“Freddie was a good riffmeister! He was a devotee of Jimi Hendrix. People think he was just concerned with the lighter stuff but it’s not true. He did enjoy the heavy stuff”: Brian May reveals the inside stories behind 13 classic Queen tracks

In a world-exclusive interview, Brian May takes you behind the scenes of the making of 13 iconic Queen cuts, and reveals what inspired his magical guitar playing in Bohemian Rhapsody, Killer Queen, Don’t Stop Me Now and many more

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Brian May is feeling good. “A little tired,” he smiles, “but very happy.” On a cold winter afternoon, the legendary guitarist is talking to Total Guitar from his home in Surrey, a few days after the North American leg of Queen + Adam Lambert’s Rhapsody tour ended with another sold-out date at the BMO Stadium in Los Angeles.

“Everyone in the States has been saying that this show is the best we’ve ever done with Adam,” he says. “So it’s a great result. Wonderful!”

Certainly, the Rhapsody tour – which reaches Japan this month – is a huge production with spectacular state-of-the-art visual effects. “I’ve always loved to make a show a real event,” Brian says.

But it’s the music, of course, that continues to draw huge audiences for this tour across the globe – all of those great songs that Queen recorded with Freddie Mercury from the early ’70s until the singer’s death on November 24, 1991.

In a lengthy conversation with TG, Brian discusses the creation – and his role specifically – in many of the biggest hit songs and landmark tracks in Queen’s career. Ten of these songs featured in the setlist from that recent show in LA: Killer Queen, Bohemian Rhapsody, Love Of My Life, We Are The Champions, Don’t Stop Me Now, We Will Rock You, Another One Bites The Dust, Crazy Little Thing Called Love, Under Pressure and A Kind Of Magic.

One is a hit that Brian wrote with his tongue-in-cheek – the OTT movie theme Flash. Another has great poignancy as one of the last Queen songs released in Freddie Mercury’s lifetime – These Are The Days Of Our Lives.

And finally, there is a fan-favourite deep cut from 1980, Dragon Attack, picked out for TG by one of Brian’s greatest admirers, Metallica lead guitarist Kirk Hammett.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

As Kirk tells us: “I love Queen. I love all of it. I love all the stuff that everyone else loves. I especially love that song Dragon Attack.”

But before we get to that, we’re going all the way back to the 1970s, beginning with the hit single that defined Queen as one of the most inventive and original rock groups of that era…

Killer Queen

On the 1974 single that gave Queen their first taste of international success, Brian’s solo is exquisite – starting with some bluesy minor bends lower down the neck before the motif repeats higher up and swells into harmonised layers, adding depth in similar ways to the vocals in The Beatles’ early hit Please Please Me.

Similar usages of harmonisation can be found in 1961 track Pasadena by ’60s trad-jazz revivalists The Temperance Seven, and the cascading strings typified by Anglo-Italian conductor Annunzio Paolo Mantovani. As Brian has noted, it’s as if “the three voices of guitars are all doing little tunes of their own”.

Can you talk me through the process of writing and recording the guitar solo in Killer Queen?

“Well, I love the track. I think it’s one of Freddie’s most perfect creations. The story behind it is that I was in hospital. We’d come back from a tour in America and I got very sick with hepatitis, so when the other guys went into the studio to start making the Sheer Heart Attack album I was in hospital, with lots of complications. While I was there they brought a tape of Killer Queen in for me. They’d already laid down the piano, bass and drums, and they’d started putting some backing vocals on.

“I had loads of time to sit and think – to figure out where I wanted the solo to be and develop the idea in my mind. And what we ended up with is a solo that has lots of different parts. So it’s not just playing a verse, it’s being part of the arrangement and leading into a verse.

“I could kind of hear it in my head, and that’s always a good sign for me. I don’t like to go into the studio with no ideas. I like to have a clear idea of where I’m going. The main solo has three parts, three guitars. I could hear that solo in my head and I wanted to do this kind of bells thing…”

Bells?

“I call it bells. I don’t know what other people would call it, but it’s when you play a note on one instrument and then it carries on but the next note comes in from another instrument and makes a harmony with it while it’s still going. And then another one. It’s like a peal of bells where the sounds add up in sequence. And really I got it from listening to things like the Mantovani piece Charmaine [see above] in my childhood, where he does exactly that – a dissonant harmony.

“I know for a fact that The Beatles were influenced by that as well, because they did something similar in Please Please Me. It’s not quite the same thing, but it’s like adding instruments in to make the dissonance and the harmony.

We were influenced by The Beatles and Jimi Hendrix, where they actually painted pictures in stereo. And of course, we were able to start where The Beatles left off in a way, because we had much more up to date gear

“I should be talking about the Temperance Seven and a song called Pasadena. The three lead instruments, which I think is a trumpet, clarinet and trombone, they do this bells thing. And I was always inspired by it. I always wanted to do it, and that was the opportunity.

“In the third section of that solo, that chiming bells effect is enhanced with stereo panning. So if you’re listening, particularly in headphones, you get that feeling of things happening in stereo.

“Yeah, we were always into stereo. We were influenced by The Beatles and Jimi Hendrix, where they actually painted pictures in stereo. And of course, we were able to start where The Beatles left off in a way, because we had much more up to date gear, and we had a lot more tracks to play with. So we went with those influences, but we were able to take things a lot further.”

Bohemian Rhapsody

Freddie Mercury’s masterpiece is a six-minute suite of world-conquering brilliance. And in its climactic hard rock section, the riff, written by Mercury on piano, feels quite unnatural when transposed onto guitar.

