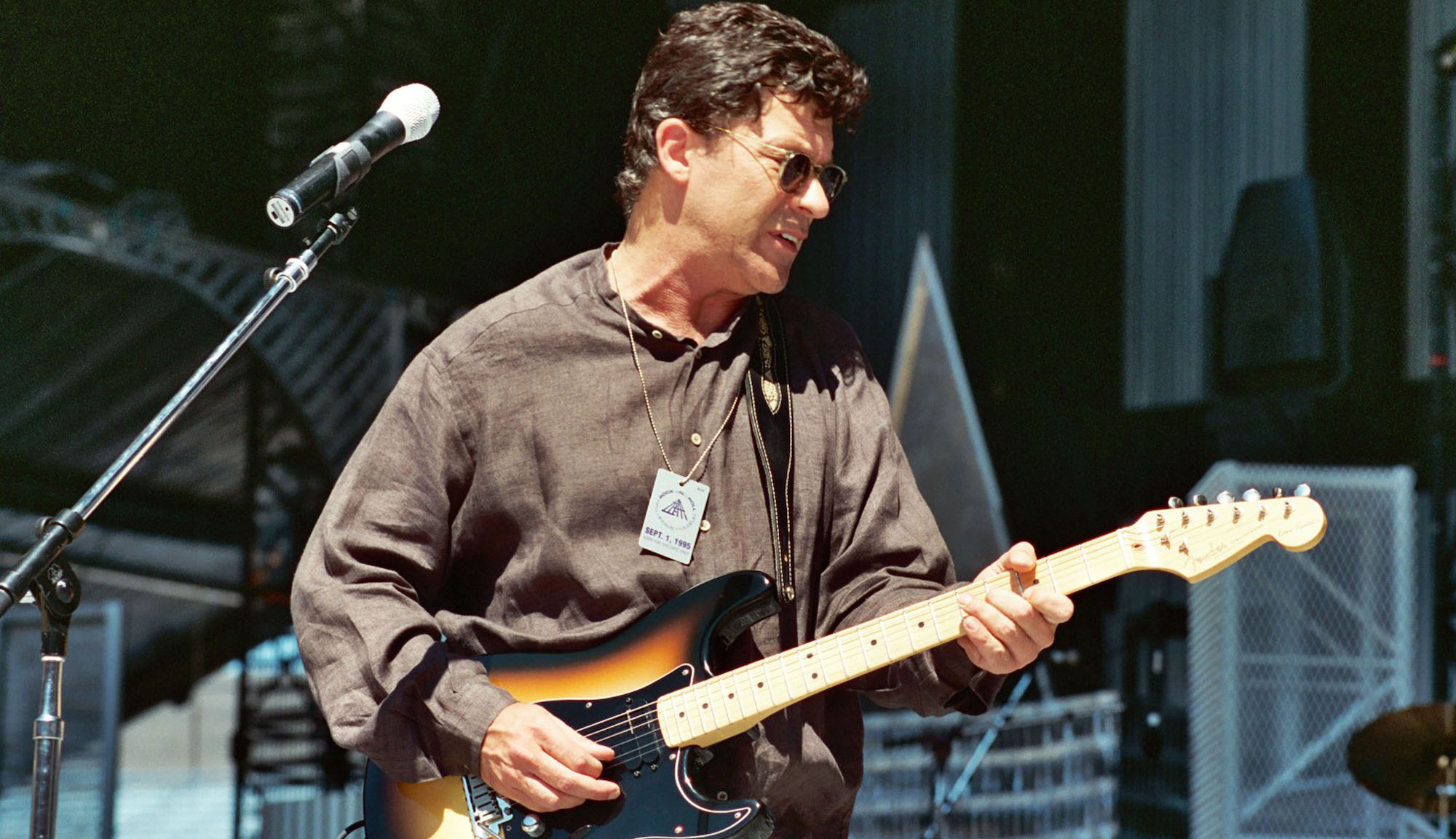

Robbie Robertson, guitarist for Bob Dylan, the Band, dies at 80

The famed guitarist had recently completed work on the score for the upcoming Martin Scorsese film, Killers of the Flower Moon

Robbie Robertson, a skilled guitarist best known for his work with Bob Dylan and the Band, has died at the age of 80, Variety reports.

Robertson died today (August 9) after a battle with an unspecified illness, the guitarist's management said.

“Robbie was surrounded by his family at the time of his death, including his wife, Janet, his ex-wife, Dominique, her partner Nicholas, and his children Alexandra, Sebastian, Delphine, and Delphine’s partner Kenny,“ Robertson's longtime manager, Jared Levine, said in a statement obtained by Variety.

