“They kept talking about this bizarre guitar player who practiced nonstop in his room and was very eccentric. I thought, ‘I want to work with him’”: Bill Laswell survived Buckethead, John Lydon, Ginger Baker and Eddie Hazel – and made it sound easy

The bass journeyman, soundscape creator and producer recalls having his P-Bass stolen the night before his first Brian Eno session, making PiL classic Rise, and hoping illness hasn’t ended his surprisingly fight-free career

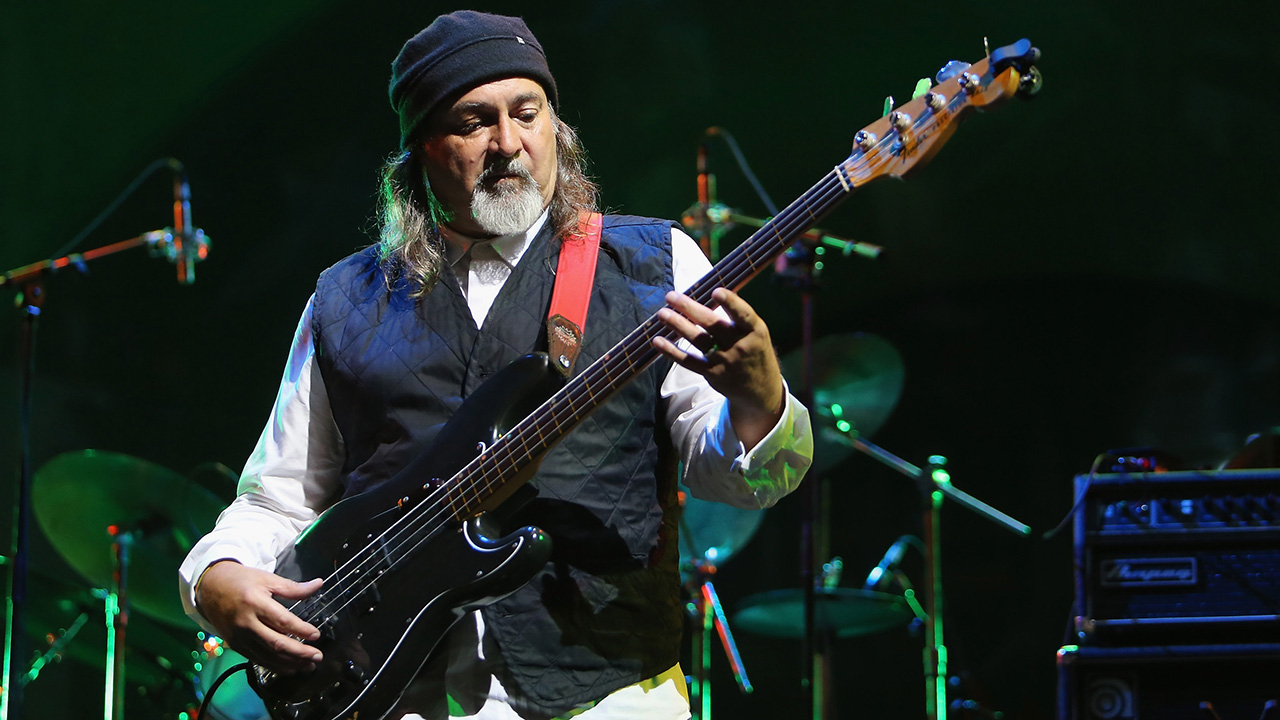

Bill Laswell isn’t so much a bass player as a creator of low-end worlds, having crafted soundscapes for Brian Eno, John Lydon, Ginger Baker, Eddie Hazel and Buckethead. “You just get an idea, try to execute it, and see if it works for them,” Laswell says.

His approach to records such as Eno’s My Life in the Bush of Ghosts, PiL’s Album and Last Exit’s Iron Path is simply explained: “I made decisions to try different things. Most people who get that far into the game just keep going, which can be profitable.

“But I’m glad I went in another direction – people that I considered to be great musicians started to call.”

In recent years, the 70-year-old has been slowed by health issues. While he’s currently not working he has hope for the future.

What initially drew you to the bass?

“Being in bands was the cool thing to do. Most bands had a guitar player and a drummer; I realized what was missing, and what was the easiest thing to fit into playing with people, was a bass. It was to do with availability – if you can get that instrument, they’ll need one.”

Your approach lends itself to soundscapes rather than simply supporting the rhythm. What drew you to that?

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“In the mid-’70s there were a couple of Eno records I liked. He happened to live down the street from me in Manhattan. I kept bugging him to get gigs and play on stuff. He’s open to trying new things, and if something feels okay he’ll consider moving in that direction.”

What gear did you use on Eno’s My Life in the Bush of Ghosts?