It starts on the sixth fret of the A-string and climbs back up from the third fret of the low E in a way that implies G Phrygian, the third mode of Eb major. Towards the end of the idea, the original opening note moves up a tone and the same shape repeats, the A note on the sixth string suggesting a key change into A Phrygian, the third mode of F major.

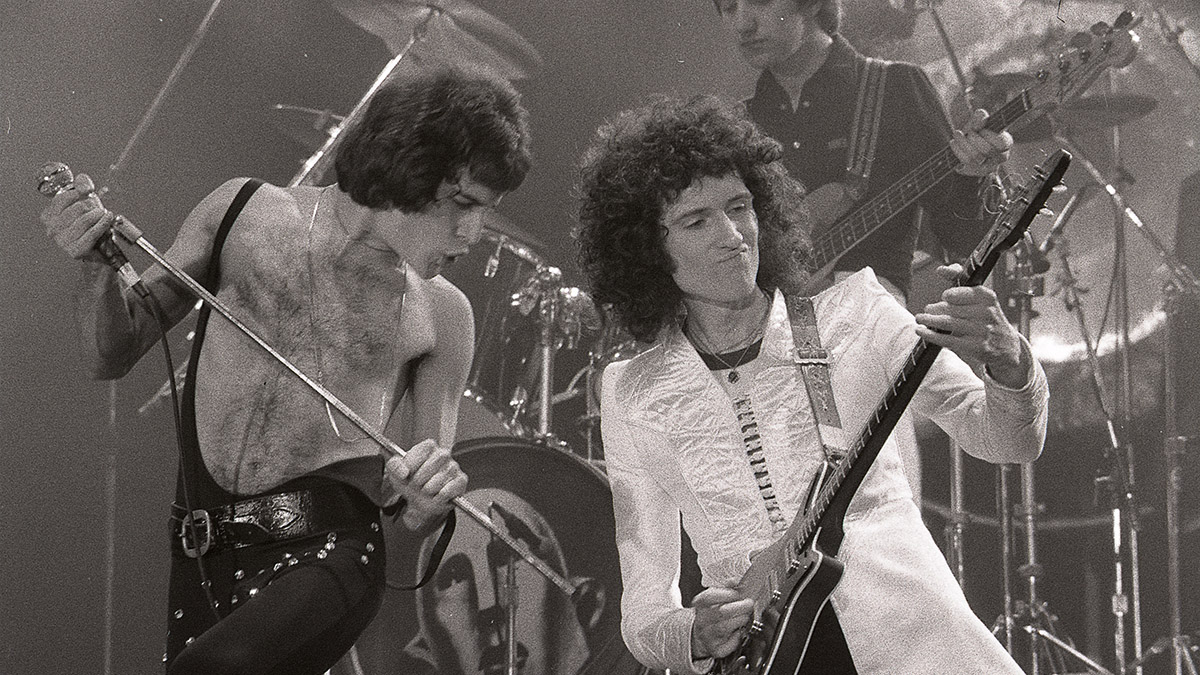

Freddie was a good riffmeister, really! That riff for Ogre Battle, a lot of people think that’s mine, but that came out of Freddie’s head

In previous interviews with Total Guitar you’ve spoken about the guitar solo in Bohemian Rhapsody, but let’s talk now about that song’s end section, in which the band really rocks out. It was Freddie’s song, so did he have all of it planned out, or was that rock section worked out with you?

“It was more Freddie’s idea. Freddie had that riff in his head and he played it on the piano, which is quite difficult because he plays in octaves. I just worked off that and slightly adapted it to the way a guitar needs to play it.

“And I was able to do a lot of interesting stuff with sounds because in Bohemian Rhapsody, I pretty much use every sound that my guitar can create with different pickup combinations. So even during the course of those riffs, the sound is changing because there are different guitars coming in with different pickups selections.

“But it’s funny – Freddie was a good riffmeister, really! That riff for Ogre Battle [from 1974’s Queen II], a lot of people think that’s mine, but that came out of Freddie’s head. So he had very good ‘heavy’ sensibilities. He was a devotee of Jimi Hendrix. People think he was just concerned with the lighter stuff but it’s not true. He did enjoy the heavy stuff, too.”

The Bohemian Rhapsody riff in particular doesn’t sound very guitaristic in an obvious sense…

“No. It’s not a riff that a guitarist would naturally play. And that’s a double-edged sword. It’s difficult for the guitar to get a hold of it, but once you have got hold of it, it’s very unusual. And to be honest, I still don’t find it easy!

“I can play it at home okay, but in the heat of the battle, if you like, when we’re playing it live, and there’s huge adrenaline, it’s the climax of the show and that riff comes along, it’s not the easiest thing to play.

“I’m excited and I’ve got to keep the passion, but I’ve got to keep a part of my brain cool just to handle where the fingers have to go because it isn’t natural. It’s one of the most unnatural riffs to play you could possibly imagine. But that’s that is the joy of it, really, because it’s so unusual.”

Yeah, I have learned it myself in the past…

“It involves a lot of stretching of the fingers, doesn’t it?”

It does, and it’s definitely very complex. I probably should have guessed that it was a Freddie thing because it’s just so un-guitar-y in that respect.

“Yeah, well, Freddie had a habit of writing an Eb and Ab, and so it was always a challenge for me to find places on the guitar to make that work. But it obviously contributed a lot to the way I developed as a player. It was a good thing, even if it was… strange!”

