All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

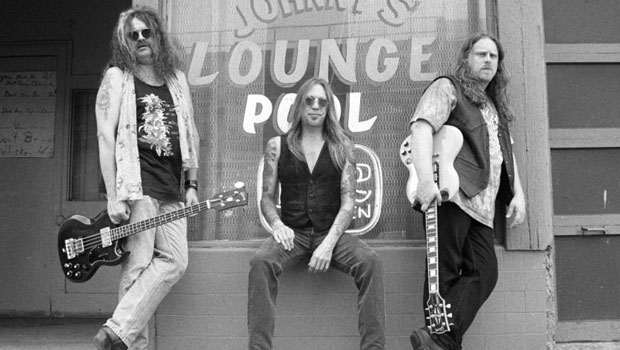

Gov’t Mule recently released the first installment in their Bootleg Series. The Georgia Bootleg Box is a six-disc set capturing a three-night run from Georgia in 1996.

The band was recorded live at The Georgia Theater in Athens on April 11, The Roxy in Atlanta on April 12 and Elizabeth Reed Music Hall in Macon on April 13.

The box features the band's original trio of Warren Haynes, Matt Abts and the late Allen Woody, with guest appearances by a young Derek Trucks and Tinsley Ellis.

You can hear the April 11 version of ”Blind Man In The Dark” here.

I caught up with Haynes to discuss the new release, which is on Evil Teen Records.

GUITAR WORLD: Why did you choose these particular shows to release?

I just really liked the way they were captured and thought they offered a great snapshot of where the band was at that time. I thought Woody was playing his ass off and the whole band was playing great. It was us after about a year and a half of being together, so we were cohesive but still very hungry and trying to prove a point. We were still growing every week, adding songs to the repertoire, writing new songs, rehearsing them at soundcheck and then playing them that night.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

A lot of the rehearsals took place in Georgia, in the old Capricorn studios, at the Big House, which was then the home of Kirk and Kirsten West. So, though we didn't live in the state, it played a big role in our birth and development.

You and Woody were still in the Allman Brothers, which you would you leave in another year to focus on the Mule. Were you starting to think of this as something more than a side project?

Yes. We didn’t look at it as something that was going to go on year after year and continue to make records, but we had made the decision to at least make an effort to really take it somewhere. It wasn’t just about playing fun gigs. Now it’s been 17 years!

In the beginning the audiences were small, the ticket prices were low and we weren’t putting ourselves under any pressure. There was a looseness that comes from that. On the other hand, we had a lot to prove because in the beginning a lot of the crowd were curious Allman Brothers fans who wanted to see what me and Woody were up to and they were often surprised that we sounded so different. My explanation was always, “Why would we start a side project that sounds just like the band we’re in?” That never made sense to me.

Obviously, you want the people who are there to enjoy the experience as much as possible, but they usually stood with us and once they realized how much fun we were having, they were along for the ride.

Did the security of the Brothers gig allow you guys to take more chances in the Mule?

Yes, I think so. We were just creating the parameters of what the Mule was, which didn’t exist yet. There wasn’t the pressure of Gov't Mule being our only source of income or only source of musical creativity, but it was definitely what we were digging the most. We were a band of brothers. We were best friends and we were getting closer and closer and tighter and tighter. It was a really magical period for the band and for the music. We were playing together almost every night, we were getting to know each other personally and professionally quite well, and it was just a lot of fun.

Does digging into your past this deeply impact your thoughts on the current band at all?

Any time I listen to any of the old stuff, it’s always inspiring and inspires me to want to revisit some of the directions we were traveling. It’s more of a mindset thing. In the beginning, one of the things I loved about the band is the tempos were really slow. We all got into this mode where we loved that the band could play way back behind the groove and keep it so nice and heavy. There’s an art to that and a lot of bands get on the road and start speeding up the tempos, and when you listen to the recordings, they’re not as good for that reason.

I remember [Deep Purple bassist] Roger Glover talking about the word “heavy” on the Rising Low DVD. He thought that everyone misuses it and it’s not about volume, it’s not even the power of what you’re playing; he said it was the way the band fits together and the tempos that make it heavy. We were heavy.

Looking back and seeing how many songs we repeated reminded me that not only was our repertoire relatively small, but we hadn’t completely grasped the concept of doing a different show every night. We were shaking it up, but not to anything like the extent we would down the road.

As you are learning the repertoire, don’t you need to play songs over and over anyhow?

At the beginning, the more you play the songs the tighter they get. The only disadvantage to playing a different show every night is if a song really needs some work, you may not play it often enough, so the tightening doesn’t happen as quickly. But that downside pales in comparison to the upside – keeping yourself and the audience fresh and on your toes. And once you’ve worked up a song and are playing well, it always benefits from having some space to breathe in between performances.

Derek Trucks opened two of these shows with you and played with you. It’s so interesting to hear you working together then, now that you have such a deep, established musical relationship.

Listening to this stuff from '96, it’s so obvious that he was really cool then. These particular collaborations sound great to me and remind how much fun it’s always been to play with Derek. He was fearless from the beginning. We would say, “We’re gonna do x y or z in this key” and he would nod and say, “OK” and away we went.

You and Woody played together in the Allman Brothers for about seven years before forming Gov’t Mule. Did you develop a close relationship right away?

Yes we did, and by the time we formed the Mule that had really solidified. I had a solo band on the side for a while and we released Tales of Ordinary Madness in 1993. I enjoyed a lot about that experience and the shows we did, but I had come to the conclusion that I really didn’t want to be a solo artist. I wanted to be in a band. I’m comfortable calling the songs, I’m comfortable singing most of the songs, I’m comfortable being a leader but I didn’t want it to be all about me with hired guns. That just didn’t work for me in the same way. At the same time I was realizing that, Woody approached me and said, “Hey, why don’t we do something together?” So it all just clicked.

Check out Alan Paul's new Amazon Ebook, One Way Out: An Oral History of the Allman Brothers Band (Kindle Single), which is available now at Amazon.com.

Photo: Kirk West, kirkwestphotography.com

Alan Paul is the author of four books, including Brothers and Sisters: The Allman Brothers Band and the Inside Story of the Album That Defined '70s as well as Texas Flood: The Inside Story of Stevie Ray Vaughan and One Way Out: The Inside Story of the Allman Brothers Band – both of which were both New York Times bestsellers – and Big in China: My Unlikely Adventures Raising a Family, Playing the Blues and Becoming a Star in Beijing, a memoir about raising a family in Beijing and forming a Chinese blues band that toured the nation. He’s been associated with Guitar World for 30 years, serving as managing editor from 1991 to 1996. He plays in two bands: Big in China and Friends of the Brothers (with Guitar World’s Andy Aledort).