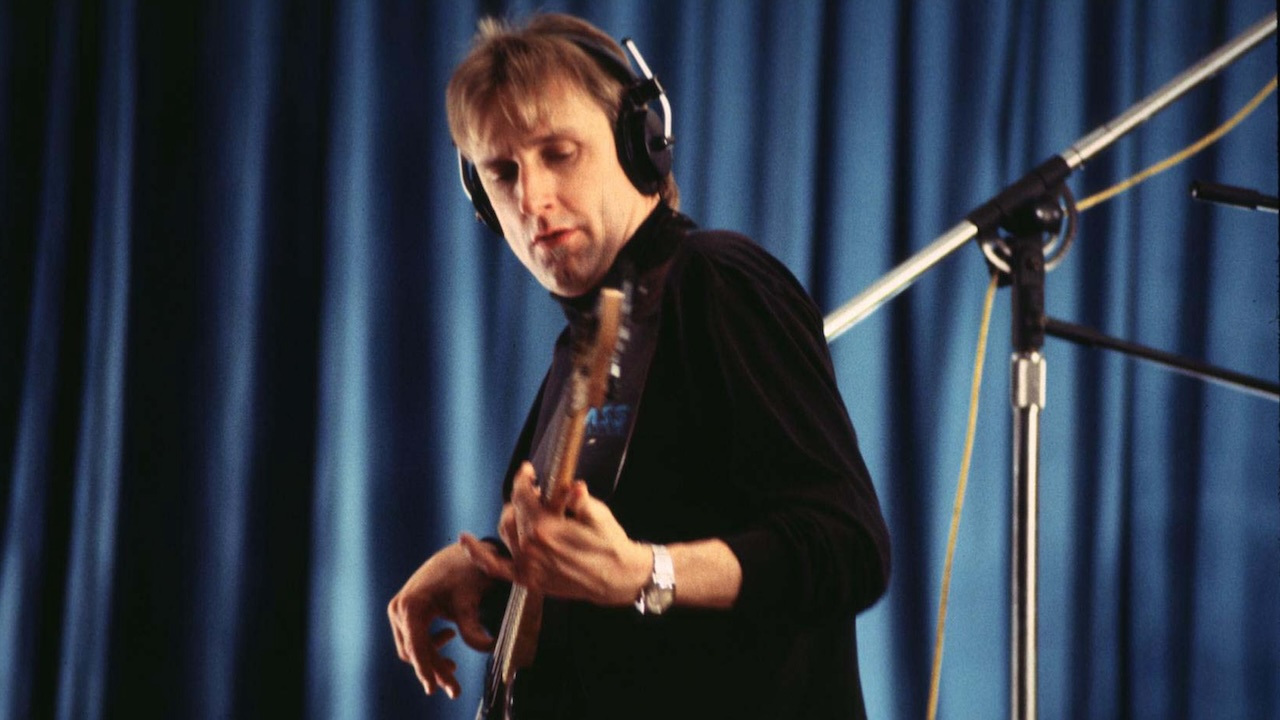

“We’d all been struggling with the track – I remember Ralph MacDonald’s hands were bleeding!” Longtime David Letterman bassist Will Lee recalls his toughest recording date in NYC

The session took place in January 1975 at Secret Sound Studios on West 24th Street

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

By his own admission, bassist Will Lee was spoiled by his early New York City experiences. Plucked from Miami to join the potent-but-doomed fusion band Dreams in 1971, Lee was soon doing jingles, album dates with Roberta Flack and Barry Manilow, and tours with Horace Silver and Bette Midler.

Meanwhile, at keyboardist Don Grolnick's small apartment on Carmine Street in the Village, he began rehearsing music that would become a cornerstone of the budding fusion movement and change contemporary jazz forever.

At the behest of record mogul Clive Davis, Lee's former Dream-teamers, the Brecker Brothers (trumpeter Randy and saxophonist Michael), signed with Arista and put together a band for their self-titled debut.

Drawing from their own diverse careers, which ranged from morning-cut pop albums to late-night straightahead jazz jams, the Breckers (with Randy as the main composer) created a startlingly fresh sound.

Sessions for The Brecker Brothers took place in January 1975 at Secret Sound Studios on West 24th Street. Lee played his sunburst '65 Fender P-Bass with Rotosounds and went direct to the board.

Notable among the nine tracks were jazz-rock burners Sponge and Rocks, and the disco-dallying Sneakin' Up Behind You, which crept up the pop and dance charts, thanks to Lee's vocal hook. But it was the aptly titled Some Skunk Funk that became an instant classic.

“The Breckers, Grolnick, David Sanborn, guitarist Bob Mann, and drummer Harvey Mason were all there to cut the track live," Lee told Bass Player. “We'd all been struggling with the material – it not only bends your ears, it bends your eyeballs trying to read it!

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“Well, Harvey came in the last day of rehearsal, taped the multi-page chart to his cymbal stand, counted it off, and started sight-reading it, 7/8 bar and all. It was like watching a feeding frenzy – he was just inhaling the notes!”

According to Lee, there were five or six takes, with maybe a few false starts, and no punches. “The horns may have redone their parts later, and Ralph MacDonald overdubbed some conga and shaker parts that, to me, are the track's secret ingredient – I remember his hands were bleeding afterward.”

The song starts with a dizzying pentatonic unison riff within a five-bar intro that ends on the bar of 7/8. Lee begins the A section of the song with a written two-bar groove pattern, with Mason's kick in close proximity.

The B section is another written figure, this one more of an answer to the horn melody, in a section that emphasizes the Breckers' signature triad-over-non-diatonic “slash chord” sound. These two sections repeat, the latter introducing a more involved bass counter-melody and slightly different angular harmonies.

The song's third section ups the funk quotient further. The first half of bars 38-43 are written (intertwined with the horn melody), while Lee improvised the walk-ups in the second half of those bars.

Following a restatement of the intro, Randy Brecker's electronically effected trumpet solo begins. Here, Lee opens up rhythmically by patting the strings with his fingertips while resting his wrist on the top of the body.

“Chuck Rainey was my idol, and I had just figured out how he patted his part on Aretha Franklin's Rock Steady. The bass sounded beefy in my headphones, so it worked. I wanted to add some development and make the part not sound so read, and Harvey was right with me.”

As the trumpet solo continues, he cuts back on his improvised part and introduces some 3rds (though Mason's active kick remains). “I felt I'd gotten to the highest energy level, so there's only one way to go, and that's to simplify – which, if done right, can take it to another place.”

The sax solo leads to a 16-bar percussion break, before a restatement of the entire head. The coda contains the closing lick – listen for the delay added to everyone's final note.

Lee, who cherishes his time carving new musical territory with the Breckers, advised, “After you get the gist of the written part, make it your own. We were fortunate that everyone felt the tempo, the groove, and the swing factor the same way, so just sit in pocket-central with us and have fun.”

Chris Jisi was Contributing Editor, Senior Contributing Editor, and Editor In Chief on Bass Player 1989-2018. He is the author of Brave New Bass, a compilation of interviews with bass players like Marcus Miller, Flea, Will Lee, Tony Levin, Jeff Berlin, Les Claypool and more, and The Fretless Bass, with insight from over 25 masters including Tony Levin, Marcus Miller, Gary Willis, Richard Bona, Jimmy Haslip, and Percy Jones.