Love Of My Life

The original recording of Mercury’s beautiful ballad on the 1975 album A Night At The Opera features May on harp and, of course, his Red Special, which was used for the sustaining string-like notes that are introduced halfway in, as well as the harmonised leads in F major that arrive shortly after.

Later, a different version was rearranged for 12-string acoustic and transposed minor 3rd down. This version featured on 1979’s Live Killers, and due to the song’s popularity with South American audiences it was released as a single and became a huge hit in Argentina and Brazil.

How did you go about turning this song from a piano arrangement to the acoustic guitar arrangement that you perform live?

“That happened very quickly with just me and Freddie. It was obvious that we couldn’t do the arrangement on the record because it’s so complex. It’s not just the piano, it’s got harp and all sorts of lovely backing. And it’s got a whole orchestra of guitar. So we couldn’t do it live that way. I don’t know whose idea it was, but Freddie and I thought we would just try and do it as the two of us with an acoustic guitar.

“So I just started playing it. I think it’s even in a different key. I played it the way it was easy to play on an acoustic and it was just thrown together in a few minutes, to be honest. The song became so enormously successful in South America that we eventually put it out as a single in that style. But you can tell it’s enormously simplified from the way it is on the record.”

The guitar part is quite sophisticated. It doesn’t feel like a simple strummed three- or five-chord vamp, as it were.

“No, you’re right. It’s not strummed, it’s picked. And I suppose I was trying, in my mind, to do what the piano did on the record – in my own way. And it grew. It gradually grew into something which stood up on its own. And that guitar solo in the middle, I don’t even know where that came from, to be honest. It just kind of grew out of the atmosphere of doing that thing live.”

We Are The Champions

Two of Queen’s greatest songs are inextricably linked – May’s We Will Rock You and Mercury’s We Are The Champions, released as a double A-side single in 1977, and often paired for live performances. Brian’s guitar work in We Are The Champions has more of an overdub feel – especially as there’s no dedicated solo section.

Instead, May duels against Mercury’s vocals basing himself around the first position of D minor pentatonic at the 10th fret in order to imply F major. It’s one of the oldest tricks in the book for playing in major keys – shifting down three frets and playing the relative minor shape instead.

There’s plenty of guitar playing in this song. But was a breakout solo ever considered or discussed? A melodic break-type solo? Do you think it could have worked?

“No, it was never discussed. But what was discussed was that Freddie wanted the guitar to be fighting with the voice towards the end. It’s a strange story. I’d done the rhythm part for that, and sort of forgotten about it. And then I think we were in Wessex studios. And it came quite quickly to the time when we were going to mix it, and I suddenly thought, I haven’t really thought about this, there’s not really any lead guitar on there.

“And I came back into the studio on the morning of the mix, and basically redid most of it, because I could hear it much more clearly in my head. And I put in those answering pieces, the lead guitar responses to Freddie’s vocal, particularly at the end. Also, again, those little bell chimes-type things in the second verse, because I’d sketched it but it wasn’t clear.

Freddie said, ‘No, I want to handle the guitar. I want to push that guitar to make sure it fights with the vocal’

“So I redid all that. And Freddie came back in and said, ‘Oh, I like what you’ve done with the guitar at the end. I want to make sure we mix it so the guitar is fighting with the vocal at every point at the end. It should be a battle!’

“And Freddie, when we were mixing it, had his hand on the guitar fader. Now, this is unusual, because usually he’s got his fingers on the vocal and I’ve got my fingers on the guitar. But he said, ‘No, I want to handle the guitar. I want to push that guitar to make sure it fights with the vocal.’ So that’s the way it was done.

“So that song doesn’t have a solo as such, and I don’t think it’s ever needed one. And the problem would be live. Once you started soloing extensively, the bottom would drop out of it. And I can do a lot with bluff on the night. I can make people think there’s still a rhythm guitar there. But not for very long…”

Don’t Stop Me Now

It is not a particularly guitar-driven song – but that all changes two-thirds of the way in, during the solo section. As with We Are The Champions, the song is in the key of F major, but the leads are performed three frets down using its relative minor D.

As for the warm but ever-so-slightly quacky tone, it’s most likely May was using his neck and middle pickups together with both set in phase – the Red Special with independent on/off sliders for each pickup, doubled by phase selectors underneath, giving him 27 different combinations in total, as well as more control via the volume and tone knobs.

Can you tell us how this song’s solo came together?

Freddie saw it very much as a piano song, a la Elton John, really. Powerhouse piano, powerhouse vocal, and that’s it

“Yes, it’s quite funny. Freddie saw it very much as a piano song, a la Elton John, really. Powerhouse piano, powerhouse vocal, and that’s it. So I played lots of rhythm guitar on it, and Freddie still said, ‘No, no, no, no – it’s a piano song!’ That was a bit disappointing, but he did say, ‘Well, it does need a solo. I need you to take over the vocal.’

“Which is what the way we thought about things. I said, ‘Okay, give me a verse and let me see what I can do.’ And again, being in the studio and hearing it evolve, I could sort of hear the solo in my head before I actually picked up the guitar to do it. As very often with me, it’s a kind of little diversion. It’s a counter melody.

“It’s not the actual tune of the verse. But it’s something which goes with it, a sort of counterpoint, and it’s something I could sing. And it was just a question of transferring it to a guitar. It’s very simple. And I sometimes feel a bit apologetic about it. But I do notice that when it’s played in the dancehall, it gets a reaction from people in the solo and it steps up the energy quite a bit, even from a song that’s got high energy, so I’m happy with it the way it is.”

