Hitting the Pocket: The Importance of Dynamics and Grooving When Soloing

Awareness of one’s rhythmic pacing is among the most important aspects of ensemble guitar playing.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Two of the most important and effective elements in creating expressive improvisations are the incorporation of dynamics and groove. Dynamics—the use of variations in volume and articulation that can span from quiet, delicate and gentle to loud, forceful and aggressive—and groove—the way in which a player chooses to place the notes against the backbeat—are both key aspects of musicality that come into play.

Awareness of one’s rhythmic pacing, or time, and the way in which it connects with a rhythm section is among the most important aspects of ensemble playing. It’s very beneficial to record yourself both when practicing and when playing with other musicians. When you listen back, you’ll be able to listen more objectively and hear if you’re playing in the pocket or if you’re rushing or slowing down, and this will serve to heighten your awareness to your groove overall.

Listening to great “time players” will also teach you just about all you need to know. Wes Montgomery was one of the most swinging guitar players ever, and so was Jimi Hendrix. Also, Eric Clapton is a great groove player and was especially so during his days with Cream. Many horn players, including sax great Sonny Rollins, have also had a big impact on my understanding of groove and dynamics. I also listened to a lot of Motown when I was a kid, music for which the groove was of the utmost importance. Once I started gigging a lot, I had the opportunity to listen to recordings of my own live performances and get a lot of helpful feedback from other people by asking them, “How did this groove feel to you?”

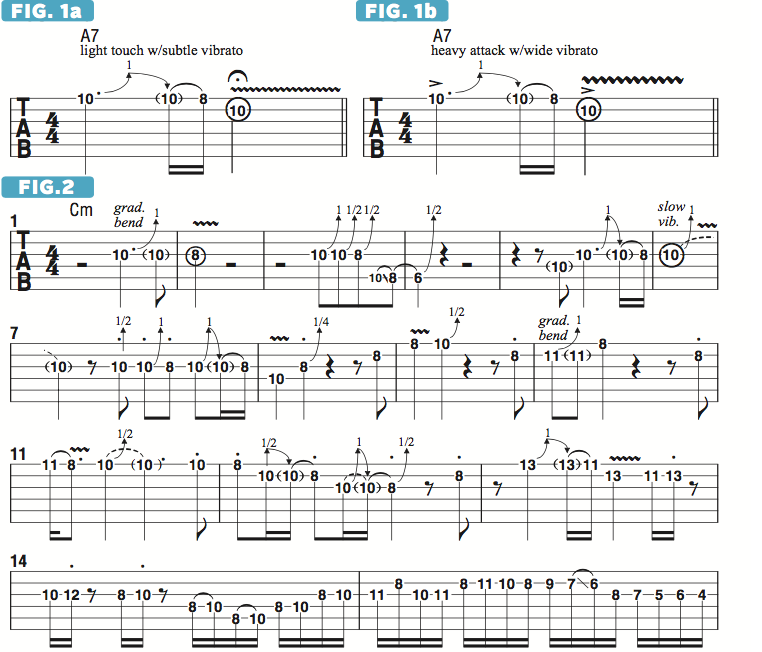

I believe that everyone knows instinctively how important dynamics are. For instance, I can radically change the musical feel of a phrase just by altering its dynamics. FIGURE 1a is a simple blues lick, played very softly and with a subtle vibrato. In FIGURE 1b, I play the same notes but turn up the guitar volume, use a heavy pick attack and a wide vibrato, and what I’m emoting on the guitar is completely different.

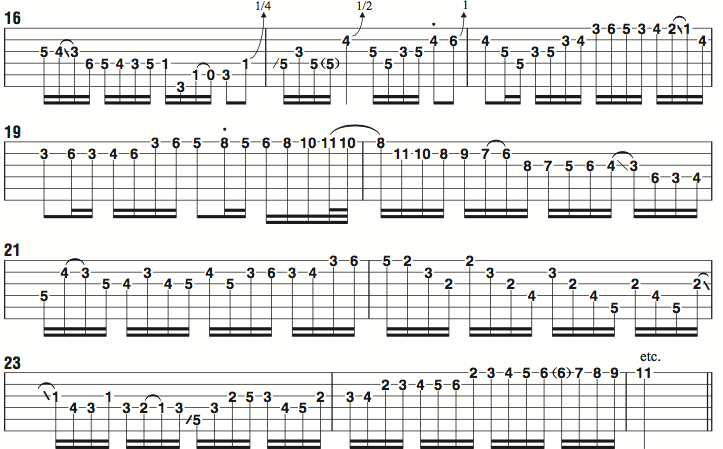

FIGURE 2 is a 24-bar improvisation over a static funk groove in C minor. In this example, I begin with soft, melodically simple blues phrases and gradually transition into lines that are more rhythmically and harmonically complex. For example, after 14 bars of leaning almost entirely on C minor pentatonic (C Eb F G Bb), I introduce at bar 15 the use of chromaticism to move down the fretboard. As you listen to this example, notice the ebb and flow of the groove, as well as the harmonic content of the lines. Try to incorporate some of these ideas into your own solos.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!