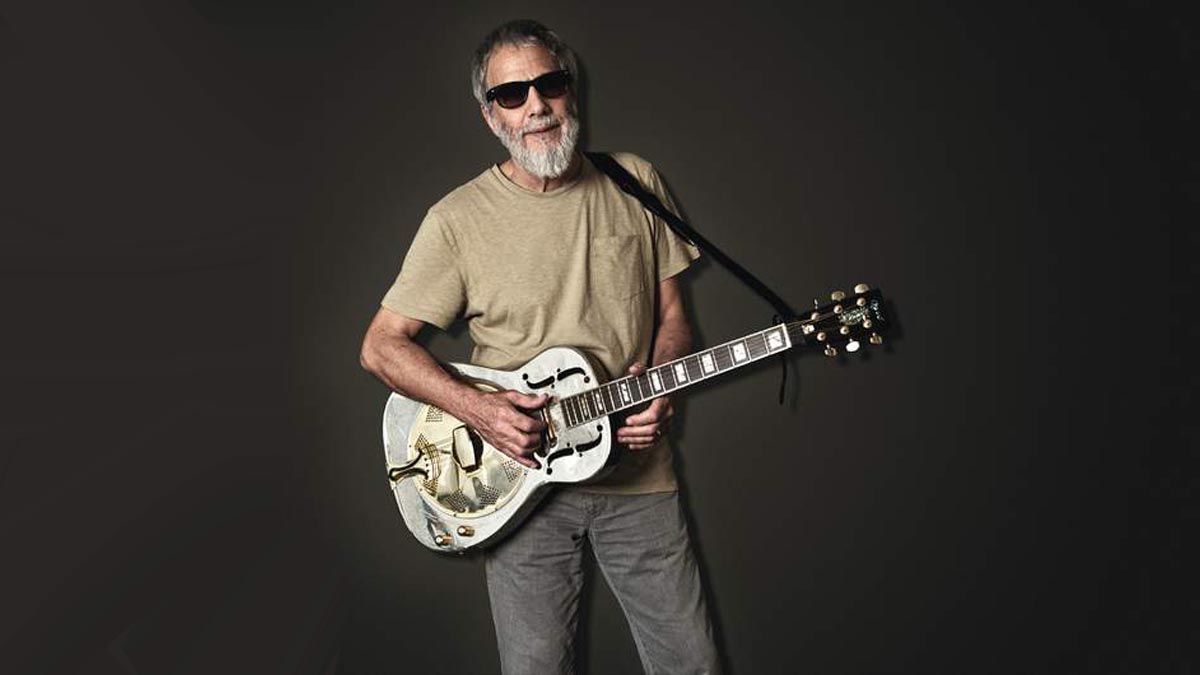

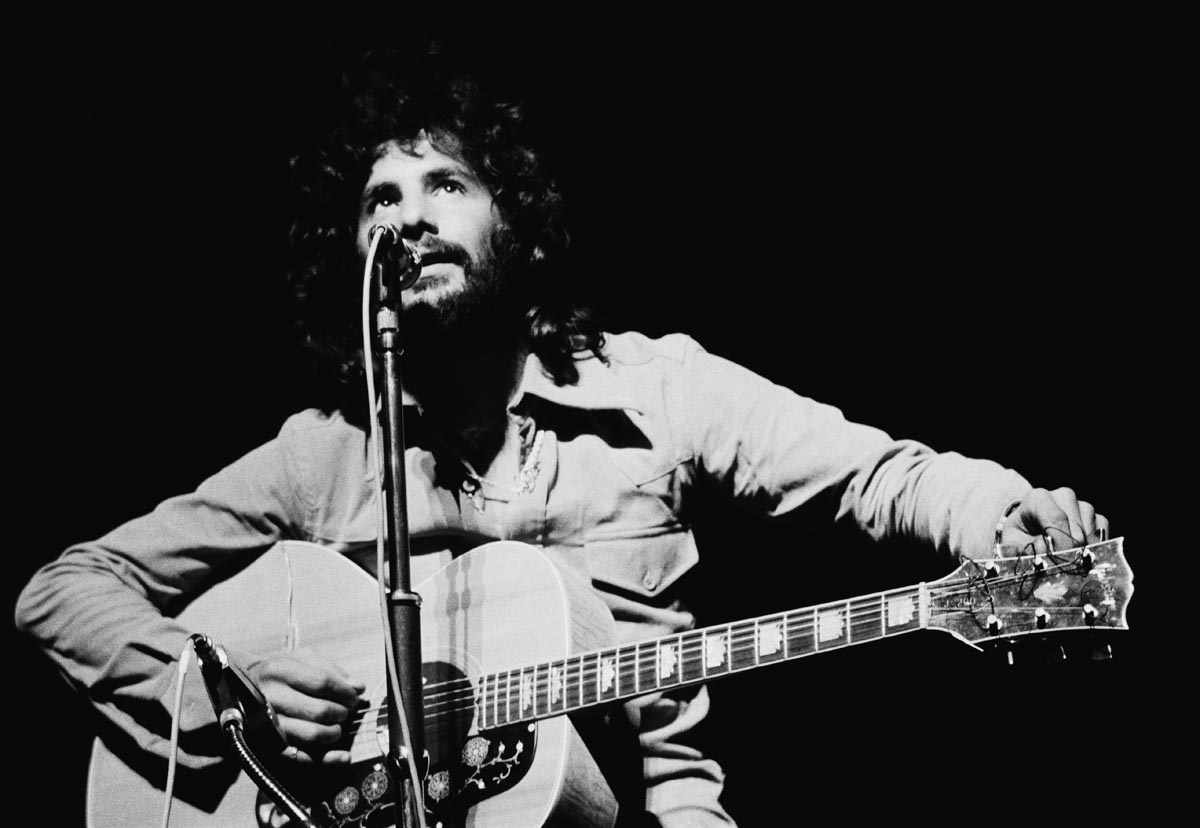

Yusuf/Cat Stevens: “Even today, I’m shy of playing in front of someone like Paul Simon because I never learned anything properly“

The legendary singer-songwriter looks back on a career that all started with a cheapo Eko and a cover of The Kinks...

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

He’s one of the most influential singer-songwriters in the world but left fame behind to complete a journey of spiritual growth.

Now he’s returned to music and joins us to talk guitars and songcraft – and explain why he decided to revisit his most famous album, Tea For The Tillerman, 50 years on.

Steep learning curve

“My first guitar was an eight-quid Eko made in Italy. It was pretty cheap and didn’t sound that great, either. All the problems you have learning the guitar were quadrupled by the fact it had such a high action, and I didn’t understand what strings to use or what gauge. So I was trying to keep my fingers down and make the notes as clear as possible.

“I was trying to do The Kinks’ You Really Got Me... But it was way too fast. My fingers just wouldn’t react quick enough… It was just too much of a challenge, so I gave it up. But then I came back to it and, when I did, I found I mastered it more easily. I don’t know why that happened. But the second time around I knew what I was doing. So that was the process that got me going towards playing the guitar.”

First good guitar