It must be one of Queen’s most popular songs.

“It is now. It wasn’t in the beginning. It was a sleeper and it grew. And worldwide now, it’s a massive Queen song.”

It’s certainly one of those solos that takes the song to a whole new place, but why do you feel, as you say, apologetic for it?

“Well, it’s a little too typical, perhaps? Maybe that’s why I feel kind of apologetic. But the funny thing is, I’ve had years and years to live with it, and every time the solo comes up live, I think, well, actually I can’t do much better than that! So I tend to play it more or less as it is on the record – with little variations. But it just works as a as a counter melody for the for the main melody.”

As a listener, it does seem like the ear draws you in to that melody. You kind of want to hear it once you know the song.

“That’s what I feel. I feel like the audience is singing along to it, and it would be disappointing to them if I didn’t play it!”

We Will Rock You

In its original form, Brian’s monumental anthem is arguably Queen at their most minimalistic – with no melodic information to accompany the vocals until its final 30 seconds.

First the guitarist rings out some feedback (an E note, to be precise) and then strikes a C powerchord before introducing some ideas in open position A that recur an octave up around the 14th fret. May then juxtaposes an D/A shape against the straight major chord, adding melodies using the higher strings – almost as if he’s playing rhythm and lead at the same time.

The faster, guitar-driven version which opens 1979’s Live Killers omits this outro section and reimagines the song in E minor.

![1. We Will Rock You (fast version) - Queen Live in Montreal 1981 [1080p HD Blu-Ray Mux] - YouTube](https://img.youtube.com/vi/LGBUJL5uS_c/maxresdefault.jpg)

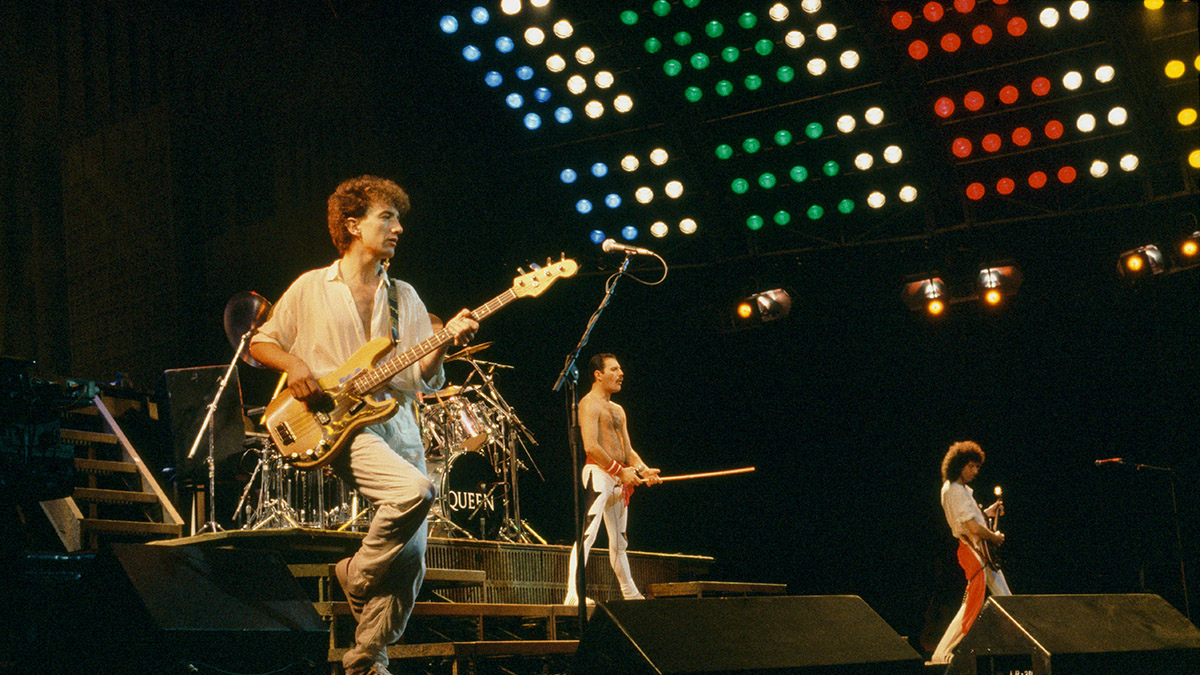

I’d like to talk about the live version of We Will Rock You that features on the Live Killers album as the opening track. It’s fast and furious and almost punky in its attack.

“That came about because of trying to visualise the openings and closings of a Queen show. That’s always something I’ve been very involved in. It’s one of the areas that inspires me. I like to create an event. And, of course, you play a lot of songs during the course of an evening, but the opening of the show is an event, and the closing of the show is also something that’s going to stick in people’s mind. So it’s always fascinated me, I’ve always been drawn to it.

“So, [the fast version] came about from thinking about how we could start the show. At this point, We Will Rock You already featured at the end of the show, but I thought, what would the audience be like if we started the show with We Will Rock You? And if we start the show with We Will Rock You, how do we go about it? Basically, they want to rock; they want to just rock out at that point. And so I could hear in my head a fast version of We Will Rock You – a sort of all-out punky-type version, as you say. And it happened very quickly.

Dave Grohl is very fond of it, so we did that with him at the Taylor Hawkins tribute show. It’s just an easy thing to play

“We just tried it out and it worked in rehearsal, and that became the opening of the show for that period. It worked out great. Much later, we did an adaptation of it for the We Will Rock You musical; that’s what plays when the actors come forward and take their bows, and it worked out very well. And from time to time we just fancy playing it fast. And sometimes we have other people that fancy playing it.

