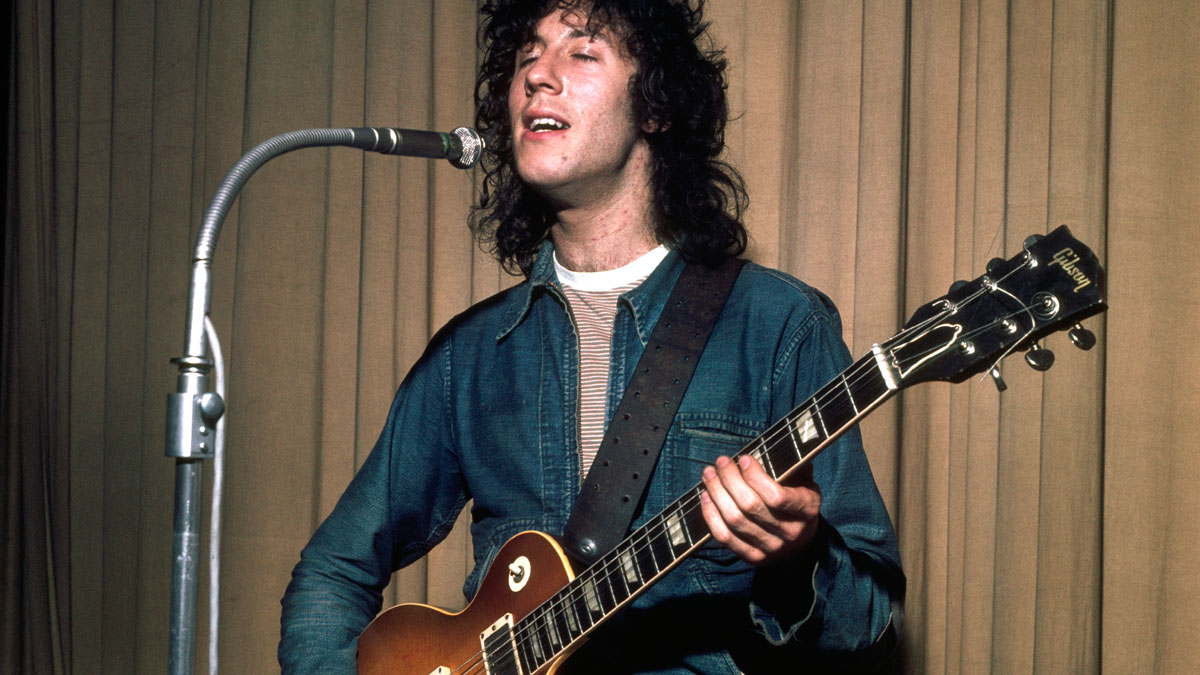

The story of Peter Green, one of British blues' most mythologized - and influential - players

We look back at Greeny's trailblazing tenures in The Bluesbreakers and the Mac, 50 years on....

