The Hendrix chord: learn Jimi Hendrix's favorite 7#9 shape

Ever wondered how players like Jimi Hendrix and Grant Green blur the distinction between major and minor with such bluesy ease? Let us show you how it's done...

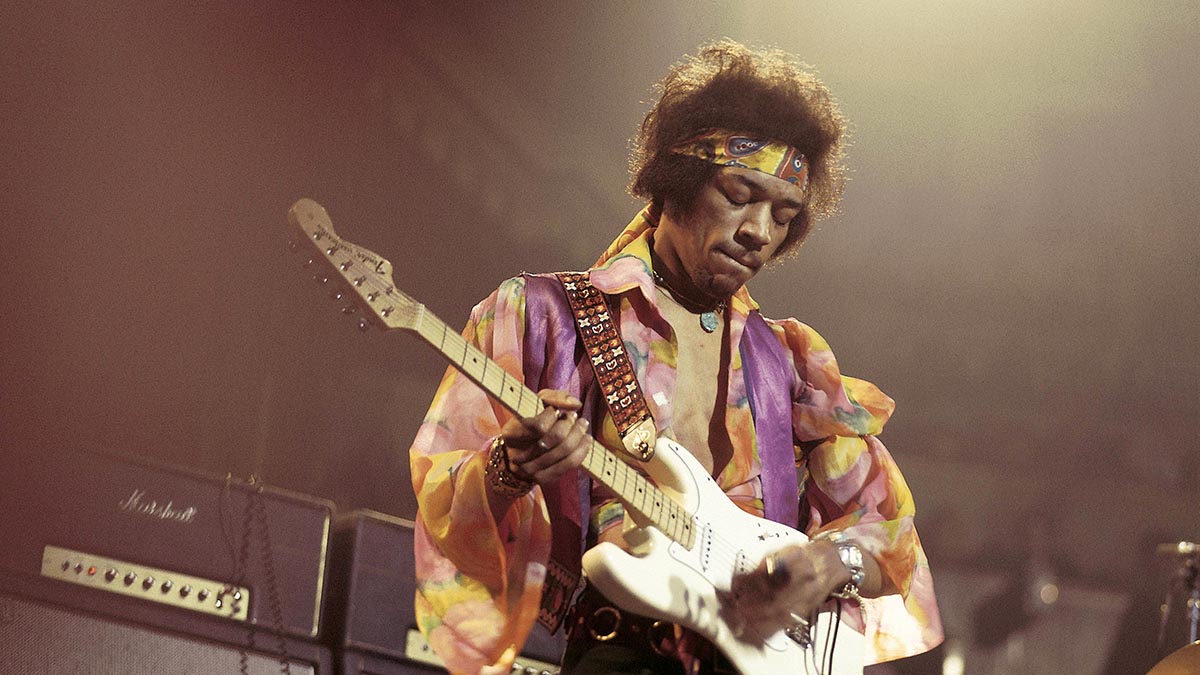

Jimi Hendrix was undoubtedly one of the most significant musicians of the last century. For many, he was the ultimate electric guitarist, with an innate understanding and assimilation of previous generations of guitar masters, along with a clear vision of how he could interpret this music in his own uniquely personal and dynamically charged way.

While Hendrix’s peers such as Jeff Beck, Eric Clapton and Jimmy Page were equally significant and influential to the guitar world at large, Jimi’s considerable talents earned him one unique award, rather like a Heritage Blue Plaque of guitar technique, the ‘Hendrix Chord’.

Take a listen to Hendrix tracks such as Foxey Lady, Purple Haze, Crosstown Traffic and many more and you’ll hear a consistent use of this ‘Hendrix’ chord, a Dominant 7th with added raised 9th degree, labeled as 7#9.

While this chord had been around for quite a while, Hendrix assimilated this sound so naturally and completely into his compositional style that he literally made it his own.

If we look at the notes independently, taking C7#9 as our example, we can see a root (C), Major 3rd (E), perfect 5th (G), flattened 7th (Bb) and raised 9th (D#). This raised 9th could also be enharmonically considered as a Minor 3rd (Eb), so with this in mind our chord now contains attributes of both Major and Minor tonalities, so is perfect for implying that harmonic ambiguity that we find in blues, a style that Jimi evidently knew very well.

Rather than employ these 7#9 sounds in a functional capacity, where C7#9 could be considered an event in motion, part of a chain treating our 7#9 as the V7 of a forthcoming resolute I chord, either F Major, Minor or Dominant, Jimi uses these sounds in either static or parallel forms, treating each 7#9 as an independent sound in and of itself, and makes great use of the dual harmonic potential to see each from either the Dominant Major or largely Pentatonic Minor perspective.

The purpose of this lesson is to explore the 7#9 sound in both harmonic and melodic settings. The musical examples that follow are divided into five sections, starting off with a look at the most common voicings.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

We also consider how the #9th sound can be used in Dominant situations to create single-note riffs, double-stop and chord fragments and also in classic lead guitar lines. We’ll be considering 7#9 musical examples found in the playing of jazz masters such as Grant Green, rock and roll legends like Chuck Berry and also Hendrix’s peers and contemporaries such as Eric Clapton and Robben Ford.

We round up our exploration of #9th Minor-against-Major action with a cohesive study in two parts. Based around a 12-bar Hendrix inspired psychedelic blues rock progression in C, the first chorus is devoted explicitly to rhythm guitar and uses a combination of 7#9 voicings peppered with single-note riffs, while for the second chorus it’s soloing time.