“Dave Grohl is very fond of it, so we did that with him at the Taylor Hawkins tribute show. It’s just an easy thing to play. It’s got a lot of slog in it. It’s got a lot of energy and power. And not too much thought! And it’s something which is… just, there. And it’s always a nice place to go.”

Another One Bites The Dust

Bassist John Deacon – affectionately referred to as Deacy – wrote a handful of the band’s biggest hits, including this Chic-influenced track from Queen’s 1980 album The Game.

What’s more, it was Deacon who played the funk rhythm guitar on this track, with Brian contributing rock licks. For the rhythm guitar parts, Deacon played an E minor chord rooted on the seventh fret of the fifth string, an A minor rooted on the seventh fret of the fourth string and another variant of same the chord in fifth position, sliding up from a fret down at the end of the phrase.

Am I right in thinking that this song is influenced by Chic and Nile Rodgers?

“Yeah, this track is very much John Deacon world. That’s what he was into. He was much more into funk than we were, and he brought that into our workings. It’s very Deacy and it’s very much influenced by Nile Rodgers.”

So as a Deacy song, how influential was he in the whole arrangement? How much did he tell you what to play in this song?

“Well, I don’t think I was in it at all to start off with! Because he’s hell bent on getting what he wants. So it’s his rhythm guitar playing – it’s not mine. That very funky style, that’s John. Oh yeah. And he wanted Roger to have a sort of disco-type sound. And it’s all done on a loop, so Roger reluctantly put loads of tape on his drums and played very stiff, and Deacy made a loop out of it. So it starts to be unnatural at that point. It’s a damn good loop, though, and it’s beautiful. And Deacy did the bass, Deacy did the rhythm.

“He worked with Freddie on the vocal. Deacy didn’t sing, so he would tell Freddie what the words were, and play the tune on the guitar. You can imagine it was quite a strange process. Freddie absolutely adored it. He just stepped into it with a vengeance. And he sang it until he bled! He was forcing himself to get those high notes and he loved it. Freddie really was such a driving force.”

“Because, to be honest, it wasn’t going down very well with the rest of us. You know, Roger actually didn’t want to have it on the album, didn’t like it. It was much too funky and not enough rock for him. I was a bit on the fence. I kind of enjoyed it. But it obviously wasn’t the rock that I would have been creating. And I remember saying, ‘Look, it needs a little bit of something a bit more dirty on it.’

“So I started playing these little bits of the more grungy guitar. I don’t think the word ‘grungy’ existed in those days. But the distorted guitar is obviously me, and that punctuates it and gives it another dimension, takes it to a slightly more rocky place.

“I remember Michael Jackson hearing it and saying, ‘That’s where I want to be. That’s what I want to do.’ And I think his whole album which followed [Thriller] was deeply influenced by Another One Bites The Dust and the fact that it straddled funk and rock. Michael came to the same place from a different direction. Very interesting!”

Do you remember what guitar John played? Did he play your guitar?

“Not my guitar, no. It was a Strat, I think. I’m pretty sure of that.”

It’s funny – it doesn’t sound quintessentially Strat-y.

“I suppose it doesn’t. Well, you can ask him – if you can get hold of him! You know, my memory is telling me it was a brand new Strat. At least that’s the way I remember it. I think I can remember him playing it. It’s not my style.

“And when we do it live, that’s one of the more difficult things I have to do. And I have to not try too hard, because it has to roll off the wrist in a very natural way. And you have to get the sound exactly right. It can’t be too burned out or it doesn’t work. It can’t be too turned down or that doesn’t work either. It’s tricky to get that sort of real clean funky sound. It comes and goes with me. Sometimes I just do it my way.

Another One Bites The Dust is a very important part of the Queen canon. It’s perhaps our biggest song ever in terms of sales. I’m not sure, but it must be close

“Sometimes I veer back more to the way of John’s playing. I always think about John when I’m playing it – always. I can’t be John, you know, nobody can be someone else. So I do it my way. And I can edge it up into being a little bit more dirty in some of the some of the parts where I’m playing with Adam. I enjoy doing it with Adam, he brings something different to it.

“And the song, it’s actually still evolving, which is quite something after all these years. So every time we do it, it gets a little bit of a different drift. And I enjoy it a lot more these days. Because we have made it our own I suppose. It’s quite heavy. And we do it early in the set at the moment, which is quite adventurous. It’s in the sort of rock part of the set, which in the beginning you never would have thought.

“That song is a very important part of the Queen canon. It’s perhaps our biggest song ever in terms of sales. I’m not sure, but it must be close.”

Crazy Little Thing Called Love

Written by Mercury in 10 minutes while he was lounging in a bath at the Bayerischer Hof Hotel in Munich, Crazy Little Thing Called Love was a tribute-of-sorts to early rockers Elvis Presley and Cliff Richard.

By the singer’s own admission, the restriction that came from his limited knowledge of the fretboard and chord shapes is what helped him write “a good song, I think”. Brian complimented its lazy D Mixolydian feel with ad-libs inspired by Elvis Presley’s guitarist James Burton. It’s a rare example of him recording an electric that wasn’t his Red Special, and there is more of a twang to his lines than usual.

Famously, you didn’t use the Red Special on this song. What guitar did you use?