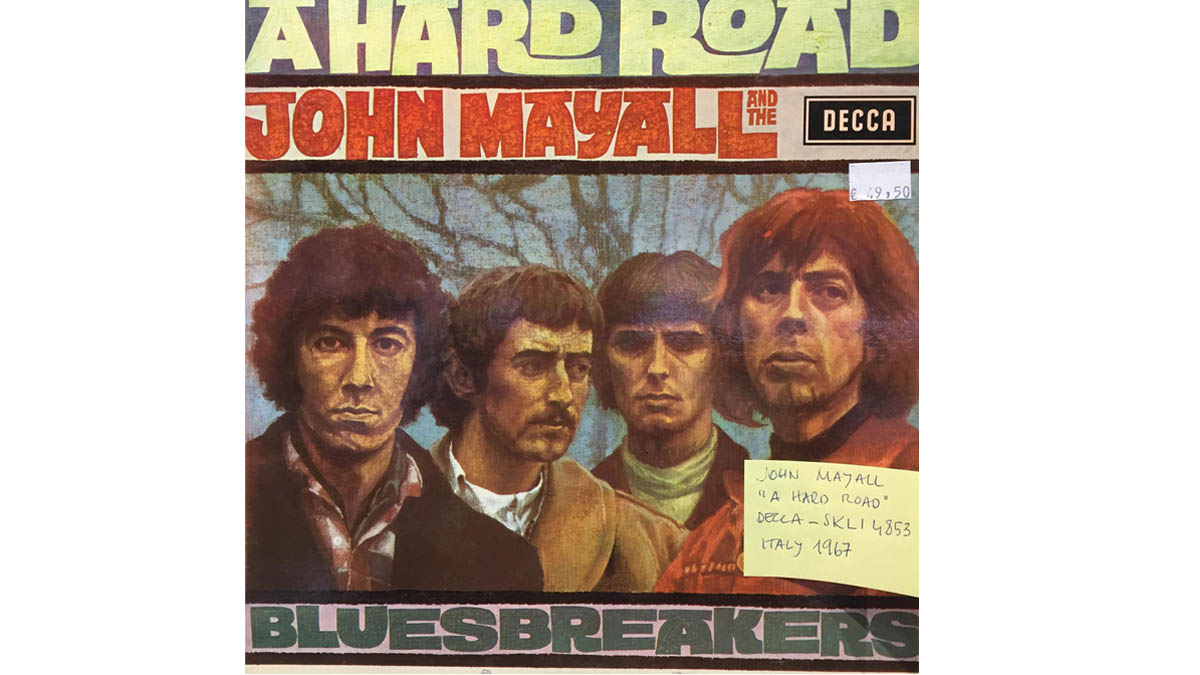

It was October 1966, and God had gone missing. Scanning the Decca Studios in North London as John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers set up to record A Hard Road, producer Mike Vernon felt a sense of rising panic.

“I said to John, ‘Where’s Eric Clapton?’ Mayall says: ‘He’s not with us any more, but don’t worry, we’ve got someone better.’ I said, ‘You’ve got someone better – than Eric Clapton?’ John said, ‘He might not be better now, but in a couple of years, he’s going to be the best.’ Then he introduced me to Peter Green.”

Vernon’s incredulity made sense. After all, this was Eric Clapton: pack-leader of London’s fretting classes, proclaimed as ‘God’ in graffiti all across town, whose precocious fingers had shot molten soul over Bluesbreakers cuts like Hideaway and Little Girl from that summer’s scene-igniting ‘Beano’ album.

The fact that Beano’s official title gave him top billing – Bluesbreakers With Eric Clapton – spoke volumes about the hotshot guitarist’s pulling power. Now he was gone, replaced by a spring-haired cockney interloper.

The swap seemed absurd, like a Sunday league nonentity pulling on George Best’s hallowed number seven shirt and running out for United. Only Mayall was unruffled, showing the quiet confidence of a man with an ace up his sleeve. Bringing in Green, he reflected, decades later, “was a no-brainer”.

Peter had pestered John to employ him, often turning up at gigs and shouting that he was better than whoever was playing that night.

Eric Clapton

Born in London's working-class Bethnal Green on 29 October 1946, Peter Allen Greenbaum’s early life echoed that of his fellow British Invaders. Like his peers from that golden generation, he devoured the import vinyl that trickled over from the States, thrilling to the primal touch of US titans like Freddie King, Otis Rush, John Lee Hooker, Buddy Guy and – perhaps most palpable in his own playing – the one-note master, BB King.

Green had tried guitar, but ended up slogging across London, bass in hand, keeping his head down in also-ran acts like Peter B’s Looners. It was Clapton, he recalled, who changed his trajectory. “I decided to go back on lead guitar after seeing him with the Bluesbreakers. He had a Les Paul, his fingers were marvellous. The guy knew how to do a bit of evil, I guess.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

By his own admission, Clapton was a flake who regularly ducked shows, and when Mayall recruited deps, Green showed them no mercy. “Peter had pestered John to employ him,” noted Clapton, “often turning up at gigs and shouting that he was better than whoever was playing that night. I got the impression he was a confident person who knew exactly what he wanted.”

When Clapton took a booze-soaked holiday in Greece in August 1965, Green got his chance, only to be left fuming when the prodigal son returned to reclaim his gig. But by summer 1966, when Clapton quit for Cream, Green became a permanent fixture, quickly silencing the early catcalls – “Where’s Eric?” – with his magic touch.