“On Bush of Ghosts I had a Fender fretless Precision Bass, which I was really happy with. The night before recording I played at CBGB’s, and when we finished we loaded the stuff into an open truck. Somebody grabbed the bass I had sticking up out of the truck. It was gone.

“I had the session next day around noon. I went to the studio on 12th Street and said, ‘I have no bass.’ Then I made a call to a guy in Queens and he showed up with a bass – which was terrible! I don’t even know what make it was, but it had a big sticker on the front that said ‘Devo.’”

How did it work out?

“We made the best of it. Later on, I found the bass that was stolen in a store. I bought it back for much more than it was worth. But I did get it back!”

What was your approach to Eno’s Ambient 4: On Land?

“With On Land, I wasn’t really bass playing; it was more making sounds with different things in the studio, then putting on effects.”

How did you end up working with Herbie Hancock on 1983’s Future Shock?

“Herbie’s manager, Tony Meilandt, was pretty animated and energetic. He’d just discovered drugs. He came around to a punk club where I was playing and asked if I wanted to do something – and of course, I was interested in Herbie. I wasn’t thinking too much; I just went with what I was surrounded with, which was the beginning of hip-hop.”

You hooked up with Afrika Bambaataa not long after.

“With Bambaataa and people like that, you don’t think about instruments too much. If you can find an idea that works with what they’re trying to do, you go with that. You don’t say, ‘I need this bass or this amp’ – it’s not that way with DJs, Bambaataa or even Herbie.”

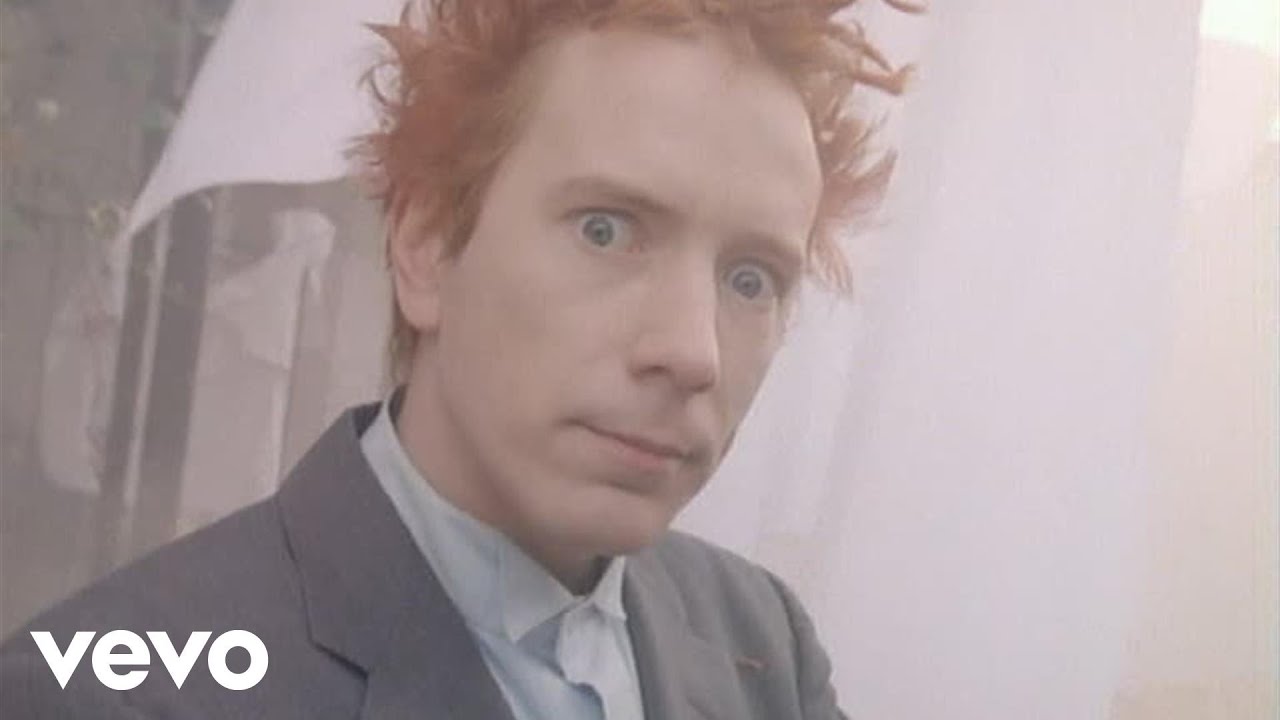

In 1986 you played on PiL’s Album. What was John Lydon like?

“John came around because I’d worked with Bambaataa on World Destruction. I liked PiL a lot, but Lydon was not easy, as you can imagine. From time to time he’s actually pretty shy; kind of sensitive. So, step-by-step, we put it together.