“It’s Roger’s. And I think it’s actually a [Fender] Broadcaster. I think it was one of those early sort of [Telecaster] prototypes, which they called a Broadcaster. I could be wrong, because Roger had a lot of those very rare guitars, and he just happened to have this one in the studio. I was actually going to do it on my guitar, because maybe if I set it to just the bridge pickup it sounds a lot like a Telecaster.

“I remember saying to Mack, our producer, ‘I want to make this sound like James Burton. This is a pastiche of rock ’n’ roll. James Burton is my hero. This is a James Burton solo and it should sound like a Telecaster.’ And Mack looked at me quizzically and said, ‘Well, if you want it to sound like a Telecaster, why don’t you play a Telecaster?’ I thought, ‘Okay!’, and Roger just happened to have this other guitar, so I picked it up, and it yes, it had the right sound, obviously. The perfect sound.

“And I think I did it through a Fender amp rather than my usual Voxes. So, yeah, that’s the sound, and it worked out great.”

Flash

Unlike anything Queen had recorded before, there’s a prog rock intensity to this May-penned theme for 1980 space adventure movie Flash Gordon. The piece features vocals from both Mercury and May, with drummer Roger Taylor providing the higher harmonies.

As well as the usual fretwork on his Red Special, Brian was also responsible for all the piano work (an Imperial Bösendorfer Grand Piano with 97 keys instead of 88) and synths (performed on the Oberheim OB-X that he plays in the music video) – all of which layer together and combine into a retro-futuristic symphony that perfectly encapsulates the daredevil sci-fi spirit of the movie.

Flash is an interesting song. It almost sounds like a Freddie song, because it’s so flamboyant. Was there a brief for this? Take us through the writing process…

Having seen the rushes of the film, we had a session with Dino and Mike Hodges, all of us in Trident studios playing back what we done for the film. And Dino sat there with a face like iron

“I was so immersed in the Flash Gordon project. I always loved that kind of ’50s science fiction stuff anyway, and I was very aware that the way that the film was evolving was very comic book. It was very tongue in cheek. Very retro. Mike Hodges, the director, handled it that way in a very clever approach, I think.

“Strangely enough, Mike didn’t see eye to eye with the producer of the film, Dino De Laurentiis, who was the guiding force behind the whole thing. Dino saw it more as a serious epic, but it was Mike who said, ‘No, you can’t do that. It’s got to have this element of fun and slightly taking the mickey out of itself.’

“In the end, Mike won, and some of what I was trying to do with this track is to do a comic book in sound. That’s exactly what it is. And it’s slightly exaggerated. It’s sort of little over-heroic, if you like. But it’s fun and it’s colourful.

“But there is also a little undercurrent of something deeper in the lyrics: ‘Just a man/With a man’s courage.’ That, to me, is what gives it its heart and soul, because there is something rather lovable about the character of Flash Gordon. He’s so innocent. And there’s this love affair going through the film as well, and I think you really warm to him as a character, even though he’s unreal, he’s a comic book character.

“So that’s what I tried to put in the song. And I wanted to make it something that people would just grab ahold of very easily, and I could hear [the vocal shout] ‘Flash!’ very quickly in my head. So it was just a question of realising it in the studio. I had a lot of fun with it.”

And when you had the song finished, did Dino De Laurentiis like it?

“Well, when we’d made all the tracks in demo form, having seen the rushes of the film, we had a session with Dino and Mike Hodges, all of us in Trident studios playing back what we done for the film. And Dino sat there with a face like iron. Like, ‘I’m not sure if I like this?’ And the last thing we played was Flash and he went, ‘Yes, it’s very good, but it’s not for my film.’

“That was a mortal blow for me. I thought, ‘I didn’t encapsulate what the film needed.’ But Mike took me aside and said, ‘Don’t worry, I’ll sort him out. He will love it!’ And the conclusion of the story is when we had the premiere of the film. Dino came over to me and said, ‘Thank you for what you did for my film. It’s beautiful!’ So that was nice.”

It perfectly encapsulates the vibe of the film.

“Yeah, I’m very proud of it. It is very fluffy, but I’m proud of it because within my brief, within the genre, I think it does fit perfectly.”

Under Pressure

Two of the biggest acts in rock music collaborated to produce a worldwide smash hit, giving Queen their second number one single and David Bowie his third.

Under Pressure came from an impromptu jam at the Queen-owned Mountain facility in Montreux. The verses have May ringing out his open D against notes on the higher strings, followed by thicker-sounding open G and A7 shapes and overdriven chords from halfway in.

The main bassline was sampled by Vanilla Ice for 1990 hit Ice Ice Baby – the first hip-hop single to top the US chart – although Queen and Bowie were not credited until after its success.

I remember saying to David, ‘Oh, it sounds like The Who, doesn’t it?’ He says, ‘Yeah, well it’s not going to sound like The Who by the time I’ve finished with it!’

It’s an unusual song in Queen’s canon. Obviously, David Bowie featured, and it feels very much composed around the two vocalists. So how did you feel your part was played in that? What did you contribute to the song?

“Well, it was a very complex process. And of course, it’s the four of us plus David Bowie, who is a very persuasive force. And it was put together completely off the cuff. And David brought this technique in where everyone would go in and sing the way they felt the song should go without thinking about it. And without listening to each other. And then there was a whole system of going through and picking out the bits that you liked from different people’s vocals. So that’s how the vocals were put together.

“And David, in the end, wanted to be the guiding force as regards lyrics, and he ended up writing all those lyrics, with not much from us. And it was all done spontaneously in the studio very late at night after we had a meal and a lot of drinks. And it was a pretty heavy backing track.

