“His reaction went from polite puzzlement, to resistance, to anger. He finished up with, ‘I think it's a dumb idea’”: When Anthony Jackson came up with the idea for a six-string bass, he struggled to find anyone to build it

Along with Leo Fender, the late Anthony Jackson became one of the most important figures in the history of the electric bass

Thumb through an assortment of bass guitar books that attempt to include the history of the instrument, and it's alarming how hazy the birth of extended-range bass guitars seems to be, with 5-strings preceding 6-strings, instruments magically and simultaneously emerging from guitar companies in the early '80s, and other such falsehoods.

In truth, the path to today's easily accessed, wide assortment of 5’s and 6’s was forged largely by one musician, the late Anthony Jackson.

A perfectionist with an unshakable commitment to artistry in all settings, Jackson conceived an electric bass with six strings as far back as 1968, leading to his invention of the first ‘contrabass guitar’ in 1974.

“I was 16 and I had been playing bass for about four years,” Jackson told Bass Player in December 2008. “While practicing with a collection of Jimmy Smith organ trio records, I kept finding myself running out of room while walking – wanting to get down underneath the bottom register and wanting to move to the upper register without feeling like I was going to run out of space.

“I had been tuning the instrument down a half- or whole-step since the first band I played in, at age 12. But for whatever reason, at this particular time the idea to put another string on the bottom occurred to me, and I thought, ‘While we're at it, let's put a string on top and extend the range in both directions.’

“Being so young, I had no idea of the problems building such an instrument would impose, but I was determined to get it built.”

Jackson’s road ahead was paved with detours in the form of reluctant builders, closed-minded producers, and countless trial-and-error design dead ends.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

While his dogged pursuit of his dream instrument helped fulfil his musical voice, the process also led to the standardisation of extended-range basses worldwide.

“In the fall of 1982, I took a big chance and retired my Fender, choosing to use only my contrabass guitar. For the most part, I didn't have any problems because I had already established a reputation as a serious and respected bass guitarist. Still, some were uneasy when I pulled out the 6-string in the studio.

“One of the most negative comments got back to me second-hand: ‘You tell Anthony Jackson if he wants to bring his science experiment, then let him book his own sessions. I want to see the Fender!’”

A true bass scholar, Jackson went on to play on seminal pop and jazz recordings with the likes of Billy Paul, the O'Jays (that's Jackson's picked groove on For the Love of Money), Chaka Khan, Steely Dan, Paul Simon, Al DiMeola, Steve Khan's Eyewitness, Michel Camilo, and Wayne Krantz.

What are the details of your collaboration with luthier Carl Thompson?

“I asked Carl Thompson to build me a bass in 1974. His reaction went from initial polite puzzlement, to resistance, to anger. He didn't see the purpose in the low B; he felt no one would be able to hear it, as the speakers in cars and television sets were too small. I told him I was certain it would work.

“He asked me to wait while he thought about it, and finally, he came out of his workshop and said, ‘I'll do it, but here are the conditions: I'm not going to help you, you're going to have to tell me exactly what you want done. If it doesn't work it'll be your fault, and if it does work, you take the credit; I don't want my name associated with it. And I'm going to charge you $2,000 for my time.’

“I remember thinking, ‘What am I getting into here?’ That's an awful lot when a new Fender cost $350. He finished up with, ‘I think it's a dumb idea.’ But I was enough of a dreamer and a fool in the eyes of some to agree to his terms.”

Where did you use the Thompson and what was the reaction?