Playing fast is something I used to do with John when things weren’t going very well

Peter Green

“What I remember about those concerts is that nobody was calling for Eric,” remembers Tom Huissen, the Dutch fan who released an album of Green-era bootlegs in 2015. “They accepted Peter straightaway. The way he played – it was just phenomenal.”

Green’s mastery of mood meant he could shine on live material spanning from Otis Rush cuts like So Many Roads, through R&B floor-shakers like Johnny ‘Guitar’ Watson’s Looking Back, to T-Bone Walker’s languorous Call It Stormy Monday. He could certainly play blazing, visceral flurries of notes, but to Green, doing so was an admission of defeat.

“Playing fast is something I used to do with John when things weren’t going very well,” he reflected. “But it isn’t any good. I like to play slowly and feel every note.” Speaking to Christopher Hjort for the notes of last year’s Fleetwood Mac: Before The Beginning boxset, Vernon also noted that Green resisted the era’s growing vogue for overdrive. “He loved the sound of the guitar pure, without too much distortion, and made the notes sing, rather like BB did.”

It was this same ethos that Green brought to A Hard Road’s sessions, which alternately groans with some of his most fiery and sensuous playing. Back in 1998, he would give a characteristically modest interview to Guitarist, shrugging that “I didn’t really know what I was doing. I used to dash around on stepping stones. ‘Safe’ notes, y’know?”

Released on 17 February 1967, this album gave the music world its first opportunity to hear Peter Green in full flight.

Tracks such as The Stumble and the glorious reverb-drenched The Supernatural became instant classics, leaving little doubt among Bluesbreakers fans that Peter Green was a worthy replacement for Eric Clapton in the band.

Yet Green’s towering performances on that 1967 album beg to differ, whether on the weeping bends of Someday After A While (You’ll Be Sorry) or the intense sustained notes of The Supernatural. And even if speed wasn’t his style, the guitarist would sometimes relax his principles, as on showboat instrumental The Stumble: less lauded than Clapton’s Hideaway, perhaps, but easily its equal for chills.

The Bluesbreakers seemed the perfect home for a player of Green’s persuasion. But even as A Hard Road reached UK No 8 in February 1967, the guitarist was restless.

Fleetwood Mac was a bit of an experiment to start with. I wouldn’t have been surprised if it had failed

Peter Green

As he told Norman Jopling: “It was becoming less and less of the blues. We’d do the same thing night after night. John would say something to the audience and count us in, and I’d groan inwardly.”

According to then-girlfriend Sandra Elsdon, Green was even chewing over a move to the motherland (“He was into Chicago blues and just wanted to be immersed in it”), until the plan was killed by Mayall’s flatmate Marsha Hunt. “I could only imagine this small temperate London boy getting his ass kicked in Chicago,” she remembered. “I put him off in no uncertain terms.”

Even so, Green was not long for the Bluesbreakers line-up. The original members of Fleetwood Mac remember his approach as being tantamount to a press gang (“Peter asked if I wanted a drink,” recalled guitarist Jeremy Spencer, “and as we stood by the bar, he talked as though I was already in it”) and in late-summer 1967, Vernon unlocked Decca Studios under cover of darkness for a secret session by the nascent line-up, completed by drummer Mick Fleetwood and original bassist Bob Brunning (shortly replaced by John McVie).