“When it gets to ‘Why can’t we give love’, we were all working on it together, and it sounded like The Who. It sounded massively chord-driven. And I was beaming because I liked The Who. I remember saying to David, ‘Oh, it sounds like The Who, doesn’t it?’ He says, ‘Yeah, well it’s not going to sound like The Who by the time I’ve finished with it!’ You know, in a joking kind of way. But he didn’t want it to be that way.”

“It was very difficult to mix because we all had different ideas of how it should be mixed. I think it’s probably the only time in my career I bowed out, because I knew it was going to be a fight. So basically it was Freddie and David fighting it out in the studio with the mix.

“And what happened in the mix was that most of that heavy guitar was lost. And even the main riff, I played that electric, pretty much in the sort of arpeggiated style which I do live now. But that never made it into the mix. What they used was the acoustic bits which were done first as a sort of demo.

I never liked it, to be honest, the way it was mixed. But I do recognise that it works. It’s a point of view, and it’s done very well. And people love it. So we play it quite a bit different live, as you probably noticed, it is a lot heavier and I think it benefits from it. I mean, David was an awesome creative force. But you can’t have too many awesome creative forces in the same room. It starts to get very difficult! Something has to give.”

You might say that in some respects it doesn’t even sound all that much like a Queen song. You know, as you say, in the sound of the overall mix.

“Yeah, if I’d mixed it, it would have sounded very different. And maybe it wouldn’t have been a hit. Who knows?”

It’s surprising to hear you say that it was so improvised.

“Oh, completely improvised! There was no prior writing whatsoever. The only thing we had was the bass riff. We started off before dinner, and John had this nice bass riff, and when we came back there was a dispute.

“We said, ‘Let’s try and build on that nice bass riff.’ But no one could remember how it had gone – least of all Deacy, who’d had more to drink that most of us! So there was a lot of discussion, and I remember David stepping in at one point and saying, ‘No, no, it wasn’t like that – it was like this!’ And so to this day, I don’t know if that riff the same one that we had before dinner, but it’s the one that ended up on the record!”

A Kind Of Magic

The third single from the album of the same name was penned by Roger Taylor for 1986 fantasy action film Highlander, with many references to the film in its lyrics.

Its standout guitar parts include the same kind of chord motif heard in We Will Rock You, once again played around the 14th fret, and the faster licks in A Mixolydian and A major heard near the end of the song.

A Kind Of Magic was the album that followed Queen’s legendary show-stealing performance at Live Aid in 1985, and it was the sound of a band full of confidence and creativity.

A Kind Of Magic is quite a shreddy song with some really fast licks towards the end. Can you give some tips as to how you’d approach playing them?

“I don’t usually play them these days! I just like to go off and do my own thing, really. It’s an opportunity to have some fun with it. And if I was actually going to play those licks, it would be like being in a straitjacket because they’re difficult to play and I would be worried about my fingers being in the right place – and I don’t enjoy that!

The video has the guitar with fireworks coming out of the top of it, and I always thought would it be great to do that live. Well, we could do that now! Yes, it is childish, but it gives me such a lot of pleasure

“I’d much prefer to just do what comes into my head. And that’s one of the places in the show these days where I have no idea what I’m going to play when I get to that solo. And I like it to be that way, so it can go anywhere.

“I also have an extra weapon, which is the rocket I use. You know, we fire rockets during this song. I fire the rocket. It’s a childish toy, but it means that I can fire rockets in the air exactly the way I always dreamed of doing it when we made the video for that song.”

“The video has the guitar with fireworks coming out of the top of it, and I always thought would it be great to do that live. Well, we could do that now! Yes, it is childish, but it gives me such a lot of pleasure. And I can do it whenever I want. It’s a surprise for the audience. And the solo builds itself around that.

“So, those are the little peaks where the rockets come out. And I kind of fill in the gaps and try to lead the audience towards wondering what’s going to happen next. I have a lot of fun with it really.

With a Queen show I like to create an event. That’s always something I’ve been very involved in. It’s one of the areas that inspires me

“To me, it’s a lot better than kind of showing off and doing the fast stuff. There is a little bit of fast stuff still in it, but it’s basically playing with the audience. That’s what I like to do at that point.”

So do you have some special modification to one of your guitars?

“Yes, there’s one particular guitar which has it all built into it – or built on to it, I should say. It’s a lot of fun, and the audience love it. Sometimes the simple tricks are the best. Like the mirrorball. Everybody loves a mirrorball. Which we use in the solo for I Want To Break Free. It gets a huge round of applause, and they’re not applauding me – they’re applauding the mirrorball!”

These Are The Days Of Our Lives

In this beautiful synth-driven ballad, written by Roger Taylor, the lyrics reflected on the band’s shared experiences early on and the love that brought them together. The video was filmed in black and white, with a frail-looking Freddie Mercury at the very final stages of his life.

Although the use of rhythm guitar in this track is fairly sparse, there are some incredibly melancholic lead lines from May halfway in – starting in A natural minor and then phrases in D minor which repeat a whole tone up in E minor – and more passages wrapped around Mercury’s vocals towards the end.

Let’s talk about the solo in there. I love the tone, the delay effects…

“Well, it’s a very delicate song and I was aware it had to be a very delicate solo. I started experimenting with the delays live, so it’s not like we put an effect on the solo afterwards – I was playing using those effects to make little harmonies, as I’ve fairly frequently done, but this was a very different atmosphere from anything we’ve ever done before.

