Warren Haynes Discusses His New Acoustic Folk Album, 'Ashes & Dust'

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Warren Haynes’ name is more likely to be evoked alongside those of Duane Allman, Jimi Hendrix, Eric Clapton, Paul Kossoff, Steve Marriott or even David Gilmour, rather than Bob Dylan or Woody Guthrie.

And yet there’s always been a literate storyteller’s heart beating within the powerful Gibson- and Marshall-fueled textures of his finest songwriting, going back to the emergence of his much-esteemed polymorphic group Gov’t Mule in 1995.

The Mule’s debut album nestled the anti-racism commentary “World of Difference” amidst its gloriously retro-leaning psychedelic excursions. And Haynes’ line of insightful carved-from-life telegraphy has continued though the lost-soul’s portrait “Wine and Blood” from 2004’s Deja Voodoo and through the song of rebellion “River’s Gonna Rise” from his second solo album, 2011’s Man in Motion, and through the self-examining “Spots of Time,” a tune Haynes wrote with the Grateful Dead’s Phil Lesh and played during the last years of his quarter-century stand with the Allman Brothers Band.

Haynes fully reveals his narrative abilities on the new solo set Ashes & Dust. The album teams the guitar potentate who’s also been part of the Dickey Betts Band and Phil Lesh & Friends, and shared the stage and recordings with Dave Matthews, the Derek Trucks Band and even William Shatner, with yet another set of collaborators: New Jersey based roots-music wranglers Railroad Earth.

“Having musical conversations without speaking about what to play is what I love,” Haynes declares. “That happened in a really organic way with Railroad Earth. I also love the fact that they all play multiple instruments, so we could talk about what might be good on a song-by-song basis and mix things up by varying instruments to tell the different stories on Ashes & Dust. We didn’t dwell on anything too much. We tried to capture as few takes as possible and grab the ones that felt the best.”

Despite the desperation ticking within tales like country songwriter Billy Edd Wheeler’s “Coal Tattoo” and Haynes’ own “New Year’s Eve,” Ashes & Dust has the vibe of a feel-good album thanks to the relaxed and intuitive performances that guide its mostly acoustic playbook. Haynes’ acoustic guitars and trusty D’Angelico New Yorker twine with the fiddle, banjo, mandolin, bouzouki, piano and resonator guitars in Railroad Earth’s front line to craft spider webs of angelic melodies on numbers like his new tunes “Is It Me Or You” and “Blue Maiden’s Tale,” and to propel Lesh’s Dead-like chord structure on “Spots of Time,” which makes its first recorded appearance.

The sound of Haynes and Railroad Earth—sweeping and swirling with rich, rooted influences—is perfect for these songs, which pluck images from the North Carolina mountains where Haynes grew up, the landscape of the Civil War, gospel tent revivals and urban wastelands to tell Ashes & Dust’s distinctly American tales. And true to the great storytellers Guthrie and Dylan, there’s even a streak of protest in songs like the satirical greed-head anthem “Beat Down the Dust” and the blight-ridden “Hallelujah Boulevard.” Haynes also pays tribute to a lost storyteller in “Wanderlust,” a 4:50 biography of country-rock innovator Graham Parsons.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

The album has an eclectic—naturally—guest list that includes Grace Potter duetting with Haynes on Fleetwood Mac’s “Gold Dust Woman,” vocalist Shawn Colvin and harmonica player Mickey Raphael on “Wanderlust,” and Allman Brothers’ bassist Otiel Burbridge and percussionist Marc Quinines on “Spots of Time.”

Although the Allmans folded their hand last fall, Haynes has kept up a juggernaut pace, directing most of his energy into Gov’t Mule. In the past year the Mule has teamed up for instrumental concerts and a live album with groove-jazz guitar hero John Scofield and released live recordings of the band covering Pink Floyd, Rolling Stones and classic reggae tunes. And the quartet continues to make every live show available for purchase on their Mule.net web site.

It’s a wonder Haynes had time to cut 30 songs with yet another group of collaborators. “But the truth is, I’ve been writing these more traditional songs all my life and I finally needed to create a home for them,” he says. “They didn’t necessarily fit the Allman Brothers or Gov’t Mule, or even my last solo record. They were looking for a little more acoustic and melodic treatment. And they just couldn’t wait any longer.” Haynes was taking a rare and well-deserved break at home when we spoke.

Ashes & Dust really celebrates storytelling, with vivid characters living in a vivid American landscape. What took you there?

The kind of imagery and almost talk-singing thing—like John Prine, Johnny Cash and Bob Dylan stuff from certain eras. When you heard those tunes, they took you on a journey. By the time the payoff came there was an excitement level that you couldn’t achieve in a regular love song, which is what most songs are. If you look at stuff I’ve written in Gov’t Mule, a lot of those songs come from that kind of folk influence. I’m also much happier being challenged as a songwriter.

