A Tribute to Cliff Gallup’s Legendary Flash

The Gene Vincent and His Blue Caps guitarist defined the classic rockabilly guitar sound.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Gene Vincent and His Blue Caps epitomized rockabilly’s iconic image, with their leather jackets, ducktail hairstyles and kick-ass-and-take-names personae. The band also introduced one of the most adept, versatile and influential electric guitarists of his generation: Cliff Gallup.

Born in 1930, Gallup was 26 when he joined up with Vincent, a wild young singer from Norfolk, Virginia. In May 1956, as the brief but volcanic rockabilly craze was peaking, Vincent was invited to record in Nashville under the guidance of veteran producer Ken Nelson.

Nelson had session pros (including studio guitar phenomenon Grady Martin) standing by, in case the energetic but green Blue Caps failed to deliver. But from the moment Gallup launched into “Race with the Devil,” it was clear that he was an extraordinary guitarist and unique stylist in his own right.

The Nashville sessions produced Vincent’s biggest hit, “Be-Bop-a-Lula,” and in the process Gallup defined the classic rockabilly guitar sound with his bright, clean tone, augmented by a healthy dose of slapback delay. His setup featured a Gretsch Duo-Jet with DeArmond pickups, Bigsby vibrato and heavy, flatwound strings, most likely played through Martin’s Standel amp.

Gallup combined fast chromatic phrasing reminiscent of Les Paul and a Chet Atkins–inspired hybrid picking style (flatpick plus metal fingerpicks on his second and third fingers, with his fourth finger working the Bigsby tremolo bar), but the spontaneous, imaginative results were entirely his own.

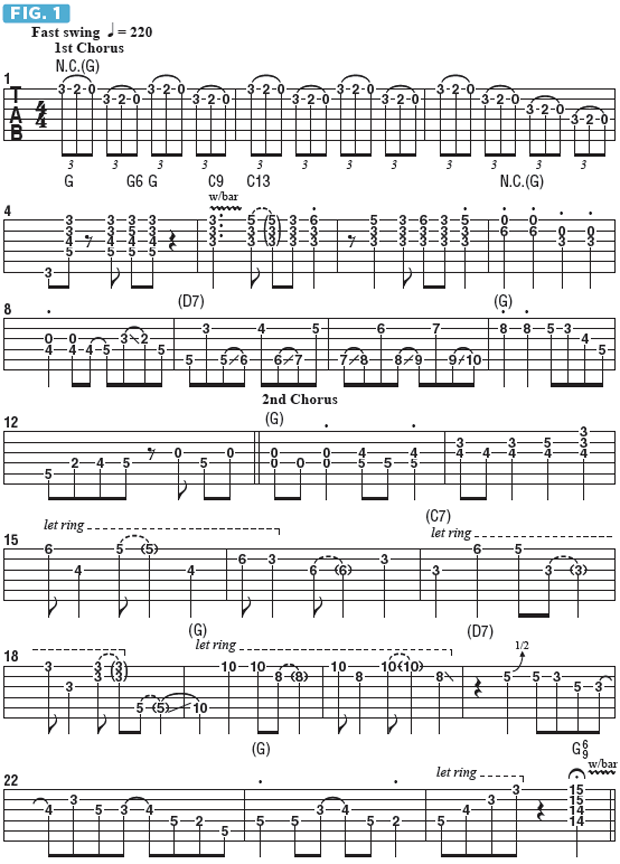

FIGURE 1 compiles some Gallup-style phrases similar to those in high-energy 12-bar Vincent classics like “Cruisin’,” “Race with the Devil,” “Blue Jean Bop,” “Jump Back, Honey, Jump Back” and “B-I-Bickey-Bi, Bo-Bo-Go.” Gallup typically kicked off a solo with an especially catchy idea, like the open-string triplet pull-offs in bars 1–3, and his phrasing generally emphasized chord tones or incorporated the chords themselves, as in bars 3–6. Like Les Paul, Gallup had a quirky, humorous imagination that he expressed with unusual textures, like the dissonant clusters in bars 7 and 8 and the precisely timed, chromatically ascending octaves in bars 9 and 10.

In the second chorus, the ascending arpeggio in bars 1 and 2 leads into a series of syncopated arpeggios in bars 3–8 that suggest Chet Atkins-style fingerpicking, minus an underlying bass pattern. Bars 9–12 include typical Gallup-style single-note runs. He never bent strings more than a half step and favored the sweet sound of the major sixth over the bluesier minor seventh, including the trademark 6–9 chord that caps off the solo.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Gallup’s wild energy and ability to handle fast tempos were second to none, but Vincent also recorded a number of sentimental ballads that required Gallup to solo over more sophisticated changes. Next month: rock and roll romance.