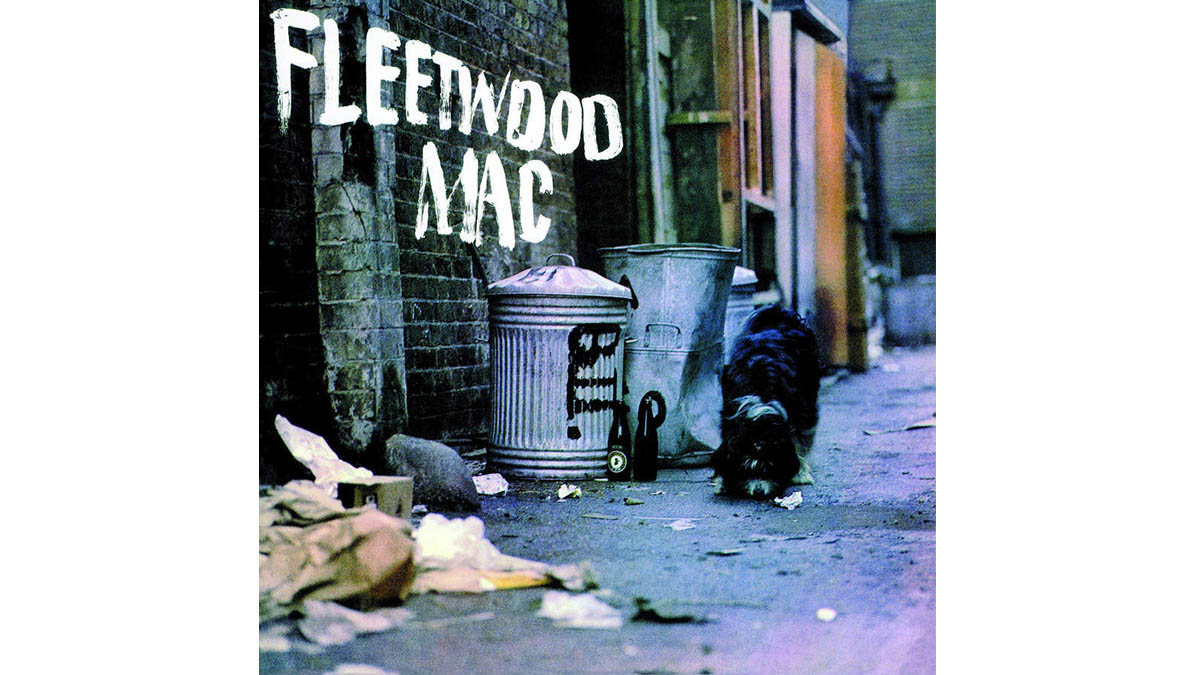

Just a year after Peter’s recording debut with The Bluesbreakers, Fleetwood Mac released their first album in February 1968. It went on to reach No 4 in the UK album charts

“Fleetwood Mac was a bit of an experiment to start with,” Green noted. “I wouldn’t have been surprised if it had failed.”

Given Green’s profile, the subterfuge couldn’t last. Soon enough, the music press was buzzing (Melody Maker: “A new Cream-type group is being formed by ex-John Mayall guitarist Peter Green”) and Mayall graciously accepted the loss of a second guitar god in as many years. In truth, Melody Maker was off the mark.

As the debut album reached UK No 4, a less questing bandleader might have been satisfied to stick to the formula and ride the prevailing appetite for electric blues. But, as ever, Green was thinking bigger.

The irony is that these funny little English dudes reconstituted an artform that was all but dead – nobody gave a shit about it in America

Peter Green

Unlike the psych-tinged and jazz-inflected Cream, Fleetwood Mac’s dedication to the true, deep blues was unwavering – even if they did occasionally give the stage to Spencer’s 50s rock ’n’ roll pastiches.

“The irony is that these funny little English dudes reconstituted an artform that was all but dead – nobody gave a shit about it in America – and served it back to them,” wrote Fleetwood in his Love That Burns book. “We helped save something that was all but thrown in the dustbin.”

For purists, the band’s self-titled debut – recorded live and informally christened ‘dog and dustbin’ after its sleeve art – was a treasure trove, with Green originals jostling with standards by Robert Johnson and Elmore James.

Revisit the enigmatic, echo-clad guitar leads of I Loved Another Woman, for example, where Green had rarely sounded so supple and emotive.

“It really holds up, when you listen to some of that early stuff,” writes Fleetwood. “I mean, Peter was such an extraordinary player, so sensitive and mature.”

The burden of our success haunted him. Peter thought it was all bullshit and was convinced that people never really liked him