That storytelling approach is not the easiest thing in the world to do unless you’re Dylan and can write “Hollis Brown” in eight minutes. To get a story to come to life in a reasonable amount of time is a challenge. Once a song like that is written, it’s up to the singer to keep the narrative interesting and the instruments are kind of ornaments, decorating the picture.

The acoustic settings of these songs also let me use my voice differently. Not having to sing over electric instruments lets me sing in a more warm and relaxed way. That helps to keep the stories in these songs intimate and real—like I’m just telling them to you, without any big production.

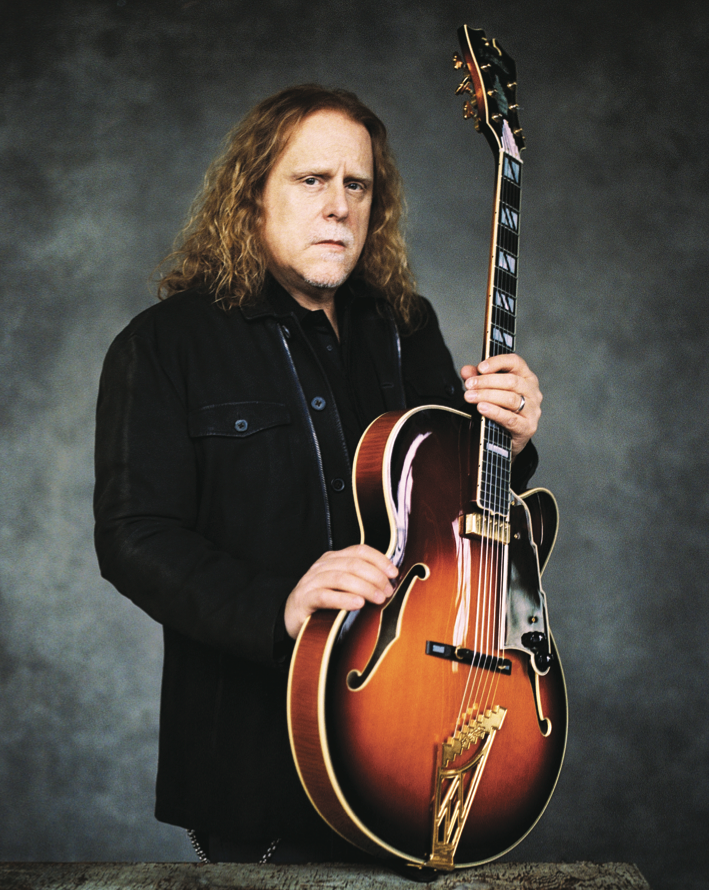

How did your D’Angelico New Yorker, a big box hollowbody you’re not often heard playing, become the star guitar of these recordings?

It has flat wound strings on it, so it’s not a guitar that I would want to play blues or rock solos on. But it’s really good for that vintage-y kind of Fifties/early Sixties sound when flat wounds were prevalent strings for a while. It makes me play a certain way.

When I’m not bending strings, for the most part, and playing in a jazzier or more melody-oriented way, the D’Angelico’s sound fits in with the acoustic instruments. So on “Coal Tattoo,” all that jazzy stuff at the end was tracked live with the D’Angelico, which is a reissue I’ve had for about 15 years. The slide is an overdub on one of my Les Pauls. Most of the songs have only one guitar lying in the tracks, but when there are two, chances are that’s the D’Angelico tracked live and the Les Paul added.

How does your acoustic guitar approach differ from your electric playing?

Mostly I’m trying to capture the vibe of the way the song was written. In some cases, I might start out playing it on acoustic guitar and realize I can get the same vibe on my D’Angelico or an ES-335, and feel like I can play a nice solo at the end of the song that takes it out of the acoustic realm. But playing acoustic guitar for me is much more tender, delicate. I’m more comfortable with an electric guitar in my hands, as far as performing is concerned. To be able to embrace the acoustic side and try to get better at it is a nice challenge.

The album’s acoustic aesthetic also makes the Celtic influence that’s been a vein in your electric guitar playing more prominent.

At the bottom of the traditional music from the mountains of North Carolina, Virginia, West Virginia and Kentucky is a thread of Celtic music. That’s part of what they call Appalachian music, brought over from the British Isles by the area’s settlers. I’ve had such a hybrid of influences.

My dad had a beautiful voice—still does—and he was listening to Bill Monroe, Ralph Stanley, Hank Williams and eventually George Jones and Merle Haggard. So I heard bluegrass and country early on, but not a lot more. And my two older brothers had every type of music under the sun. I was exposed to so many things that they all found their place in my music.

A lot of the big, explosive trademark sonic guitar palette we’re used to hearing on Gov’t Mule albums and your last solo album is absent here.

I used hardly any effects. The vintage Gibson Falcon amp I used on “Hallelujah Boulevard” and “Gold Dust Woman” has a weird tremolo in it that has some sort of sweeping modulation effect. It’s a very unique sounding tremolo. Other than that, we added a little slap-back or delay to some of the slide stuff. It’s a very organic sounding album.