“I never had any doubt that I had something. It was just how long would the world take to catch up with me? Even though I wasn’t really that great at writing songs in the beginning, although I did have a few – in fact, The First Cut Is The Deepest was one of the earliest. So I had this confidence pretty much from day one… I’d written a few songs and I think my brother had seen the light, you know?

“A bulb flashed above his head and he said, ‘Hang on, this sounds good.’ And so he convinced my father to lay out 80 quid. And I bought myself a Hagström 12-string. I loved 12-strings because I was always a fan of Lead Belly. Those kind of early blues-folk songs were also relatively easy to learn as well. And the Hagström sounded loud, which was great.”

Coping with fame

“Basically, like most artists, I was kind of an introvert. And to actually stand up and do this thing in front of other people – and be as good as you are when you’re all alone – is not that easy to achieve. There are so many faces looking at you, expecting you to be great and you have to be great at that moment. The challenge was enormous, so I hated it. I hated it.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“Because after cutting my teeth in the folk clubs and just doing [my music] quietly, occasionally taking the mic and doing a little song, the next big step was being seen by about three million people on television, live on Simon Dee’s show [Dee Time]. I could have died – but I had to go through with it. So you can imagine that the trajectory that I was on was just like ‘Zap! Boom!’ – and suddenly I was there.”