Although none of the lines and licks here are too difficult to get your fingers around, really consider how you approach the delivery and commitment to each phrase; strive for a confident and bold attack and aim for the most singing and expressive tone possible. For inspiration, consider watching some live footage of Jimi in action and revel in just how glorious he makes everything sound. As always, enjoy.

Jimi’s Got Rhythm

While it’s completely understandable that much of the analysis of Hendrix’s playing is focused on his incendiary lead playing, he was also an incredible rhythm guitarist, expertly mixing genres to create a cohesive and highly original sound that was stylistically authentic, rooted in tradition and also unique and forward thinking.

Serving his apprenticeship on the ‘chitlin’ circuit’ backing artists such as Wilson Picket and Sam Cooke and with stints in the backing bands of both Little Richard and Curtis Knight, Jimi certainly did his homework.

Hendrix had the ability to connect chords, melody and even bass parts together to create a huge sound that was both powerful and sophisticated

His groundbreaking rhythm playing with both the Jimi Hendrix Experience and Band of Gypsys saw him expertly mix Chicago blues with hard rock, funk with jazz and even R&B was given the psychedelic once-over. It’s perfectly clear that to Jimi it was all just music and any genre was fair game for his magical touch.

Frequently blurring the distinction between lead and rhythm, Hendrix had the ability to connect chords, melody and even bass parts together to create a huge sound that was both powerful and sophisticated in equal measures. Ensure in your own playing that you give this crucial aspect of your sound the respect and attention that it truly deserves.

Get the tone

By today’s standards, Jimi’s rig was simple: a Strat into a wound-up valve amp with wah, fuzz and some form of ‘vibe’ effect will place you in the right area. For today’s examples we’d suggest a clean or slightly overdriven rhythm tone, either by setting the amp clean or by dialling down your volume at the guitar.

You can choose to add gain for the lead examples by cranking the volume back up or by adding an overdrive, fuzz or distortion pedal.

Example 1. 7#9 voicings

We begin by defining a collection of some of the most popular voicings for this chord, starting with Hendrix’s favourite shapes, repositioned through each four-string grouping to outline C7#9 (C-E-G-Bb-D#), although you might notice in these shapes the 5th (G) is not present.

We choose a restricted fretboard area to spell out a I-IV-V in C, but with 7#9 chords, giving us C7#9, F7#9 and G7#9 respectively and flesh this out with a musical example. In 1c) we define some other common shapes for this chord courtesy of Stevie Ray Vaughan, with the 5th now present, Grant Green and George Harrison.

This is one of the legendary ‘Gretty’ voicings, taught to George by music shop assistant and jazz aficionado, Jim Gretty while perusing guitars at Hessy’s Music in Liverpool as a lad.

Example 2. #9 in other locations (enharmonic respellings apply)

In this example we’re looking at ways to define the #9th sound in a Dominant setting with single-note riffs and motifs. For reading ease we’re using the easiest enharmonic spelling here, as much of this material amounts to C Minor Pentatonic (C-Eb-F-G-Bb) against C7 (C-E-G-Bb).

You’ll note that almost every Eb (or to be pedantically accurate, D#) is bent ever so slightly sharp to allude to the Major third without ever quite reaching it (the blues ‘curl’).

Example 3. Double-stops

We can use the #9th sound in double-stops or small chord fragments to great effect, once again implying a sound that falls between the cracks.

Here we see a collection of four common moves that employ at least two notes played together starting with a Grant Green idea, moving through licks from Buddy Guy and Chuck Berry. Our final T-Bone Walker idea combines the Minor 3rd/#9th against a Major sound with an equally mournful b5th to 5th resolution (Gb to G).

Example 4. Mixing Minor and Major 3rd

In this example, we’re considering some of our single-note lead guitar options, so we begin by defining a pair of scale choices, specifically C Minor Pentatonic (C-Eb-F-G-Bb), albeit juxtaposed against C7 and with each b3rd/#9th curled upwards slightly, and then a hybrid scale that contains both Major and Minor 3rds (Eb and E: C-Eb-E-F-G-Bb).

You could see this as the logical combination of C Minor Pentatonic with a C7 arpeggio (C-E-G-Bb). We round this example off with a pair of choice phrases using each scale option courtesy of Robben Ford and Eric Clapton.

Example 5. Cohesive Piece

We conclude this look at the 7#9 sound with a cohesive study set around a Hendrix inspired psychedelic blues in the key of C, using 7#9 chords exclusively.

The first chorus is devoted to rhythm, with full chords used to punctuate single-note riff ideas that blur the lines between Minor and Major by using elements of the Minor Pentatonic juxtaposed with the associated Major 3rd for each harmonic event – ie, each chord change.

The second time around we crank the gain level up considerably and negotiate the same harmonic terrain with a selection of stylistically appropriate lead lines, again targeting the ambiguous #9th frequently and also incorporating other appropriate devices such as unison bends, double-stops and octaves.

John is Head of Guitar at BIMM London and a visiting lecturer for the University of West London (London College of Music) and Chester University. He's performed with artists including Billy Cobham (Miles Davis), John Williams, Frank Gambale (Chick Corea) and Carl Verheyen (Supertramp), and toured the world with John Jorgenson and Carl Palmer.