How important is it for you to carry the American songwriting tradition forward?

It’s important to take the seeds your music grew from and plant them somewhere else. And I’ve always felt that it was especially important to take whatever tradition in roots music you grow up with and carry it forward in whatever ways you can. All the types of music I love are huge parts of music history and need to be carried on.

I also thought it was important that I acknowledge the Asheville area writers from previous generations that were influences and, in some ways, mentors to me. There were three in particular: Ray Sisk, Larry Rhodes and Billy Edd Wheeler, and I recorded songs by all of them for this album. Billy Edd’s the most famous of all the Asheville area songwriters. He wrote “Jackson” for Johnny Cash and has written songs for Neil Young, Jefferson Airplane, Richie Havens and Judy Collins.

I believe he just turned 82 and is in the Country Music Hall of Fame. He and I became friends when I was in my early twenties. We used to drive back and forth together from Asheville to Nashville. He had houses in both cities and we wrote some songs together. I was lucky to pick his brain a little bit. And Larry and Ray were local singer-songwriters that I would sneak into this folk club to hear when I was 14. We became friends and the next thing you know they’re teaching me about songwriting and we’re playing together.

Was there something they saw in you?

It was at least the gumption it took to sneak into a place I wasn’t supposed to be, called Caesar’s Parlor. This was a drinking establishment and could get pretty wild and decadent. Eventually word gets around, “Oh, this kid is a player. Let’s get him up onstage.” Simultaneously, I was studying blues, rock, jazz and other styles, but the singer-songwriter folk-influenced part of me was blooming.

Which artists that you listened to as a kid prepared you to hear the very adult songs—about dying coal miners and guilt-ridden bounty hunters—these Ashville writers were performing?

Dylan, who obviously changed everything, and I was starting to hear people like Jackson Browne and James Taylor, whose songs were a little more commercial but drew on a deep well. The local guys were writing songs that were on par with these artists, and since I had never heard any of it before, it was all affecting me equally. When I was a teenager the music scene in North Carolina, everywhere, really, was thriving and fertile.

It seems like the substance and depth that was present in a lot of pop music then—a time when Hendrix, Dylan and Neil Young were all played on mainstream radio—has dissipated today.

I agree.

There was an 18-year break between your first and second solo albums, so does delivering Ashes & Dust only four years after Man in Motion indicate you’ll be doing more frequent recording under your own name?

There will probably be one or two follow-ups to Ashes & Dust fairly soon, since we recorded somewhere around 30 songs. We toyed with the idea of releasing a double CD or two albums simultaneously, but this group of songs felt right together. And, of course, I’ve always got ideas for a few more albums in the wings.

How did Railroad Earth become your backing band for this music?

Six or seven years ago they opened up for the Allman Brothers at Red Rocks, and shortly after that I was booked to do a solo acoustic performance at DelFest [in Cumberland, Maryland] and they were on that bill as well, so I invited some of the guys to join me for a few numbers. It was pretty impromptu. We rehearsed a little in the dressing room and it went rather well.

Not too long after that I was going to do another solo acoustic performance at the Capitol Theatre in Port Chester, New York, and invited them again—this time with a little more rehearsal. It was really fun and beautiful and the chemistry was nice right from the very beginning. At that point I thought they’d be right for tackling this project.

We tried to record as live as possible. We were all set up in the studio so we could make eye contact and play like we were performing onstage. The majority of the music was captured that way. Even some of the vocals are live on the final tracks. We usually overdubbed the banjo—one reason being that banjo is so loud it tends to bleed into other microphones—and some of the slide guitar stuff was overdubbed.

You have such a varied career. What do you see as the glue that bonds all your work together?

It all stems from knowing that I would never be happy just pursuing one musical avenue. I write songs in a lot of different directions, probably because I listen to and love so many different types of music.

Somewhere along the line I realized that it's a luxury that some people aren’t afforded—to be able to pursue the different directions that they love—and I don’t take that for granted.

I think more music should be made in the way of people creating music that they love, and building a like-minded audience. I’ve never wanted to second-guess what people expect from me. I’m not sure if that’s great advice to give to a young artist, but it's worked for me so I consider myself fortunate.

AXOLOGY:

GUITARS: D’Angelico New Yorker, Gibson Warren Haynes Signature model Les Paul, Gibson ES-335 1959 Dot Neck reissue, Epiphone ES-335 style 12-string, Washburn Warren Haynes Signature model acoustic, Rockbridge Traditional Dreadnought acoustic, Seventies Guild acoustic

AMPS Gibson Falcon, 1965 Fender Super Reverb, Carr combo, Homestead combos

STRINGS: GHS Burnished Nickel Rockers (.10–.46), GHS Precision Flatwounds (.12–.50) on the D’Angelico New Yorker, GHS Vintage Bronze Acoustic (.10–.46)

SLIDES: Dunlop glass Moonshine slides, Coricidin slides