Developing a voice on guitar

“Early on, I was impressed by the Bert Jansch clique: John Renbourn, Davey Graham… I remember that everybody could play Anji [by Davey Graham] and I loved that kind of folk thing. But, of course, The Beatles were absolutely dominating everything for me: the skill of the writing. The problem was I never had an electric guitar, so it was always acoustic. So I tended to write on an acoustic and I was always more of a rhythm guitarist than a solo player. I couldn’t do that.

As you experiment with chords, it starts to get boring when you can only do simple strumming. And that’s where fingerstyle does the job

“As you experiment with chords, it starts to get boring when you can only do simple strumming. And that’s where fingerstyle does the job. You’re on a chord, it’s a simple thing, you’ve got the shape right but now you can make it sing in a different way. I never really learnt the intricacies of fingerpicking properly.

“I mean, even today, I’m shy of playing in front of someone like Paul Simon because I never learned anything properly. But the way I did it was kind of unique and that’s why I suppose it works in my songs.”

Life-changing illness

“Getting sick [with tuberculosis] completely changed the course of my life. I mean, up to that point, I’d been living kind of a shell of a life. I had not really developed an identity. And I’d been kept in my [early career signature-garb of] tuxedos, if you like, by the business and the agencies around me at the time.

“And so this was a chance for me to break free of the image and to kind of find myself. And I was looking very, very deeply into my psyche of who I was… and that spiritual exploration began in the hospital.

“But the illness didn’t stop me [writing] and, in fact, I started writing very soon. One of the things I wrote around then was a song called The View From The Top, which is a very sad song. It was saying, ‘Why am I always trying to be like somebody else?’ I was really digging into the question of identity. And so that is very, very important.”

Who are you?

“I had to go and convalesce for a long time. They told me, ‘Don’t work for a year.’ I can’t for the life of me remember how it came about, but one of the first gigs I did after the hospital thing was as the support act for The Who at the Roundhouse.

“By that time I had got myself an electric guitar – a Gibson 355 or 335, I think – and I had my little Fender amp and I’d written some really wonky songs… it was a blip [laughs]. But I was still looking for the right moment for things to happen and for me to find out what I wanted to do next.”

Blessed Isle

“Signing to Island Records was the greatest liberating opportunity I ever had in my career, certainly up to that point. It was like: now you can do whatever you want. And Chris Blackwell [Island’s founder] was absolutely bowled over by my songwriting, because by that time I’d written things like Father And Son and Where Do The Children Play? and he’d listened to quite a few of them.

“He introduced me to [Yardbirds founder and producer] Paul Samwell-Smith and there was already some history there, because I’d been in the 100 Club and danced to his band when they were playing.

“So Chris gave me all the freedom I wanted and – not only that – when it came to the record cover, he said, ‘Well, you’re an artist – why don’t you draw it?’ I couldn’t have asked for anything more! He gave us the freedom to do things like that. He got a little bit gripey when we overspent by more than £3,000 on the first album, though…”

Mona Bone Jakon

“I think originally it was intended that Jon Mark should be the guitarist on my album Mona Bone Jakon, but then he couldn’t do it. So his friend Alun Davies came along in his place. And we got on just so perfectly because he had this intricacy that could fill out all the gaps in my chord playing, and he gave them another dimension. And so it was just a perfect partnership.

“You can hear the beauty of that relationship in the chords of Lady D’Arbanville. That song was a little bit influenced by Peter Green and his track Oh Well – and in more than one way, in fact, because Peter Green was one of those people who actually walked away from the business at one point.

“It was pretty impressive to me that somebody could do that. I ended up drawing a dustbin as the cover design. I think I was trying to just say, ‘Look, this is raw, this is grit-level, so if you’re going to listen to this, get ready.’”