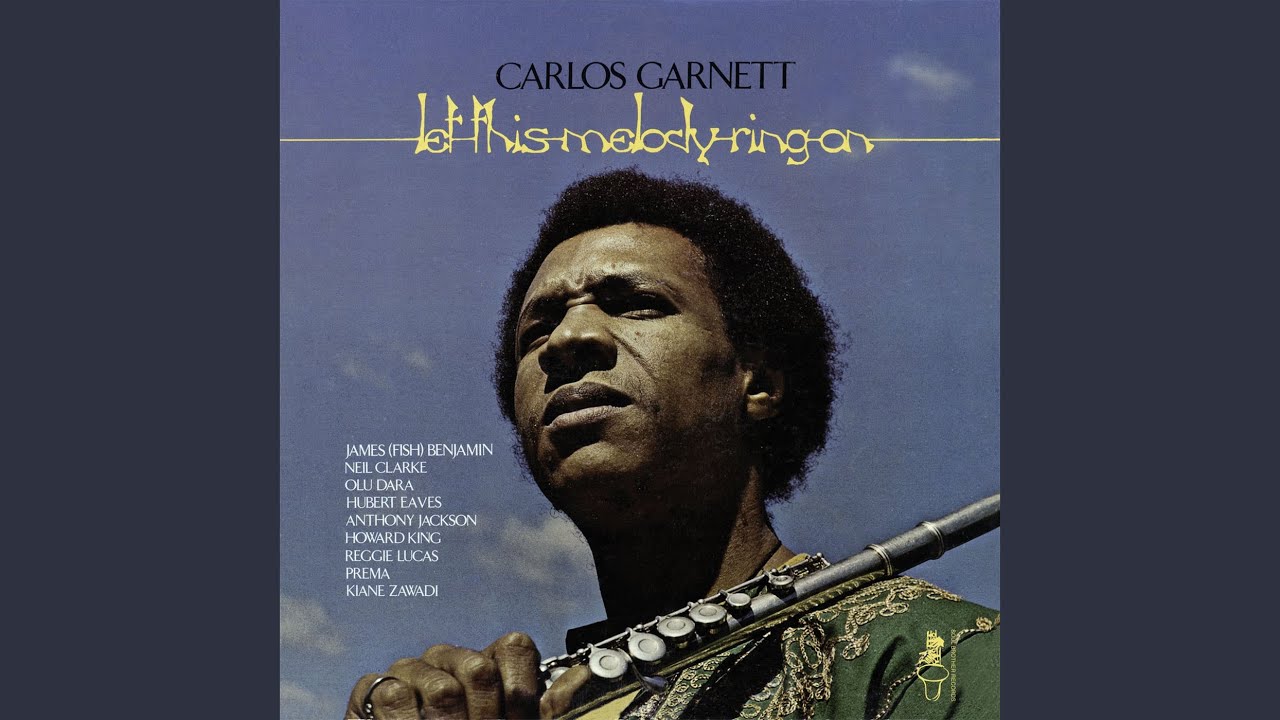

“I brought it to one recording session, playing it on the title track of Carlos Garnett's album Let This Melody Ring. I remember no exaggerated reaction from either the musicians or those behind the glass. I also took it on one tour with Roberta Flack, playing it on a few songs where I wanted to get down lower.

“No-one gave me a hard time, and the instrument sounded pretty good in both cases. I knew by then I wasn't going to stay with it, though; I would use it mainly to gel practice on the two new strings and to get comfortable reaching in-between what was now a maze of strings.”

What was your initial reaction to having six strings?

“Basically, I felt like the concept had worked. I focused on exploring the low B initially, and being conscious of not overusing it. Of course, l explored chordal playing, but my primary goal was not to become a great jazz soloist. My vision for the contrabass guitar was as more of a concert instrument with extended range, to be able to play orchestral parts previously not possible.

“If you watch the YouTube clip of Streetwise, from Simon Phillips's instructional DVD, you’ll see me playing the original melody at pitch, at the very top of the instrument, at the end of the clip.”

“A couple of principles come through there: I'm sitting down and raising the instrument on my right thigh, pointing the neck upward, leaning close in, and using a pick. It would be impossible to play this passage standing or sitting with a strap on because the instrument can't be swung that far. That's the kind of potential I had in mind when I say I envisioned it as a concert instrument.”

Meanwhile, your lack of a contrabass guitar didn't halt your exploration of extended low range on many of your “career” recordings.

“Correct. In 1978, I started doing really intensive down-tunings of a major 3rd or a 4th on my Fender Jazz the night before a session, using epoxy cement and serrated kitchen knives to raise and file the nut, while also adjusting the truss rod and bridge. I'd tune down all four strings so they had an even feel and tone across the neck.