Mick Fleetwood

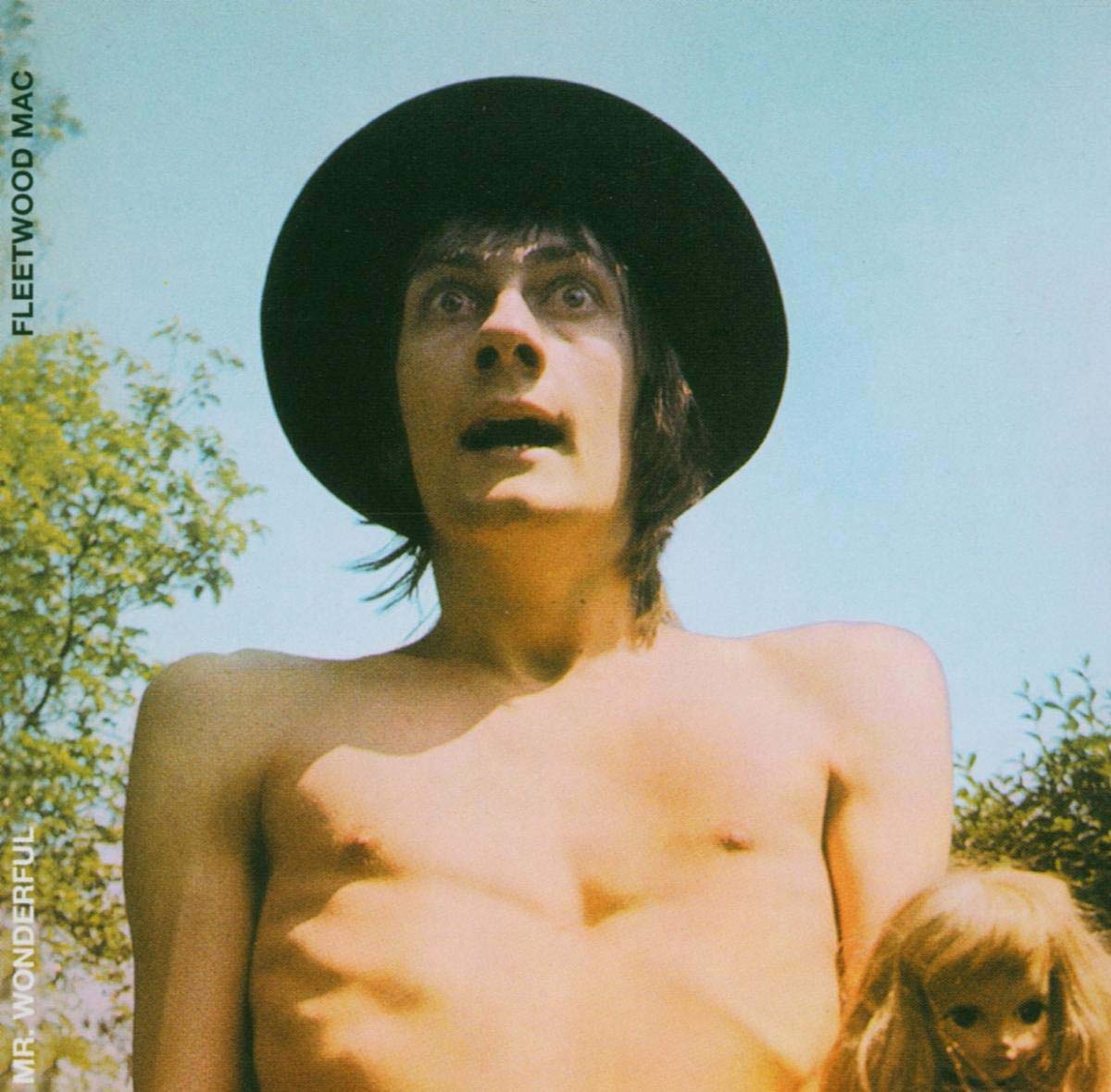

After an underwhelming follow-up album in August 1968’s Mr Wonderful, the recruitment of cherubic guitarist Danny Kirwan was a catalyst, prodding Green from tired 12-bars towards offbeat textural work, more like that year’s earlier single, Black Magic Woman. “That was the song,” noted Vernon, “that proved that Peter was not only just a really good songwriter, he was an exceptionally good songwriter.”

Green didn’t share that opinion: he had confidence in his playing, but writing was uncharted territory (“I was forced into songwriting,” he told us in 1998. “I’m not really a songwriter”). But a breakthrough came when he shook off the prescriptive influence of the blues pioneers and accepted the genre was defined more by feel than formula.

“To my mind,” Green told journalist Ian Middleton, “a blues doesn’t have to be a 12-bar progression. It can cover any musical chord sequence. To me, the blues is an emotional thing. If a song has the right emotion then I accept it as a blues.”