It’s a very delicate song and I was aware it had to be a very delicate solo

“And those little arpeggiated runs, I did very quickly as an experiment. But as soon as I’d done it, I liked it. That’s the second part of the solo that I’m talking about. I remember sitting with Freddie and him going, ‘Oh, yeah. That’s nice. You know, when you get that together it’ll be quite good!’ And I thought, I actually don’t want to change it. I said to him, ‘I quite like it the way it is.’ And he came around, eventually; he liked it too.

“Of course, it’s Roger’s track, so Roger is going to have the ultimate say as to whether it goes on or not, and he liked it so that’s the way we kept it. And that guitar is woven into the whole song. It’s not just in the solo. It does little duets with a vocal all the way through. It’s quite delicately woven, that song, and I love it. I think it’s probably Roger’s best song ever. It’s a beautiful song.”

Are you mixing up picking and fingerpicking in this song?

“It’s not fingerpicking, actually. It’s just very delicately played with a pick, mainly. I wasn’t so much into using my fingers in those days. But the solo is; oh, yes, you’re right. I am doing it with the soft part of my fingers. I beg your pardon. You’re right. I’d forgotten!”

Dragon Attack

This powerful deep cut from 1980 album The Game is another example of Queen taking influence from the funk sounds that were popular at the time. But it’s more rock than disco – sounding almost like the kind of riff Thin Lizzy would have come up with in the mid-to-late ’70s, in this case built around the D minor pentatonic scale.

Breaking down the solo in his 1983 Starlicks instructional video, Brian explained how “with that particular screaming tone setting and also by hitting the string with your pick and the thumb, you can get those octave harmonics coming out, which gives it a bit more tension and screams a little more.”

Kirk Hammett tells us that Dragon Attack is his favourite Queen song. I’d love to get your reflections on it…

“Well, I love it too! It’s got such an amazing feel. We were in that funk place, but this one has a real kind of rock-funk feel. And again, it started off very spontaneously, me playing along with Deacy. And, probably, it was more Deacy’s riff than mine, to be honest. But I took hold of it and built it into the song that it became.

“It came out of spontaneity, and it came out of, I think, wanting to play the kind of music which was inspiring us when we would go down to the rock disco after work in Munich every night.”

“We used to go to a place called the Sugar Shack, and it was definitely a sort of rock club, a rock dance club, if you like. And generally they would play Queen music, but when Queen music came on it didn’t work so well, it didn’t inspire people to get up and go nuts on the dancefloor, whereas a lot of other things did – songs that had a lot more space in them.

“So what I tried to do with Dragon Attack was make it the kind of track which was going to work in the Sugar Shack. That’s totally what it was about, which was to get girls excited and make boys want to get up and go nuts with them on the dance floor there. So it’s very spacious.

“The song doesn’t have the usual kind of rhythm build-up. It’s just the riff – bass, drums, guitar. Very open, very stark. And the lyric also comes from the Sugar Shack, if you want to know what that’s about?”

Who wouldn’t?

“The dragons are in the sugar shack. It’s about that strange twilight world where you stay till the lights come on in the morning, and you come out and it’s dawn! It was a pretty wild time for us, and that’s what I attempted to put in the song. It’s all about us and the way things were, and the sort of sexy side of the peripherals of rock. That track was designed to be uniquely a dance track. So you have Another One Bites The Dust and Dragon Attack which are both big departures from the way Queen had come up.

“I remember touring after we finished the record, and American radio picked up on those songs just like that. We never expected they would. We thought they would want just the rock tracks. But they picked up on that stuff and it was all over! Every time we got into a limo or car or a restaurant or whatever, they wouldn’t be playing those tracks.

It gave birth to Michael Jackson doing his incredible stuff – and later, Michael Jackson inviting Slash to play on a track with him

“And it’s interesting – it was the same time as The Rolling Stones put out Miss You, which is also very funky; very different for them. Rock was becoming funky for a while. And it worked!

“A lot of people said that [Queen’s 1982 album] Hot Space didn’t work, but it actually did. It brought people to a new place. And it gave birth to Michael Jackson doing his incredible stuff – and later, Michael Jackson inviting Slash to play on a track with him. All that sort of stuff. It was that fusion of funk and rock which I think lives with us to this day.“

Chris was Editor of Total Guitar magazine from 2020 until its closure in 2024, when he became Lesson Editor for Guitar World, MusicRadar and Guitar Player. Prior to taking over as Editor, he helmed Total Guitar's world-class tab and tuition section for 12 years, helping thousands of guitarists learn how to play the instrument. A former guitar teacher, Chris trained at the Academy of Contemporary Music (ACM) in Guildford, UK, and held a degree in Philosophy & Popular Music. During his career, Chris interviewed guitar legends including Brian May and Jimmy Page, while championing new artists such as Yungblud and Nova Twins. Chris was diagnosed with Stage 4 cancer in April 2024 and died in May 2025.

![Queen - Another One Bites the Dust (Live @ Wembley 1986) [HD] - YouTube](https://img.youtube.com/vi/HnCgN4knr0Y/maxresdefault.jpg)

![Flash Gordon | Official Trailer [4K] - YouTube](https://img.youtube.com/vi/O6uOHnxf85g/maxresdefault.jpg)

![10. Dragon Attack - Queen Live in Montreal 1981 [1080p HD Blu-Ray Mux] - YouTube](https://img.youtube.com/vi/_gAhvNCGK0s/maxresdefault.jpg)