“He is also survived by his grandchildren Angelica, Donovan, Dominic, Gabriel, and Seraphina. Robertson recently completed his fourteenth film music project with frequent collaborator Martin Scorsese, Killers of the Flower Moon. In lieu of flowers, the family has asked that donations be made to the Six Nations of the Grand River to support the building of their new cultural center.”

As the guitar-slinger for The Band – who backed Bob Dylan on some of his most influential work, before embarking on a remarkable career of their own – Robbie Robertson left an indelible mark on rock guitar, and had a major role in shaping the sound of the 'Americana' genre (even though he himself was Canadian).

Born in 1943, Robertson was raised in Toronto, and was swept up by the mid-Fifties rock 'n' roll craze. By his teens, Robertson had picked up the guitar, and began cutting his teeth with a variety of bands, one of which came to the attention of rockabilly star Ronnie Hawkins.

Hawkins took the young Robertson under his wing, incorporated him into his backing band, and even recorded two of the young guitarist's songs. By 1961, Hawkins' band – dubbed the Hawks – had come to include, in addition to Robertson, drummer Levon Helm, and multi-instrumentalists Rick Danko, Garth Hudson, and Richard Manuel.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

As the years went by, though, the Hawks began to tire of Hawkins' tight-fisted leadership, and – wanting to develop their own material – set out on their own.

In the midst of their own touring commitments in 1965, the group came into contact with Bob Dylan, who was looking for a backing band for what would become the singer's infamous 'electric' tour. It was Robertson who suggested Dylan hire Helm as a drummer, after which the two convinced Dylan to take the rest of the Hawks on as a full backing band.

It was the Hawks – sans Helm – who backed Dylan during one of the most infamous gigs of his career, at the Manchester Free Trade Hall on May 17, 1966. So offended by Dylan's move toward rock music, an audience member shouted “Judas!“ at the singer during a break between songs, after which Dylan told the Hawks to play the next song (Like a Rolling Stone) “fucking loud.“

Despite the at-times hostile reception of his first venture into rock, Dylan kept the group (which would soon become known simply as The Band) on, working on copious amounts of new material with the group in a remote house that came to be called “Big Pink.”

The music the Band hashed out in that location with Dylan would shape both the latter's subsequent work, and their own, for years to come. The Band would even name their 1968 debut album, Music From Big Pink, after the house.

Music From Big Pink was musically distinct, and contained a number of classic songs – among them the group's moving take on Dylan's I Shall Be Released, and Robertson's The Weight, which would be immortalized in the classic counterculture film, Easy Rider.

The Band's self-titled, 1969 sophomore LP further raised their profile, and contained more Robertson classics, such as Up on Cripple Creek and the epic The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down. By 1970, the group had graced the cover of Time magazine, and featured prominently at the Woodstock festival the previous year.

As the '70s wore on, though, The Band – despite their enormous commercial success and even a prominent stage and studio reunion with Dylan in the middle of the decade – began to fracture, with the rest of the group (Helm especially) chafing at Robertson's dominance.

In 1976, The Band – weary of constant touring – decided to call it quits with an epic concert they called The Last Waltz. Packed to the brim with the group's superstar friends, it was captured for posterity by Martin Scorsese, and went on to become one of the most famous rock concert films of all time.

Robertson never re-joined The Band after they reunited the following decade, and would release a number of well-received solo albums, the last of which was 2019's Sinematic.

His most prominent post-Band work, though, would come with Scorsese, with whom he worked on over a dozen film soundtracks, works that showed the true breadth and scope of Robertson's musical talent and knowledge.

“I came in on a rock 'n' roll train, blues and country music mixed together where the music played a part of it,” Robertson once said of his musical approach.

“There was a sound, there was an effect to this whole thing and it all added up. That's what made rock 'n' roll to me. You mix this and you mix that and a little bit of this and a little bit of that and you get something and God knows what it is. It's just magical when you put it all together.”

Jackson is an Associate Editor at GuitarWorld.com. He’s been writing and editing stories about new gear, technique and guitar-driven music both old and new since 2014, and has also written extensively on the same topics for Guitar Player. Elsewhere, his album reviews and essays have appeared in Louder and Unrecorded. Though open to music of all kinds, his greatest love has always been indie, and everything that falls under its massive umbrella. To that end, you can find him on Twitter crowing about whatever great new guitar band you need to drop everything to hear right now.

![B.B. King [left] cups his hands to his ear as he asks the crowd for more. Joe Bonamassa, with a Les Paul, gives his crowd a thumbs up](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/P3XrQLh86C27JfPp4AGp6n.jpg)