editor of Bass Guitar magazine from 2009 to 2011, before making strides into the world of Artist Relations with Sheldon Dingwall and Dingwall Guitars. He's also the producer of bass-centric documentaries, Walking the Changes and Beneath the Bassline, as well as Production Manager and Artist Liaison for ScottsBassLessons. In his free time, you'll find him jumping around his bedroom to Kool & The Gang while hammering the life out of his P-Bass.