“I realized early on that I’d do the record, but I don’t really value the musicians he was working with at first. So I started to build tracks with the people I was meeting at the time. I decided to take a chance and go for it, and it worked out. It wasn’t fun for John, I don’t think – but we did something okay!”

Can you remember putting the track Rise together?

“I did it in my house with guitarist Nicky Skopelitis. Then we went to the Power Station studio where Jason Corsaro was engineering. I cut it with [drummer] Tony Williams. That first take is the one that’s on the record.

“But I made a mistake on it – there’s like a half-step wrong note, and I said, ‘No, keep that. I don’t want to change the first-take concept.’ So every time somebody overdubbed it I said, ‘Right there, it’s a little different!’”

Ginger Baker didn’t really argue. I’m the guy who was paying him, so we got along!

You started working with Ginger Baker in 1986. That must have been a trip.

“The Ginger thing came up during the PiL record. John was always half-joking, ‘I want to get Ginger Baker as the drummer.’ I said, ‘That’s actually a great idea!’ But nobody knew how to get to him.

“We put the word out, and he was in the north of Italy, living on a farm on a mountain with no electricity and very little communication. I went to Italy and explained the situation. He liked the idea. I think he wanted to get out there and play.

“So he came to New York, and I was the producer – the boss of the record or whatever. We didn’t really argue. I’m the guy who was paying him so we got along, you could say! And from that I said, ‘Let’s keep doing things.’

“I recorded as much as we could with Ginger, just to get him back to playing again. I think he enjoyed it. But he could be a little difficult with people. If you’re taking heroin, speedballs and cocaine for 30 years, it’ll make you a little cranky! When he was up it was a lot of fun; but when you crash on that stuff, it can be tough on people.”

Also in 1986, you formed the genreless Last Exit with Sonny Sharrock, Peter Brotzmann and Ronald Shannon Jackson.

“That came about because there was an offer to do a tour. I’d been working with Ronald, so I went to him first. Then I asked Sonny, who I’d always wanted to do something with. I’d just met Peter, and he was fun, and heavy drinking at the time!

“We went to Europe, and even more than musically, we just liked each other. It was fun, even though the money could have been better. But the music was pretty destructive. We didn’t understand right away that it was going to shock people – but I guess it made a statement.”

Between 1989 and 1995, as part of your Axiom project, you collaborated with several members of Parliament-Funkadelic on Funkcronomicon.

“I listened to all of those guys from the beginning. It was good to record them and make sure they got heard by people. It was good to meet everybody, and in some cases, it went on for a long time. I recorded with Bernie Worrell and Bootsy Collins, who were very versatile.”

Funkcronomicon was Eddie Hazel’s last proper recording.

Buckethead wanted to work with Michael Jackson and Bootsy Collins. I said, ‘I don’t have access to Michael, but we can do something with Bootsy’

“Eddie had a lot of technique as a guitarist – but he was also doing a lot of drugs and a lot of drinking. I actually got an advance to do a record with just Eddie, and I paid him upfront.

“I was going to Japan for some reason and I said, ‘I’ll be back in a week. We’ll get an idea and go.’ He was looking forward to it, but now he had a little money, which was a first in a long time.

“So while I was in Japan, he died. I’d thought if we cleaned everything up a little bit, he could have done a lot, you know? But I just couldn’t do everything at once.”

In the mid-’90s you hooked up with Buckethead.

“I met him through a band in San Francisco called Limbo Maniacs. I was working on their record, and they kept talking about this unique, bizarre guitar player, who practices nonstop, plays in his room, and was a very eccentric character – to say the least.

“I thought, ‘I want to meet him and work with him.’ I met him, and he told me the musicians he wanted to work with were Michael Jackson and Bootsy Collins. I said, ‘I don’t have access to Michael Jackson, but we can do something with Bootsy.’

“So I brought Bootsy and him together and everybody had a good time, so we kept doing recordings. And Buckethead got a deal with Sony and did his record. Then in New York, we played live together, which was the last time.”

What’s your outlook on continuing to play and record?

“If I can move forward, it won’t be any different – I’ll just keep recording and trying to encourage other people who have projects. And I’ll try and make sure that I can always have some kind of studio situation.”

- Follow Bill Laswell on Instagram.

Andrew Daly is an iced-coffee-addicted, oddball Telecaster-playing, alfredo pasta-loving journalist from Long Island, NY, who, in addition to being a contributing writer for Guitar World, scribes for Bass Player, Guitar Player, Guitarist, and MusicRadar. Andrew has interviewed favorites like Ace Frehley, Johnny Marr, Vito Bratta, Bruce Kulick, Joe Perry, Brad Whitford, Tom Morello, Rich Robinson, and Paul Stanley, while his all-time favorite (rhythm player), Keith Richards, continues to elude him.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.