With his antennae up, and attuned to the more experimental writing of bands like The Beatles, the early Mac’s most iconic song was born. Albatross was a swooning, swooping, pulsing instrumental, with Green draping stately guitar lines over a tapestry of overdubs.

Fleetwood Mac – Mr Wonderful (1968)

Fleetwood Mac’s second release came just six months after the first, in August 1968, and was augmented by a horn section.

Fleetwood Mac – Black Magic Woman (1968)

Allegedly Peter wrote Black Magic Woman about his girlfriend at the time. Sanatana’s cover was a bigger hit two years later.

Fleetwood Mac – Then Play On (1969)

Danny Kirwan joins the Fleetwood Mac line-up for their third recording. It was to be Peter’s last with the band.

“It was a brand-new Strat,” Green told David Mead in 1995. “We hired two for the recording and that was one of them. There’s a Les Paul on there as well, though. But the chords and the main melody are on a Strat with the high melody parts on the Les Paul. Danny plays the harmony parts. There are two bass guitars on there, too.”

Such ambition was lost on CBS executives, while even Fleetwood fretted that Albatross was “a little light in the loafers” for their blues hardcore. But Green persisted, and when the song sailed to UK No 1 in December 1968, it set in motion a career-best run of creativity.

In 1969 alone, Green delivered the glistening Man Of The World and schizophrenic folk-rocker Oh Well (both UK No 2 singles), before third album, Then Play On, made UK No 6 and announced a musical mind fusing everything from tape echo to the classical influences of Vaughan Williams’ The Lark Ascending.

“One can only imagine,” mused Fleetwood, “what he’d have created if he had continued on that track.” And yet, if you peered a little closer, it was clear the first incarnation of Fleetwood Mac had already peaked.

Green was unravelling, leaving lyrical clues to his state of mind (‘I just wish I’d never been born,’ runs Man Of The World, while Love That Burns begs: ‘Please leave me now in my room to cry’). Then there was his final composition, The Green Manalishi (With The Two-Prong Crown), examining Green’s struggles with fame, fortune and imposter syndrome, his spooky guitar tone signposting a man on the brink.

“The burden of our success haunted him,” noted Fleetwood. “Peter thought it was all bullshit and was convinced that people never really liked him.”

In April 1970, an NME interview revealed the extent of Green’s burnout. “I feel it is time for a change. I want to change my whole life, really, because I don’t want to be at all a part of the conditioned world, and as much as possible, I am getting out of it.”

A collection of early live performances and sessions, this is a fantastic insight into the early days of Fleetwood Mac; it’s clear why players such as Gary Moore and BB King loved Peter’s playing so much.

Particular highlights are Worried Dream, Instrumental and a live version of Albatross. There are plenty more tracks on here to check out, but these are a great place to start.

Get out of it he would, in both senses. In early 1970, after a disastrous LSD dose at a Munich hippie enclave, Green’s fragile headspace shattered entirely, leading the guitarist to quit the band and tumble into an existence mostly chronicled by troubling newspaper headlines.

Decades later, when mercifully recovered enough to play with his underrated Splinter Group, Green couldn’t form a cogent argument for his actions in those last chaotic days of Fleetwood Mac. “I don’t really know why I left the group in the end. I think it was just because I wanted to do things for free. I knew that people looked at me like I was in a dream. I could tell that, even at the time…”

Green’s fall from the top table of British blues is often viewed by connoisseurs as a maddening waste of talent, his early promise only half-fulfilled at best. Perhaps, but rather than pine for what might have been, it’s surely better to treasure his output from that magical era and celebrate the genius that fired the world’s imagination, however briefly.

As Fleetwood once told this writer: “I’ve just learnt that Peter’s journey took him where he is. After a while, you just have to accept it…”

Henry Yates is a freelance journalist who has written about music for titles including The Guardian, Telegraph, NME, Classic Rock, Guitarist, Total Guitar and Metal Hammer. He is the author of Walter Trout's official biography, Rescued From Reality, a talking head on Times Radio and an interviewer who has spoken to Brian May, Jimmy Page, Ozzy Osbourne, Ronnie Wood, Dave Grohl and many more. As a guitarist with three decades' experience, he mostly plays a Fender Telecaster and Gibson Les Paul.