“To get the notes I wanted, I had to play with the lightest touch possible. It was a priceless education on controlling my instrument with my fingers only, learning how to make them speak and dance – from an almost subliminal whisper to a roar, all without plucking too hard, which would have caused the strings to hit the fingerboard and go sharp.

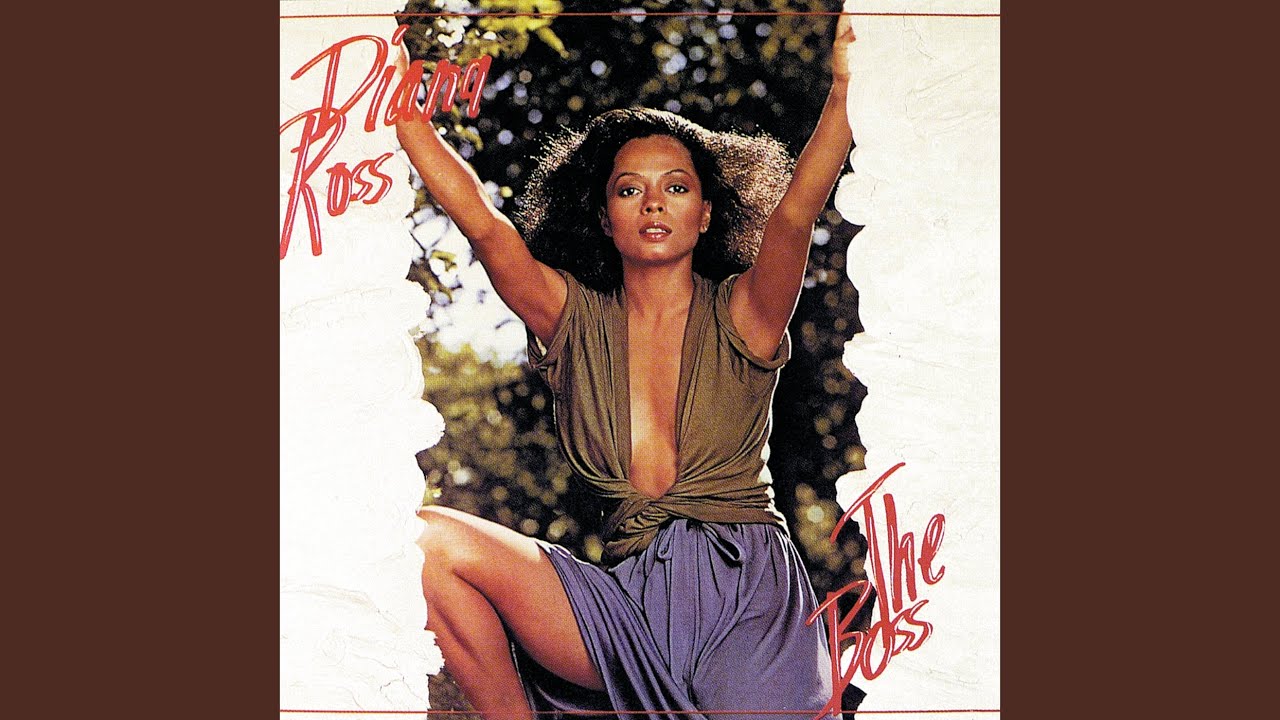

“One of the first tracks I cut this way was a Diana Ross song called No One Gets the Prize, from her album The Boss. Another early attempt was the chorus of Chaka Khan's Love Has Fallen on Me, from her album Chaka. That paved the way for the more widely known down-tunings I did on Chaka's albums Naughty and What Cha' Gonna Do for Me, and the Luther Vandross cover of A House Is Not a Home, from his album Never Too Much.”

How did you come to work with Ken Smith on your next contrabass guitar?

“My career pace necessitated an almost four-year void in my next attempt. While working on pianist Warren Bernhardt's album Manhattan Update, I happened to use Ken's original 4-string on two tracks, and it worked well. I approached Ken about building my instrument, and he was quite reluctant at first.