Pop Star

“Once you’re taken as a model or as kind of an idol, you’ve got a lot to live up to. You’ve got to be bigger than you are. And that’s impossible to sustain. At some point, you’ve got to find your feet where you feel comfortable. And that’s why I think, when

“I wrote the song Pop Star, I kind of knew it was a temporary thing that while it was good, it was good. My goal was much higher than just the charts, but it was the only way I knew how to express myself, so that’s what I did. I’m not belittling music, it was everything to me at that time.”

Wild World

“Wild World was a song that I wrote coming out of a relationship with my girlfriend at the time, Patti D’Arbanville. It had ended, and I wished her well, which came out as a kind of nice message... But I always felt the song was a little bit too commercial, so when they were talking about me releasing it, I said no.

“But I know that Chris Blackwell loved the song and he wanted Jimmy Cliff to do it. So I produced that song for Jimmy and he had a hit with it and it went very well, and in America they were screaming for me to release my version of it. I said okay, but for me it was a little bit like the kind of commercial song that I used to write in the early days of my 60s career. So I was slightly averse to that being representative of me.

“By comparison, Miles From Nowhere from Tea For The Tillerman represented much of my journey and my placement in this universe. We all come in here [to the world] and we don’t quite know why we’re here, but we know that we’ve got to get somewhere and that place has got to be better than where we are.”

Game-changing Gibson

“I really turned a corner when I got my hands on a black Gibson Everly Brothers J-180. It was my favourite guitar, I just loved it. It was really dynamic and it had a very easy action, very thin neck. It was just such a beautiful instrument, too. But, of course, it didn’t have any [means of] amplification, and so here we get to the problem.

“Because in the old days, how do you mic an acoustic? There was always a horrible, horrible ever-present feedback. You couldn’t really play that loud. That guitar got supplemented later with things like the Ovation – but the Ovation was just a necessity because it really wasn’t a guitar that you wanted to play.”

Foreign affair

“The album Foreigner kind of describes itself. It was my wanting to escape the spotlight and the image I’d been cast into. It was running away with me. The success was so big, so overwhelming. My last album before that, Catch Bull At Four, went to No 1 and suddenly everybody was full of expectation. And I hadn’t found myself.

“So I decided to do something completely different – Alun was not there, Paul wasn’t there… I just went to Jamaica and recorded in the heat of everything. I recorded all these parts of songs that I had written at some point and kind of threaded them together in a way that made sense to me, and that became the Foreigner Suite.”

Finding faith

“People asked me how could I leave and just give up music, but it was because I’d actually found what I was looking for [with religion]. My goal was to find that place where I understood what life was about. I had to go through a lot of adventures, in a way, to get to that point. But when I did, I thought, ‘Well, this is great.’ You get to a point where you’ve written songs and you’ve got to be inspired to write another one.

“By that time, I was just so excited: I was learning about so many other things. I got married and had so many wonderful opportunities to do things I’ve never done before because I was always on the road or in the studio. And this was freedom: the freedom to do whatever I wanted in life, like have children. So all these things took over and I just gave up my guitar and said ‘Well, this is it.’ Until I see a way forward, this is what I’m going to do.”

Peace Train

“Why I came back to making music is to try to make sure that people understood that I’m still who I am. You know, I haven’t really gone away from my ideals – peace is the first stop for me and it’s the last stop. When you’ve got something to say, you should say it. And music is a way of making candid your thoughts, even your dreams, your hopes, your fears. Everything can be said in music.”

- Yusuf/Cat Steven's Tea For The Tillerman 2 is out now via A&M.

Jamie Dickson is Editor-in-Chief of Guitarist magazine, Britain's best-selling and longest-running monthly for guitar players. He started his career at the Daily Telegraph in London, where his first assignment was interviewing blue-eyed soul legend Robert Palmer, going on to become a full-time author on music, writing for benchmark references such as 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die and Dorling Kindersley's How To Play Guitar Step By Step. He joined Guitarist in 2011 and since then it has been his privilege to interview everyone from B.B. King to St. Vincent for Guitarist's readers, while sharing insights into scores of historic guitars, from Rory Gallagher's '61 Strat to the first Martin D-28 ever made.