“I finally convinced him, but he felt the Fender spacing I wanted would result in a neck that was too wide and difficult to play; he insisted on a little closer spacing, to which I relented. I got the instrument in December 1981 and it was just comfortable and playable enough for me to stay with for a year and a half. Ken indeed widened the spacing when he began making them in production.

“The other problem I discovered with the first Smith was it couldn't be used with a pick; the sound was dull and thick. I used it on the tour for Al DiMeola's Tour de Force: Live album, with Steve Gadd, Jan Hammer, and Mingo Lewis, and the whole time Al complained he wasn't hearing my usual top-end.”

“I finally relented and plugged in the Fender, which I had with me, and everyone's jaws dropped! Jan said, ‘There it is – there's your sound!’ So although the Smith is pictured somewhere in the album, I replaced all my parts in the studio later, with the Fender.

“The second Smith came in early 1984, which was the last 34"-scale prototype; the spacing was right and the sound was improved. I recall it working very well on a track from George Benson's 20/20 album, called New Day, as well as Michel Camilo's album Suntan.”

With Fodera, you seemed to find the perfect partnership.

“Without a doubt. They were working for Ken Smith and when they decided to leave to start their own company, we made a barter arrangement: they would build me whatever instrument I wanted; I would try it out both in studio and onstage, and give them feedback as to what was and wasn't working; and they would filter these ideas into their production models.”

“Then they would build me another, and the cycle would continue. It's a partnership of three, with Vinnie as the luthier, Joey as an integral go-between, being a professional bassist himself, and me testing the instruments.”

What were the key design changes over the course of your prototypes?

“A key for me was an intuition I had while lying in bed in late 1987 about building a Presentation model that would have only the features I wanted on it: A 36”-scale, extra-wide neck at nut and bridge, 28 frets, no electronics, no controls, a chambered body, and a single pickup.

“One well-placed pickup, I felt, would result in a richer, more complex sound than any two pickups; with two, you've got a lot of audio information obstructed by other audio info that's simply out of phase. Why not choose the best spot to get the most information out of one pickup?”

The most striking alteration was the single cutaway.

“Agreed. In early 1989 I had expressed concern about neck instability. A few weeks later Vinnie said he wanted to try a single cutaway with the horn extending much higher up than normal to grab hold of and stiffen the neck. I remember being miffed; it's going to look clumsy and be too heavy. He assured me he would carve the back of the cutaway for minimal mass increase.”

“Two weeks later, he came in with a full architectural drawing, and I almost fell to the floor! It was so exquisite, I thought, if this works it will be one of the most beautiful guitars ever conceived, an instant classic – and I still feel that way.”

How has your style and approach changed this many years into playing the contrabass guitar?

“For one, I've come to play with a lighter touch; I haven't had to replace my frets in 13 years. Musically, it's not so much a change of style as it is growth, which is inevitable when you have more range.

“For example, whatever I'd learned from studying Jamerson on the 4-string I could apply in other registers, particularly lower down. There's also a great deal of conceptual freedom for having the range. I enjoy playing with a large ensemble and being the one to put a big, fat foundation under it, like a section of string basses with extensions, or a pipe organ – I could do that alone.

“Or to be able to play very high parts fluidly, without sounding like I was straining. It's a register for the sake of the music, not as a gimmick, or to play more notes, or to make other bassists go, ‘Wow!’

“It's like having a car with a larger engine. It doesn't mean you're going to go fast all the time, but high speeds are less of a strain on both engine and driver.”

Chris Jisi was Contributing Editor, Senior Contributing Editor, and Editor In Chief on Bass Player 1989-2018. He is the author of Brave New Bass, a compilation of interviews with bass players like Marcus Miller, Flea, Will Lee, Tony Levin, Jeff Berlin, Les Claypool and more, and The Fretless Bass, with insight from over 25 masters including Tony Levin, Marcus Miller, Gary Willis, Richard Bona, Jimmy Haslip, and Percy Jones.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.